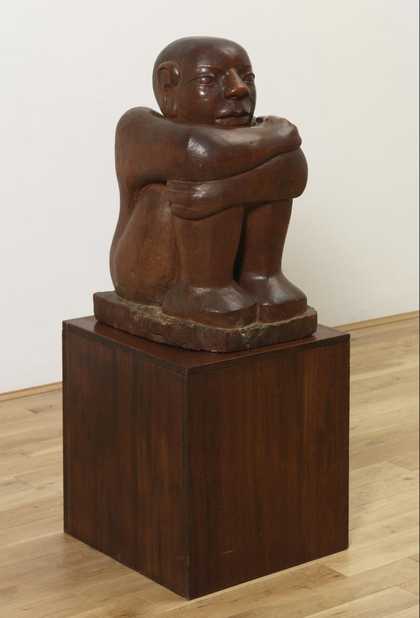

Glyn Philpot

Repose on the Flight into Egypt (1922)

Tate

Glyn Philpot (1884–1937) made his name and fortune as a brilliantly accomplished portrait painter, but throughout his career he produced other works of a much more personal nature, treating subjects from classical myth, the Bible and contemporary life in quirkily original ways. He was raised as a Baptist but converted to Catholicism at the age of 22, and his religious paintings convey the convert’s fervour of discovery, as well as the illicit sexuality that he put, as openly as he could, at the service of his faith. The results are wonderfully idiosyncratic.

In his treatments of two other great New Testament subjects – the Annunciation and the Adoration of the Three Kings – Mary and the holy family are not seen at all. Philpot focuses instead on strange and beautiful male figures – the red-haired angel Gabriel and the very youthful kings. In Repose on the Flight into Egypt, the holy family are present but largely hidden from view. Joseph, who traditionally gathers food or lies flat-out with exhaustion, is reduced to a faceless bundle; of Mary and the Christ child, normally the expressive focus of such a picture, we have only a tiny glimpse. What seizes the attention unforgettably are the boys, fauns and centaurs who gather around the shrouded holy family, and the sphinx who stands guard.

The scene takes place in the mysterious indirect light between dawn and sunrise – the day with all its challenges and potential is at hand, and there is a feeling that once the sun breaks over the far mountains these mythical beings will vanish, like figures in a dream. We are on the threshold of a great change in human history, but for a magical moment the old myths coexist with the imminent new force of Christianity. The two centaurs in the distance and the young man holding a bow seem to keep watch and to warn, while the linked group of centaur, boy and faun on the left are rapt in tender amazement at what they have found, much as the Three Kings had been not long before. At the centre of the picture, the two female figures, black sphinx and white virgin, are depicted as parallel powers – one lit by an arcane flame, the other by an unearthly luminescence. It is the harmonious coexistence of the figures from both worlds that gives the picture its peculiar fascination and suggests the artist’s own doubleness: his investment in both the naked sexuality of the pagan classical world and the mystery of Mary and her child. Theological tensions caused by his homosexuality are explored, if not resolved, in the dream world of mythic art.

Dreamlike, too, is the landscape where this strange tableau is staged – rocky desert merging undecidably into coastline and grey sea. In Renaissance depictions of the subject, the holy family are seen in typical northern or Italianate landscapes but never in settings actually suggestive of a desert journey. Philpot perhaps takes a lead from a much-reproduced painting The Rest on the Flight to Egypt of 1879 by Luc-Olivier Merson, which places the Flight in a symbolic Egyptian landscape, where Mary and her child fall asleep between the colossal forepaws of a statue of the Sphinx. Philpot, who has his sphinx brace herself against a fallen colossus, seems to merge this ‘Egyptian’ geography with visions of the pagan world in Florentine art. Botticelli’s mysterious Pallas and the Centaur c.1482 in the Uffizi in Florence, and the satyrs and centaurs in a number of paintings by Piero di Cosimo, surely inform the Repose (which Philpot painted in Florence), as do the naked men in Luca Signorelli’s frescoes of the Resurrection in Orvieto’s cathedral, which he visited at the same time.

This discourse with great artists of the Renaissance subtly enlarges the dialogue between the classical and Christian worlds that the painting represents. The thorns and red flower of the prominent cactus (a plant not native to Egypt) add one more unignorable symbolic note.

Repose on the Flight into Egypt was purchased in 2004.

Alan Hollinghurst is a writer who lives in London.

To read more of our special feature celebrating Tate Britain's rehang, visit www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-58-summer-2023/alex-farquharson-tate-britain-the-state-were-in