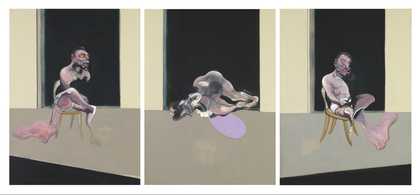

Francis Bacon

Triptych August 1972 (1972)

Tate

Dark as love, darker than death, the black in each of the three paintings that constitute Francis Bacon’s Triptych August 1972 is as soft and as dense as velvet, and its lightless depth is less suggestive of a doorway than it is of an unending void – a drop to hell, perhaps. For most of his personal life and his professional career, Bacon specialised in staring into the abyss, making the act of doing so his vocation, his sexual fetish, his primary hobby, and his most ardent expression of sincere, romantic love. If the abyss returned his gaze, as Nietzsche warned it might, he interpreted its interest as a come-on, recognising in the savagery of the world a kind of furious sensuality, a pulse that kept the time for fucking, painting, drinking, and all the other arts he practiced daily.

‘If I go into a butcher’s shop,’ he once observed, ‘I always think it’s surprising that I wasn’t there instead of the animal.’ He did not admit this to suggest that he felt helpless in the knowledge that he was mere flesh and blood, but to say that he accepted it, and furthermore that it delighted him a little. An atheist who achieved a reputation as the heir to some of history’s best religious painters, he imagined his own God in sex and life force, both masochism and sadism appealing to him as the two ends of an ouroborotic circle of divinity and dirtiness, power and vulnerability, and pleasure and pain.

Triptych August 1972 is one of what are traditionally referred to as Bacon’s Black Triptychs, painted in the wake of his former lover George Dyer’s death from suicide in 1971. In the middle panel, two men, presumably Dyer and Bacon, are locked in something halfway between a brawl and an embrace. The lines around both bodies blur; there is no space between the figures’ flesh, and both of them look as if they might be pulled over the threshold of the void at any moment. Neither of them has a penis, and some scholars have suggested that this absence might imply that what we’re seeing is a fight, and not a fuck. What seems more likely is that Bacon is depicting something beyond sexual congress: love kissing death, death penetrating love.

‘The frustration,’ he once said, with uncharacteristic romance, ‘is that people can never be close enough to each other. If you are in love, you cannot break down the barriers of the skin.’ Here, skin and penetration and physical barriers are obsolete, grief taking over as the ultimate in- carnation of intimacy – one man carrying another in his heart in perpetuity, giving rise to a far greater commingling of pain and pleasure than even the most inventive masochist or sadist could devise.

Triptych August 1972 was purchased in 1980.

Philippa Snow is a critic and essayist based in Norwich. Her first book Which As You Know Means Violence is published by Repeater Books.

To read more of our special feature celebrating Tate Britain's rehang, visit www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-58-summer-2023/alex-farquharson-tate-britain-the-state-were-in