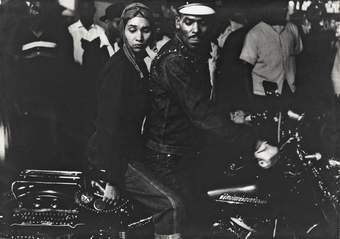

Robert Frank

Indianapolis 1956

Digital image Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala

Over the last decade, I’ve been thinking about the way that images, especially photographic images from magazines, books and television, intersect with our lives. At the same time, it’s dawned on me that certain images have played a central role in my own initiation into the world.

One book we had knocking around the house when I was growing up was The American Image: Photographs from the National Archives, 1860–1960. One shock- ing image it contained was a photograph of an African American man, showing his bare back which was mapped by lashes that had torn his flesh and had now healed, leaving raised scars. His back was a Jackson Pollock painting. It was disquieting and extraordinary, and it has stuck with me ever since.

Don McCullin’s photographs taken in Bangladesh and what was then Biafra had a similarly profoundly impact on how I thought about the world and my place in it. There is one picture of a group of seven very young Biafran kids who look destitute and starved, and each one has a white plaster attached to their forehead. Years later, I discovered that this was a way of marking which of the children, out of all those who were starving, were going to live. Another by McCullin, published on the cover of the 5 September 1971 Sunday Times Magazine, is an extreme close-up of a mother and child during a cholera outbreak in Bangladesh. The child is caught in the throes of absolute mayhem, screaming into the face of their mother, who remains completely calm.

In these harrowing images, someone had found a form for figuring, configuring, reconfiguring the disaster. Some frame was found to make sense of the suffering. I come across this in all the images that I worship and adore.

Not all the images that have become central to me are necessarily grim. The last image in Robert Frank’s extraordinary monograph The Americans comes to mind. It’s of an African American biker couple, taken in the 1950s, sitting on a Harley Davidson. They’ve turned their heads towards Frank, but their eyes are down, almost like a choreographed, operatic refusal to engage with the photographer. One senses this refusal is based on real pride, a self-composure that has been so important in the striving in my own life.

I didn’t so much ‘decide’ to become an artist; it’s more that I was possessed and inhabited by these images in a way that introduced a logic of compulsion into my life. These images instilled in me a desire to make sense of them, to emulate them, and try to see if I could go ‘beyond’ them. They are a series of siren songs that beckoned me, compelling me to voice my entry into the world of image-making.

When I was commissioned to make work for the British Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale this year, these images flooded back. In a way, they have been a threnody in the work I’ve been making over the past 40 years. There is a symmetry to the photographs that have harboured in my life: they have been there from the beginning to the present.

Sir John Akomfrah CBE is the latest artist to represent Great Britain at the Venice Biennale. His work The Unfinished Conversation 2012 was purchased jointly by Tate and the British Council with assistance from the Art Fund in 2014.