Steel pans surround Alvaro Barrington’s sculpture of Samantha dancing at Notting Hill Carnival, caught in the moment. The base of the sculpture makes reference to ocean waves, with steel pans tuned specifically for the commission. Visitors are invited to play the drums delicately with their fingertips

© Alvaro Barrington. Photo © Serena Brown

1. On Metal

GRACE resounds everywhere: rain and music amplified by a tin roof, sticks beating steel drums, aluminium shutters clicking a rhythm. Metal is often admired for a colder and more efficient grace, but we can experience this material differently. When love is reimagined repeatedly against the cruellest circumstances of capitalism, it becomes malleable and resonates with a state of grace. In the same way, metal is changed; it sounds warmly.

GRACE, Alvaro Barrington’s Tate Britain Commission for 2024, rings with the rich and painful experiences that enabled him to become an artist. Barrington was born in Venezuela to Haitian and Grenadian parents. His grandmother Frederica looked after him in Grenada so that his mother Emelda could work in New York (caring for other people’s children) until he joined her in Brooklyn, aged eight. He moved to London in 2015 to study painting at the Slade School of Fine Art.

Across three places (Grenada, New York, London) and three generations of women (Frederica, Emelda, and sister Samantha) Barrington enfolds us into the love, grief and bacchanal of his own personal Caribbean diaspora. The commission begins within an embodiment of Frederica’s home – roof, wall, windows, quilts and lights all rich with memories. The work continues through crowds of paintings depicting carnival’s jubilance, centred by a resplendent sculpture of Samantha. The conclusion is an evocation of Emelda’s love and maternal fears, in the pews and stained glass of a church and a sombre, barricaded street corner scene. GRACE honours the labours of love of the women who raised him and his communities, sounding and re-sounding unsung people and their breathtaking resourcefulness.

The routes of Barrington’s own Atlantic triangulation were carved by a long history of the colonial extraction of people and resources. Enormous ancestral as well as personal loss accompanies these journeys. Barrington’s commission tells a story of Black culture: a matrilineal allegory of the gestation of Blackness in the Middle Passage – the forced journey by millions of African people across the Atlantic to slave labour in the Americas, often the Caribbean – maturing to Blackness as the mother of culture (globally influential, admired, copied, appropriated). Black women’s love and work are entwined in his ode, emphasising how his communities showed up for each other, loving their children with ingenuity. He often says that this early experience is what made him a painter.

Later, his study of painting brought him to Britain, which ultimately led to the commissioning of GRACE within the national home of British art. He emphasises that, for him, painting is ‘a communal act in a sea of other creative ways of making; even if I’m the only one actually “painting”, it’s framed within communities that I feel a part of, not isolated from, and that includes carnival community’. In one sense, every fingernail, seat or window in GRACE is a painting or a frame for one. In another way, painting is a small part of an expansive, collaborative cross-arts celebration.

Barrington explained to Hannah Marsh, assistant curator on the project, how the spaces within the gallery can relate to the Middle Passage and the creation of subcultures: ‘I was interested in the idea of the gallery as a passage, and the commission opening up [and connecting] different parts of the building. There are all these histories that you can see in different parts of Tate. You have this passage, this journey, that has created so many different cultures, subcultures. Music is a driving force of so many different subcultures. Punk, disco, hip-hop, dancehall, reggae. And most of these forms were invented by Black people – there must have been something within that passage that created this innovation, the need for all these different subcultures – and how those subcultures manifested themselves in the world. The Caribbean, expanding globally.’

Culture, Britain and the Caribbean have a complex relationship. The first prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago, following independence from colonial rule in 1962, was the historian Eric Williams. His 1944 book Capitalism and Slavery asserted that the accumulated profits from slavery financed the industrial revolution in England. Despite robust research showing that British compensation to slave owners after abolition enabled further widespread investment and influence, our business and trade secretary Kemi Badenoch insisted in April this year that the ‘UK’s wealth isn’t from white privilege and colonialism’. A year earlier, our prime minister Rishi Sunak refused to apologise for the UK’s role in the slave trade, or pledge any reparations. It is hard to stomach this rhetoric standing within Tate, an institution built with wealth made in the Caribbean on plantations established under slavery. It takes untold grace to help create a different welcome within this kind of institutional setting, particularly against a backdrop of such political denial.

Barrington has created a series of embroidered postcards, which have been placed inside plastic pillow slips, stitched together and laid on top of rattan and bamboo sofas. This furniture reflects the artist’s interest in collage, but also honours the sewing techniques and labours of his aunties, as well as the safety and comfort the artist felt in his grandmother’s home

© Alvaro Barrington. Photo © Tate (Oliver Cowling)

2. From South to North

The Tate Britain Commission is the largest regular presentation of art by one artist at Tate Britain. In theory, with free entry to the central thoroughfare of the building, all are welcome; the reality isn’t so neat. Like many museums, and particularly those with the architectural grandeur and reputation of Tate Britain, it is not easy to let everyone know that this art is theirs – the intimidating interiors, the bag searches, attendants, ticketing. As museum professionals and custodians of a national collection and public building, how we change who feels welcome is one of the biggest issues we grapple with.

The Duveen Galleries run roughly from the south to the north of Tate Britain and are often described as an interconnecting spine for both the institution, and the histories of 500 years of British art it carries, a period that also covers the duration of the British Empire. There are many different points of entry and departure, many areas that people have not always felt comfortable accessing or remaining within. The north/south orientation is a geography that I consider relevant here in relation to how differently we might each approach Tate Britain. Mapping is often a colonial endeavour, but in response to the global reaches of colonisation, it can also align vastly different experiences of racism across the Global South, including Latin America, the Caribbean and Africa, in relation to Barrington’s diasporic experience and heritage.

Barrington’s GRACE fills the Duveens with a warmer welcome than any we could have conceived of when the commission was agreed. Deeply aware of the exclusions of any place ‘with a door’, as Barrington has said, his installation enfolds any who enter the space within a clear invitation to love and honour, despite Tate’s history and institutional weight.

If you enter through the south Duveen, from the river Thames, a few minutes from the Houses of Parliament (or Palace of Westminster), up the grand steps and through the bright rotunda, you enter the protective grace of Frederica, Alvaro’s grandmother. The vast, vaulted room is hushed by a corrugated roof that shelters us all within an evocation of Frederica’s small home on the island of Grenada during the constancy of the rainy season. Sound washes over us – rain all day, steel pan, new tracks too – a preparatory rite in the care we must take with the graces that follow. Peace comes. The beat of rain on a tin roof is described by so many from tropical places as the sound of a good night’s sleep.

Curved rattan and bamboo sofas seat us in a maternal rib cage, all skilfully bound together by hair braiders. The plastic that covers so much upholstery in the homes of displaced people transfigures the barriers of a museum’s preservation of art objects into Frederica’s safety. You are the precious thing within its skin. Barrington’s mother sent the sofa ‘from foreign’, bought with the money made living and working abroad. He is clear that the plastic was not to protect the furniture from the children who had run inside from the storm, however, but to slow time itself: ‘[Frederica] was protecting my mom coming home; “we’re right here like you never left”.’ The labours of love.

Painted pillow slips are samples of this time, patch- worked together with embroidered postcards, remixed small monuments ‘to the people you don’t see who built the infrastructure, intimate because the workers are intimate to me’. We are contained within two L-shaped corners of Frederica’s home; the glimpses through the window include ‘yarn painting’ landscapes: ‘one of the reasons I sew these yarn paintings is it points to the labour of my aunts – how they, and the general community of women I look at, understood painting’.

The north Duveen can be entered more quietly from the side, and the space more starkly evokes a cathedral as you turn in and face the permanent materiality of a stained-glass window within the fleeting setting of a temporary art commission. As Barrington has said: ‘What’s interesting about the stained glass is, even though it’s glass, it’s based on the yarn textile work and conjures up these conversations about these women’s labours... All of the women turned to church as a way to let go of a system they felt powerless to confront. They knew collectively they had no power but had each other; so we had to grow up in church, where our mommas were together’.

In the far north of the gallery, a New York corner kiosk is encircled by barriers, exaggerated museum methods this time representing danger – sometimes deadly – or incarceration at the hands of the state. The worst that could happen has happened, in the infamous 1980s New York corner raids: mass arrests targeting Black communities. Barrington’s mother Emelda’s grace fears her child going out to the corner store in a world where Black children are not treated as children; the corners where Black lives are treated cheaply are memorialised here. Church pews allow us to pause and contemplate both the window and the corner. Plastic pillow slips evoke devotion and craft.

‘The first moment is the last moment. The bench. My grandma intermixing from beginning to end’.

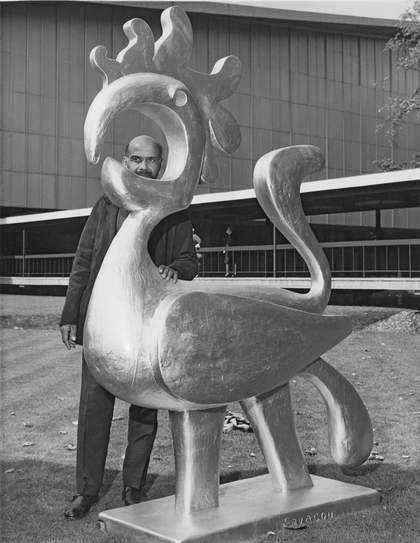

At the heart of Tate Britain, an octagonal space joins north and south galleries. Here we find a monumental sculpture of Alvaro Barrington’s sister Samantha, who has lent him her likeness from a moment of dancing at Notting Hill Carnival. The jewellery, nails and costume and a huge communal drum proffer Caribbean carnival’s respect for women’s bodily agency in public, ‘where we all understand that is her space’, a respect that art history and its institutions can learn much from. We are all invited to be participants in this protective culture. And so the carnival begins.

The sculpture of Samantha is adorned in jewellery and clothing made by different artists. Samantha’s bikini, which we see a detail of here, was made by designers Dynasty and Soull Ogun (L’Enchanteur)

© Alvaro Barrington. Photo © Tate (Oliver Cowling)

3. Everybody Jouvay

In Caribbean carnival, the new day is awaited from midnight on Dimanche Gras (Carnival Sunday) and greeted with noise, paint and mud. This dawning is known as Jouvay morning, from the French patois ‘jour ouvert’. Historic accounts from Martinique and Trinidad record people repeating ‘jour ouvert, jour p’oncore ouvert’ (the day is breaking, the day is not yet broken). On 1 August 1838, enslaved people across the British Empire in the Caribbean were officially emancipated. Only shortly afterwards, in the 1840s, the colonial administration tacked the celebration onto carnival. The Trinidadian novelist Earl Lovelace looked back to Carnival Sunday-night fêtes, ‘green bush held aloft, old, young, everybody out to Jouvay’, with the observation that they did not realise they were also celebrating emancipation.

Mas boys – blue devils, every type of sailor, drag-ons, midnight robbers, fancy Indians, moko jumbies (towering protectors of the people who were said to have accompanied them, walking high across the waves of the Middle Passage) – saw in the new day with soucouyants (vampiric hags) and La Diablesse (diabolical seductress): boys, mothers, everybody Jouvay. This was accompanied by the beating sound of resistance. Steel pan finds its roots in burning sugar cane, bamboo stick fighting, then the resourcefulness of pots and pans, hub caps, biscuit tins and steel drums (once containing the bitumen from the tar pits of central Trinidad, which sealed Sir Walter Raleigh’s boat and would later pave the world). The drums were tuned and arranged. So often these sounds on metal are diminished to a holiday ambiance by a popular imagining of the Caribbean as a languorous paradise for Western consumption. Like the appropriation of the Hawaiian shirt and the palm tree, the steel pan has become short-hand for leisure – for not working – a leisure haunted by the question of who plays the tune, serves the drinks, changes the sheets, looks after the children.

As a girl, then woman, and eventually a mother in another part of the Caribbean diaspora in London, I learned from my grandma Umilta that one way to cheer a fractious baby was to dance and repeat, child on hip, ‘a-ping pang pang, pi-ping pang; a-ping pang ping, pi-ping ping’. It was an imitation of the sound of steel pan, the only percussion instrument developed in the 20th century, one stemming from a long history of noisy resistance and revelry ‘on the road’ of the Trinidad carnival. The steel pan is the sound of public, collective, rhythmic, melodious noise, but one that is also refracted through the diasporic molecule of my family life. The calypso lullaby Brown Skin Girl (which continues: ‘stay home and mind baby’) can be heard through the rain on Frederica’s roof – the musician Olukemi Lijadu also thinking of her Caribbean grandmother’s voice.

These are intimate things to share, coming from private and protected experiences as a member of the second generation. My cousins and siblings delighted in the rowdy faraway fragment of the steel pan sung for us, but knew, too, the losses and longing it voiced, turned inwards to the safety of family in an inhospitable Britain. This kind of interplay between public and private is integral to Barrington’s navigation of the path through a museum like Tate Britain. We ask if the Duveen Galleries can be a safe road.

GRACE honours Black culture, its most invisible labours celebrated with sound and pigment. It can teach us so much about transforming the barriers of exclusion into gestures of love and respect.

Tate Britain Commission: Alvaro Barrington: GRACE at Tate Britain until 26 January 2025.

Supported by Bottega Veneta and The Bukhman Family Foundation. With additional support from the Tate Britain Commission: Alvaro Barrington Supporters Circle and Tate Americas Foundation. Curated by Dominique Heyse-Moore, Senior Curator Contemporary British Art; Hannah Marsh, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art; Sade Sarumi, Curatorial Assistant; and Chloe Hodge, Project Curator and Manager, Commissions.