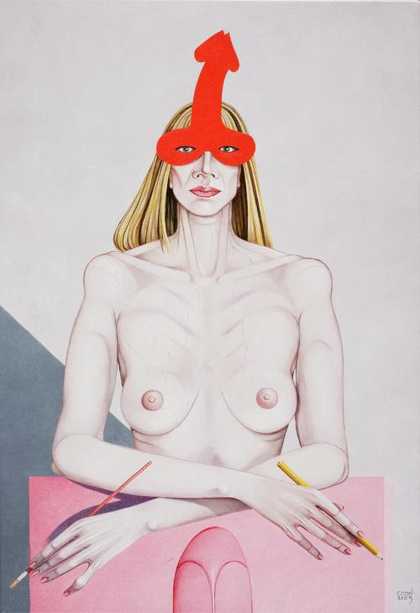

Allison Katz

Portrait of the artist as a young girl(s) (2022)

Tate

I don’t remember the photographer who posed me for the picture on which this painting is based. She was a friend of my grandmother, Edna, and I never saw her again. But something magical must have passed between us: I can see the curiosity and trust in my eyes, an early experience of complicity in the making of an image, modelling something for her I didn’t know I embodied. This wasn’t a commissioned portrait or a family photo – there were no framed copies hanging at home – so I can only assume it was for her own practice, but I’ll never know. There are several images from that session. In some, I wear a woman’s red hat with a nervous look; in another, a string of pearls and a surly, focused gaze. We were playing.

I found this photo among Edna’s things some 20 years ago. She is now 94, and her apartment is constantly turning up treasures. I must have absentmindedly scanned the photo, because it was saved on my computer in a folder of random images that I keep while considering why, or how, they might figure into my work. That is generally how I decide to paint something: an image, idea or word speaks to me, but I wait for a series of synchronicities to push that drive into action. An internal movement mixes with something outside my control.

One day I was going through this folder with a friend, and he had a eureka moment: ‘There’s your Venice painting!’ At the time, I had been trying to decide on a subject for The Milk of Dreams, the main exhibition at the 2022 Venice Biennale. I knew only that I wanted to paint Venice itself, since it’s the ultimate subject of self-reflection: a city built on water, inspiring centuries of artists.

At once, I also saw my striking resemblance in the photo to a character in the thriller Don’t Look Now (1973). I’m usually too scared to watch horror films and this happens to be the only one I have ever seen – in graduate school when trying to impress a boyfriend, who had said it was ‘seminal’. In Daphne du Maurier’s original ghost story, upon which it’s based, the girl has dark hair, didn’t drown, and it’s actually her mother who wears a crimson coat. But the director Nicolas Roeg made water and red the motifs of the film and cast a blonde girl to play Christine, the grieving couple’s young daughter. Roeg was said to be influenced by a chapter in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (1913–27) set in Venice, in which the protagonist sees a figure in a red coat, which painfully reminds him of his lost love. Like most indelible images that we have come to think of as original, it is a composite of multiple sources.

The young girl is at the centre of the history of painting: think Velázquez’s Las Meninas 1656 onwards. She is often shown wearing red. That’s the folklore of the colour: transitions, menstruation, sexuality, love, vengeance, passion. Life and death. On the cusp. I’ve heard a lot of people casually refer to this painting as the one about ‘Little Red Riding Hood’. I can understand why. I started this work by loading my brush with pure, cadmium-red oil paint. I knew the power of this pigment would determine everything.

Painting Portrait of the artist as a young girl(s) made me reflect on ideas of innocence and experience, and the discipline it takes to reconnect with the free spirit inside that young girl. I felt like I was meeting the girl I was back then, and I was taken aback by how uncanny I found the experience; wordless and elemental, a reparation, a befriending, maybe even a mothering, a softening towards all the mysteries and misunderstandings of childhood that still cause unconscious hurt and irrational patterns so far into adulthood. It was important to scale the figure up to life size, to leave aside any nostalgia associated with the photograph, to feel as if the figures are in the room – especially as they glimmer in and out of focus.

I didn’t want to call this a ‘self-portrait’, because I was meeting this girl again, and while she is me, there were many forces at play in bringing this ver- sion of myself to the canvas. I was also thinking about James Joyce’s novel A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916). I liked this reference to an artist’s growth to maturity, but I wanted to offer a counterpoint to a single trajectory, to emphasise the multitude inside the girl, her endless guises and ways of becoming, and how all of her selves are still within my view, transmitting the freedom to stay open, fragmented, spirited.

Portrait of the artist as a young girl(s) purchased with funds provided by Simon Nixon and family in 2022.

Allison Katz is an artist from Montreal who lives and works in London.