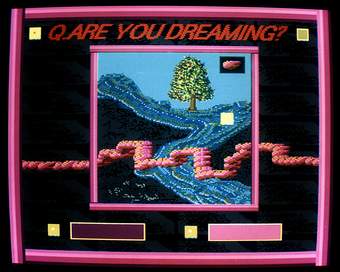

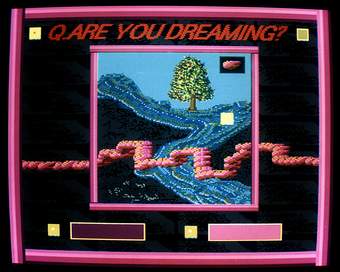

Suzanne Treister Fictional Videogame Stills/Are You Dreaming? 1991-2 © Suzanne Treister

Find out more about our exhibition at Tate Modern

Suzanne Treister Fictional Videogame Stills/Are You Dreaming? 1991-2 © Suzanne Treister

Eduardo Kac Horny 1985 Lent by the Tate Americas Foundation © Eduardo Kac

This exhibition brings together a network of artists inspired by scientific ideas and technologies. It tells a series of loosely connected stories about the early innovators of electronic art, from the 1950s to the widespread adoption of the internet in the early 1990s. Collaborating internationally, they experimented with cutting-edge media and hybrid methods to expand their collective creative horizons. Many believed technology should be a communal resource, working together to steer its development towards creative and social uses.

Some artists in the exhibition used electronics to shape light and sound. Others introduced mathematical principles and algorithms as creative partners. New fields of study, such as cybernetics, encouraged artists to think about the relationship between artworks and their audience as a ‘communication system’. Viewers became active participants. Applying emerging technologies and scientific principles to art made it possible to interact with it in new ways.

Breakthroughs in telecommunications allowed artists to collaborate across international boundaries, forming networks and communities. Computers went from the size of a room to discreet boxes sitting on a desk, transforming how people could work. For some, engaging with technology was a way of reclaiming it from the military and corporate interests that had driven its development. Many artists tinkered in high-tech research labs or with consumer electronics, often sharing access to expensive equipment with each other and their communities.

Electric Dreams is roughly chronological. Immersive installations of large-scale works combine with rooms exploring artists’ shared interests and collaborations. It contains a wide range of ideas and technologies, from paintings inspired by mathematics and the science of perception to the earliest experiments with virtual reality. As technology continues to shape the world in ways we can’t yet imagine, this exhibition presents how earlier artists coupled scientific thinking with human creativity.

What interests me most during the creative process is the switching on and off of the electric light bulbs. When I turn on the switch and the motor starts, the electric bulbs that I have installed take on an unreal beauty as if they were not made by human hands.

Atsuko Tanaka

Atsuko Tanaka’s Electric Dress is a sculpture, painting, installation and costume all at once. Created for a performance in 1956, Tanaka made the wearable artwork from hand-painted industrial bulbs and incandescent tubes. It was uncomfortably hot, heavy, and in the event of a short circuit, potentially deadly.

The idea for the dress came as the young artist waited for a train at Osaka Station, surrounded by neon advertising signs. Barely ten years after the end of the Second World War, the novelty of the electrified cityscape expressed the complexity of a new, developing Japan. Through Electric Dress, Tanaka could explore her intimate relationship to these emerging, everyday technologies.

Tanaka created Electric Dress while working with the Gutai Bijutsu Kyokai (Gutai Art Association), active in Japan between 1954 and 1972. Its founder, artist Jirō Yoshihara, called for the group to ‘do what no one has done before!’. Tanaka’s engagement with the visual language of technology and her presentation of electricity as an extension of the human body was highly unique at that time. Her favourite part of the Electric Dress performances was when she turned on the in-built motor, causing the lights to ‘blink like fireworks’.

Cybernetics is the science of systems. It studies how systems behave and interact in machines, living beings and the wider world. The field was first developed during the Second World War by the US mathematician Norbert Weiner while working on a ‘predictor device’ that could increase the aiming accuracy of anti-aircraft guns. Early cyberneticists focused on principles of ‘control’ and ‘communication’. They produced systems that could ‘self-regulate’, adapting themselves in response to their external environments.

As the field gained international popularity in the 1960s, second-generation cyberneticists introduced principles of ‘observation’ and ‘influence’. This allowed them to link systems together into complex ecologies. Cybernetics became applied more widely to various social, environmental and philosophical contexts. It developed a cultural dimension among the 1960s hippie counterculture. They experimented with new technologies alongside their interest in alternative lifestyles and mind-altering experiences.

Many artists and thinkers turned to cybernetics to make sense of a newly interconnected world, increasingly driven by technological development and interactions with machines. As a field concerned with constructing systems, cybernetics also holds the potential to dismantle existing structures and rebuild them anew. Artists responded to these ideas by creating systems-based works that performed creative acts with minimal human intervention, or which responded in real-time to the interactions of their viewers

The 1950s saw rapid developments in science and technology. Recent discoveries such as quantum fields, DNA and microcircuitry presented new questions about the nature of reality. Transistor radios and other communications media were developed, making it possible to interact in unusual and exciting ways. By the end of the decade, many homes in affluent parts of the world had telephones and televisions for the first time. Probes were launched into space by the United States and the Soviet Union, and the increasing possibility of human space travel fired imaginations around the globe.

Artists saw the newly visible expanses of science and space described by physicists as a challenge to visualise what was barely thinkable. Electricity and simple, analogue ‘programs’ often played a crucial role in their work, alongside cosmic landscapes, optical experimentation and mathematical principles of growth and change. Many of the works in this room are ‘kinetic’, a term used for artworks in which movement is an essential component.

This section of the room presents a selection of artists working with technology and mathematics in London during the 1950s and 1960s. With the art gallery Signals London as their creative hub, they brought a vibrant, diverse and adventurous artistic scene to the city. The artworks on display here demonstrate early approaches of thinking through ‘systems’, and other cybernetic principles.

In early 1964, artists David Medalla, Gustav Metzger and Marcello Salvadori, along with art critic Guy Brett and curator Paul Keeler, set up the Centre for Advanced Creative Study. The gallery was soon renamed Signals, after a series of sculptures by the kinetic artist Takis. Their exhibitions featured cutting-edge works by artists from Latin America, Europe and Asia. They shared an interest in creating interactive, generative and participatory works using light, air, gravity, motion and energy.

Signals developed an ambitious and influential artistic programme over the following three years. International artists such as Takis, Liliane Lijn and Jesús Rafael Soto were invited to exhibit in London, often for the first time. The organisers also published Signals Newsbulletin, a publication discussing the intersections between visual arts, poetry, science and technology.

Heinz Mack during the shoot of the film 'TELE-MACK' in the Sahara desert, east of Oasis Kebili, Tunisia, 1968. Photo: Edwin Braun/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2024, DACS, London, 2024

Zero is silence. Zero is the beginning. Zero is round. Zero spins. Zero is the moon. The sun is Zero. Zero is white. The desert Zero. The sky above Zero. The night.

from a poem by Heinz Mack, Otto Piene and Günther Uecker, 1963

The Zero group was founded by artists Heinz Mack and Otto Piene in Düsseldorf, Germany in 1957, joined by Günther Uecker in 1960. As collaborators, they shared a utopian view of the future and how art could transform society. Taking their name from the countdown for a rocket launch, Zero aimed to create ‘a zone of silence and of pure possibilities for a new beginning’.

The group reacted against traditional approaches to painting, which emphasised the role of the individual artist and their subjective feelings. Instead, Zero artists often worked collaboratively. They used materials and techniques that incorporated light and motion, aiming to directly engage the full range of their viewers’ senses.

Mack, Piene and Uecker organised lively and immersive one-night exhibitions (Abendausstellungen). These began in their shared studio and gradually evolved into outdoor events and large-scale projects. The exhibitions featured a growing roster of friends and collaborators from Europe, Japan, North and South America, some of whom are on display in this room. They began referring to this wider, loosely-knit international network as ZERO (in capital letters).

I go to darkness itself, I pierce it with light, I make it transparent, I take its terror from it, I turn it into a volume of power with the breath of life like my own body.

Otto Piene, 1973

Zero founder Otto Piene’s Light Room (Jena) is installed in the following room. Five light-emitting sculptures with motors are synchronised to create a theatrical light play or ‘ballet’. The work demonstrates Piene’s life-long interest in using light as a material to stage immersive visual experiences.

Piene experimented with stencils during Zero’s single-night exhibitions, organised by Piene and Heinz Mack in their Düsseldorf studio. He found that he could create dramatic moving projections by shining light through perforated holes with a candle. Piene exhibited his first arrangements of light machines, Light Ballet in 1959. The machines shown here mostly date from the 1960s, when his kinetic installations became increasingly performative. Evolving into mechanised environments, they feature metal screens, discs, motors, timers, and rotating electric lights. Piene brought these sculptures together as one installation in 2007.

In 1968, Piene became the first international fellow of the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). CAVS had been founded by artist György Kepes the previous year. Piene was instrumental in bringing other artists to MIT, making CAVS an innovative and influential platform for experiments bringing together art and technology.

The Dream Machine may bring about a change of consciousness inasmuch as it throws back the limits of the visible world and may, indeed, prove there are no limits.

Brion Gysin, 1962

Brion Gysin was a painter, poet, performance artist and inventor of experimental devices. In 1959 he created the Dreamachine, a meditative rotating light sculpture and ‘the first art object to be seen with the eyes closed’. He refined the design with the creative technologist Ian Sommerville, in conversation with the novelist William S. Burroughs. Gysin and Burroughs were key figures in the Beat literary and countercultural movement, a group of underground writers and thinkers who critiqued society and experimented with psychedelic drugs.

Gysin was inspired by an experience he had on a Marseille bus in 1958. He saw bright patterns behind his closed eyelids, caused by sunlight passing through trees. He recalled, ‘An overwhelming flood of intensely bright patterns in supernatural colours exploded behind my eyelids: a multidimensional kaleidoscope whirling out through space.’ The Dreamachine is intended to be experienced with both closed and open eyes. Gysin hoped to produce a flicker effect, triggering alpha waves and generating coloured images in the viewer’s brain.

This room also contains literary collaborations between Gysin and Burroughs. Gysin popularised a writing method he called the ‘cut-up’, featuring fragments of texts snipped out of magazines and randomly reordered. Burroughs adopted the practice, collaborating with Gysin on several ‘cut-up’ books. Gysin also produced ‘permutated’ poems, which could be arranged in various ways to produce multiple meanings. With Sommerville, he generated some of these poems using a computer. Together, these approaches sought to engage with language itself as a technological system, influenced by chance and magical thinking.

This room presents a selection of Katsuhiro Yamaguchi’s explorations in new technologies. Working and teaching across a range of experimental artistic disciplines from the 1950s onwards, Yamaguchi’s work helped to popularise art using emerging media in Japan. He was creatively prolific, collaborating with architects, designers, filmmakers and musicians.

Yamaguchi co-founded the artist collective Jikken Kōbō (Experimental Workshop) in 1951. The group’s uniting principles were to embrace artistic experimentation and creative collaboration. Artists worked alongside engineers, composers and creatives, blurring the boundaries of traditionally defined artistic disciplines. They staged public exhibitions and performances in unusual places, conjuring aesthetic experiences through new technologies of sound and optics.

In the 1960s, Yamaguchi continued his experiments with new media by making sculptural light forms from acrylic and glass. He also produced some of the earliest video works shown in Japan. Throughout his life, Yamaguchi remained deeply concerned with the pervasive presence of consumer advertising, the accelerated pace of technological advancement, and the resulting transformation of our lived environments.

Many of the artists in this room belonged to the Italian Arte Programmata (Programmed Art) movement of the 1960s. Artists interested in kinetics, mathematical rules and modular design formed distributed groups in Milan, Padua and other locations. The writer and theorist Umberto Eco promoted the movement, and his book The Open Work 1962 was fundamental for many kinetic artists. It places emphasis on ‘openness’, leaving space for change, chance and interaction.

The work of Arte Programmata artists was influential for the early phase of Nove Tendencije (New Tendencies), an international movement of artists inspired by scientific research and the nature of vision. New Tendencies developed out of an exhibition of the same name organised in Croatia in 1961 by the artist Almir Mavignier and art critic Matko Meštrovic. Hosted by Zagreb’s Gallery of Contemporary Art, this was the first of five Tendencies exhibitions. It featured optical effects, colour fields, geometry and kinetics, including many works by artists from the Zero circle. Several artists in this room showed work in Tendencies exhibitions throughout the 1960s, turning Zagreb into an international hub of the evolving movement.

Most New Tendencies and Arte Programmata artists considered their work as a form of ‘visual research’. They used scientific and mathematical principles as ‘programmes’ to generate artworks. Experimenting with fundamental sciences allowed artists to cut across cultural backgrounds and connect with international audiences in new ways. They believed that this kind of art could be more democratic, relevant to everyday life and thus socially beneficial.

We want to make audiences show an interest, shed their inhibitions, and relax.

We want them to take part.

We want to place them in situations they can trigger and transform.

We want them to be aware of their participation.

We want them to tend towards interaction with other audience members.

We want to help audiences develop their ability to perceive and act.GRAV ‘Enough with the Mystifications!’, 1963

This is an extract from the manifesto that Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV) wrote for the 1963 Paris Biennale. It was a declaration of intent: GRAV artists wanted to make art that engaged directly with the public, fundamentally rethinking the artist’s role in society. They favoured collective activity and worked against notions of the artist as an individual genius.

GRAV was founded in 1960 by a group of young international artists who converged in Paris. Among those at the forefront of the group were the French artists Jean-Pierre Yvaral and François Morellet, the Spanish artist Francisco Sobrino, and the Argentinian Julio Le Parc. Like other artists linked to the New Tendencies movement, GRAV were inspired by mathematical principles and pre-determined systems. Their works included paintings and constructions that played with sensorial perception by using striking optical effects and contrasting colours.

From 1960 to 1968, GRAV organised a series of interactive events called Labyrinths. These group exhibitions consisted of immersive environments with mounted reliefs, light installations and kinetic components. They were laid out in a sequence of narrow passages that visitors were invited to explore. The various mechanisms and components had to be ‘activated’ by the public, resulting in a collective experiment that changed every time. Works by Le Parc and Morellet, including the wallpaper in this room, are on display here.

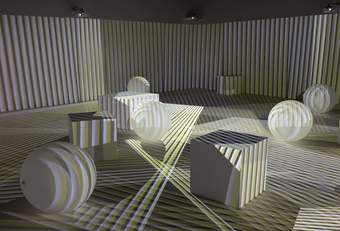

Carlos Cruz-Diez Environnement Chromointerférent, Paris 1974/2018 © Carlos Cruz-Diez / Bridgeman Images, Paris 2024

When light comes into contact with an artwork, it changes it completely. My challenge is to reveal to the viewer a reality without a past or a future: my works exist in a perpetual present.

Carlos Cruz-Diez, 2019

Carlos Cruz-Diez’s immersive installation Chromointerferent Environment fills the following room. A sequence of moving parallel lines colour the gallery floor and ceiling. The projection is constantly in motion, changing the appearance of the objects and people in the room. This creates a disorientating effect. Visitors are invited to interact with the cubes and balloons positioned around the room, engaging directly with the dizzying optical patterns.

Cruz-Diez experimented with different properties of colour and light to generate visual illusions. This work is based on the effect generated by the movement of overlapping patterns. As a result, the human eye sees colours that are not in the source materials. Chromointerferent Environment was originally installed in 1974 using slide projectors with a 35mm frameless roll. A moving pattern of black lines was projected onto white panels painted with red, blue, and green lines. This chromatic interference was transferred onto the objects and people in the space.

The installation seen here is a digital realisation of the original work. This version uses high-definition video projection created with a computer graphics program developed by the artist with his son, Carlos Cruz Delgado. The lines and speed are more varied, which means the colour combinations increase, and there are infinite possibilities for visual interference. Like GRAV’s Labyrinths, Chromointerferent Environment turns viewers into active participants, interrogating the relationship between artwork and audience through visual effects. Cruz-Diez

Harold Cohen AARON #1 Drawing 1979 Tate Purchased 2015 © Harold Cohen

This room focuses on the rise of computers and electronics as tools for making art from the 1960s onwards. The Second World War significantly sped up the development of computer-based technology. Innovations such as display screens meant data could be visualised and manipulated in increasingly sophisticated ways. However, access to these machines was extremely limited. Many of the early computer artworks were created by mathematicians and engineers working in research laboratories equipped with room-sized computers like the IBM 7094, a machine also used by NASA in the Apollo space programme.

Programming languages like FORTRAN, originally designed for scientific computing, enabled artists to use mechanical tools in innovative ways. Some artists learnt how to use code so they could communicate with scientific devices, instructing them to draw lines and shapes using screens and plotter printers. At the same time, advancements in electronic components made new kinds of interactive artworks possible. Electronic sensors could detect sound and movement, allowing artists to create new ways for artworks and audiences to interact.

The 1960s saw the first wave of group shows displaying computer art. The first in the UK was Cybernetic Serendipity, which opened at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London in 1968. It explored the creative potential of technology beyond the visual arts, including electronic music, dance and poetry. In 1969, the international touring exhibition Arte y Cibernética (Art and Cybernetics), organised by the experimental workshop Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAYC), opened at Galería Bonino in Buenos Aires. The New Tendencies gatherings in Zagreb also embraced the move towards computers and visual research. The exhibitions Tendencies 4 in 1968–9 and Tendencies 5 in 1973 brought together early digital artworks from four continents.

Cybernetic sculpture … expresses a firm belief that scientific innovations when properly oriented to serve humanity … can be an effective means of delivering us from our present environmental chaos into a world of dynamic ecological equilibrium.

Making use of his background in engineering, Tsai merged mechanics, electronics and optics to create kinetic works that respond to their environments. In the mid 1960s, Tsai began creating Cybernetic Sculptures, works that reference ‘the poetic unfathomable wonder of the universe’.

Square Tops and Umbrella, the two cybernetic sculptures on display in this room, are made of vibrating metal rods lit by strobe lights. Although the rods vibrate at a constant rapid rate, the stroboscopic effect of the flashing lights creates the illusion of a slow, undulating movement. Viewers can interact with the works via an audio feedback control system: singing, stomping or clapping increases the frequency of the strobe flashes. This action creates an optical effect, making the rods’ movement appear to change in a varied manner. When visitors leave, and the room falls silent, the system returns to its original homeostatic state.

Tsai’s cybernetic works were first exhibited in 1968 at a solo show at New York’s Howard Wise Gallery, a venue closely associated with kinetic and electronic art forms. His work was also featured in the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition at ICA, London. While Tsai continued to develop his cybernetic sculptures throughout his career, he also experimented with different media and technologies. In the late 1970s, he began creating works with light, colour and water elements controlled by computers.

Visitors are welcome to clap, sing or play music out loud in the room (for example from your phone) to interact with the work.

For many years, the only way creative practitioners could work with expensive hi-tech tools was to collaborate with the institutions and corporations that owned them. However, by the end of the 1960s, electronic consumer products became more widely available to the general public. This room focuses on artists experimenting with the new tools at their disposal, often repurposing them and inventing new ones, bringing a ‘Do It Yourself’ attitude to the introduction of emerging media in art.

In the 1950s and 1960s, tech companies like Bell Laboratories and IBM offered several ‘artist-in-residence’ programmes. Artists often developed innovative applications for new technology, leading to significant breakthroughs. Rebecca Allen invented new motion capture and 3D modelling, bringing her artistic practice into software engineering, and Nam June Paik was the creative force behind one of the first video synthesisers. In the 1980s, personal computers and graphics editing software became commercially available. Artists seized the opportunity to experiment with electronics on their own terms.

Venues like London’s New Arts Laboratory and Centro de Arte y Comunicación in Buenos Aires were founded to foster international collaboration, hosting early experiments with video and ‘intermedia’ work. The 1972 exhibition Video Communication: D.I.Y. Kit in Tokyo, Japan led to the establishment of Video Hiroba, an experimental collective that saw video technology as a community resource and alternative to mainstream media. Countercultural movements opposing mass consumerism and corporations’ control of telecommunication and technological resources began to emerge. Many publications, such as the Whole Earth Catalog and Radical Software, encouraged people to develop their technical skills to reclaim technology for creative and social uses.

The whole is a study of models of the world, of outer space, of time and of human society.

Tatsuo Miyajima, 1993

This room presents two of Tatsuo Miyajima’s works from the 1990s. Lattice B and Opposite Circle are both made from two-digit LED number counting units arranged in geometric formations. The 40 intricately connected LED units of Lattice B are presented on a wall. In Opposite Circle, the LED displays form a three-metre ring that appears to hover a few centimetres above the floor. The counters are programmed to move upwards from one to 99 in a unique rhythm before resetting. The overall effect is a flickering and ever-changing display of numbers progressing at different speeds. The works are part of Miyajima’s series 133651, the title of which refers to the 133,651 potential combinations of the two works.

Miyajima’s practice is inspired by three guiding principles: ‘keep changing’, ‘connect with everything’ and ‘continue forever’. These ideas are inspired by Buddhism. The artist explains, ‘In Eastern and Buddhist philosophy, change is natural and consistently happening’. Technology allows Miyajima to articulate philosophical ideas about life cycles and repetition using light, time and movement. Modern technology is not ‘an end in itself’ for the artist, but a means of visually representing his ideas and visions. He says, ‘It is not about creating a beautiful image or system, it is more about creating an inner spiritual quality in the world. My idea of the future is not a pictorial image but a spiritual concept.’

The purpose of Experiments in Art and Technology is to catalyse the inevitable active involvement of industry, technology and the arts.

E.A.T. News, Vol. 1, 1967

Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) was a creative group founded in the United States in 1967 by engineers Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer with artists Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman. Its goal was to promote collaboration between artists and engineers. E.A.T. organised technically daring projects and developed a programme of residencies with renowned artists, musicians, choreographers and composers. The works and archival material in this room focus on the years 1967 to 1972. They capture a snapshot of the international network of people and places connected to the group’s activities.

E.A.T. famously took part in Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan. The 1970 iteration of the World Exposition – the first to take place in Asia – featured pavilions commissioned by national governments and corporations, with a strong focus on new technologies. On the invitation of Pepsi Cola, E.A.T. designed the Pepsi Pavilion as a sequence of immersive environments. It contained laser and sound installations, as well as an enormous hemispherical mirror. A fog sculpture enveloped its exterior. The room also includes some contextual material on Expo ‘70 at large – and artists’ critiques of its use of art as promotional spectacle.

While developing the Pepsi Pavilion, E.A.T. connected with the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad, one of several experimental hubs emerging in India at that time. In 1971, NID collaborated on E.A.T.’s Utopia: Q&A 1981 project. This one-month event connected E.A.T. outposts in Stockholm, New York, Tokyo and Ahmedabad through telex machines in a participatory project that represented the culmination of E.A.T.’s international collaborations. It anticipated the spirit of chatrooms and message boards years before the invention of the internet.

My feelings about science – in particular the physics of light and matter – are that they are pure poetry.

Liliane Lijn, 2018

This room explores Liliane Lijn’s experiments with light and industrial materials. Since the 1960s, exploring new technological practices in the service of art has been at the forefront of Lijn’s practice. The works on display in this room, made in the 1980s, demonstrate her continued interest in electricity and other forms of energy.

Lines of Power is one of a series of rotating copper sculptures called Linear Light Columns. The work consists of tightly wound bands of copper wrapped around motorised and slowly revolving cylinders. A light beam falls onto the reflective copper surface, creating a hypnotic pattern. Copper is a material commonly used to conduct electricity. The light effects animating the work’s surface appear to travel endlessly down and around the cylinders, resembling a live current.

The dramatic figure of The Bride pulses with energy. It speaks to the artist’s interests in mythology and death, as well as in the sculptural properties of light. Lijn described the imposing enclosure as ‘offering protection to the fragility’ of the Bride figure behind it, rather than trapping her. Mica crystals, feathers and papier-mâché egg-like forms can be seen through the mesh. The work represents Lijn’s interest in spiritual, feminist approaches to the material world. She said, ‘I wanted to find a new way of looking at the feminine and to bring into that everything: plants, animals, humans and machines.’ By highlighting The Bride’s feminine qualities, Lijn opposes the common perception of mechanical materials and processes as inherently masculine.

Monika Fleischmann & Wolfgang Strauss Liquid Views - Narcissus Mirror 1992

The interactive stage manifests itself as a thinking space where art, science and technology are intertwined.

Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss, 2015

Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss were among the first artists to create immersive digital artworks featuring interactive technologies. Their work Home of the Brain 1989-91 was likely the first virtual reality artwork to make use of a head-mounted display and a dataglove. These devices, still in use today in videogames and virtual reality settings, allowed people to explore a simulated 3D space created by the two artists. In this cyberspace, viewers encountered the voices and ideas of philosophers commenting on the rise of digital media technologies.

Liquid Views – Narcissus’ Digital Reflections, on display here, features a touchscreen simulating a pool of water. The pool ‘reflects’ the viewer’s image, captured by a camera. The image distorts as the screen is pressed, generating rippling effects on this virtual liquid reflection. At the same time, the participant’s distorted image appears on a large screen allowing an audience to watch this interaction. The installation uses video texture mapping software, generating visual effects in real time.

When the work was made in 1992, interaction with one’s digitised image was still a completely new experience. According to the artists, ‘the encounter of the self with a shadowy virtual doppelganger [acts] as a metaphor for the internet and predicts the emergence of the Second Self as a selfie data body.’ Liquid Views echoes the ancient Greek myth of Narcissus, who fell in love with his own reflection in a pool. He then pined away, realising his feelings could never be reciprocated. Liquid Views projects the subject’s reflection outwards, entwining personal perception with public visibility.