A print of Llyn-y-Cau, Cader Idris hanging in the front room of The Wynnstay, Machynlleth, 2024

Photo courtesy Mike Parker

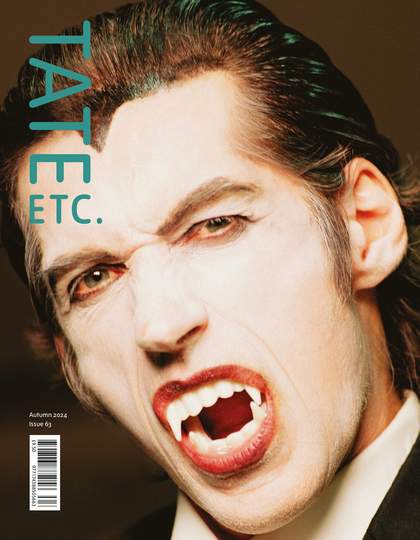

Since anyone can remember, a huge version of Richard Wilson’s Llyn-y-Cau, Cader Idris, exhibited in 1774, has hung in the front room of the Wynnstay, the oldest coaching inn in my hometown of Machynlleth in Wales. All the life of the place swirls around the painting’s jagged peak. The honour is twofold: Wilson was a child of Penegoes, the first village out of Machynlleth, and the mighty Cader (or Cadair) Idris is our mountain, the undisputed guvnor of our topography, geology and weather.

When I first moved to the area, I made a pilgrimage to sleep overnight, alone, on its summit. Not just any night either, but Nos Galan Gaeaf, or Halloween, when the otherworld is at its nearest and spirits storm from the deep. It was a predictably intense experience. Under a full moon, shining hard and silver on the racing clouds and cold, distant sea, I lost my mind that night, and came perilously close to losing my life.

In his rendition, Wilson caught a timeless landscape, but in a moment of flux. Prior to this, Welsh scenery was not well regarded in polite society. In A Tour Thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724–7), Daniel Defoe finds Wales ‘a Country looking so full of horror’ and wishes that he’d left it out of his itinerary altogether. That soon changed. Rapidly growing industrialisation and urbanisation meant a new appreciation of the wild places, while young bloods on their Grand Tours were cut off from the continent by the Napoleonic wars. From both directions, eyes turned towards our own mountainous regions. As a taste for the picturesque and the sublime roared through the ranks, Wales, Scotland and the Lakes became enthusiastic understudies for the Alps, the Dolomites and the Rhine.

Unintentionally, Wilson snagged the moment. His way of framing landscapes – muscular and moody, peppered with antiquities and under vast, lively skies – was learned during his seven years in Italy. Back home, he helped the style into vogue, and it is no overstatement to say that a direct thread runs from his work to that of subsequent landscapists such as Turner, John Crome and even Constable, all of whom acknowledged his influence. As was recognised by John Ruskin, Wilson is the true father of British landscape painting.

Richard Wilson

Llyn-y-Cau, Cader Idris (?exhibited 1774)

Tate

These artists laid the bedrock of a national self-image that still holds today, and not just in showing us the loveliness of our landscapes. Being bolted together with the same assiduity as its new factories and foundries was the nation-state of Great Britain, soon to be upgraded as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, together with its burgeoning empire. As always, art was appropriated by politics. The evident Italianate influence gave the new state intellectual and cultural ballast, flattering imperial England that it now wore the mantle of classical Rome.

That Wilson and many of his landscapes were Welsh only helped this mythmaking. With its castles and cataracts, bards, legends and mountains, Wales was presented as a paradise of primitive simplicity, the crucible of ancient Britain, with a fanciful backstory that was easily extrapolated into a kind of foundation saga for our soi-disant supremacy. Wales as the British ground zero is a whimsy still evident today, and one with which we still struggle.

Emphasis is all. Look no further than Wilson’s take on Llyn-y-Cau, Cader Idris. The mountain’s contours have been wildly exaggerated, enhancing its image as both a presumed extinct volcano and a wilderness, but also as a cauldron of legend. Rather than a straight portrait, the picture gives us an evocation of the mountain, of its light and atmosphere, and hints at the sense of awe that it provokes within us, both on canvas and in its thrilling corporeality. Through multiple engravings, the painting became one of Wilson’s most loved and enduring images, which reflects the popularity of the peak itself. Though just the 19th-highest mountain in Wales, Cader Idris is second only to Yr Wyddfa (Snowdon) in public renown.

My experience on the mountain that Halloween night taught me things about respect and perspective that I still check in with daily, nearly a quarter of a century later. And in the bar at the Wynnstay, before sinking a pint or ordering dinner, I nod each and every time to Llyn-y-Cau, Cader Idris, out of respect, out of admiration, out of love – but most of all out of raw, bloody terror.

Llyn-y-Cau, Cader Idris was presented by Sir Edward Marsh in 1945 and is on display in The Exhibition Age at Tate Britain.

Mike Parker is a writer and broadcaster based in Mid Wales.