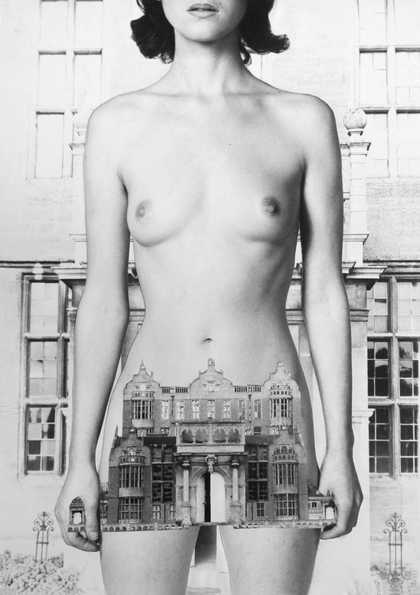

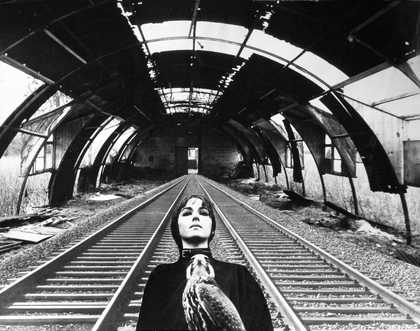

Penny Slinger

End of the Line 2 (1977)

Tate

When I was four and a half years old, I made my first accomplished drawing. It was of my parents, who were proud, because it was very good. However, I had drawn them both naked and fully sexually endowed, so they had the mixed emotions of feeling pleased but a little bit embarrassed to share it – a problem that I think pursued them throughout my career.

Being able to make marks was a great solace to me as a child. I tended to be something of a loner and I had a low boredom threshold. But I found that if I could make art, I was both never alone and never bored. So, very soon, art became my friend, and my life. If I was sick in bed, I would cut up magazines and make things. The joy of being able to create something from nothing had its charm right from that early time.

I worked very hard at school, because I was longing to get to art school. I took a two-year foundation course at Farnham School of Art, where I learnt bookbinding, pottery and weaving – all things that I would incorporate into my art. Afterwards, at Chelsea School of Art, I was a bit of a problem student in that you were supposed to be either in the painting, sculpture or printmaking department. I wanted to merge all these mediums, so they put me in a separate studio under the stairs. I also looked around me and thought: a lot of the girls here are more talented than the boys, so why is it that they are becoming artists and the girls aren’t? I wanted to change that.

The films I saw at the National Film Theatre were a great influence on me then – Jean Cocteau, or Luis Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou (1929), for example – and I loved the photography of Bill Brandt and Lucien Clergue, whose book Née de la Vague (1968) brought women’s bodies, the elements and landscape together, and resonated with my desire to describe and portray women in a much more liberated way. The psychological, the alchemical and the mythic were all woven into my appreciation and creation of art right from the start.

While doing my thesis on Max Ernst in 1969, I made my first book, 50% the Visible Woman, which I bound in snakeskin. I decided I wanted to use the tools of surrealism to plumb the feminine psyche, because I felt it was pretty virgin territory. I used photographic collage instead of the old engravings that Ernst had worked with, and I chose to use myself as my own muse. I wanted to look at and describe myself – I felt I could do a better job than someone else looking at me. I have pursued my interest in this way of looking at women, as subjects rather than objects, all through my life.

My degree show at Chelsea would combine sculpture, painting, film, collage and photography: casts of my head that showed the mutability of the self, a bride in the bath, a mummy case with bits of bodies inside, a suit of armour, and a big caryatid. Although my work has taken different persuasions, colours and shapes according to the situations I’ve experienced, all my ways of communicating with, and through, art are still very much embedded in those formative years.

Five photo-collages from Penny Slinger’s An Exorcism series were purchased with funds provided by the Photography Acquisitions Committee in 2018; three are currently on display at Tate Britain.

Penny Slinger is a London-born artist who lives and works in Los Angeles.