Mike Kelley Ahh...Youth! 1991/2008 © Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY & DACS, London.

Pitiful stuffed animals seemingly abducted from an impoverished child; crude Xeroxed workplace cartoons painted on the walls of a replica of an office designed by the architect Frank Gehry; the weirdly heartbreaking and wretched spectacle of an actor dressed as Superman, reciting passages from The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath on a dark soundstage; a high-school talent show rendered as an apocalyptic musical, complete with a hymn to Gene Simmons, ‘The Demon’ from Kiss. These are just a few works from the wildly mutating oeuvre of the late Mike Kelley.

And then there is the interstellar noise rock he conjured up with his band Destroy All Monsters or his freaky anthropological Wunderkammer exhibition The Uncanny (first mounted at Sonsbeek outdoor sculpture exhibition in the Netherlands in 1993, and later restaged at Tate Liverpool in 2004); or Foul Perfection, his collection of essays on other people’s art and aesthetics; or his many collaborations, including his video Heidi 1992, created with artist Paul McCarthy, which would become part of a rancid fairytale installation. These multiple bodies of madly influential work were made across a 40-year career, but what was the diabolical impulse animating it all?

‘Art’, Kelley said in an interview filmed in 2004, ‘is about fucking things up for the pure pleasure of fucking things up.’1 Now, what might ‘fucking things up’ entail? Caustic commentary on the art world’s short-lived hysterical vogues for this concept or that approach? Trollish provocation? Daring explorations of different kinds of ugliness? Totally. But also fucking things up for himself, again and again, as a kind of anarchic methodology – never settling into a handsome brand but instead compulsively shapeshifting.

Mike Kelley

Reconstructed History: The Empire State Building 1989

© Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY / DACS, London

The allusive density of Kelley’s work can be discombobulating: Bruce Nauman, The Twilight Zone, Arte Povera, Dada, Salvador Dalí. And tons more... Sometimes the surface of his work is cute (aw, stuffed animals!); sometimes it’s obnoxious – the Reconstructed History 1989 series looks like pages from a high-school textbook defaced by a goofy stoner: via ballpoint pen, the Empire State Building becomes a dick endowed with balls and spurting cum.

Kelley is troublesome and hilarious (I don’t think anybody in art history has been funnier than Mike Kelley). His art is very American, just as much as it can be sinister or deeply sad. But, for all this mutation, it’s a remarkably cohesive body of work. As he put it (seemingly) straightforwardly in a 1999 interview: ‘I play games.’

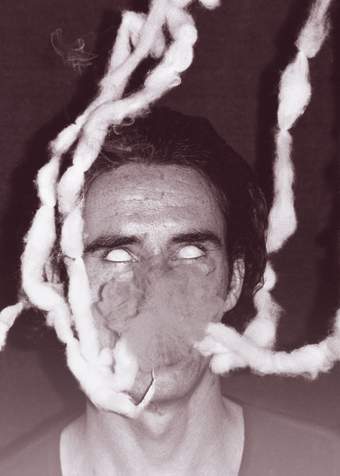

Mike Kelley

Ectoplasm Photograph 10 1978/2009

© Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY / DACS, London

This trickster impulse oozes from Kelley’s early work The Poltergeist 1979: behold, the skinny, young artist as a vessel for evil spirits! Self-portrait as a demon! Ectoplasm flows from his mouth and eyes! Except, it’s cotton wool. Kelley is making mischief with the tradition of 19th-century spiritualist photographs, which manufactured ‘evidence’ of such otherworldly encounters, to his own subversive ends. It’s a counterfeit, snotty, punk yet ghoulish, wilfully inauthentic. He may be pranking our faith in the medium (a rather spooky word, no?) of photography and playing with his body as a vessel during the heyday of performance art, but there’s also that eternal horror-movie vibe gushing out, too... In an interview recorded at Hollywood’s Amoeba Music record store in 2010, he said he was ‘always on a horror binge’. Perfect. Horror is the genre where we go to find out what’s really going on inside: all our gore and trauma and hideousness festively unleashed.

Mike Kelley

The Prenatal Mutual Recognition of Betty and Barney Hill 1995

© Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY / DACS, London. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

Given that Tate’s sprawling retrospective is entitled Ghost and Spirit, what sort of spookiness, what kind of haunting is afoot within Kelley’s work? One way to think about his oeuvre might be as an experience of hauntedness – by Catholicism, by American pop culture and its diabolical underground double, by psychoanalysis. He is the poltergeist haunting the house of art history, running amok, terrorising good taste, moving from form to form, host body to host body in order to explode it. He makes you question if whatever he’s puked up for you is even art at all, which is what always happens with the best art. His purposes are satirical and anarchic, revelling in the return of the repressed: the trashy and the grotesque, the blue collar, the subcultural and the ‘anti-aesthetic’. 2

When he made More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid 1987, which consists of raggedy, stuffed animals sewn together to form an epic tapestry, Kelley said he was kissing off Jeff Koons who made his first ‘Patrick Bateman but chill’ imprint on the New York art world by exhibiting genuine consumer goods: vacuum cleaners, plastic flowers, basketballs. Slick, exquisite, and, according to Koons, deeply spiritual.

Mike Kelley

More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid and The Wages of Sin 1987

© Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY / DACS, London. Photo © 2024 Douglas M. Parker Studio

The little creatures in More Love Hours are not that. Thriftstore zombies, rejected peace offerings, gifts for ghosts – they’re chewed up, abandoned. As film director, artist and esteemed filth elder, John Waters wisely observed, wherever they appeared, Kelley’s stuffed animals made ‘a museum or gallery [take] on the appearance of a coroner’s office displaying the corpses of toys after an airplane crashed into Santa’s sleigh mid-flight on Christmas Eve.’ The vibe could be cute but isn’t: More Love Hours is more David Cronenberg – a seething mass of rotting flesh. If I step closer, I just see these poor critters breeding feelings of guilt and shame.3

Kelley was slipping on his Duchamp mask and parodying the twisted economics of the readymade, hyped into overdrive by Reaganomics: ‘Oh, even this loathsome artefact can be enchanted and rendered valuable through the magical powers of the artist’s hand!’ But there’s something more... pathological going on. He was getting into the wickedly masochistic rituals of family life. ‘Say you give somebody this piece-of-shit thing’, he explained in BOMB magazine, ‘[they] can’t say it’s a piece of shit – it’s all totally repressed. [They’ve] got to say, “Oh, that’s wonderful!”’

Nobody in the critical establishment got More Love Hours: the tapestry was read in an Oprah-esque way as an oblique confession of childhood trauma, accidentally providing Kelley with the bedrock for all of his future work. Daddy issues do leave a kind of, uh, residue on the tapestry, though. As Kelley relates in his 1991 essay, ‘Some Aesthetic High Points’, his father pressured him as a kid ‘“to act more normal” ... To spite him I took up sewing, not because I had any interest in it but just to piss him off.’

Mike Kelley

Educational Complex 1995

© Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY / DACS, London. Photo: Göran Örtegren

Kelley’s childhood home is among the buildings reconstructed in Educational Complex 1995 (We’ll return to that house: Kelley’s work is always about stuff coming back...) A creepy, tabletop architectural model of everywhere Kelley was educated – home, elementary school, the University of Michigan, CalArts (California Institute of the Arts) – Educational Complex is a reckoning with several different phantoms. Let’s do a school text-book-style breakdown:

A) Abuse. Following all the dark conjecture about Kelley’s childhood caused by interpretations of More Love Hours, he slyly decided he’d indeed make work about his version of ‘abuse’: the traumatic ordeal of being educated in art, which meant having to repress all kinds of urges, ugliness and psychic detritus. In a 2000 interview with the writer Dennis Cooper, he pointed out, ‘We’re living in a period in which victim culture and trauma [are said to be] the motivation behind every action.’4

B) Memory itself. He only rebuilt what he could remember, from what he called ‘a vast undifferentiated swamp’ of childhood and adolescent recollection. The results were architecturally weird, haphazard, incomplete. Post his Educational Complex, Kelley was always investigating memory: repressed memory syndrome (the ‘recovery’ of bogus memories relating to alien abduction, Satanic rituals, child abuse or a combination thereof – then all the rage in pop psychology and on talk shows like Jerry Springer and Geraldo); his own childhood/adolescent memories; the erratic habits of memory in general, and the impossibility of ever accurately reconstructing them.5

C) Failure. If Samuel Beckett were alive, he’d tell you that all of Kelley’s work is actually haunted by the spectre of failure: your memory betrays you, the ectoplasm is fake, Superman is depressed.6

Mike Kelley

Day Is Done (Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions #2–#32) 2005–6

© Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY / DACS, London. Photo: Ericka Beckman

The stuff within this eerie swamp (childhood trauma, education, memory) would soon mutate into Day Is Done (Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions #2–#32) 2005–6. Maybe Kelley’s masterpiece, it is bonkers, an entity unto itself: a nearly three-hour movie musical extravaganza reconstructing and riffing on archival photographs of high school pageantry – candle-lighting ceremonies, Hee Haw-style hoedowns, Halloween anarchy. The cast includes singing vampires, neo-Nazi rappers, an extremely horny devil, a pantomime donkey, and Kabuki-faced dancers. Roll up, roll up! It’s vast while simultaneously a microcosm of his entire oeuvre: music, the Catholic boy preoccupation with ritual, demented confabulation based on (false?) memories, the traumatic aspects of education, the horror thing, dressing up games.

The movie was originally shown within an insane P.T. Barnum-on-amphetamines funhouse installation. Multiple screens blaring at once, neon signs flashing, sculptures underfoot, and photographs and drawings scattered everywhere. Careful you don’t step on the plush snake! The show was debuting at Gagosian gallery in New York and, as Kelley told Artforum at the time, he was thinking of Broadway.

Mike Kelley

Day Is Done, installation view at Gagosian, New York, 2005

© Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY / DACS, London. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

In its triple XL scale and ambition, Day Is Done is also holding that funhouse mirror up to the art world of the time, high on the filthy lucre of the boom years, so cunning and slick in its ability to ape the production values of mainstream entertainment that sometimes the two could not be told apart. I’m not saying that Kelley was trying to ‘beat’ The Cremaster Cycle 1994–2002 by Matthew Barney, but it’s fun to think of them in battle, like Godzilla and King Kong.

In the wake of all that pandemonium, cue the inevitable comedown. The Kandors 1999– 2011 sculptures draw on the tragic mythology surrounding Superman: Kandor is the city from his exploded home planet of Krypton, which survives only in shrunken form within a bell jar. The Man of Tomorrow broods eternally on how to restore it to its former splendour from within the icy caverns of his Fortress of Solitude. As far back as Educational Complex, Kandor was on Kelley’s mind. He saw a spooky continuity between the two, manifestations of ‘the past that can never be recovered, the home that can never be revisited’. The Kandor works are goosebumped by a certain depressive chill: they’re dreamy, psychedelic and sad, the shattered pieces of a sci-fi cathedral emitting a sinister glow. ‘There’s a lot of tenderness in Mike’s work...’, Bruce Hainley told me, ‘sadness, too.’

Mike Kelley

Kandors Full Set 2005–9 (detail)

© Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY / DACS, London. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

From outer space and back to the suburbs, the instability of home is also a big deal in Mobile Homestead 2005–13, Kelley’s final (indeed, post-humously completed) work. A replica of Kelley’s childhood home from Westland, Michigan, it’s a suburban clap-board house designed to be used as a community gallery on the grounds of the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD). The façade of the home is detachable and can be towed on the back of a truck to operate as (in part) a roving public sculpture that also fulfills public services: exhibition space, studio, outreach headquarters. ‘How nice, how civic-minded of Mike, how curiously... defanged’, you might think. Have you learned nothing! Mobile Homestead is a haunted house, a mutant, a sly provocation. In a statement upon its unveiling, Kelley wrote, ‘it is simultaneously geared toward community service and anti-social private subcultural activities.’ Yup, rival urges, the id and superego: the ground floor is dedicated to the public stuff like exhibitions while the subterranean basement is a diabolical lair where local artists can make work.

Mike Kelley

Mobile Homestead at the Kay Beard Building, Westland, Michigan, 2010

© Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY / DACS, London. Photo: Corine Vermeulen

Kelley always liked basements. Of course he did: in psychoanalytic interpretations of architecture (and/or architectural interpretations of the psyche), the basement is where the mind’s darker urges lurk, where that which is nasty, anarchic, disruptive and wicked can be explored at will: in other words, the good shit, if you’re Mike Kelley.

The fact that Mobile Homestead is a moving installation is deep, an illustration of Kelley’s own relentless activity. Don’t discount the sheer alien disturbance that comes with the house’s journey from place to place – this mid-century Michigan house’s arrival was once an uncanny apparition in the middle of LA’s Skid Row. Upon its Detroit debut, Mobile Homestead undertook its own psychogeographic journey through the city, charted by Kelley, heading from MOCAD and stopping at sites symbolically significant to him before ending up alongside its double, which Kelley slyly dubbed ‘the mothership’: his childhood home in Westland.

Mobile Homestead is an attempt at time travel, doomed to failure, naturally, but still magic, in which Kelley revisits the wreckage of the past yet again – ‘the past’, yes, ‘which can never be recovered’. The melancholy metastasises to incorporate Detroit, too: it’s a personal history of an industrial city in decline, a city undead. Hard not to see, in its circularity, as something like a farewell: it ends where it all began. Kelley worked on the piece up until the last days of his life.

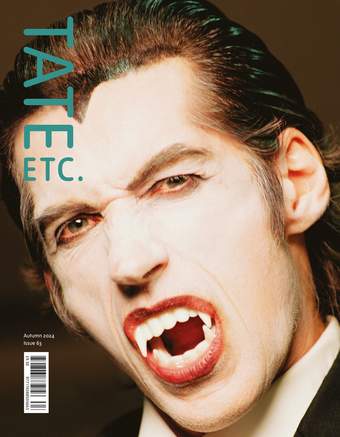

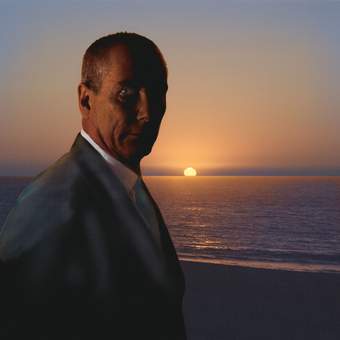

Photograph of Mike Kelley as used on the cover of the exhibition catalogue Day Is Done (2005)

© Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / VAGA at ARS, NY / DACS, London. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen

I think his spectre might puke on me and call this ridiculous but, since the retrospective is called Ghost and Spirit, I will say this: All the great artists are undead – they have a shapeshifting afterlife; they keep haunting us. Mike Kelley does that, too, in so many ways. It would be too easy to say that everybody owes him a debt, but they do: Jamian Juliano-Villani’s brain-melting cursed image paintings made from pop trash, Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin’s haunted barn installation, Whether Line 2019, Mark Leckey’s alignment of working-class and occult energies, Precious Okoyomon’s cute but ogreish stuffed bears... No way am I going to fade out saying ‘rest in peace’: his ghost is still here. He’s still fucking things up.

Thanks to Jim Shaw and Bruce Hainley.

Mike Kelley: Ghost and Spirit, Tate Modern, 3 October 2024 – 9 March 2025.

Charlie Fox is a writer and artist who lives in London. Flowers of Romance, a group exhibition he has curated at Lodovico Corsini in Brussels, runs until 21 December.

Supported by The Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts, The Mike Kelley Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons. Exhibition organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with Bourse de Commerce, Paris, K21, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf and Moderna Museet, Stockholm. Curated by Catherine Wood, Director of Programme, Fiontán Moran, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, and Beatriz Garcia-Velasco, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern.