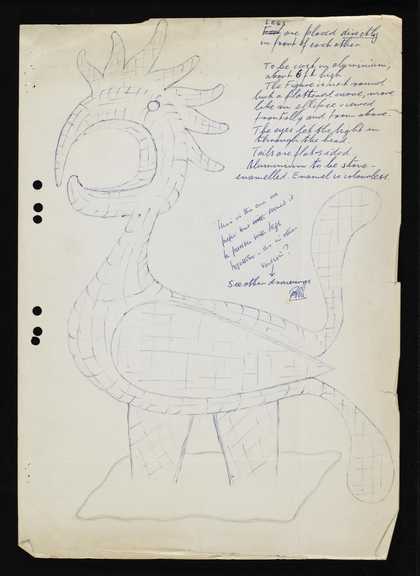

Ronald Moody standing beside his public sculpture Savacou on the lawn of the Commonwealth Institute, London on 21 August 1964, where it was installed for a month before embarking on its final journey to Kingston, Jamaica

© The Ronald Moody Trust. Photo by George W. Hales/Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The modernist sculptor Ronald Moody (1900–1984) is perhaps best known for his intuitive and animated use of wood grain in direct carvings such as Johanaan 1936, Midonz 1937, The Onlooker 1958–62 and Hope 1966–7, all now in Tate’s collection. However, between the mid-1950s and late 1960s, he produced a series of striking bird sculptures in plaster, oak, concrete and fibreglass that reflected his wide-ranging interests and technical abilities. Orchid Bird 1968, for example, was inspired by his observations of orchid flowers at Kew Gardens, while many others stemmed from his longstanding appreciation of ancient civilisations, such as Egypt.

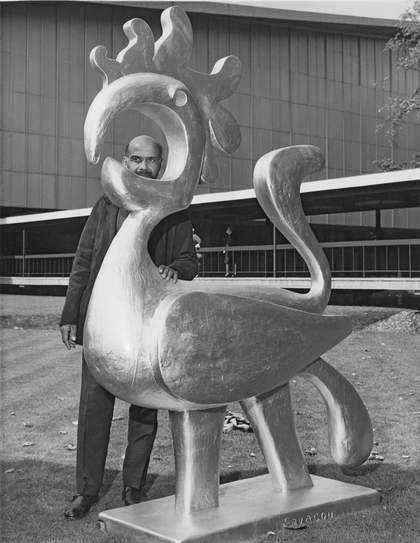

In 1963, Moody was approached by the Epidemiological Research Unit in South Wales to create an outdoor sculpture for their sister unit on the University of the West Indies’ Mona Campus in Kingston, Jamaica. Savacou 1964 would be Moody’s only public commissioned artwork, and was, as he put it, a visualisation of a ‘proud, invincible and to some extent arrogant’ Carib celestial deity, inspired by his interest in Taino cosmology. As Moody would explain in a letter to his commissioners: ‘To a Carib, Savacou, who became a bird and later a star, was attributed control over thunder and the strong winds.’ Standing approximately eight feet high, this sleek yet plump, shiny, prideful, non-binary bird continues to preside over its dominion to this day.

When Moody travelled to Jamaica for the installation, it was the first time he had returned to his birth country since settling in Britain in 1923. He had grown up near Knutsford Park, just outside Kingston, and his tacit understanding of the local landscape informed his choice of subject. In a BBC documentary broadcast in 1953, he nostalgically recalled a childhood of hill climbing, surf-bathing at the Palisadoes in the scorching Jamaican sun and gazing at the beautiful Blue Mountains from his bedroom window. He likened the mountains that run the length of the island to the ‘backbone of a prehistoric animal’. Moody was enchanted by the ‘play of light’ on them and the way ‘the floating blue would suddenly change to azure flecked with gold’, as quickly turning to ‘a deep and ominous blue with angry clouds that told of a sudden, heavy downpour’.

Ronald Moody

Orchid Bird 1968

© The Ronald Moody Trust. Photo: Philip Connor

A sketch of Savacou by Ronald Moody in Tate Archive with handwritten notes about the design, 1963

© The Ronald Moody Trust. Photo © Tate / TGA 956/2/2/13/140

Moody’s decision to cast his sculpture in lightweight, durable aluminium primarily reflected the need for a material that would ‘successfully withstand the rain, heat and wind of Jamaica’. Aluminium, however, also symbolised 20th-century modernity, as well as newly independent Jamaica’s position as a leader in the growing industry for mining the aluminium ore, bauxite. To contemporary viewers, it might connect to discussions around the global political economy of natural resource extraction, and the cost and impact of such industry to rural communities and their way of life.

When, a few years later, the London-based Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM) decided to start a journal, its editors Edward Kamau Brathwaite, Kenneth Ramchand and Andrew Salkey had no hesitation in titling it Savacou. A line drawing of Moody’s sculpture was used as the colophon for CAM publications, essentially becoming the emblem of that movement and, by extension, that of the generation of Caribbean artists who followed in Moody’s footsteps by making Britain their home.

The papers of Ronald Moody were presented to Tate Archive by Cynthia Moody, the sculptor’s niece, in 1995. To further explore some of the archival material cited in this piece visit tate.org.uk/archive.

Orchid Bird was presented by the Ronald Moody Trust in 2019 and is included in Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life, The Hepworth Wakefield, 22 June – 3 November. The Onlooker is on display at Tate Britain and Hope is on display at Tate St Ives.

Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski is an artist and archivist currently pursuing a collaborative PhD on the life and work of Ronald Moody at Chelsea College of Arts (UAL) and Tate Britain. Her book Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life is published by Thames & Hudson in association with The Hepworth Wakefield.