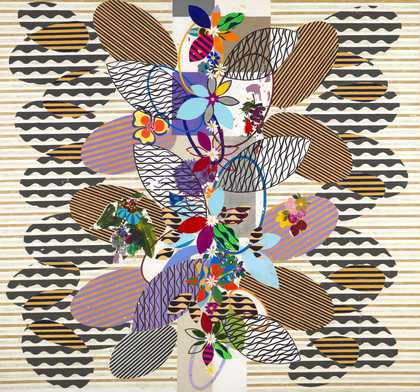

Beatriz Milhazes

Maresias 2002-3

© Beatriz Milhazes Studio. TBA21 Thessen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary Collection. Photo: Fausto Fleury

YARA RODRIGUES FOWLER My mum is Brazilian and I grew up in England, so I feel attracted to your work, from the heart. I am also in Cornwall right now, which is where your exhibition will open at the end of May. If I were to head straight out to sea from my position, on the other side of Cornwall to Tate St Ives, the first land I would hit is Brazil. Like my mum, you grew up in Brazil during the military dictatorship. How did the dictatorship, and then the return to democracy, influence you and your work?

BEATRIZ MILHAZES It was a very difficult time and a tough period for culture in general. I was lucky because my mother was an art historian at the University of Rio de Janeiro and my father was a lawyer, so both of them were very connected to cultural and intellectual fields. They tried to make our lives normal; we went to exhibitions, movies and musical performances.

After school, I graduated in journalism. I didn’t plan to be an artist, but when university left me disappointed, my mother suggested I go to art school instead. So, in the summer of 1980, I started at EAV Parque Lage (Parque Lage School of Visual Arts). I was very young – 20 years old – but immediately had the feeling that this was what I wanted to do with my life.

The school at that time was a network of resistance to the terrible atmosphere in the country. We developed a family, a community, during the three years that I was studying there, from 1980 to 1983. A similar thing happened nationwide, with a generation of young artists contributing to an exhibition that took place in 1984, called Como Vai Você, Geração Oitenta? (‘How are you, eighties generation?’). It was a kind of occupation of the space of the art school. This moment became an explosion. It was the end of the dictatorship and we all wanted to have freedom: freedom of expression and to develop art in new directions, having been used to painting as the main medium. It felt like a very strong political and cultural statement. The exhibition featured 123 artists from all over the country and included paintings, drawings, sculptures, multi-media work, videos, prints, site-specific projects and performances. Thousands and thousands of people came to the show. It was a big party, a celebration of the freedom to speak, be creative, develop, and have our lives back.

YRF It must have been incredible.

BM It was. During the dictatorship, artists were almost obliged to develop their own practice and artistic language based on political issues. In the cultural field, you had prisons; you were not so free to think. My generation got back the possibility of freedom. I wanted to bring back our history and culture, and say: I’m proud to be Brazilian. That is something that includes popular art and forms of expression, like Carnival. In Rio, it’s like a religion. There is exuberance, movement, and freedom for artists to develop themes in whatever way they like. There is beauty. It was my ambition to bring something new – my art history – to international abstraction.

Beatriz Milhazes

Fleur de la passion: Maracujá 1995-6

© Beatriz Milhazes Studio. Thibault Poutrel Collection. Photo: Thomas DuBrock

YRF And do you feel you achieved that ambition?

BM I think I did, yes. I began my international career in the nineties. The history of painting is traditionally a male field in which it has not been easy for women to be taken seriously – as being capable of constructing a solid journey of investigation, or confronting artistic problems with a deep plastic intelligence. I explore my roots on the logical level of forms, bringing together a range of stylistic elements and introducing them into my paintings. In this way, my work reveals a different approach to the medium and discussions around it.

I’m from Latin America and I have a strong interest in pursuing something new and fresh. Painting is considered high art, so my use of popular manifestations of culture, like Carnival, as a reference in my work is certainly uncomfortable. At the same time, I received good support from critics, both in Brazil and internationally.

YRF Your work was recently included in the Venice Biennale as well.

BM Yes, this year I’m participating for the second time. I represented the country in the Brazilian Pavilion in 2003 and, for 2024, I have developed a special project for the Applied Arts Pavilion, a collaboration between the Biennale and the Victoria and Albert Museum. This year also marks a historical moment: it’s the first time that a Brazilian, Adriano Pedrosa, is the Biennale’s general curator.

YRF Growing up, the colour in the house came from my mum, from Brazil. The UK is so grey that whenever we went to Brazil, the sunlight would suddenly feel so bright, the trees so green and the flowers so colourful. When your paintings come to other countries, like the UK, do you feel they become brighter? Do you feel the colours differently?

BM I did my first solo show in Berlin in 2003, with Galerie Max Hetzler. It took place in January. There was snow up to my knees and it was dark by 3pm. It was a really heavy winter and I experienced exactly that feeling: compared to the white and grey snow outside, the bright colours of my paintings were exploding joyously in the room. But at the same time, I think those colours can be quite intense, and sometimes that intensity can be claustrophobic. So grey can create a peaceful atmosphere.

Beatriz Milhazes

O Leme 2002

© Beatriz Milhazes Studio. Monsoon Art Collection. Photo: Sid Hoeltzell

YRF I’ve never thought of it like that.

BM Even the greyest day doesn’t have to be a depressing thing. It’s more about peace, which you can appreciate when you live in the tropics, where the sun is always very intense and everything is extreme, in terms of light, colour and contrasts. My studio is close to the botanical gardens and I think you can see that in nature: a very bright blue sky, very strong greens, vibrant flowers. The popular manifestation of that comes through in the colourful fabrics, the flamboyant costumes.

But while colours are very important in my world, I am also essentially a studio artist. No matter what direction I want to take, when I have a white canvas in front of me, I must focus only on the questions presented by the painting. I know a piece is finished only when I feel the combination of colours, the structure, is complete. Sometimes, a small detail will change the whole situation. Iwona Blazwick, the former director of the Whitechapel Gallery, once said: ‘Geometry organises my imagination.’ I think the relationship between that mathematical system and the complexity of nature is where my work comes from.

YRF I’m curious about the relationship between joy and life and colour in your work, too.

BM It gives me great pleasure to create a space in which I can develop my thoughts, explore complex ideas and conceptual systems. I enjoy being surrounded by a circuit of affections. Geometry gives structure to my sensibility: it turns into diagonals, patterns, textures, motifs and forms. With access to a diversity of tools, I pursue chromatic joy with a poetic bow. The curator Tanya Barson once observed that I approach pictorial space as an environment where an ‘optical move’ takes place. I think it is important to truly experience with one’s eyes. My work reflects a carioca visual intelligence, combining colour in ways akin to an ecological or chemical reaction.

YRF I was lucky enough to see one of your paintings, The Beach, in person two weeks ago, at the Met in New York.

BM That’s from my first show in New York, in 1997, when my colours were more melancholic and I was more interested in the baroque. I was looking to the colonial past and thinking about the mixing of cultures. The work was more figurative then – you can see ruffles based on women’s costumes and lace. As the exhibition at Tate St Ives will show, by the end of the nineties, it was clear to me that I needed to make a choice between abstraction and figuration.

I always saw myself as an abstract painter, but I used elements of figuration, symbols and signs. In the end, I chose abstraction, though I still – even in my most recent work shown in Venice – pick up aspects of the figurative and introduce it into a very abstract surface. I’ve never left it totally behind. I think that being an artist from the tropics, and the exuberant context I grew up, live and work with, makes me think differently.

Beatriz Milhazes

O sol de Londres 2003

© Beatriz Milhazes Studio. Private collection, London. Photo: Sid Hoeltzell

YRF Have you been affected by environmentalism and growing concerns about the climate crisis, particularly as a Brazilian?

BM Yes. Nature plays many different roles in my life, and in my whole process as an artist. The starting point is always the city, Rio. When I began my international career, first in South America and then in the United States, my galleries wanted me to move, to emigrate, but I didn’t want to. That was a very important decision for me. I was still very young, and I thought: Why? My home is Brazil. Whenever I arrived back from my trips, it was super important to find my studio close to nature, as it is this atmosphere that really inspires me to develop my work.

In 2021, I started supporting Client Earth, a British institution that acts around the globe, using the power of law to protect the environment. In Brazil, for instance, they are working with lawyers who are fighting against the invasion of Indigenous land in the Amazon rainforest. I feel good that I’m part of it.

YRF What is the significance of the sea and the coast in your work? And of having your work shown at coastal locations like St Ives?

BM I really enjoy the ocean. The waves, the air, the salty sea breeze, the different rhythms. Taking a walk along the beach is very important for me; it brings me good energy that I take back into the studio. I also like the fact that – for example, you and I, in Cornwall and Rio de Janeiro – we are by the same ocean, but in very different cultures. It’s the same water, but it brings us completely different kinds of possibilities.

The retrospective at Tate St Ives is not huge, but it is thoughtful and sensitive. It contains a whole range of my work made between 1989 and 2023. The year 1989 was a very important moment for me as this was when I discovered my monotransfer technique, which I have been developing ever since. This involves painting with acrylic onto a plastic sheet in the shape of a particular motif, which is then transferred to the canvas when the paint is dry. The process combines concepts of painting and collage, and can result in a pure, painterly, even handmade finish, while ultimately being very controlled and rational.

For artists, every time you do a retrospective, it’s like a review of your life. It makes you re-encounter your old friends; I haven’t seen some of these works for decades. It also suggests possibilities for the future. It’s always a very special and emotional moment.

Beatriz Milhazes

O desfile de leques I 2023

© Beatriz Milhazes Studio. Galerie Max Hetzler. Photo: def image

YRF It’s always very special to see a retrospective of an artist’s work, and I like the idea of the works being connected to you in Brazil via the sea. Cornwall is definitely the most tropical part of the UK, so they are in the right place.

BM I have wanted to visit the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden in St Ives for many years – she is one of my favourite artists. I’ve also never been to that part of England. I’m looking forward to seeing the beautiful landscape.

Beatriz Milhazes: Maresias at Tate St Ives, until 29 September.

Beatriz Milhazes is an artist who lives and works in Rio de Janeiro. Yara Rodrigues Fowler is a novelist who lives in North Tyneside.

Supported by Jonathan & Wendy Grad Charitable Trust and Abigail and Joseph Baratta, with additional support from The Beatriz Milhazes Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation and Tate Members. Organised by and originated at Turner Contemporary, Margate. Curated by Melissa Blanchflower, Senior Curator, Turner Contemporary and Emma Lewis, Curator, Turner Contemporary. The presentation at Tate St Ives is curated by Anne Barlow, Director, with Giles Jackson, Assistant Curator.