My sister Candida and I spent the first few years of our lives at Bolton Landing, in upstate New York. We left when I was about four, but would return for two months each summer. It was very lush countryside with fields surrounded by mountains and lots of fruit, vegetables and flowers growing, as well as wild blueberries and apple and cherry trees. My father’s first wife, Dorothy Dehner, described it as ‘a salad bowl’, which was true. It was an idyllic place. We had a pony. There were a couple of little ponds and we had a boat that we used to row around in and go fishing. My father built these play houses for us. One was a real log cabin, another was what he called an African hut, made of an arc structure with straw on it. He would cook a lot – he was really good at preparing Chinese food. That was the thing I liked the best. He would play a lot of music, as well as these wonderful recorded stories – Irish folk tales read by Siobhan McKenna, as well as stories by Lewis Carroll and Aesop. When we went to bed we would fall asleep listening to him playing Bach or jazz. He would be in the back room doing drawings. I especially remember the noise of the spray cans he used to make his spray paintings – you could hear the hissing of the spray, as well as the click-click as he shook the can.

David Smith

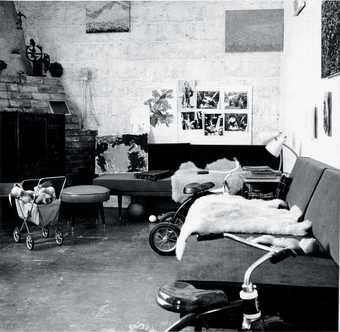

Candida and Rebecca Smith’s bedroom, Bolton Landing c.1962

Photograph: David Smith © Estate of David Smith

He would be in his workshop during the day, and often have assistants there, welding. There were two big rules: we were told not to look at the welding because it was bad for our eyes; and secondly, there was a staircase that went to the roof that we were never supposed to climb without him. I don’t ever remember going into his studio when he wasn’t there. He was always there, unless he was with us. Obviously, it was a dangerous place. You wouldn’t play around with big pieces of metal.

He didn’t particularly talk to us about his work, although I recall him saying: ‘I make sculpture for two girls.’ And he told us about Picasso, and how much he loved Italy and Voltri. In terms of specific works, it is really interesting that Running Daughter 1956–60 looks so much like the photograph he took of me running, but the picture was taken after the sculpture was created. The blur in the photograph was deliberate, I guess, or at least deliberately chosen. The drawing of the sculpture in a sketchbook was called Running Becca. As a parent myself, it reminds me how there are particular things about your children that are special to you; and perhaps me running was one of those things for my father.

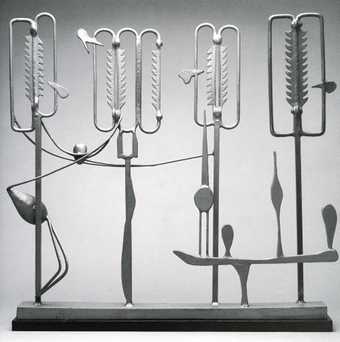

David Smith

Running Daughter, Bolton Landing 1956–60

Painted steel

255.3 x 91.4 x 43.2 cm

Photograph: David Smith

Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York © Estate of David Smith/VAGA, New York & DACS

He had a lot of different aspects to his personality. He was very down-to-earth, but also very cultivated. When we were in Bolton Landing he was friendly, outgoing and comfortable in a small-town situation. But he could get angry really quickly, which was not fun, and kind of scary. He was the sort of person who could talk to anyone. However, I would say he hated phoniness and hypocrisy. He was wonderful with children. He had a lot to give us and had a positive influence on us. We often made things with him. I remember talking to him about my drawings and art. He preferred our abstract works to our realistic pictures and discouraged figuration, which is silly – children want to be able to draw things that look real. He wasn’t very understanding of the little girl stuff: that’s why you have a mother. But the best project we made with him was an amazing life-scale horse. Little girls love horses, and what could be better than making a realistic, life-size horse with your dad? It was a great thing, made of plaster, which was really messy. He welded the armature out of metal and we made the plaster.

Certainly, the fact that my father was an artist validated art making in my eyes as a child. Most adults, especially fathers, are doing something you don’t really know about, because it’s very often out of the home. To have someone doing something where you live, that’s also what kids spend a lot of time doing, is really interesting, because it shows the worlds of adult and child overlapping. And what is it about that grown-up who doesn’t do a regular grown-up thing? I really liked the painted sculptures, because of the colour. That was my strongest opinion as far as his artwork was concerned. I saw him as very different from other grown-ups. Art making wasn’t an official grown-up thing, and sometimes I thought it was really weird.

I always wanted to do something creative when I grew up. At first I thought I would be a writer, but I didn’t enjoy it that much. I got to a point where I needed to be honest with myself, and say: ‘What’s the thing I really like to do?’ So I decided I would be an artist. It was daunting to enter the same area as my father, but I just felt I had to. It was very difficult, and I ignored his work for a long time so I could get a better sense of myself. I know a lot of people whose parents are artists – it’s a struggle. But back in the Renaissance it was like taking on the family business; it wasn’t such a big deal.

- David Smith in the Tate collection