Mark Leckey performing under the bridge at MoMA PS1, New York in 2017 as part of his exhibition Mark Leckey: Containers and Their Drivers

Photo: Derek Schultz

PAUL FARLEY We both grew up on the edge of Liverpool, in similar kinds of places and at the same time – from the late 1960s through to the 1980s. Back then I wasn’t sure if England existed, or, atleast, I was sceptical. In my home town, it felt as if the place didn’t have any of the texture of age, because it was all recently built. It smelled of paint, putty, freshly sawn timber and concrete. Even at a young age, I remember feeling nostalgic for the city that we’d moved from. This was also the long aftermath of the Industrial Revolution, something William Blake witnessed at its inception. Thinking of Blake and his ‘green and pleasant land’ and ‘dark satanic mills’, what was your sense of England when you were growing up?

MARK LECKEY I have always thought of England as being the home counties, so I never thought of myself as particularly English. I still have a problem with the idea of it and tend to say that I’m British. Around Liverpool, I had always felt a sense of not being English, maybe because of the Irish and Welsh elements associated with it – and also the cliché that Liverpool looks to the sea, rather than inland. It was like living in a border town rather than a part of England.

When we moved to Ellesmere Port we lived very close to Capenhurst Nuclear Services and Shell Stanlow oil refinery. Being surrounded by these industries gave our suburb a different atmosphere; it was a strange place that felt constantly toxic. I also remember being terrified of the idea of a nuclear Armageddon. Somewhere I had seen the Soviet Union’s ‘strikelist’ – the key places it would target in an attack – which featured London, Coventry, Manchester… and Ellesmere Port.

Video still from Mark Leckey’s Dream English Kid, 1964–1999 AD 2015

© Mark Leckey, photo: Mark Blower

PF I think of this period as a time when, for us, the world went from black and white to colour, and this is a sense I get strongly from your work, such as in your film Dream English Kid, 1964–1999 AD 2015, which is a kind of collage of found memories from this period: adverts, props, music, and noises off, like Harold Wilson’s ‘white heat of technology’ speech. All these are threaded through with images of a newmotorway and a bridge (from Eastham Rake on the Wirral), both of which age as the film progresses. The piece you’re making for Tate Britain is going to feature a life-sized model of this bridge, something that you’ve returned to in a few recent projects. Tell me more about why this bridge has been so important to you over the years.

ML It stands for a lot and functions like a rampant metaphor generator, but in essence it’s something that’s been displaced from the Wirral, like a surrogate of me or where I’m from. It comes from a strange encounter that I had when I was a kid. When I did English O-Level, I was asked to write a story about my childhood. I thought, I’ll write about a time when I was about eight or nine. I used to hang around with friends up in the alcove at the top of a slope underneath a motorway bridge, and on one occasion I saw a pixie. As I was writing the story, I suddenly realised I had broken the spell of what I had believed in my childhood: I had had this supernatural encounter and had continued to believe in it entirely until I was a teenager. This story has lingered with me for years. Later I started reading a lot of old Irish folklore, which included stories of encounters similar to mine, neither benign or malevolent. In Ireland they’re called the good people – you say that to respect them because you’re afraid of them, just in case they’re listening. It was straight out of a Yeats poem. So the bridge is a project about these pixies, fairies and scallies.

Record sleeve mock-up for Mark Leckey’s Under Under In 2019, using Henry Fuseli’s painting Cobweb 1785–6

© Mark Leckey

PF As well as the bridge featuring in various ways in your work, you’ve recently produced a record: Exorcism of the Bridge@Eastham Rake 2018.

ML It was a failed exorcism, because I was trying to rid myself of this bridge, but I also wanted it to feel like a space where you could perform some kind of ritual or ceremony.

PF Yes, it’s poetic, and it’s also an invocation. In an attempt to help cast out super-ghouls and demons, you call on the mythical and actual – Gog and Magog, Barbara Castle, the Wyrd Systers of Albion, the Transport and General Workers’ Union, to name just a few! It’s also a litany of obstacles to a New Jerusalem, which leads us back to William Blake. What attracts you to him?

ML What I see in Blake is a glorious sense of rebellion, a true radicalism. That is what I’m trying to invoke as well. You and I are of the same age and these are all the things that were invoked in records, alternative histories, where you learnt about all these figures that were rebellious, those who were trying to change the system. Now, I don’t know. There are so many histories, the idea of an alternative history seems fraught.

PF Is it a privileging of the imagination over the rational or material?

ML What I look to Blake for, I think, is his frustration or disappointment, or, even better, his war against reason, against reductionism. In contemporary art there’s a push towards abstraction – not as in ‘abstract painting’, but that reductionism where everything gets distilled to formalism, I guess, in the end. I want that same kind of bodily exuberance that Blake brought. There’s also sensation, there’s touch – all these things are included in art, but sometimes they can be abstracted away, academically, intellectually, whatever. But people are always trying to return to it. I think someone like Blake is a good figurehead in that sense. You just keep returning to the body, to your appetites, to your desires, to what makes you alive in the world.

Video stills from Mark Leckey’s Under Under In 2019

© Mark Leckey

PF If we think of Blake as a total artist, operating on several fronts and in several spheres – he isn’t just a painter, he isn’t just a printmaker, he isn’t just a poet – would you say you’re doing something similar?

ML No. I only say ‘No’ like that because of his productivity. The work he generated was phenomenal. He was touched, wasn’t he? There’s something driving me, but not to the degree that I think it drove him.

PF He was an industry, a force of nature. But you do seem hungry to take stuff from all over the place and see what you can make with it. At one point in Dream English Kid, among all the found footage and sound, is a machine you’ve built from the detritus of the age – ciggie boxes, Tate & Lyle tins, spools and diodes and hoover bags...

ML Yes, maybe that’s a similar thing. It comes out of a suspicion of academia and so you’re always looking outside for other means for production. My favourite of Blake’s words were those about being lost in the paradise of the work; that state in the working process where you’ve just begun to build something, when you can step inside it and start inhabiting it, and the joy that comes with that. I’ve always had the idea that it’s as if you’re reaching for the point where the work, or you, are a perpetual motion machine, and it’s almost unthinking – there’s enough material being fed in that it can just burn.

PF Blake can also be seen as an awkward customer, as an artist – the rebel, as well as the radical poet and dissenter – speaking truth to power. Is that awkwardness necessary?

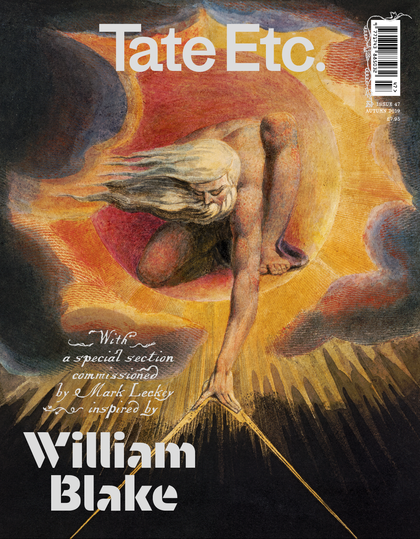

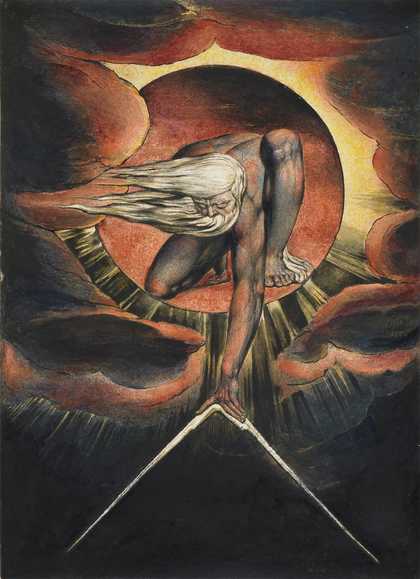

ML I saw a show in Liverpool recently at The Bluecoat called Instituting Care [an exhibition by artist Jade Montserrat] and the title really struck me. I thought, That’s where art is now – an idea of art as a platform for attending to people’s wellbeing, mental health, whatever it is, which is very at odds with the idea of the artist as rebel, as antagonist. But then, in order to institute this care, there has to be conflict – conflict with the institutions that want art to remain, to retain that older idea of a rebel. What you’re getting now is a lot of young artists who I wouldn’t say are seeking conflict, but they do embrace it; they’re looking for change. They’re looking for change in order to ‘institute care’, rather than just to be that kind of sovereign being, one that I think Blake wanted to be and, in a way, one that I was inculcated in becoming: the artist as self-willed aristocrat, free from social norms and niceties. I think that’s being buried as we speak; it’s been a long process. It’s so gendered, all of this – this idea of the very male, selfish, awkward bastard. But there’s something about Blake... to me, he’s beautifully androgynous – just think of his figure of Albion (from his A Large Book of Designs c.1794–6). I still believe in the idea of not fitting in, but I don’t believe in the idea of not fitting in as validating some heroic figure.

William Blake, Albion Rose c.1793, colour engraving and etching with hand-colouring on paper, 36.8 × 26.3 cm

Courtesy The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

PF Blake certainly thought anybody with a pair of eyes or ears could hear it, see it, could get the work, just on that basic level – that there needn’t be any screens or barriers to perception. Do you recognisethat?

ML Yes. The only criticism that ever really cripples me is if someone says it’s fancy-pants art and that it’s inaccessible in some way. I’m trying to counter that response. When I was at art school I felt intellectually out of my depth and alienated by the critical theory that was being taught – I had had no experience of reading at that level. So I left art school, thinking I couldn’t be an artist, that I didn’t have the intellectual capacity to make art. The way I found my way back to it was thinking that, actually, what I wanted to make was something within my own experience, something that was essentially local to me and that I could speak of with authority. That’s when I began making work about my past, when I got caught up in my own pathologies. I started mining those for material. Recently, I’ve started thinking that maybe I constantly return to the past because it’s a class issue, and I’m looking for a language that’s been superseded by art, in a way. I’m trying to find the language that I grew up with.

PF You’ve said you’re not really so bothered about people thinking about your work – as in seeing it and having a thought. Are you after something more visceral, is that the right word?

ML Yes, psychedelic maybe. I find a lot of art gets reduced to some think piece, or it becomes discursive in that sense, and that becomes its value. I find that (1) dull, and (2) after having taught at art school, I came to see how easy it is to produce that effect, to create thought. It’s already there, so it just needs the trapping of art to trigger further thinking.

PF You’re just mobilising something.

ML Yes, exactly, mobilising – that’s a nice way of putting it. Usually the work I make is about how something has affected me, has literally altered the state of my mind or impacted on me to such a degree that it’s wrenched me in some way. I’m trying to feed that back and produce that effect in what I make. I’m almost saying: Look, here’s what this did to me – does it do it to you? That’s basically the question I’m asking. I’m saying: Don’t think; try not to think of this. The most depressing aspect of making art is that people find thinking about art is difficult, so, even when it’s not, there’s still this barrier to access. They still think it can’t be that simple. You make a video of people dancing and they’re like: So what’s it about? You’re like: It’s about people dancing. But it’s art; it can’t just be about people dancing.

Installation views of Mark Leckey’s Dream English Kid, 1964–1999 AD 2015 at Cabinet, London, 2015

© Mark Leckey, photos: Mark Blower, courtesy Cabinet Gallery

PF We’ve mentioned your film Dream English Kid, which I love and find to be a very tender excavation of a past; there’s an implicit connection to Blake again, the idea of a fallor the fall, of passing into knowledge and experience – from innocence to experience.

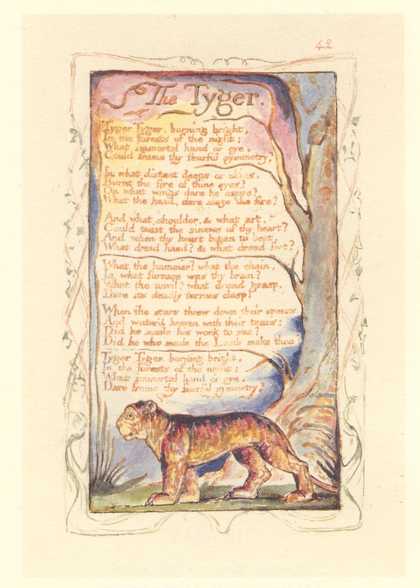

ML What it made me think of is the mind being introduced into technology, and what that does to the mind, and how it gets caught up in a feedback loop. That’s what Dream English Kid is about – trying to create some idea of an autobiography, but knowing that I’m just a by-product of petroleum, the effluent that’s coming off this technology. I’m thinking a lot about Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience at the moment, because this piece I’m making for Tate Britain now is about childhood. That rite of passage, moving from this state of innocence to experience, and then thinking about the politics of that: who gets to be innocent and who gets to be experienced, as a child. Some people remain forever in innocence because of their environment, or because their privilege allows that to continue. So I’ve been gleaning from Innocence and Experience a lot. It’s enchanting, and when you get to his poem ‘The Tyger’, the spell is in full effect and you don’t even know you’ve been bewitched. That’s where I’m always fascinated by poetry, that point where something catches you and you return to it, thinking that you’ll understand what’s caught you, and yet you never do. I have that with ‘The Tyger’. I still don’t know what it is, and I couldn’t distil it in any way.

William Blake, ‘The Tyger’, from Songs of Innocence and of Experience Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul 1794, 54 relief etchings, hand-coloured with watercolour, with some gold, bound in calfskin, 11 × 7 cm (page size)

Photo © Tate

PF You once said that you ‘wallow in the mire of nostalgia’. Is that a good or helpful thing for you?

ML I think people of our generation have reached an age where we’ve inherently turned to nostalgia, as part of the aging process. But, at the same time, it’s been massively amplified by technology. You’re in this constant echo chamber of nostalgia. I always have the feeling that it’s like a habit you’re trying to break. All right, watch one more Joy Division video on YouTube. I mean, that’s where Dream English Kid came from. I went to see Joy Division at Eric’s in Liverpool in 1979 and have dined out on it ever since. Then, one day I was on YouTube and I found the audio of that very gig. I found that very estranging, disorientating.

PF You weren’t there, but you were intrinsically there? The found memory?

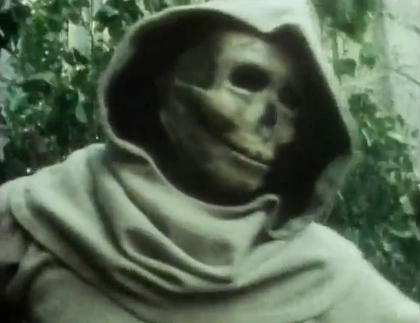

ML It was like discovering some footage of me hanging around the chippy when I was 15. I thought, well, maybe I could access all of my life. It sounds like a weird kind of narcissism maybe, but that’s what I thought when I heard it. Another example: I remember at a certain age becoming frightened to go to bed after a TV episode of Black Beauty, and all my adult life, if anyone ever argued about a horror film, I’d say I was terrorised by Black Beauty – the most innocuous, innocent crap. But then I got to see the clip that terrorised me again, and it is truly frightening! We all have these instances in our lives in this archive that we can draw on. How could you not be nostalgic, how could you not want to feast on all of that? It’s too delightful, it’s too delicious.

Still from The Adventures of Black Beauty, season 2, episode 8, ‘Out of the Night’, original transmission 11 November 1973

© LWT Productions Limited

PF It’s a complicated word, nostalgia – pain and home.

ML Our generation also grew up with a sense of a once-proud working class, something that was lost in the course of a generation. You’re surrounded in Liverpool, on the Wirral, by collapsed industry. Then there’s some kind of Irish sense of the old country, so I think it’s to do with where we’re from as well. Turning back to England, it’s a nostalgia for Empire and all sorts of things we haven’t resolved, but which are all coming to some psychic head now. It’s like an untutored sense of history. There are very different nostalgias: The pleasure of when you were a kid evoked in some pop song from the early 80s; then there’s the nostalgia that I get sometimes on Instagram on coming across a photo of some aspect of youth culture you thought you remembered, but no-one had ever captured, and suddenly there’s this photograph. And you think, that was it, that was it, that, that, that. There is another kind of nostalgia too, which makes you feel ill – it’s just too much and it’s awful and you don’t want to look at it; you’re compelled and repulsed at the same time.They’re hitting different parts of your consciousness.

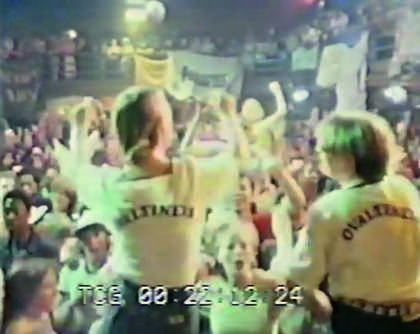

Video stills from Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore 1999

© Mark Leckey

PF There’s a line in a Michael Donaghy poem: ‘The past falls open anywhere…’ Which suggests you can fall into it.

ML The film I made in 1999, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, is constructed out of nostalgia. It was like an exorcism. I wanted to rid myself of it – I was burdened with it. It’s 20 years since I made it and I played it the other day and started talking about it – and got nostalgic for when I made it. That’s a loop, isn’t it? I was remembering sitting there editing, and this intensity returned to me and I realised I had become nostalgic for the time I was making something about nostalgia…

Mark Leckey: O’ Magic Power of Bleakness, Tate Britain, 24 September 2019 –5 January 2020, curated by Clarrie Wallis, Senior Curator, Contemporary British Art and Elsa Coustou, Curator, Contemporary British Art, with Aïcha Mehrez, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain. Supported by Tate Patrons.

Mark Leckey lives and works in London.

Paul Farley is a poet. His new book Selfie with Sea Creature is published in October by Picador.