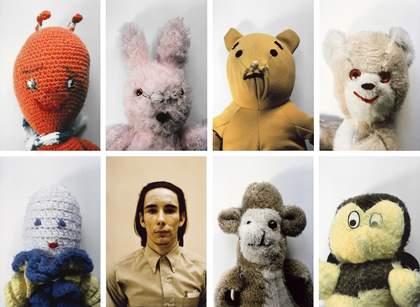

Brion Gysin with his Dreamachine, the Beat Hotel, Paris, c.1960

Brion Gysin © Galerie de France. Photo © Paris Musées, musée d’Art moderne, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / image ville de Paris

The American poet and interdisciplinary artist (and women’s undergarment designer) Hannah Weiner remarked in 1969, ‘The amount of information available has more than doubled since World War II. In the next ten years it will double again. How do we deal with it?’

Weiner’s observations and prescient question bring us back to an era of upheaval, the reverberations of which are still felt today. 1969, the year that boots were first set on the moon and the earliest version of the internet came about, was a mere 24 years after the conclusion of a cataclysmic global conflict. Whole cities had been destroyed overnight in firebombings, and in the blink of an eye by atomic weapons; genocide had been industrialised; empires were hurriedly formed and dismantled, resulting in unspeakable loss. The planetary nature of the war, its enormous and varied fronts, had made information and information technologies essential to the prosecution of national interests. By 1969, it was clear that these technologies were here to stay. They were infiltrating everyday existence at the most granular level. Meanwhile, information itself was taking on a historical life of its own: humans could no longer live without creating data, and the data that they generated begged to be used or, more ominously, ‘captured’.

Electric Dreams contemplates the long aftermath of the Second World War, its germinal information technologies and the advent of globalisation seen through the eyes and minds of innovative artists. That the exhibition begins with Atsuko Tanaka’s 1956 Electric Dress signals something important. This wearable artwork figures intimately the danger and potential inherent to the technologies of the postwar era. A dress that responded to its wearer’s control, Electric Dress was also uncomfortably hot, potentially deadly, and, at an estimated 60kg, quite heavy, as garments go. It additionally made its female wearer extraordinarily conspicuous – like the neon signs that illuminated Osaka’s bustling train station.

Kiyoji Otsuji

Tanaka Atsuko, Electric Dress, 2nd Gutai Exhibition 1956, printed 2012

© reserved

Electric Dress spoke to the pressures and possibilities of a transforming world. It made manifest a form of beauty that was at once threatening and playful, and it was an astonishing result of tinkering, which is to say, it made use of pre-existing technology for unforeseen ends. Reimagining by-products of 24/7 society, which we now call ‘light pollution’ and ‘information overload’, the dress was an ambivalent object.

Yet it ultimately suggested that the near future was bound to be an interesting, if unpredictable, time. The wearer of Electric Dress might even flourish. Certainly, she would experience joy.

This emphasis on the experiential nature of technology – that technology exists in a dynamic and often collaborative relationship with human users – is reflected in numerous pieces included in the show. The mathematician Norbert Wiener’s theory of cybernetics and the author and literary scholar Umberto Eco’s notion of the ‘open work’ both come into play. Wiener (no relation to Hannah Weiner) argued that the proliferation of information itself, along with interface-based technologies, required a theory of human society that emphasised feedback mechanisms. Eco, meanwhile, maintained that the implications and applications of a given technology are never exhaustively knowable, and this fact may be usefully transferred to artworks’ capacity to create meaning. This implies that the user/viewer must temporarily complete an ‘open’ work, rendering that work, in some sense, permanently contingent or incomplete. As, for example, with Brion Gysin’s Dreamachine, first developed in 1959: a given piece might not be representational or figurative in itself.

This is not to say that the work is abstract; rather, that the images and meanings to which it gives rise are determined by the individual making use of it. Those encountering the light pulses emitted by the Dreamachine enter a hypnogogic state and may perceive mandala-like patterns through their closed eyes. What this flickering, phantasmagoric visual and mental experience gives rise to for each viewer will, of course, be as unique as each viewer’s dreamlife.

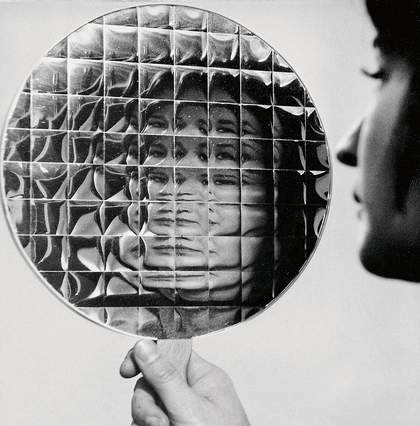

A woman inspects her reflection in one of Julio Le Parc’s six Double Mirrors 1966, made from painted wood and polystyrene foil

© Atelier Le Parc

The cybernetic self, which exists in dialogue with technology – both leading the machine and being led by it – is a self fundamentally in process. It is also a self that is ongoingly framed and reframed by its own attempts to view itself and to reflect on its own nature. Such attempts at self-voyeurism can be disruptive, illusory, or transformative, as Julio Le Parc’s 1966 piece, Double Mirrors, seems to suggest. It is worth noting that the grooves cut into the op-art-esque mirrors that Le Parc produced cause the viewer’s face to be mapped across various gridded planes. This artistic choice may inspire us to ponder possible distortions inherent to the contemporary digital image, as it is composed via the mapping of pixels across x and y coordinates.

Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss’s Liquid Views – Narcissus’ Digital Reflections 1992 is a different sort of trick mirror. Asking how moments of private reflection appear when broadcast to a wider audience, possibly by mass media, this interactive installation allows us to contemplate the point of view of the observer and that of the subject of the image simultaneously, bringing the virtual and the real – vertiginously – into the same visual frame so that they may be compared. This piece feels eerily prescient of the aesthetics of TikTok, for example, where the self is fodder for heavy-handed editing and looping. In this way, users of that application are doubly manifest, both as imagery themselves and as the highly visible manipulators of that imagery.

This question of the fictional nature of images, and how one should think about their alterability as well as their persuasiveness in an era of electronic and digital media, is strongly thematised across the show. The way images invoke or project forms of lost time is also of great significance to numerous artists represented here. Rita Keegan’s 1991 video, Rites of Passage, treats the image as a form of social fabric with the power to create unforeseen kinds of access to the past, thereby determining the future. Rites of Passage employs video as a collage medium, invoking the aesthetics of 19th- and early 20th-century album making by reactivating historical photographs to generate a palpable aesthetic lineage, in the relative absence of such materials in the canon of Western art.

Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss Examples of visitors’ performances of Liquid Views – Narcissus’ Digital Reflections 1992 at ZKM Centre for Art and Media, Karlsruhe

© Monika Fleischmann and Wolfgang Strauss

Nam June Paik and Jud Yalkut’s live television work of 1970, Video Commune (Beatles Beginning to End), similarly explores the relationship of so-called heritage media to electronic forms. Here, mixtures of footage of studio passersby, interspersed with fields of text and washes of colour, begin to resemble expressionist painting or dadaist art. Video becomes an improvisational, rather than automated medium, and the hand of the artist has a privileged role. Paik and Yalkut ask what it means to be a part of contemporary time and community in the age of the dominance of colour television. Can live television be an experimental art form? And Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun’s Inherent Rights, Vision Rights of 1992–3 constructs a longhouse in cyberspace to permit users to become virtually immersed in the world view of the Coast Salish (Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast), one that has been all but obliterated by colonialism. Each of these works heightens our perception of the social qualities of images. They inspire identification, shared feeling, and strategies of resistance, even as they are paradoxically available to the artist via commercial technologies.

The artist’s hand receives assistance from technology. Although even a simple stylus is an example of a technology, often the eternal inseparability of art and technology in human history is overlooked, or the presence of a more, or less, complex technological affordance is treated as devaluing the labour of a given artist, the artwork itself, or both. Alongside the works already discussed, Electric Dreams showcases a dizzying array of pieces in which an artist outsources the task of drawing to a machine – enhancing or constraining their own agency through this collaboration. Such works include pieces by Harold Cohen, Analívia Cordeiro, Samia Halaby, Tatsuo Miyajima, Sonia Landy Sheridan and Suzanne Treister, among others. It is worth underlining these artworks, because they so powerfully debate the nature of human agency and authorship in our time.

‘Q. ARE YOU DREAMING?’ reads a caption in one of Treister’s Fictional Videogame Stills 1991–2. Although the explosive proliferation of data and the ongoing rise of quantitative methods for comprehending the world would seem to offer a more rational, realistic, dreamless, or efficient way of living and allocating resources, even the most technophilic among us know that the much-celebrated ‘lifehack’ is mostly a fantasy. On a broader, societal level, popular computing and access to the internet have brought about new forms of unreason, hate, and emotionally driven ideologies that have resulted in horrific, real-world violence.

Samia Halaby

Land 1988

© The artist, courtesy Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut / Hamburg

These aspects of what technology has brought about since Hannah Weiner asked her question about data and how we would ‘deal with it’ are, to put things mildly, challenging. They provoke an ambivalent response from this writer.

Q. Are we dreaming? A. Yes, but not enough. Not as much as we could be. Not as much as we probably need to. Not as freely as we might wish. This said, Electric Dreams may reacquaint us with some of the dreams of the very recent past, whose implications and possibilities have yet to be either fully understood or, luckily for us, exhausted.

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern, 28 November 2024 – 1 June 2025.

Lucy Ives is an American author and critic who teaches at Brown University. Her most recent book is An Image of My Name Enters America: Essays.

Electric Dreams is presented in the Eyal Ofer Galleries. In Partnership with Gucci. With additional support from The Electric Dreams Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons. Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor. Curated by Val Ravaglia, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, and Odessa Warren, Assistant Curator, International Art (Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational), Tate Modern.