Heinz Mack

The Saffron Mirror Plantation, Tunisia, 1967

Archive Heinz Mack / DACS 2024

Eduardo Kac

‘We wanted to develop a vocabulary of the revolutionary power of happiness’

FIGGY GUYVER Your work has always involved cutting-edge technology, from artworks made using Minitel terminals to developing new forms of bio art. You’re also about to become the first artist to have an artwork installed on the Moon. How did you first encounter these new technologies?

EDUARDO KAC I’ve been an avid reader from a young age and, as a boy growing up in Brazil, I read encyclopaedias and dictionaries. When I was ten, I read one called, Conoscere il Nostro Tempo or ‘Knowing Our Time’, in which current things including cybernetics, computer art, and holography were discussed. I became fascinated by this other world opening up before my eyes.

FG That would have been during the late 1960s, early 1970s, right? I think of that as a time saturated with ideas of the future.

EK It’s interesting... I remember clearly the Moon landing. All the adults were very excited about it, but I wasn’t. I’d been reading in comics about people already living in outer space and moving between planets, so landing on the Moon seemed kind of late. And it paled in comparison.

FG It seems you’ve always been ahead of the times, or anticipatory. The porn art movement you were involved with in the early 1980s was very avant-garde. Could you describe the art you were making then?

EK There’s a photograph of me in a pink miniskirt, performing on Ipanema Beach, which alone tells you what was going on there. We were retaking the public space of the beach, where freedom of expression had been suppressed by the military under the dictatorship. It was an opening of possibilities, and it anticipated the gender-based work that is being done today.

Every avant-garde movement is a symptom of what’s missing from society. When you think of futurism and its embrace of technology, it wasn’t a reflection of the social reality of Italy – at that time, Italy was powered by horses! An avant-garde movement reaches for what isn’t there, and the porn art movement did just that.

The vocabulary of the 1970s, not just in Brazil, was a vocabulary of violence. We didn’t want that. We wanted to transform desire, to develop a vocabulary of the revolutionary power of happiness. For instance, when people say ‘fuck you’, they mean something aggressive. But that’s a perversion. It takes something that is supposed to be enjoyable and weaponises it to offend somebody.

One of the techniques that we developed was to take an expression and build a poem around it, so that when you encountered it, its meaning would not be that of a conduit of violence, but the opposite. Part of the humour came from that cognitive dissonance of experiencing so-called ‘curse words’ in poetic contexts that subverted their meaning. Graffiti was one of the practices of the porn art movement, because it was another way of reclaiming public space.

FG You went on to make a series of works for Minitel terminals, which was a videotex service and a precursor to the internet. What was this system, and why did it appeal to you artistically?

EK Well, Minitel is the name the French gave to their implementation of this medium, and it referred to the terminal itself not the network it was connected to. The UK had its own version, and Japan and Canada had it too. In Brazil, they implemented Minitel as a public service, so you had terminals at malls, libraries, airports. You could use it to do things like buy train tickets.

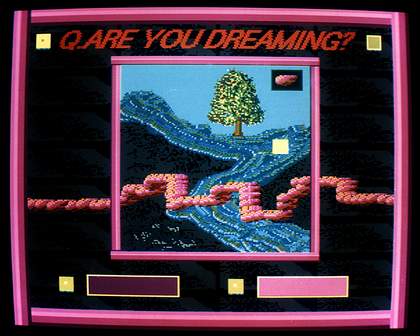

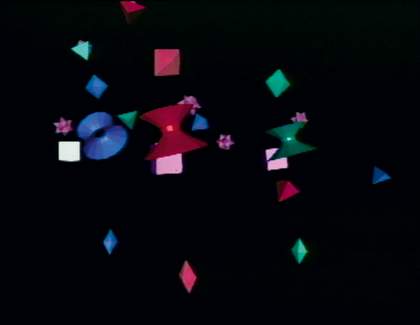

But I wasn’t interested in the way it was conceived. I wanted to develop my own form. The first work Reabracadabra, 1985, was my opening salvo, and it was a surprise in every way. The work begins with a green triangle, which loads fast, and is then quickly framed by a second, larger triangle. Lines are added to these shapes until you see a three-dimensional form appear, which is counter to what the Minitel is supposed to do.

Around the ‘A’ on the screen, dots that resemble stars begin to configure orbital positions. These stars then become consonants, and you realise that the vowel that structures the word ‘abracadabra’ is the nucleus. The consonants are now moons that orbit this nucleus. There is a relationship between the micro and the macro, the planetary scale and the microscopic.

One of the things that I have worked towards my entire career is undoing dichotomic systems, which serve power in specific ways. For instance, by articulating the difference between men and women, you’re able to oppress the other. By articulating the difference between X and Y, or human and non-human you’re able to create hierarchies. Once you remove those dichotomies, it becomes very difficult to use them as weapons of domination. This is also why I’m wearing my pink miniskirt on Ipanema Beach.

Eduardo Kac performing Interversão (Interversion) on Ipanema Beach, Rio de Janeiro, 1982

Photo: Belisario Franca

FG It’s interesting you connect this work back to the porn art movement. Tesão 1985–6, which is perhaps the most ambitious of the four Minitel works, seems more obviously related. The title translates as ‘horny’ and, over the course of three ‘movements’, that word is eventually spelled out.

EK ‘Horny’ is an approximation: there isn’t really an equivalent word in English. In Portuguese, it’s a word you can use to talk about yourself, what you feel, but it can also be an adjective that you apply to another person as an expression of desire. It’s not offensive – it’s an expression that indicates that you find that person attractive.

In the Tesão work you’re engaged with colour and movement, and not necessarily thinking in terms of language. It wouldn’t surprise me if even Lusophones [Portuguese-speakers] didn’t see language there. You’re mobilised by the action, by the form, the colour, the intensity, the sequence. But I’ve always been interested in how a person does that. Like with the graffiti work, how do you read it when you yourself are speeding by?

FG I read that Tesão was conceived for a particular person...

EK Yes. I was in a relationship that was, kind of, evolving. When the person in question came to the opening, I said, ‘I’ve got something for you. It’s online.’

FG What was their reaction?

EK It was an unusual thing for the time. But we’ve been together since then, so...

FG When you realised, in the early 2000s, that these works would cease to exist when the Minitel network was dismantled, how did you go about preserving them?

EK You never think that the things that form your surroundings will cease to exist entirely. But it’s a fact. Like the Minitel, there will be a moment of transition for the internet too.

When I realised that this change was taking place, I knew I would have to do something about it. Fortunately, years earlier, I had my friend take a professional photograph of every keyframe of every Minitel work which proved to be a useful reference. But these are not like traditional animation where you can interpolate between the keyframes. The transition from one frame to another is made by the system, not by you. So you have to create the liminal spaces.

Then there was the question of the technology. You see, the terminal didn’t do anything if it wasn’t on a network, and the network had ceased to exist. I finally managed to get access to... let’s call him an ‘artisanal engineer’ – somebody who was willing to reconstruct the pipeline.

In the end it took me 15 years to complete the process. But I’m not afraid of time – in fact, I think it’s fascinating.

FG This relates back to the idea of your work always being ahead of the point that people might be receptive to it. I wonder what you make of that?

EK Very often what I’m doing, what I’m interested in pursuing, is not yet part of the Zeitgeist or the common circulation of ideas, not yet close to the everyday experience of the audience. For that to happen, the passing of time is necessary. In the case of the Minitel, that was several decades, when even the phenomenon of the network itself no longer existed.

The kind of work that I do seems to have an embedded reception delay. The work Tate is showing is from 1985 to 1986. I was 23 then; I’m 62 now. The work I’m making now will probably find its audience in 30 years.

Eduardo Kac is an artist and poet. His latest work, Adsum, is scheduled to fly to the moon in 2025.

Eduardo Kac

Tesão (Horny), 1985–6

© Eduardo Kac

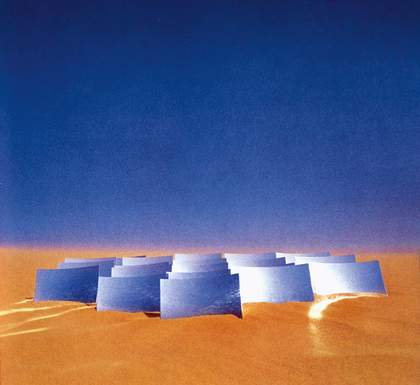

Heinz Mack

‘I was inspired by the idea of facing the horror vacui in the desert’

FIGGY GUYVER It’s been said that with your art, you wanted to ‘make the reflections of light manifest’. What led you to pursue light as the focus for your art?

HEINZ MACK I was born in 1931 in Germany, and growing up during the Nazi regime, it seemed to me that the whole world was dark. I remember vividly the air raids in my hometown: all windows were darkened, while the bombings looked like light apparitions in the sky. As a young boy, I was highly affected by this and I believe there is a deep psychological dimension to these early memories.

When I conceived the Sahara Project in 1959, I wanted art to find new freedom – away from the museums and institutions that, after the war, seemed like cultural cemeteries to me. The project was based on the idea that artistic works that capture, collect, and potentiate the light on their surface become vibrating ‘apparitions of light’ in an immense, light-flooded space such as the Sahara desert. As a young sculptor, I experienced the desert as a peaceful space that radiated calm. Here, I thought, my art could express the freedom to lead a positive life. In this sense, the Sahara Project can be understood as a counterpoint to the earlier darkness, a time when everyone was yearning for light.

FG Part of your 1968 film Tele-Mack, which will be screened in Electric Dreams, is filmed in the desert. What was it like to film there?

HM There had been no assignment to travel to the Sahara; the idea arose during filming. The director Hans Emmerling, the cinematographer Edwin Braun and their team had originally come to film in my studio in Mönchengladbach. When I told them about my ideas for the Sahara, they were immediately inspired and we spontaneously decided to film in Tunisia. With a truck full of material, the film crew and I set off to Marseille, where we took the ship to Tunis. When we arrived in the Grand Erg Oriental, a large field of sand dunes in the Sahara, it was new territory for the whole crew – only I had been there previously. Until noon it was freezing cold, then it got hot. The first days were dominated by uncertainty, but I was fortunate to be accompanied by cameramen whose empathy and sensitivity of vision made it possible to try many risky experiments. Everyone involved was inspired by the idea of capturing the various light phenomena on film in all their uniqueness and rich variation. The pace of work was hectic and yet I could have continued filming for weeks.

FG What was appealing about the setting of the Sahara?

HM The gravity of the desert, its absolute tranquillity, its endless dimensions – all this radiated mystery. In this landscape, infinitely vast and untouched, I now experimented with my comparatively small models and sculptures. This was inspired by the question of whether my art could stand up to this open landscape or would be lost in it.

I discovered that, despite the contradictory proportions, something could be created there that had a poetic radiance. In 1967, I travelled to Tunisia and installed my first bronze pillar in the desert. I noticed that the light of the sun immediately ‘took over’ the sculpture and increased its visibility. The pillar became an incarnation of light, the material of which was dematerialised, as it were. I could observe that the actual dimensions of the pillar seemed to change due to the vastness of the desert; the optical dimensions no longer corresponded to the physical dimensions. In the Sahara, the balance of real, virtual, and optical scales was negated.

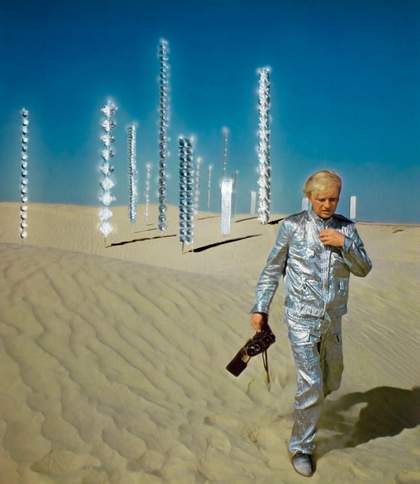

Heinz Mack during shooting for the film Tele-Mack in the Sahara desert, 1968

Archive Heinz Mack / DACS 2024. Photo: Edwin Braun

FG Tele-Mack is dated 1969, although work was begun on it the previous year. Seeing you dressed in a silver suit, and given the date, I can’t help but think of the Moon landings. Was that an influence?

HM Tele-Mack was filmed in the autumn of 1968 and aired on German television in May 1969. The Moon landing occurred in July 1969. It was an interesting parallel: just months before Neil Armstrong set foot on the Moon, I had walked in my silver suit through a deserted landscape much like the Moon’s surface.

Although the Sahara Project was conceived and realised during the Space Age, my silver suit was inspired by the fact that I had discovered the colour silver for my artworks. My Light Reliefs are made of aluminium or stainless steel, so that an immaterial relief of light can emerge on their surface, which manifests itself between the work and the spectator. I had worn the silver suit on other occasions, but in the Sahara it proved to be very helpful. Not only was I visible from afar – an object of light in the vastness of the desert – but the silver material also reflected the sunlight away from my body and thus had a cooling effect. During the filming of Tele-Mack, the film crew called me ‘Silver-Mack’!

FG Where did the name Tele-Mack come from?

HM I invented and suggested the title of the film myself. With Tele-Mack I wanted to express the fact that television has the same significance as art. I saw an opportunity to make television a partner of art. After all, it allows you to reach a large audience, including people who don’t normally find their way to a museum or gallery. In this sense, the film also has a social dimension. The only person who thought the same way was video artist Gerry Schum. I had conversations with him in which we asked ourselves: What function can television have for art? Schum then developed his fernsehgalerie (television gallery) and a collaboration was in the works when his life came to a sudden and tragic end.

FG Before you made Tele-Mack, you founded the ZERO group with Günther Uecker and Otto Piene (whose work is also included in Electric Dreams). The name seems to convey a sense, or maybe a desire, for erasure or for new beginnings. Is that true?

HM In the mid-1950s, discussions with fellow student Otto Piene led to the decision to publicly declare the ideas we shared artistically. This went hand-in-hand with the decision to abandon what we had already learnt, to forget as much as possible. Intuitively, I was inspired by the idea of leaving the cultural landscape and facing the horror vacui in the desert.

The ZERO group, founded by Otto Piene and me in 1957, was for Piene ‘an immeasurable zone in which an old state merges into an unknown new one’.

For me, it was the end of 500 years of art in which central perspective and composition had dominated. This new beginning dominated the atmosphere in our studios. Light became the material of design. I was inspired by the dream of dematerialising matter, and so I called my metal reliefs ‘light reliefs’. Uecker joined us in 1961, creating a vital team that was later referred to as the ‘triumvirate’.

FG Thinking back to the 1960s, what were your hopes, dreams and fears for new technologies at that time? And what are your dreams for the future now?

HM In the mid-1950s, when I was working with the ZERO group, we were fascinated by space travel. We were optimistic about life and expected a positive future. Through our experiments, we discovered that art, technology, nature and ultimately the cosmos were interrelated.

I am not afraid of technology, even today. The future will be determined by the new developments made by scientists, technicians and engineers. Of course, I hope that what is technically possible today – current phenomena such as artificial intelligence, but also older technology such as the atomic bomb – will not be misused.

Heinz Mack is a German sculptor and painter, best known for co-founding the Zero Group. His work explodes the interplay of light and materials, creating dynamic effects with reflective surfaces and kinetic sculptures.

Documentation of Heinz Mack’s Sahara Project, 1968

Archive Heinz Mack / DACS 2024. Photo: Edwin Braun

Rebecca Allen

‘I wanted to blow people’s minds and break the rules’

FIGGY GUYVER Where did your interest in making art using new technologies come from?

REBECCA ALLEN As a student, I was interested in art movements of the early machine age – the Bauhaus, constructivism, futurism – where artists were using new tools to create new forms of art and to think beyond realism. I thought that the computer age would be next, and that it would be important for artists to work with the computer at an early stage, to see if we could mould it to become an artistic tool.

I made my first digital artwork in 1974, a piece called Girl Lifts Skirt, while I was studying at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). Next door was Brown University, where they were doing early work in computer graphics and animation, so I talked my way in and created my first animated film of a female figure. I wanted to pursue something that you weren’t seeing much in computer science or even in art at the time: a woman working with a female figure, with female motion.

FG Why were you drawn to the idea of human movement?

RA I had been working with static forms of art, but wanted to move into time-based work, to think particularly about motion. My strongest interest was in studying human motion and nonverbal communication, how our slightest movements or gestures can affect our expression and convey so much.

When I started to work with a computer, there was an idea that it was only for numbers. It seemed to lack humanity. Working with the figure was my way of inserting the human into the computer. It was especially interesting to try to put femininity into it too. I could see, from the very beginning, that everything was being invented and defined by a narrow group of people – typically computer scientists, pretty much all male. I thought, this is too important to society and to the arts; it needs to have different perspectives.

FG You said in an interview that the traditional art world ‘couldn’t love anyone working with computers’. Why do you think the art world has been sceptical, or even suspicious, of art made using digital technologies? And does that suspicion still exist?

RA When I proposed an independent study in computer animation at Brown University, RISD said, no: it didn’t make sense, artists and computers. I didn’t agree but I don’t really blame the art world, because, from the beginning, computers were seen as some- thing frightening, something superhuman. There was a fear that they would replace us.

In a way, those fears are turning out to be true. It’s just that it took 50 more years for it to happen. Computers, robots, AI are replacing a lot of human endeavours. Since the beginning of my work with computers, though, I felt like art needed to respond to this, not run away from it.

FG By the early 1980s you had begun making music videos. How did that come about?

RA In 1981, MTV launched and I thought, wow, this is a way I can make experimental films with exposure to a large audience. I ended up making a video for Island Records for a song by Will Powers called Adventures in Success, which became extremely popular. Shortly after, I did another video for Will Powers called Smile, where I worked with a new form of movement – breakdancing – and created geometrical forms that performed breakdance movements with the live performers. That video was very popular too, especially in clubs.

Rebecca Allen embraces a Kraftwerk mannequin during the making of the music video for Musique Non Stop, 1984

Photo: Linda Law. Courtesy of Rebecca Allen

FG You made a few video works for clubs around that time, including Creation Myth 1985. What was the scene like, and can you describe the work you were making?

RA In 1985, I was commissioned by Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell (of Studio 54 fame) to create a video installation for their new large-scale New York nightclub, Palladium. The art scene in New York at that time was very popular, so Ian wanted this club to have an art theme. He commissioned a number of artists to design parts of the space, including Keith Haring, Francesco Clemente and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Creation Myth was about the birth of a new environment. There were some exciting software developments in my lab that could explore what today might be called generative art. I discovered how forms and movement from nature could be simulated using unique fractal and particle system software to create fire, water, atmosphere, plants and animals. In this work, the evolutionary process ends with a tree dancing in a disco.

FG You also made a video, Musique Non Stop, for the German group Kraftwerk. Why did you choose to make it look the way it does? Were you thinking about any references from art history when you made it?

RA My idea was to make digital models of their mannequin heads and bring them to life in the virtual world. After being recognised for my early work in 3D motion of the human body, I wanted to work on an equally hard and compelling problem, which was to animate a computer model of a face: for it to come alive with the ability to talk, look, express – and sing.

I also wanted to define a uniquely digital aesthetic. The faces aren’t smoothly shaded, the way a photograph of a face would be. Technically, they are faceted, but I called it ‘cubistic’. I was also inspired by Tamara de Lempicka’s paintings, which is where the bright lips and blue faces come from. The only realism I included was in the eyes, which were photographic. Kraftwerk’s music has a tight digital feel to it, so I wanted the video to reflect those robotic movements too.

I also just wanted to blow people’s minds and break the rules. The heads looked solid, but using digital technology, one head could go through another. I could zoom in and you would see pixels.

FG It’s almost like showing some of this inner working is to make people aware of the technology used to make it?

RA When you work in a virtual, three-dimensional world, you follow processes that I found fascinating, and I wanted to explain them. For the Electric Café album cover, for instance, I created a portrait of Kraftwerk, using the four heads. The back cover showed the back of their heads – I was trying to show that they are three-dimensional forms. Inside the album cover are images of the process of making the artwork, and on the record sleeve is the wire frame. The idea is that you are going inside, seeing the skeleton. I loved revealing the process, because it was all so new.

FG It’s an interesting thing about computer art from this time – it was so specialist that so few people, especially in the traditional art world, had any technical knowledge. What was the reaction to your work?

RA In those days, when I would talk to people in the art world, they would say things like, ‘I don’t know anything about computers’, and I would think, you don’t know how to sculpt, but you can look at the form, the colour, the shape, the movement. You can judge this work in similar ways to other types of art.

Rebecca Allen

Steps 1982

© Rebecca Allen

FG What do you make of the recent, rapid advancements in technology? I’m thinking of AI, as well as virtual reality, which you’ve explored in more recent work.

RA During the first few decades of working with emerging technology, I would always say that the ideas were ahead of technology. Now, I feel technology is racing ahead of the ideas at a non-human pace. There isn’t enough time to reflect on what we’re creating. The technologies that we’re inventing are having a profound effect on what it means to be human. It’s redefining our sense of reality and identity, and our relationship to nature and the physical world. We can’t digest or even anticipate these developments and their effects before the next advancement comes along.

AI is the latest powerful technological advancement that will prove to be very good and very bad. Or take virtual reality: does anyone really want to live there, and if so, where do our bodies go? I’m interested in thinking about the way technology is changing our bodies. I feel as if humans, for some reason, are trying to leave the physical world and I explore this in some of my work.

With my work now, I don’t want to be 20 years ahead anymore. There is so much out there already that hasn’t yet been explored. I’ve always thought that it was the role of artists to think more deeply about the state of the world and present their ideas in a way that resonates with their audience. It seems old-fashioned now, very modernist thinking maybe, to use art to interrogate society and where it’s going. But that’s my interest in the arts, and I still believe in it.

Rebecca Allen is an American artist inspired by the aesthetics of motion, the study of perception and the behaviours and the potential of advanced technology.

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern, until 1 June 2025.

Presented in the Eyal Ofer Galleries. In Partnership with Gucci. Supported by Anthropic. With additional support from The Electric Dreams Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons. Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor. The media partner is The Times and The Sunday Times. Curated by Val Ravaglia, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, and Odessa Warren, Assistant Curator, International Art (Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational), Tate Modern.