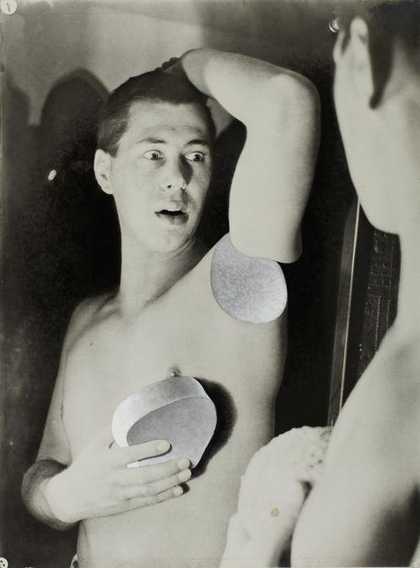

Herbert Bayer Humanly Impossible (Self-Portrait) 1932 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © DACS 2016

We’ve created an A–Z guide because as modernist photographer László Moholy-Nagy once wrote; ‘knowledge of photography is just as important as that of the alphabet’.

Though invented in the 1830s, it wasn’t until the 1920s that photography came into its own as an artistic medium. Photographers began to embrace its social, political and aesthetic potential, experimenting with light, perspective and developing, as well as new subjects and abstraction. Coupled with movements in painting, sculpture and architecture, these works became known as ‘modernist photography’.

A is for Alfred Stieglitz

Photographer, art dealer and publisher, Alfred Stieglitz is credited as one of the leaders of American modern photography in the early twentieth century. Revolutionary in his portrayal of still life and technical mastery of tone, Stieglitz called for photography’s acceptance as an art form, as well as introducing avant-garde European artists such as Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brâncuși and Francis Picabia to America’s art scene. Influenced by new developments in art, Stieglitz moved away from a more decorative, soft-edged ‘pictorialist’ style. His work The Steerage 1907, with its sharp focus and striking angles is often considered as a benchmark for the beginnings of modernist photography.

B is for Bauhaus

The Bauhaus was one of the most influential art and design schools in the twentieth century, a seedbed of nearly all the art forms we now think of as modernist. The Bauhaus existed in three cities: Weimar 1919–1925, Dessau 1925–1932 and Berlin 1932–1933, where it closed due to pressure from the Nazis. Its aim was to bring art back into contact with everyday life, so design and craft were emphasised as much as fine art.

The Bauhaus embraced new technologies. This was particularly evident in the photography department, where the celebrated artists László Moholy-Nagy and Walter Peterhans encouraged students to use their cameras to imagine new worlds and focus on experimentation such as close-ups and photomontage. As Moholy-Nagy stated ‘everyone is equal before the machine … there is no tradition in technology, no class-consciousness’.

C is for Camera Work

Published by Alfred Stieglitz from 1903 to 1917, the photographic journal Camera Work featured some of the most important modernist photographers of the early twentieth century. Stating that he wanted to create ‘the best and most sumptuous of photographic publications’, Stieglitz published the journal with the aim of promoting photography as an art form in its own right. The final issue celebrated photography as the ‘first and only important contribution thus far of science to the arts’.

D is for Dora Maar

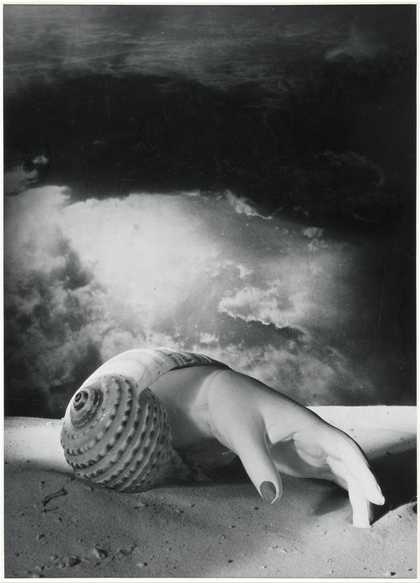

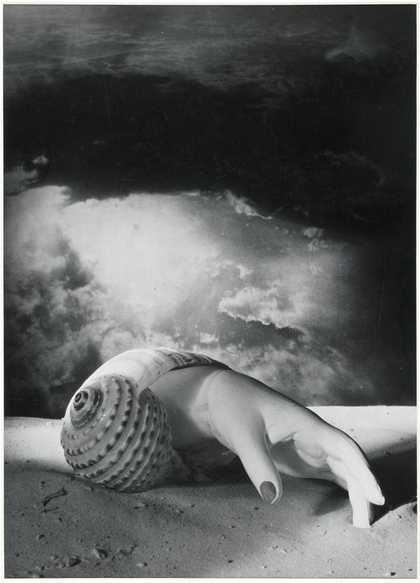

Dora Maar Untitled (Hand-Shell) 1934 © Estate of Dora Maar / DACS 2019, All Rights Reserved

Dora Maar was a twentieth century photographer and painter. She worked across art genres and techniques including photomontage, darkroom experiments and abstract landscape paintings. During the 1930s, she built a successful career as a photographer in fashion and advertising, and travelled to Europe to document harsh social conditions. Her surrealist photographs, collages and photomontages made her one of the few photographers to be included in surrealist exhibitions. Her political beliefs had brought her close to the movement.

In late 1935 or early 1936, Maar met Pablo Picasso. Their relationship had a huge effect on both their careers. Maar documented the creation of Picasso’s most political work, Guernica 1937, encouraged his political awareness and educated him in cliché verre, a technique combining photography and printmaking. Picasso painted Maar in numerous portraits, including Weeping Woman 1937 and encouraged her to return to painting.

By 1939 Maar had withdrawn from photography to concentrate on painting. These often reflect her environment. In Paris during the Occupation, she made still lifes with sombre colour palettes. In the south of France, her landscapes became more abstract. Maar returned to the darkroom in her seventies, experimenting with hundreds of photograms (camera-less photographs). Maar died on July 16, 1997, at 89 years old. Throughout her life she created a vast and varied range of work, much of which was only discovered after her death.

Dora Maar is on at Tate Modern 20 November 2019 – 15 March 2020. Book now.

E is for Edward Steichen

Edward Steichen A Bee on a Sunflower c.1920 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © The Estate of Edward Steichen/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016

Alongside Stieglitz, Steichen also pioneered the modernist photography movement.

Following the First World War, Steichen moved away from his previously pictorialist style and began to experiment with various techniques. He adopted a modernist style, incorporating elements of abstraction and a highly defined clarity within his images. These early experimentations helped to redefine and strengthen the appeal of photography.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Steichen worked as a fashion photographer for American Vogue and Vanity Fair. His soft-focus portraits of celebrities including, Gloria Swanson and Clara Bow, captured a romanticised vision of Hollywood; a mode still used today. Described by Vanity Fair’s editor Frank Crowninshield as one of the ‘world’s greatest living portrait photographers’, Steichen became the world’s highest paid lens-based artist.

F is for false cameras

Mounting a false brass lens to the side of his camera, American photographer Paul Strand would photograph his subjects using a second working lens hidden under his arm. Known as the candid camera technique, this allowed him to capture people without their knowledge. As the photographer describes, he wanted to make ‘portraits of people the way you see them in New York parks – sitting around, not posing, not conscious of being photographed’.

From Jewish patriarchs to Irish washerwomen, Strand’s street photography offered a drastic alternative to posed and formal studio portraits.

G is for Group f.64

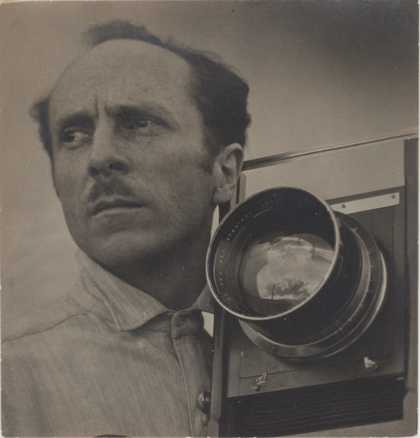

Tina Modotti Portrait of Edward Weston with his Camera, Mexico 1923 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection

Founded in the 1930s, Group f.64 was a group of eleven photographers, including Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston, who were united by their desire to photograph life as it really is. Characterised by a clear, sharp-focus aesthetic, their style was at odds with the romantic methods of manipulating images during or after printing, fashionable at the time. Instead they focused on accurately exposed images of natural forms and found objects.

As cameras became more sophisticated, different effects could be achieved quite simply. By closing the aperture on the lens (like the iris of an eye), the focus of a picture was sharpened. The name f.64 refers to the smallest aperture on a camera, used by the group because it provided the greatest depth of field, allowing for much of the photograph to be in sharp focus. Perhaps the overarching vision of the group was their belief in the camera as a passive observer of the world, better able to depict life as it really was because it did not project personal prejudices.

H is for human form

Edward Weston Nude 1936 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © Edward Weston 1981 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

The effects of the First World War saw a dramatic change in attitudes towards the human body. Previously depictions of the human body were largely either for academic study, used as reference points for painters and draughtsmen, or in pictorialist compositions in which the female body was typically highly aestheticised.

This was reflected in artists’ and photographers’ depictions of the human form. Modernist photographers experimented with cropping and framing a single body part, distorting and accentuating its curves and angles. In 1936, the philosopher Walter Benjamin compared the camera to a surgeon’s knife, able to permeate the body by splicing it into fragments. As a result the body was often depersonalised, instead appearing as something unfamiliar, often almost plant or landscape-like.

I is for icons

Irving Penn Salvador Dalí, New York 1947 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © The Irving Penn Foundation

The 1920s and 1930s saw a close relationship between celebrity portraits and fashion. Modernist photographers including Irving Penn, Man Ray, George Platt Lynes and Edward Steichen, photographed artists, writers, musicians and Hollywood stars including Salvador Dalí, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein and Jean Cocteau. Featuring in magazines such as Vogue, Vanity Fair and Harper’s Bazaar, these portraits were instrumental in shaping the celebrity’s public image. Rather than focusing on the sitter’s occupation and status, the images were innovative in their pose, composition and cropping, as seen with Penn’s corner portraits. Presenting well-known figures in unexpected or even abstract ways created iconic images rather than mere likenesses.

J is for juxtaposition

Tina Modotti Bandelier, Corn and Sickle 1927 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection

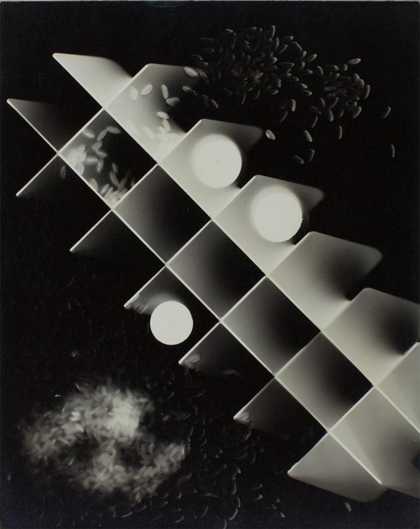

Margaret de Patta Ice Cube Tray with Marbles and Rice 1939 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © Estate of Margaret de Patta

Modernist photographers enjoyed bringing together objects to reveal or create relationships between them. This can be seen in Tina Modotti’s Bandolier, Corn and Sickle 1927 or Margaret de Patta’s Ice Cube Tray with Marbles and Rice 1939. The result creates jarring or stricking compositions and heightens the texture and surface of each object.

K is for Kertész

André Kertész Underwater Swimmer 1917 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © Estate of André Kertész/ Higher Pictures

Hungarian-born photographer André Kertész is known for his ground-breaking use of experimental camera angles and contributions to photojournalism.

Determined to establish a freelance career, he moved to Paris in 1925, gaining commercial success by publishing his photojournalistic work in magazines and newspapers across Europe. While influenced by the theories of surrealism and dada, he maintained an observational approach to photography, which he used primarily as a medium for documenting everyday urban life.

After being injured in the First World War, Kertész took up swimming while recovering in hospital. It was there that he first noticed the distortions that water creates on the body. Underwater Swimmer 1917 is the first of many distortions that Kertész took throughout his career and is credited by British artist David Hockney as the inspiration for his Californian swimming pool paintings.

L is for Leica

Released in 1925, the Leica camera was one of the ground-breaking technical innovations that expanded the development of photography during this period, revolutionising street photography in particular. It used flexible 35mm film – adapted from cinema film – stored on a roll. With a range of film speeds, it could capture movement and adapt to different lighting conditions, making it the ultimate handheld camera. Cheap, lightweight, and portable, the camera provided the opportunity for people to freely document their own lives. Not only did this see an increase in the popularity of snapshot photography, but also the rise of the amateur photographer.

M is for Man Ray

Man Ray Glass Tears 1932 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © Man Ray Trust/ ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2016

Man Ray’s artistic career spanned painting, sculpture, film, prints and poetry, working in styles influenced by cubism, futurism, dada and surrealism. In 1930 he said that ‘painting is dead, finished’, and moved towards photography. He is perhaps most recognised for his use of the photographic method, solarisation and using photograms (developing directly onto photographic paper rather than onto film) which he dubbed as ‘rayographs’. Creating surreal and experimental work, often of famous figures such as Lee Miller and Dora Maar, Man Ray became a key figure within modernist photography.

N is for New York

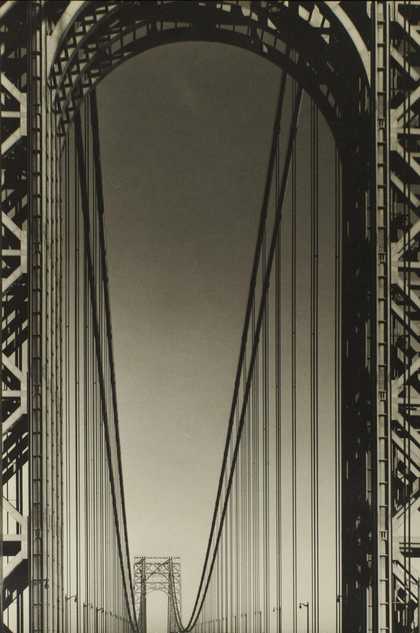

Margaret Bourke-White George Washington Bridge 1933 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © Estate of Margaret Bourke-White/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

During the 1910s, New York was busy with people, carriages, cars and soaring skyscrapers and became the recognised symbol of change and modernity. Rejecting formal Victorian images, modernist photographers embraced crisp lines, abstraction in form and sharp focus, making the changing city the perfect subject. As Stieglitz commented ‘my New York is the New York of transition’.

Due to this, the city played a key role in modernist photography. From its radical architecture to its varied population, it inspired many modernist images and served as a creative hub for many of its photographers.

O is for originality

The enemy of photography is convention, the fixed rules ‘how to do’. The salvation of photography comes from the experiment

László Moholy-Nagy, c.1940

Modernist photographers sought to challenge the preconception that photography could not rival painting. They highlighted the medium’s potential for originality, approaching it with a more experimental attitude and playing with ideas of abstraction. This attitude saw photographers harnessing ‘mistakes’ such as distortions and double exposures, and physically manipulating the printed image, cutting, marking and recombining photographs to create an often surprising, playful and radical image.

P is for Photo-Secession

Many historians date the beginnings of modernism in photography to the Photo-Secession, a group of American photographers founded by Alfred Stieglitz in 1902. Members included Edward Steichen, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Gertrude Käsebier and Clarence H. White, who all placed great importance on fine photographic printing and used techniques which mirrored paint and pastel. Their main ambition was to position photography as more than a popular pastime or commercial pursuit, and rather as a fine art. The results were exhibited in their New York gallery, The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, later known simply as 291.

Q is for quotes

Here are a few of our favourite quotes by modernist photographers:

It has never been my object to record my dreams, just the determination to realise them

Man RayThe illiterate of the future will be the person ignorant of the use of the camera as well as the pen

Laszlo Moholy-NagyPhotography is a major force in explaining man to man

Edward Steichen

R is for relationships

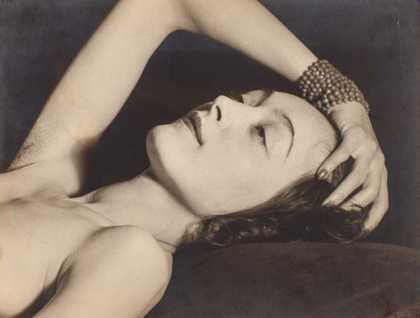

Man Ray Nusch Eluard 1928 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © Man Ray Trust/ ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2016

As well as formal artistic groups and schools, many informal collaborations thrived during the modernist period. These included both professional and personal relationships. Often the subtleties of these creative networks can be seen within portraits taken by the modernist photographers as different connections emerge. For example, student and teacher (Berenice Abbott and May Ray), muse and artist (Kiki De Montparnasse and Man Ray) and there are many instances of lovers (Edward Weston and Tina Modotti, Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe, Man Ray and Lee Miller).

S is for Straight Photography

Modernist photography celebrated the camera as an essentially mechanical tool. Critic Sadakichi Hartmann’s 1904 ‘Plea for a Straight Photography’ heralded this new approach, rejecting the soft focus and painterly quality of pictorialism and encouraging straightforward images of modern life. Common characteristics of modernist images include clean lines, sharp focus and repetition of form.

T is for technology

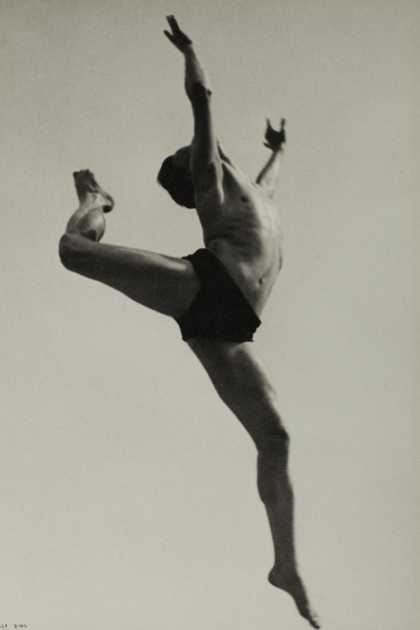

Ilse Bing Dancer, Willem van Loon, Paris 1932 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © The Estate of Ilse Bing

After the First World War, technological advances became seen as vehicles of progress and change, to put the horrors of the 1910s behind them. Photography’s association with technology and science meant that it appealed to avant-garde artists wishing to break with convention and explore modern life.

Developments in camera technology during this period also enabled photographers to capture movement. Previously, motion had only been suggested by the blurring effect of a long exposure or presented through series of static frames. Thanks to increased shutter speeds and roll film, photographers were able to easily capture the body in action. Figures were no longer forced to hold a pose. Instead they’re removed from the studio and shown jumping, running and suspended in mid-air, with a clarity impossible for the naked eye.

The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh.

Edward Weston, 1924

U is for Umbo

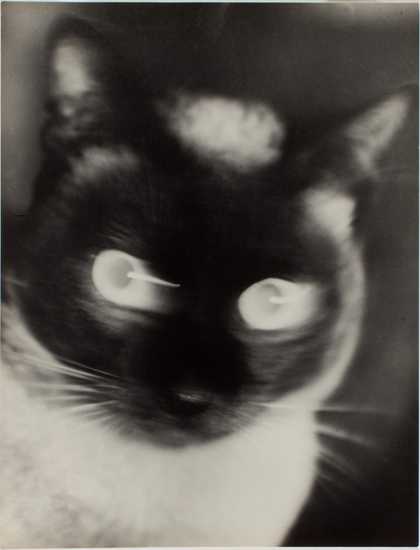

Otto Umbehr “Katz” - Cat 1927 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © Phyllis Umbehr/Galerie Kicken Berlin/ DACS 2016

After studying at the Bauhaus, Otto Umbehr took on the artist name of Umbo and moved to Berlin. Focusing on images of the city and its bohemian society, his work quickly became part of Germany’s avant-garde photography scene.

In 1928, Umbo became one of the founding members of the first cooperative photojournalism agency, Dephot. The agency was later closed by the Nazi regime. In 1943, Umbo’s Berlin archive, containing between 50,000-60,000 negatives, was destroyed in a bombing. Very few of his photographs from the period survive today.

V is for viewpoints

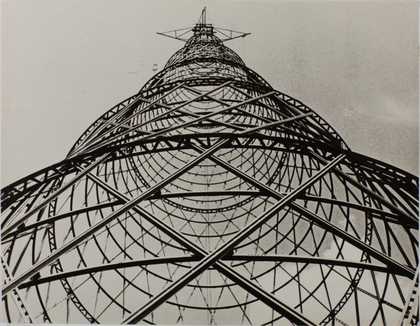

Alexander Rodchenko Shukov Tower 1920 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © A. Rodchenko & V. Stepanova Archive, DACS, RAO 2016

Increased availability of the handheld camera in the 1920s enabled modernist photographers to explore viewpoints that flattened space and emphasised shape, tone, highlights and shadows. Championing what they referred to as ‘bird’s eye’ and ‘worm’s eye’ views, they experimented with angles and perspectives to create a distorted reality.

Do you understand now that the most interesting viewpoints for modern photography are from above down and from below up, and any others rather than belly-button level?

Aleksandr Rodchenko, 1928

W is for Walker Evans

Walker Evans Christ or Chaos? 1946 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection

American photographer Walker Evans was instrumental in establishing the American documentary photographic tradition. Working alongside photographers Dorothea Lange and Arthur Rothstein, among others, his depictions of rural and small-town life not only chronicled the realities of the Great Depression, but also positioned him as a key documentarian of the period. His photographs appeared in multiple publications, and in 1938 the Museum of Modern Art, New York, held a retrospective of his work: American Photographs.

X is for x-ray-like images

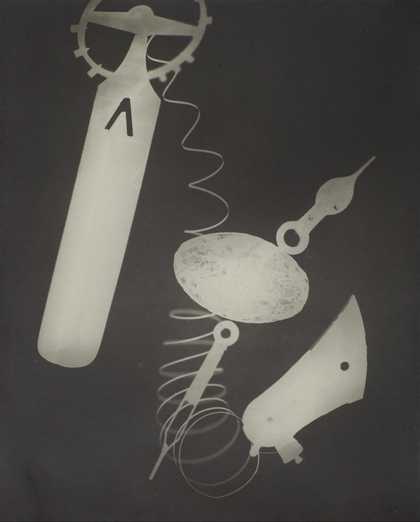

Man Ray Rayograph 1923 The Sir Elton John Photographic Collection © Man Ray Trust/ ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2016

One of the darkroom processes practised by modernist photographers was the photogram. The process dates back to the development of ‘photogenic drawing’ by William Henry Fox Talbot in 1834. The technique involves placing objects onto the surface of a light-sensitive material, normally paper or fabric, and exposing it to light, revealing a negative representation of the object to create an x-ray-like image.

As attention shifted to lens-based techniques, the process fell out of fashion. However the beginning of the twentieth century saw a resurgence in its popularity and modernist artists repackaging the process under various names. Christian Schad’s work became known as ‘schadographs’, Man Ray coined the term ‘rayograph’ and László Moholy-Nagy adopted ‘photogram’. Simple to produce, this pared-back approach to photography had radical results.

Y is for Yamawaki

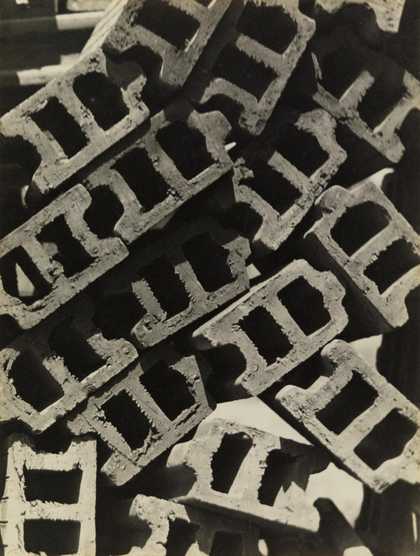

Iwao Yamawaki Untitled (Composition with bricks, Bauhaus) 1930–2 Tate

Iwao Yamawaki Untitled (Modernist architecture) 1930–2 Tate

Born in Nagasaki, Japan, Iwao Yamawaki studied architecture at the Tokyo School of Arts, after which he joined a construction company. At the same time he began experimenting with a 35mm camera. In 1930 he interrupted his architectural career and enrolled at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany, where he concentrated on photography. He engaged in techniques and processes promoted by László Moholy-Nagy such as combination printing, photograms and diverse viewpoints. In his travels throughout Europe, he documented details of modernist architecture and design. Although he returned to architecture once back in Tokyo, he continued to spread the Bauhaus philosophy as a teacher and through articles and exhibitions.

Z is for zoooooooooom

From cropping and zooming, to distortion and framing, modernist photography saw a radical shift in how we capture the world around us. Its lasting effects and spirit can be seen within the works of many contemporary photographers.