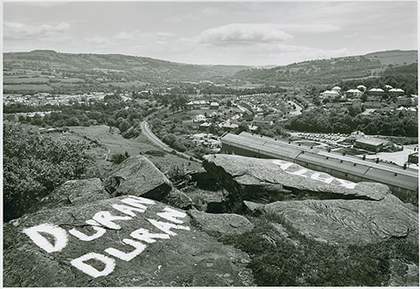

John Davies

Penallta Rocks, Ystrad Mynach, South Wales 1984

© John Davies

It wasn't until 2012, on my first trip to Los Angeles, that I realised my distant childhood memories of the 1980s had been hijacked. As I strolled past faded neon signs and old motels on Sunset Boulevard in the dusk, a red Ferrari zoomed past into the distant subtropical blur, and I had one of the strongest turns of déjà vu I’ve ever experienced. Suddenly it hit me: this West Coast landscape was the 1980s, a narrative encoded in the branding of a decade that had somehow displaced my own experiences of the period when growing up Black and working class in the north of England. It was a reminder that documenting can be used to sublimate and suppress history as well as preserve it; the absences in archives and algorithms are their own type of curation. Even if we were witness to an event or era first-hand, the iconic images of the time can infect our imaginations to the point that our own memories rot into a sort of haunted nostalgia, leaving us pining for a past that never was.

The other danger, of course, is that we imagine a decade lived only in monochrome: black and white, social realist images of billowing chimneys, protests and council estates – those charged, newsworthy moments captured earnestly by documentary photographers during the age of Thatcherism.

But the 1980s was the time when those two worlds collided with each other; the same kid whose parents worked in the mines, who lived in the grey council estate and had posters of Duran Duran or Madonna on their bedroom walls was also exposed to postmodern theory, fashion and art through The Face or i-D magazine. There was also the rise of tourism due to the democratisation of air travel; the dissemination of pop culture on an unprecedented level courtesy of MTV; and the new media of VHS, the Walkman and compact discs.

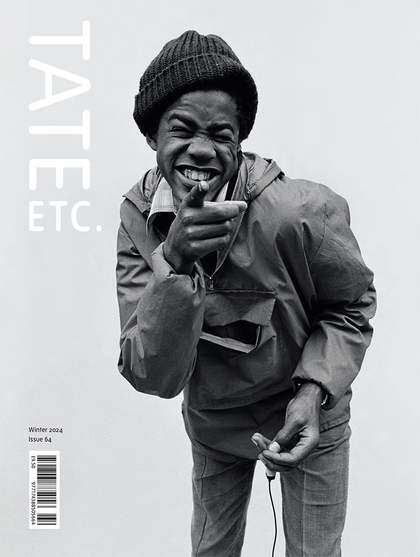

Look more closely at what remains of the 1980s and new messages begin to appear, as is evident by an astonishing new photography exhibition at Tate Britain: The 80s.

Cheyco Leidmann

Foxy Lady EP21 1980

© Cheyco Leidmann

*

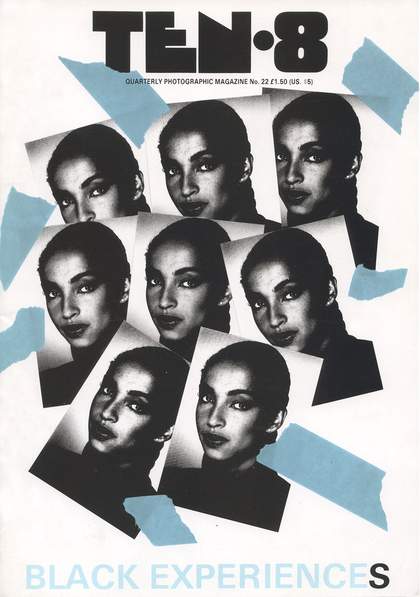

In Britain, investigations into the convergences of such currents fell under the banner of cultural studies, as championed by the late, great writer and activist Stuart Hall. While Hall’s influence permeated any number of media outlets, the best example of his approach as applied to photography is Ten.8 magazine, which Hall patronised. It looms large over the new Tate show. One essay entitled ‘Wearing Your Art on Your Sleeve’ by a young Paul Gilroy is a great example of how new spaces opened up in the 1980s not only for critical thinkers but also for photographic artists. This offered an opportunity for these practices to intersect. In the piece, Gilroy examined the record sleeves of Black musicians as ‘complex cultural artefacts’. By representing the music contained within, these artworks sometimes circumnavigated the mainstream’s more reductive depictions of the Black community. What results is an ‘intricate commodity that fuses different components of Black cultural and political sensibility together in an unstable and unpredictable combination [and] points to a fund of aesthetic and philosophicalfolk knowledge’.

While Gilroy acknowledges the record’s intended ephemerality within consumer society, he argues that the images on the record sleeves had a kind of second life, outside of capitalism, for Black audiences. The artwork held a physical space for powerful, Black cultural motifs and circulated in Black cultural spaces, especially in small, independent record stores, where various covers across genres and the Black Atlantic were jammed together on the walls. Many of the sleeves Gilroy selected to illustrate the piece were from soul, funk and jazz albums from the 1960s and 1970s, a period during which ‘Black political discourse migrated to and colonised the record sleeve as a means towards its expansion and self-development’.

There are proto-afrofuturist covers from the likes of Weldon Irvine, Earth, Wind & Fire, and Parliament-Funkadelic. Social realist photographs of Black, inner-city life appear on the covers from The Impressions and the Philadelphia International All-Stars compilation, and on the sleeves from Jimi Hendrix and early Prince, navigating the ambiguities and ambivalences of Black music, which had a white majority audience.

Front cover of Ten. 8 photography magazine: no. 22, 1986

There is the sense in Gilroy’s piece, though, that by the end of the 1980s, such ‘expansion and self-development’ had been neutered by the rise of neoliberalism and the technological changes that came with it. In the case of the music industry, this took the shape of the compact disc, which reduced the size and scope of these pivotal covers. At a conference in Finland a few years ago, Gilroy told me that he felt there had been a broader ‘war on the imagination’ of my generation born in the 1980s. While I agree with him, despite the huge changes in that decade there were some surprising and counterintuitive ways in which photography, through record sleeves, continued to operate as an unofficial photographic chronicle of the hopes and dreams, not just of the Black community, but of all working-class people. I feel especially passionate about this, because without the photographs within CD artwork I may not have become a photographer.

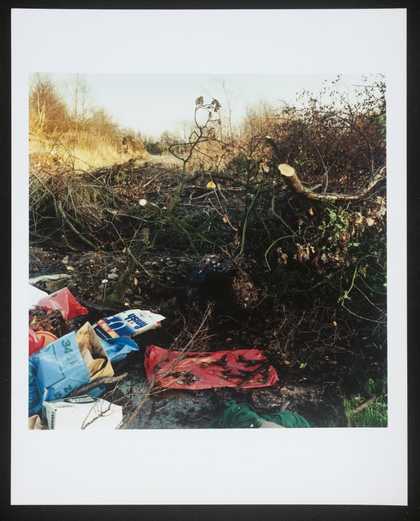

Keith Arnatt

Miss Grace’s Lane (1986–7)

Tate

*

I went to a quintessentially lower-working-class school in Sheffield in the 1990s (to the extent that it was featured in Ken Loach’s anti-Thatcher 1981 film Looks and Smiles). It was as though we were being trained to have low standards and small dreams for the future; to prop up the economy as labourers or die of indifference. I expressed an interest in art, English literature and maths, but my GCSE work experience was at a B&Q warehouse.

‘Don’t get clever’ and ‘stop showing off’ were phrases frequently levelled at us. Upon leaving school I got my first part-time job as a shop assistant at a Debenhams department store, where older members of my family had also found work, having lost jobs in the steel industry. I didn’t last long: sacked for writing poetry on the back of a till roll. I was too ashamed to tell my mom, so would leave home every morning as if I was going to work but instead wander the old industrial hinterlands, eventually working out a specific two-hour route to the city centre, which happened to include some of Sheffield’s last few remaining independent record stores. I would search their bargain bins for CDs that looked interesting, and on one of my listless strolls stumbled across the UK edition of a neo-soul album released in 1998 called Spirit Tales by a Swedish Jamaican singer-songwriter called Stephen Simmonds.

Not only was the music moody and evocative, but the CD inlay booklet contained a series of images of Simmonds in his native Stockholm, his brown skin contrasting against the snow or illuminated by tungsten-lit passageways at twilight. This was around the time kids I’d grown up with in my neighbourhood started getting into serious trouble – one sectioned for a serious attack and later diagnosed with schizophrenia, one jailed for murder, others murdered. I think I was so taken by the Spirit Tales booklet because I saw myself in those photographs – just an alternative version, in horizons expanded beyond my local area. It allowed me to see myself outside of Firth Park, Sheffield and Britain. I didn’t have the word for the experience yet, but what I was feeling would later fall under the notion of ‘Afropean’. I loved the photographs for their plurality; here was a man with my hair and skin colour who looked totally and effortlessly European, making soulful Black music with instruments and sound patches you’d more often find in European chill-out or trip-hop.

Paul Graham

DHSS Emergency Centre, Elephant and Castle, South London, 1984, from the series Beyond Caring 1984

© Paul Graham; courtesy Pace and Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

After finding a film camera in a local store, and inspired by the Spirit Tales CD inlay, I began taking photographs in the same style on my strange, listless wanderings, listening to this soul music from Sweden in my headphones. I still return to the CD inlay, my photographic bible. It contains echoes of what I laterfound in the work of artists such as Paul Graham and Peter Fraser, members of the British new colour movement, when I was set on a trajectory to learn more about the history of photography.

The Japanese philosopher Hiroki Azuma might have described this unwitting encounter between an unemployed working-class teenager and some of Britain’s most important art and documentary photographers as ‘misdelivery’. In his book Philosophy of the Tourist, a defence of tourism, Azuma describes how tourism was, in the latter half of the 20th century and especially in the 1980s, often used to describe working-class people who could suddenly afford to travel. And while a working-class family might, say, go to Paris and only put the clichéd version of the city on the iritinerary (the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre) this leaves space for chance encounters or ‘misdeliveries’; firstly, a working class family going to see the Mona Lisa is more radical than it seems if the family don’t generally go to see art when they’re at home; but, secondly,there may be other unintended consequences: they might take a wrong turn on the way and end up seeing something that will change their perception of Paris, or see another, lesser-known artwork that might inspire their own creativity. Such points of contact offer the chance for the expansion of one’s cultural landscape.

In the late 1980s, when some of my earliest memories were formed, I remember how the often politically charged vinyl records my Dad had collected (Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Bob Marley, The Manhattans) struck me as curios when I’d catch a glimpse of them pushed away into a storage cupboard to make way for new CDs that seemed to signpost a different era; the dashiki shirts were gone, replaced by the suits and preppy sports-casual looks of Earl Klugh, George Benson, Luther Vandross, Peabo Bryson, Whitney Houston, and BeBe and CeCe Winans. Even here, though, was a visual world of Blackness that is worth taking seriously, because behind the record label’s conjuring trick of making Blackness more palatable to the mainstream was a sense of social mobility for the Black community, suggesting an elegant 1980s middle-class Black identity that I found deeply comforting as a child.

Paul Graham

Union Jack Flag in Tree, County Tyrone (1985, printed 1993–4)

Tate

© Paul Graham; courtesy Pace and Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

Then there was the postmodern avant-garde of Grace Jones, which, in collaboration with her then husband, the photographerJean-Paul Goude, offered a futuristic take on the way Josephine Baker played with and mocked notions of Black savagery in 1920s Paris. (More work should be done on the legacy of 1980s French photobook publisher, Love Me Tender: it was responsible not only for Goude’s Jungle Fever but also Cheyco Leidmann’s books Foxy Lady and Banana Split, which inspired a raft of 1980s album covers and music videos, including Duran Duran’s Rio). These aesthetics brought life, colour and optimism into our Sheffield terraced house, turning our front room into a vessel that looked out at the world.

In his essay ‘Ghosts of My Life: Goldie, Japan, Tricky’, Mark Fisher speaks of the type of suburban hinterlands that many of the new romantic singers came from, in this case the band Japan emerging out of ‘Beckenham, Catford, Lewisham, and the unglamorous conurbation where Kent joins South London’. Fisher writes of how, like many of the era’s singers, Japan frontman David Sylvian had created a voice and look that attempted to escape the drab reality of his hometown; ‘it couldn’t contrast more with Sylvian’s speaking voice at the time – awkward, tentative, strongly bearing all the traces of class and South London which his singing voice had sought to remove’.

This mimics many other famous bands from nowheresville in Britain at the time. Sade Adu, for instance, grew up in Essex, with the rest of her band’s members from Hull, yet they look and sound like a Cuban–American jazz band from New York City, and their CD slipcases were portals to that dreamscape. These album covers may not be encoded with the revolutionary politics of the 1960s but were quietly revolutionary in their own way.

Fisher is best known for his critique of a capitalist realism that thrives by swallowing up and commodifying any counter-narratives or alternative visions, using things such as the civil rights movement in advertising, for example, to empower mostly rich, white executives. However, he later wrote a compelling line in a review of the Otolith Group’s art work Anathema 2012, which suggests that while there may not be a way around such capitalist sorcery, we might chart a way out by going through it.

Perhaps having to think in such a way is a sign of the desperation my generation faced in the wake of the 1980s and the collapse of the Soviet Union – and with it any alternative vision; Ten.8 magazine went under in 1992, along with other Black British institutions such as the Keskidee Centre (Britain’s first arts centre for the Black community) in 1991, and magazine Race Today in 1988. I remember coming of age in the 1990s and 2000s, looking around and wondering what had happened, where everyone had gone. Later I learned that they had disappeared from a more central position in popular culture to enter elitist art and academic institutions that locked out working-class kids who worked in Debenhams – a move that the left still hasn’t recovered from. Speaking in her book Savage Messiah about more traditionally white working-class countercultures, such as punk,the squatting scene and rave culture, artist and author Laura Oldfield Ford eloquently describes how it felt to reach adulthood in the 2000s, haunted by the 1970s and 1980s: ‘always yearning for the time that just eluded us’.

Covers: Retracing Reggae Record Sleeves in London (2018): Aisha, High Priestess (1987)

Photo © Alex Bartsch. Cover: Retracing Reggae Record Sleeves in London published by One Love Books, 2018

It is another work, however, that offers the most eloquent response to our cultural malaise. In Covers: Retracing Reggae Record Sleeves in London, one of the most haunting and extraordinary photobooks of the 2010s, the photographer Alex Bartsch used reggae record sleeves from the 1970s and 1980s to superimpose ‘the time that eluded us’ into the present, collapsing eras and resurrecting geographies and visions of Black life that illustrate well Paul Gilroy’s point about their significance as cultural artefacts. Bartsch photographs various record covers, holding them before the exact location in London in which the original cover photos were taken, the images seamlessly blend into the surroundings decades later – and it appears as though a ghost and the forgotten history it carries has been captured within the frame. Perhaps it is the alternative, counter-hegemonic histories contained in such subaltern artefacts as album sleeves and magazines, and the work of those photographers they opened a space for, that will in the end suggest alternative futures.

Tate Britain

The 80s: Photographing Britain, until 5 May 2025.

Johny Pitts is a writer, photographer and broadcaster. Supported by Tate International Council and Tate Patrons. Curated by Yasufumi Nakamori, former Senior Curator of International Art (Photography) Tate Modern, Helen Little, Curator, British Art, Tate Britain and Jasmine Chohan, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain with additional curatorial support from Bilal Akkouche, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, Sade Sarumi, Curatorial Assistant, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain and Bethany Husband, Exhibitions Assistant, Tate Britain