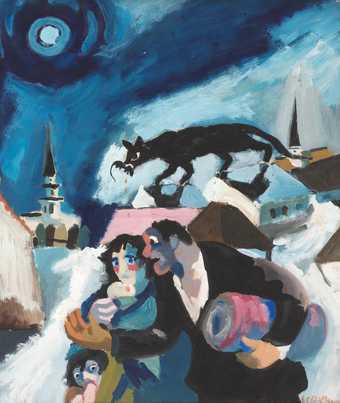

Josef Herman, Refugees c.1941, gouache on paper, 47 x 39.5 cm

© Estate of Josef Herman. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2018, courtesy Ben Uri Gallery & Museum / Bridgeman Images

Piet Mondrian, Naum Gabo, László Moholy-Nagy, John Heartfield, Kurt Schwitters, Oskar Kokoschka – all these artists are now firmly part of the canon of 20th-century art history. But some might forget that all of them spent time in Britain in the late 1930s and early 1940s, as part of that remarkable group of refugees from Nazi-dominated Europe that so complicated and enriched the British cultural landscape. Most of these artists may shortly have moved on to the USA (where some, like Anni Albers, had already found refuge), or in due course returned to East Germany, but a great many others remained and made Britain their adoptive home.

In fact, over 300 visual artists left their native countries as a result of National Socialist racial and cultural policies, and arrived in Britain, thanks in no small measure to the practical support offered by organisations such as the Artists’ Refugee Committee, set up not by the British government, but by well-meaning, committed individuals such as Roland Penrose and Margaret Gardiner. By no means all the émigrés were exponents of a radical modernism or as well-known in their countries of origin as the above-mentioned artists, and, indeed, many of them admitted that exposure to English ways impacted on their practice. Sculptor Siegfried Charoux, for example, described how ‘in England under the influence of political freedom’ his style changed ‘completely from his distorted Austrian to a more free and tranquil one’.

For artists like Mondrian, Gabo and Moholy-Nagy, the way had been paved by a small but significant number of British artists (spearheaded by Ben Nicholson) who were keen to ally themselves to European geometric abstraction. The dadaist impulse represented by Schwitters, however, fell on barren ground during his lifetime and was embraced only in the late 1950s by British pop artists such as Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton. And despite the pre-existence of a British tradition of political caricature, there was little appetite or commercial demand for Heartfield’s bitingly witty anti-fascist photomontages.

Oskar Kokoschka, Self-Portrait of a Degenerate Artist 1937, oil paint on canvas, 110 x 85 cm

© Fondation Oskar Kokoschka/DACS 2018, courtesy National Galleries of Scotland, on loan from a private collection

Most of the émigré artists, however, leant towards an expressionist style, and their painterly, unashamedly subjective tendencies (as seen in Kokoschka’s defiant Self-Portrait of a Degenerate Artist 1937 or Marie-Louise von Motesiczky’s Old Woman, Amersham 1942, now in the Tate collection) were not always well received either by the public or by many in the British art world. This was an attitude reflected in Raymond Mortimer’s disconcerting review of the 1938 Twentieth Century German Art show, published in the New Statesman and Nation. Mounted in London as a riposte to the notorious Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich the previous year, Mortimer said of it: ‘In so far as the German exhibition at the New Burlington Gallery is propaganda, it is, in my opinion, extremely bad propaganda. People who go to see the exhibition are only too likely to say: “If Hitler doesn’t like these pictures, it’s the best thing I’ve heard about Hitler.” For the general impression made by the show upon the ordinary public must be one of extraordinary ugliness.’

Hans Feibusch

1939 (1939)

Tate

Josef Herman

Evening, Ystradgynlais (1948)

Tate

Other works in the Tate collection that were created in the 1930s and 1940s by émigré artists such as Josef Herman, Jankel Adler and Hans Feibusch certainly wear their hearts on their sleeves. Exceptions include Austrian-born, Cornwall-based Albert Reuss, whose work never made direct reference to his life experiences, but whose portraits, interiors and landscapes retained a deep melancholy and sense of isolation, if not alienation, long after the war had ended. As the Second World War receded, however, their subject matter shifted, for the most part, from images making explicit reference to loss and dislocation to more neutral ones, in which emotion resides more in the handling of paint and colour than in the iconography. A case in point here is Josef Herman, creator in the early 1940s of anguished works such as Refugees c.1941, but who remains best known for his slightly later images of the South Wales mining community of Ystradgynlais, in which he found a surrogate home for the Polish-Jewish one he had lost for ever.

The émigrés’ post-war activities as teachers in many of the leading British art schools (Martin Bloch, Harry Weinberger and Georg Mayer-Marton are notable figures here) had a considerable knock-on effect, leading to a more widespread acceptance of the primacy of colour and the importance of emotion. Leipzig-born graphic artist Hellmuth Weissenborn’s exhortation to his students at Beckenham School of Art (later Ravensbourne College of Art and Design) in Kent – ‘Be quite quite BOLD’ – neatly combined Germanic assertiveness with English understatement.

Eva Frankfurther, Couple with Infant 1956, oil paint on paper, 75 x 56 cm

Private collection, © Estate of Eva Frankfurther, courtesy Ben Uri Gallery & Museum, photo: Miki Slingsby

Artists who arrived in Britain as child refugees in the late 1930s (most famously Frank Auerbach and Lucian Freud, but also Harry Weinberger and Eva Frankfurther), although trained entirely in the UK, seem also to have perpetuated an expressionist tradition in this country – one that emerged triumphant after several decades, during which the very medium of painting had fallen into seemingly terminal neglect. Indeed, the recent All Too Human exhibition at Tate Britain posited intriguing links between Russian-born, Paris-based Chaïm Soutine, David Bomberg (the British-born son of Polish immigrants), Auerbach and Freud – all of them of Jewish origin.

As the founding director of New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts is supposed to have put it in the 1930s, crudely but not inaccurately: ‘Hitler … shakes the tree and I pick up the apples.’ This mention of the perpetrator of the Final Solution is a salutary reminder that behind all the success stories (and not just in the fine arts) lies a black undertow of trauma, suffering and profound loss, which, for all its darkness, may well – paradoxically – have acted as a powerful spur to creativity.

Albert Reuss, Fence and Tree 1948, oil paint on canvas, 30.5 x 40.6 cm

© Estate of Albert Reuss, collection of Newlyn Art Gallery, photo: Steve Tanner

Monica Bohm-Duchen is a freelance art historian and the initiator of Insiders/Outsiders: Refugees from Nazi Europe and their Contribution to British Culture, a nationwide arts festival that will run throughout 2019 and is accompanied by a book published by Lund Humphries.