Joseph Mallord William Turner

Norham Castle, Sunrise (c.1845)

Tate

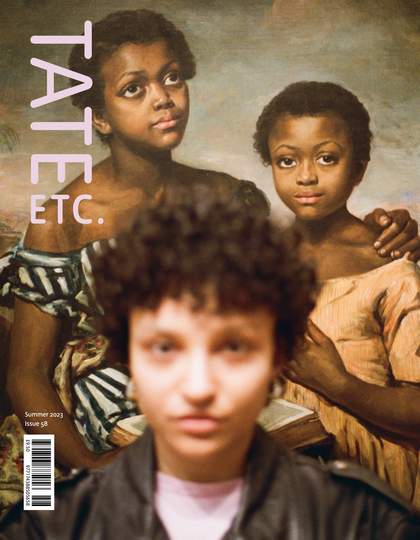

This summer, we are unveiling the first entire rehang of our collection displays at Tate Britain for a decade. This milestone project is a very exciting moment for Tate Britain, offering us the opportunity to rethink how, through the world’s leading collection, we present the story of British art – from the Tudors all the way to the present. It is a project that has been an immense undertaking and several years in the making, involving every curator at Tate Britain, as well as contributions from a great many colleagues across Tate. It best manifests our three guiding principles at the gallery: relating, in turn, art to society, Britain to the world, and the past to the present – principles that we have threaded through our exhibitions programme for some years.

Foundational to the new displays has been the work by curators over the past decade or so to extend, deepen and diversify Tate’s collection of British art. Of the 800 or so works on view, 70 have entered the collection in the past five years alone. These acquisitions reflect the routes taken by art in our time; they also extend and diversify the canon of historic and modern British art as represented at Tate. Thanks to recent acquisitions, we are now able to do much better justice to the significant contributions that women artists, in their ever-increasing numbers, have made to the development of British art from the late 17th century onwards, and to how artists of the African, Asian and Caribbean diasporas have contributed to, and challenged, the accepted narrative of British art in major ways since 1945.

The new rehang of the collection at Tate Britain, invites you, as before, on a journey through art through time. Chronology is retained, broadly speaking. The difference now is that each room is thematic in distinctive ways and curated according to art history’s societal contexts: cultural, economic, ideological, intellectual, technical and more. It is an approach that assumes the art of a given period is inseparable from, and resonates with, the culture and society from which it has emerged. Those contexts offer ways of understanding the art, while, conversely, the artworks offer perspectives on the social and cultural dynamics of their time.

For example, in one room the Georgian period is represented in terms of London and its new urban culture at the time of Hogarth; in the next, the focus is on how the first public exhibitions of British art in the 1760s gave rise to an audience, a market and art criticism for the first time; the following room looks at how pictures contributed to the development of a culture of gentility, which often masked the realities of the sources of wealth underpinning it. Jumping forward, our post-war rooms begin with a view of how art reflected the anxieties and freedoms of the early Cold War era, then shift to show how other types of art were related to the embrace of modernist design and architecture in the reconstruction of urban centres and the building of the welfare state; a later section reveals, how, by the 1960s, in London especially, British life had been transformed by new forms of popular culture, reflecting a period of sustained economic growth and increased social mobility.

While each room appears very specific, both in terms of the art it encompasses and the social and cultural themes highlighted, certain phenomena recur, like cresting waves, at various points across the centuries. These include the growth of cities, the expansion of empire, the rise of industry, the changing conditions of rural life and the natural environment, the struggle for democracy, and art’s variable relationship with popular culture; or looked at another way, class dynamics, women’s histories, diasporic experience, and LGBTQ+ lives.

And wherever significant, the internationalism of British art and British history is emphasised. The rehang reveals a story of British art that is both national and global. For every major British artist who spent their whole life in Britain, there is another major British artist who was born elsewhere, whose identity is cross-cultural, or whose career had a complex international itinerary. That is as true of the very first gallery – devoted to the art of the Tudor and early Stuart periods – as it is of the final contemporary galleries that reflect the internationalism and diversity of Britain’s art scene today.

We have also, for the first time, introduced and commissioned a series of responses, or stealthy interruptions, by contemporary artists. Those works deepen the narratives of specific rooms and enter into dialogues with the historic works they find themselves among, sometimes turning the tables on the world view the latter represents. In momentarily breaking the immersive historic spell, these contemporary works of art also act as reminders that the histories represented in each gallery are foundational for who and what we are today.

For this issue of Tate Etc., we have invited a wide range of writers, artists and thinkers to explore the collection displays with a similar aim in mind. Together, the pieces that follow become our own fellow time-travellers on a new journey through art in Britain.

The Tate Britain New Collection Displays 2023 have been made possible by the generous support of Midge and Simon Palley and The Deborah Loeb Brice Foundation, and from The Ampersand Foundation, The Manton Foundation, The Linbury Trust, The Rokos Family, DCMS/Wolfson Museums and Galleries Improvement Fund, Sir David and Lady Verey, and Shane Akeroyd. Alex Farquharson is Director of Tate Britain.