Our knowledge of any contact between David Smith and Martha Graham is limited – based largely on sketches that Smith made in the late 1930s or early 1940s, which in turn were based on photographs by Barbara Morgan of Graham performing her solos Lamentation and Frontier. In addition there is what Smith’s first wife, Dorothy Dehner, told Candida Smith, one of the sculptor’s two daughters from his second marriage. The private papers of Graham and Dehner, both still sealed, may eventually yield more information.

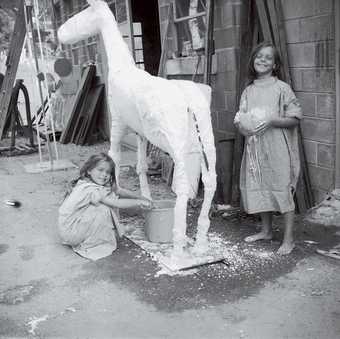

We also have proof of Smith’s interest in modern dance (ballet he found artificial) in several small works, such as the abstract Dancer 1935, and the more figurative pieces At the Bar 1941 and Boaz Dancing School 1945. Franziska Boas, the daughter of anthropologist Franz Boas, a dancer-choreographer, writer, teacher and the creator of a percussion orchestra, taught summer courses in Bolton Landing, New York, where Smith and Dehner bought property in 1929. The little floating eyes in Boaz Dancing School represent the interested citizens to whom she opened her studio every Wednesday and Friday evening. She and Smith may well have been kindred spirits; before taking up dancing, she had studied sculpture quite extensively.

What must have drawn Smith to Graham were the forceful lines and counter tensions that her body imprinted on space. It’s interesting to consider that when she was searching for new ways to present the female form on stage, one of her sources may have been sculpture. According to dancers who worked in her company during the late 1920s and early 1930s, she was very much drawn to the works of Ernst Barlach. Lamentation has something in common with Barlach’s Russian Beggar Woman 1907. His figure sits on the ground; the only parts of her not covered by a bronze sweep of fabric are her hands – one bracing her hooded, bent-over body, the other reaching out, cupped. Graham’s mourning woman, seated on a bench, presses against the elastic sheath of fabric that confines her, concealing everything but her face, hands, feet and a bit of her chest.

It seems likely that Dehner, who studied with Graham, took Smith to see Graham’s dances in the late 1920s, when the choreographer had already turned away from the Orientalist genre pieces of her mentors, Ruth St Denis and Ted Shawn, towards a physical vocabulary and Modernist art, architecture and industrial design. By 1928 she had made the pieces Immigrant and the anti-war Poems of 1917. In 1929 she formed a company of around a dozen women and taught them exercises that shaped them into the kind of dancers she needed for her work. The bodies she created had the tensile strength and powerful clarity of moulded metal. Angular, thrusting, playing sharp lines against curves, the movements of her women formed images of struggle and triumph; their faces, like those of Smith’s abstract personages, were mask-like, rendered expressive by the gesture of the entire body. The form-fitting dresses of stretch jersey that Graham’s company members wore in the earliest works emphasised their torsos, inhibited their legs from any displays of balletic expertise and rendered them most significantly as elements of a passionate architecture. Interestingly, in Smith’s renderings of the Morgan photographs (collected in Morgan’s 1941 book Sixteen Dances in Photographs), he lightly traces the lines of Graham’s body as he imagines them under the fabric they animate – the armature beneath the shell.

Even if I had seen only the photographs of Smith at work, I’d have guessed that he had an eye and a feel for motion. You can sense this in Dan Budnick’s images of the sculptor bracing himself to push against one of the massive stainless steel Cubi series of the 1960s, or spreading his arms to grasp Volton XVIII’s opposite sides, crouching on the floor to wield an acetylene torch. Even with assistants, he must have had the physical power and endurance of an athlete to have produced during 30 days in 1962 in Voltri, Italy, not just the two works he had been commissioned to create for the fourth Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto, but 27. The word ‘create’ scarcely suffices; he wrestled the Voltri series into existence.

The artistic kinship between Graham and Smith is reflected in their words as well their works. In 1947, Smith noted his feelings about iron and steel as materials:’The metal itself possesses little art history. What associations it possesses are those of this century: power, structure, movement, progress, suspension, destruction, brutality.’ Almost twenty years previously, Graham had written: ‘Virile gestures are evocative of the only true beauty. Ugliness may be actually beautiful if it cries out with the voice of power.’

Like Graham’s choreography, Smith’s sculptures affirm gravity, yet also strain against or fly away from it. Graham emphasised the challenge of maintaining equilibrium by counter-tension or torque within a fall; Smith created in a stable object the possibility of collapse, the delicacy of balance. Depending on one’s angle of vision, Zig IV, with its curving ‘walls’ and flat ‘floor’, is either doing a nose dive into its small wheeled base, or shooting off into space. Like the narrow silhouettes in Graham’s early works, most of Smith’s series of the 1950s and 1960s, the Forgings, Sentinels and Tanktotems – tall, rail-slender figures – balance on improbably small bases. As with Running Daughter 1956–60 and the stark Lonesome Man 1957, some of these have what can be seen as one slim ‘leg’ curving or angling up behind them.

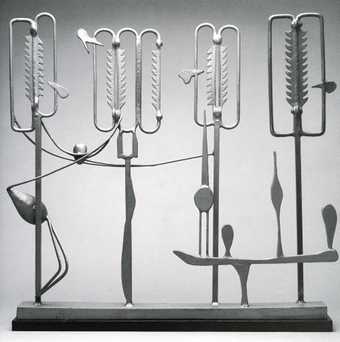

David Smith

Agricola V 1952

Steel

90.2 x 71.1 cm

Private collection © Photograph: David Heald © Estate of David Smith/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2006

Graham’s central movement principle involved a curved-in contraction in the centre of the body followed by an arching release. She likened that action of the torso to a whip handle that impelled the lashing of arms and legs. Although you can often see right through the core of Smith’s sculptures, his centre seems to control, to impel the metal details that fly outward, but never freely.