Hew Locke

Armada 2019

Wood, textile, metal, string, plastic, rubber, paper and paint

© Hew Locke. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2021

‘The city was a collage of thrilling dissonance...’

Jeff Young, Ghost Town: A Liverpool Shadowplay (2020)

Liverpool has always been a city on the move. Positioned where the tidal mouth of the River Mersey meets the Irish Sea, it was one of the world’s major trading centres in the 18th and 19th centuries. Movement helped to build the city up: waves and tides, ships coming and going, the busy activity of workers in the docks, the flow of goods to and from distant places, transatlantic journeys.

The city played a pivotal role in the growth of the British Empire, becoming not only a centre for trade, but a hub for the mass transportation of people, including enslaved people, and emigrants from Europe to North America. By 1795 Liverpool controlled nearly 40 per cent of the entire European slave trade. This is a history that still weighs heavily today.

A ship named Discovery docked in Liverpool, photographed by Eileen Agar, 1930s

© Tate. Tate Archive TGA 8927/16/28

Liverpool has also always been a centre of movement in another sense: a ground zero for some of the most exciting and influential social, political and cultural movements in Britain’s recent history; home of The Beatles and Merseybeat; acclaimed in 1965 by Allen Ginsberg as the ‘centre of consciousness of the human universe’.

The new collection display that opens at Tate Liverpool in February 2022 seeks to address all of these ideas, and more – showcasing artworks that connect with the city in its broadest sense, addressing Liverpool’s past and looking to its future. Each part of the display represents a different type of movement, with migrations, social change, and rethinking artistic movements as key themes.

This is a vision of Liverpool that is both global and local, representing international art practices and discourses while never straying from its city context. The artworks included explore migration, exchange, and legacies of the slave trade – topics intimately related to Liverpool and its diverse communities.

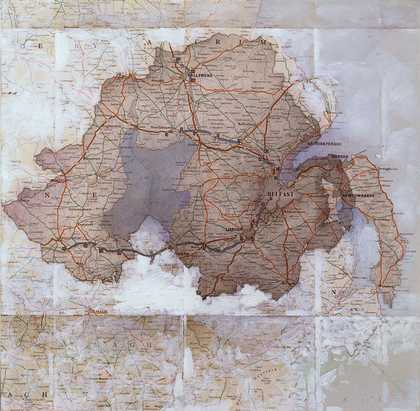

The first part of the display engages directly with Britain’s colonial history. Upon entering the galleries, you’ll see Hew Locke’s Armada 2019 suspended at eye level in the air. This flotilla of vessels – Elizabethan ships, yachts, the Empire Windrush – hang like flotsam but point in the same direction. Armada shows a messy multilayered history, and traces the impact of empire and migration from the 17th century to the present day – how today’s refugee is tomorrow’s citizen. The work of Rita Donagh, meanwhile, deals with the violent conflicts in Northern Ireland during the 1970s and 1980s, a reverberation of the partition of Ireland in 1921 after centuries of colonial rule.

Cumulus 1998, by the Liverpool-born artist Tony Cragg, consists of stacked glass vessels, intricately layered like rock strata, referencing systems of classification, geology and the weathering effects of time, but perhaps also the history of the gallery itself, a former warehouse that would have once been filled with stored and stacked objects to be moved around and traded.

Tate Liverpool in Liverpool’s Albert Dock, a complex of dock buildings and warehouses which was redeveloped into a heritage site in the 1980s

Photo © Rikard Österlund

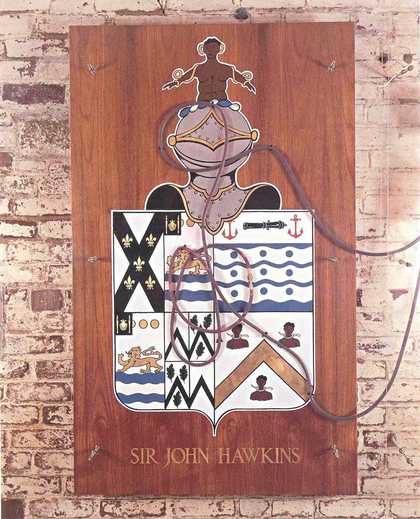

Donald Rodney was a British artist and key member of the Blk Art Group, which questioned Britain’s social, cultural and political legacies by appropriating and reinventing past art. Visceral Canker 1990 presents two plaques bearing heraldic images; one symbolises John Hawkins, the first slave trader to sail from Plymouth, the other Queen Elizabeth I, who granted Hawkins the use of a ship from the royal fleet. The plaques are linked by tubes, through which imitation blood is pumped, symbolising the movement of enslaved peoples in a system that was institutionalised from the outset. Rodney suffered from sickle-cell anaemia and his own health issues generated a personal urgency to articulate the historical pain of colonialism.

The Tree of Forgetting 2013 by the Brazilian artist Paulo Nazareth is a video installation which provides a poetic unravelling of the violence of colonialism. The work refers to a tree in Ouidah, Benin, once one of Africa’s largest slaving ports. Enslaved people were made to encircle the tree several times, a ritual intended to erase their memories of the past. In the video, the artist walks backwards around the tree 427 times, symbolically challenging the historical act of erasure.

The display at Tate Liverpool also challenges received art histories, examining the ideals of collaboration and exchange embodied in movements such as the Bauhaus through a non-Western lens. Kader Attia’s Untitled (Ghardaïa) 2009 is a scaled model of ancient Ghardaïa in Algeria, made from couscous, and appearing alongside three prints: two showing the architects Le Corbusier and Fernand Pouillon, and one of the UNESCO evaluation of the region as a world heritage site. The work looks at the troubled relationship between East and West, colonised and coloniser, and also speaks to the city’s precariousness – the city crumbling over time.

Journeys Through the Tate Collection, Tate Liverpool, from 14 February 2022.

Hew Locke’s Armada was purchased with assistance from Tate International Council and with Art Fund support in 2021.

Helen Legg is Director, Tate Liverpool. Darren Pih is Curator, Tate Liverpool.

Vanley Burke

Vanley Burke

England Expects Every Man to Do His Duty c.1980s

© Vanley Burke. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2021

My first introduction to Liverpool was in the mid- 1980s. It was a pretty grim time for everyone, and perhaps especially for people in Liverpool. I travelled up as I was participating in Connections, an exhibition with photographers Martin Parr and John Davies exploring links between Liverpool and Manchester. I had done a lot of reading beforehand and my research had basically indicated that every brick in Liverpool was built from the blood of a slave. So I went looking for that, walking across the city. I was trying to find traces of the city’s history – in the people around me, in the architecture, in the place names. I found a road called Mount Vernon, which was the name of my school back in St Thomas, Jamaica. And all the time I was thinking, what’s the connection?

It was on one of my walks that I stumbled upon the Nelson Monument, behind the town hall. It’s the oldest monument in the city, celebrating Britain’s victory over France in the Battle of Trafalgar – one that strengthened Britain’s naval dominance and empire building. I remember that I couldn’t understand the chained characters when I saw them. I had always associated these images with Africans, but suddenly here was a man with white European hair, a Spanish or French prisoner of war. It was, for me, an absence of representation. I thought, not even in the misery of our despair can you offer us the dignity of identifying or portraying us. Above them is the figure of death – a sort of skeleton emerging from the drapes of a captured flag – and a woman, Britannia, holding a laurel wreath, but she seems so appalled at the scene before her that she turns her head aside. She is the only one raised above the mire.

For me, the monument drew attention to the human cost of our history. It made me realise the scale of slavery – this was just one city, in a country with many similar cities. It also conjured an idea of Liverpool: a once glorious city, on its knees. It was a statue dedicated to imperial glory amid derelict warehouses and abandoned spaces. This encounter was the start of a long relationship with Liverpool.

Vanley Burke is a photographer who lives and works in Birmingham

John Akomfrah

Donald Rodney

Visceral Canker (detail) 1990

Perspex, wood, silicon tubing, gold leaf, plastic bags and electrical pump

© The estate of Donald Rodney

I’ve been going to Liverpool for a long time – I’m a fanatical Liverpool FC supporter and go back as often as I can. For me, Liverpool has always been a place of surprises.

Soon after we formed the Black Audio Film Collective, we started to seek out similar groups germinating across Britain. Immediately after the Brixton riots in 1981 there seemed to be an emergence of young people of colour across the UK who wanted to make film, and Liverpool was a real centre of creativity so we went up there to see what we could find.

There was an immediate sense that it was an older community. There was a flow of stories about family life that seemed to go back much further than ours did. Our conversations were rehearsals of scenarios that had not yet happened. Liverpool was a place to look for clues for our future. It was both optimistic and cautionary.

Our documentary A Touch of the Tar Brush (1991), filmed in Liverpool, started with J.B. Priestley’s English Journey (1934), an account of the author’s travels across England in 1933, and the social problems he saw. I was shocked when I first read it, because there was so much in it that I hadn’t known. We travelled to Liverpool to try to find the families that Priestley speaks to in English Journey, but we couldn’t. Liverpool epitomises something about the African diaspora: the theme of disappearance. When you go through the stories of Black British lives, they suddenly disappear, and we were trying to rectify that.

The whole city seemed to tell a cautionary tale about race. The standard narrative around racism was that if everyone was completely integrated, all was well. However, the people we spoke to were rooted to the place but also suffering from a system that excluded them from jobs, from certain areas, and from city life. It was a paradox. You had a narrative of racelessness, coexisting with a certain kind of segregation. It was perfectly possible to go to Liverpool and be part of a racial republic. Certain areas felt like utopian spaces. But it also felt like those spaces were in a real battle with the rest of the city. These were areas that were built up on generations of utopian aspirations. That’s why I went there. But you could also see the lines of demarcation. Someone will speak of a utopia, and another will speak of exclusion. But it was both.

Liverpool always felt closed, but not inwardlooking. A closed convivial space. It was territorial, and non-parochial. There were people with competing territorial claims. And provided you were willing to enter it on its own terms, you were welcome.

Part of the turn that we have to make in the art world is to challenge the curatorial mainstays – schools, regions, climates – and turn to other themes: the social and political history of a place, the demographics, the vernacular, questions of identity. If you start to look at the world around you very closely, everything else can follow. Galleries need to be more forensic with the local. Once you become forensic, new worlds open up – new pillars of power, new relations of desire.

John Akomfrah is an artist and filmmaker based in London.

Mark Leckey

Rita Donagh

shadow of six counties (c) 1980

Graphite and acrylic on paper 36 × 36.2 cm

© Rita Donagh

I grew up in Ellesmere Port on the Wirral, which is in the magnetic field of Liverpool. As a youth in the late 1970s and early 1980s there was a lot going on in the city in terms of music and fashion. Although the industry of Liverpool was in ‘managed decline’ there was a huge amount of energy and creativity that remained pretty much invisible to the cultural centre of London. That meant that the culture of Liverpool created a very independent identity. It allowed a working-class culture to develop and thrive.

The city was very politically conscious: the dockers, the car plant workers, the whole city was unionised. Part of the trade union movement was about education – you needed to be conscious of your class and of material conditions. That allowed for a very modern engagement with the world.

Tony Cragg

Cumulus 1998

Glass 265 × 120 × 120cm

© DACS 2021. Photo © Tate

I always imagined that when I was old enough I would go and work at the shipbuilders Cammell Laird, but by the time I left school the shipyard had gone. Instead I went to art school in London and had to adapt. I became inculcated with another language, another mindset that I often found very alienating. In order to succeed as an artist I had to learn a new set of values that were essentially middle-class values. So I think it’s important to ask: How do you bring people with their own culture into art without changing them, and without imposing a set of values on them?

Moving to London essentially abstracted me from who I was when I was younger. If you’ve lost what you grew up with, you can’t help but get stuck in a nostalgia trap, but again, I don’t think that’s a wholly bad thing. Nostalgia is neither reactionary nor necessarily backward-looking – nostalgia can be an energy. Nostalgia can be accessed as a way of pushing things forward, as a means of progression. Nostalgia can mean remembering your roots, and the values that are worth continuing and promoting.

Mark Leckey is an artist who lives and works in London.

Sumuyya Khader

![Lionel Wendt [title not known] c.1933–8 Gelatin silver print on paper](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/Lionel_Wendt_title_not_known.width-420.jpg)

Lionel Wendt

[title not known] c.1933–8

Gelatin silver print on paper 38 × 30.5 cm

Photo © Tate

My art is inspired by the world around me, probably like any artist. But I am an artist who has never been just an artist. I’ve always had to make a living alongside my art and draw inspiration from what’s around me, because I’ve had no time to seek it out. That’s not just an aspect of my practice, but something that’s been instilled in me from when I was very young. I was always told to look up. It’s a key thing, especially as a Black child: ‘Don’t walk with your head down – walk with your head held high. And if you don’t understand what you are seeing, ask questions, because it’s the only way you’ll make sense of the world around you.’

There is a lot to take in, growing up in Liverpool. You are always surrounded by a huge number of references, from football and music, to history and the slave trade. The city can be jarring, but it can also be inspiring – it’s that Scouse thing of someone yelling your name from across the road while you’re having a very introspective moment. It’s faces and language – it’s not just the things you see but also the people you meet, the conversations you have. And all that builds to a beautiful palette that I use as a basis for my art.

I’ve also always understood Liverpool as a migrant city. My mother’s mother had Welsh and Irish ancestry, and my mother’s father was from Somalia. My dad has Nigerian heritage. When I was growing up our household was very conscious of our community, and of the idea of Liverpool as a melting pot. If you look at the estates in the 1960s and 1970s, there was racism, and real societal issues, but also a strong identity and a strong sense of community.

If you look back to the 1980s, and the Toxteth uprisings in 1981, the government’s reaction was managed decline. That was the response that Thatcher thought was appropriate – the expectation being that the city would just fade away. But at the same time, there was a thriving community of artists who were doing their own thing, and saying, ‘If institutions are interested in contributing or supporting us, let them come to us. Let’s hear what they have to say.’ That needs to happen more today. My references go back to the 1980s, but I’m aware that I am part of a broader artistic tradition, and a broader heritage. Again, it comes specifically back to community, and the desire as an artist to be connected to something bigger. Liverpool is an extraordinary city.

Sumuyya Khader is an artist who lives and works in Liverpool.