The French call flagellation le vice Anglais, because our famously guilt-ridden attitude towards sex has supposedly given cross-Channel trippers a grand goût for rope and rod. Whether we exhibit this proclivity more than the nation that gave us the Marquis de Sade and Georges Bataille is a matter for sociologists, but it is certainly true that English visual art includes a wealth of bondage imagery. The late Victorians have plenty to offer us, especially when it comes to portable prints, photographs and book illustrations - the most prominent artist being Aubrey Beardsley, the master of the whiplash line. But while the period around 1900 was a golden age for images of le vice Anglais, many other examples exist among the cartoons and prints of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, including Plate 3 of The Harlot’s Progress 1732, where a birch rod is strategically placed over the bed.

However, we have to travel back to the Elizabethans to find the first and, arguably, the greatest connoisseurs of bondage imagery. They made pioneering visual poetry out of bondage because, far from being a mere private peccadillo, it was a symbolic instrument of state, its imagery permeating the highest reaches of society. There are two key reasons for this grand efflorescence: first, the presence on the throne of an omnipotent Virgin Queen, on to whom all kinds of male submission fantasies were projected; and secondly, the vogue for the poetry of Petrarch (1304–1374), which wallows supremely in the pains of love.

The most important and possibly the first example is Antonis Mor’s magnificently brooding half-length portrait of Sir Henry Lee 1568. A well-born landowner and diplomat/spy, Sir Henry (1533–1611) was one of the most cultivated men at the court of Queen Elizabeth I. He had been an expert in the language of love from childhood, as he had been brought up in the household of his uncle Sir Thomas Wyatt, the most distinguished Petrarchan poet in England and the first writer of sonnets in English. Sir Henry was for many years the Queen’s Champion for the Accession Day Tilts, which meant he had to organise the ceremonial jousts that took place annually on 17 November, the day of her accession to the throne in 1558. These tournaments, with their triumphal entries of knights attended by squires, pages and liveried servants, followed a pattern that was popular throughout Europe in the second half of the sixteenth century. Lee had to lay down his gauntlet in the queen’s defence before each tilt, dress up in symbolic costume and give wittily romantic speeches. The fundamental principle of such tournaments was that the more the knight endured for his lady, the more he deserved her pity and love.

In Mor’s beautifully painted portrait, he wears her majesty’s personal colours, black and white. However, we don’t know if it was created in homage to her or to some mistress – and there is no hard evidence that his relationship with the queen was ever physical. The picture remained in Lee’s possession at his ancestral seat in Oxfordshire, Ditchley Park, so it may equally have been an idealised self-image as a servant of Eros. What makes the portrait especially interesting is the peculiar and unprecedented way in which the thumb of his left hand is inserted into a ring suspended from a red cord hanging round his neck. Lovers frequently exchanged rings, and as the size of finger rings could not then be easily adjusted, the recipients often hung them from their neck, or tied them to their sleeve. Later on, women fixed them to the fingers of their left hand with long black strings looped seductively around their wrist, making a striking fishnet contrast to their white skin. Lee’s ring, set with a ruby, is a clear symbol of the lover’s willing enslavement. Not only is his thumb jammed in it, but it is suspended by a (blood) red “noose”, pulled tight around his neck. In Petrarchan poetry, cupid was often blamed for causing a disappointed lover to hang himself, and this dismal outcome is maybe alluded to here.

Lee’s impudently phallic thumb might as well be in a thumb-screw (a standard instrument of torture at the time), and his pinioned left arm looks as though it is in a sling. The poet Christopher Marlow would subsequently write an elegy to a ring he himself had given to his mistress. He imagines that he becomes that ring, and as she wears it on her finger, he eventually gains access to her more intimate zones, whereupon it is transformed into a dildo. Here, Lee might be imagining that the ring is a gleaming vagina dentata, the cause of the most exquisite pain. One thinks too of Shakespeare’s Cleopatra, for whom “the stroke of death is as a lover’s pinch, which hurts and is desired”. Sir Henry wears five more rings on his left hand and arm. A gold one is placed on the fourth finger and two more on the third. Two additional rings are tied round his left arm and wrist by red cord, echoing the gold pattern of “true lovers’ knots” that adorns his white sleeve. All the while, his right arm hangs limply by his side, and is depicted only above the elbow. This makes him seem even more defenceless. It has been said that the portrait shows him “staring out full of confidence”, but his lips are surely pursed with grim determination. Years later, he would appear as the Enchanted Knight at the Accession Day Tilts, unable to do battle because, as a contemporary document puts it, “his arms be locked for a time” after a spell cast by “the Queen of the Fairies”.

What is most specifically Petrarchan about the portrait is the fact that Lee’s left side is the focus. Since the heart is located on the left of the chest, and because most people’s left arm and leg are weaker than their right, Petrarch romanticised this side by making it the ultra susceptible seat of the emotions. When cupid shoots his arrows, he aims at the left of the victim’s body, and it is this side that is always being transfixed, scarred, scratched, mutilated, numbed and made lame. It was traditionally thought that a vein led directly from the heart to the fingers of the left hand, so wedding rings and lovers’ rings had to be worn here: the red cord in which Sir Henry is entwined, and which seems to emanate from his left thumb, may be thought of as a vein with a direct line to his heart.

Marcus Gheeraerts II

Portrait of Captain Thomas Lee (1594)

Tate

The left side is again the focal point of another great painting commissioned by Sir Henry – Marcus Gheeraerts II’s full-length portrait of his politically controversial cousin Captain Thomas Lee 1594. The captain is depicted with a scar on his left hand and a bare left leg pushed forward. The scenario is similar to that expressed in a sonnet by Petrarch that was translated by Sir Thomas Wyatt. In Complaint upon Love, to Reason, the poet remembers his youth:

And thus I sayd: once my left foote, Madame, When I was young, I set within his [Love’s] reigne: Wherby other then fier[ce]ly burning flame I never felt, but many a grievous pain.

The portrait, with its advanced left foot, suggests that only love (presumably for the queen) guides the captain’s actions, and that this love has brought him great suffering.

Sir Henry confirmed his lifelong status as an all-too willing victim in the celebrated Ditchley Portrait 1592, which hangs beside Mor’s picture in the National Portrait Gallery. Also painted by Gheeraerts, it was commissioned to celebrate the queen’s two-day visit to Ditchley in 1592, which featured elaborate theatrical entertainments. Sir Henry was now living at Ditchley with his mistress Anne Vavasour, a ménage-à-deux of which her majesty initially disapproved. The visit marked her forgiveness of him for becoming a “stranger lady’s thrall”. The portrait of the queen is the largest and grandest ever painted, and its elaborate iconography must have been devised by Sir Henry to show his loyalty and subservience. She bestrides a giant map of England in full regalia, her feet planted on Oxfordshire, her heel near Ditchley. The sky behind her left shoulder is, as it were, emotional – it is tempestuous and rent by lightning. To her right it is bright and sunny. A sonnet inscribed on the canvas, which must have been devised by its patron, explains that the sun reflects her glory and the thunder her power. In his political and sexual relations with women, Sir Henry evidently relished a bit of both.

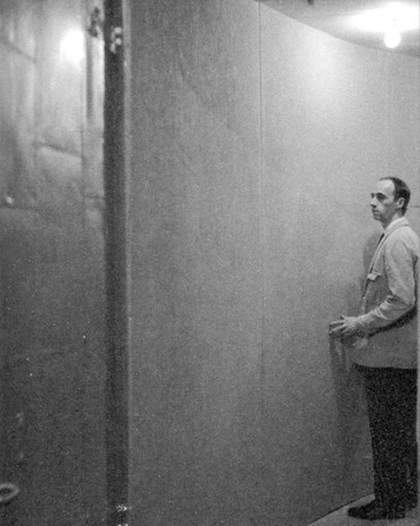

Are there any modern successors to Mor’s portrait? Certainly modern psychology has confirmed the left side as the emotional and confessional side of our being, and the left hand as being more expressive of our emotions as it has more crease-lines. In the 1940s the psychologist Werner Wolff experimented with the facial halves and found that the left of your face is more easily recognised by yourself, whereas the right is better recognised by others, concluding that the left side represents our underlying wishes and desires (the “wish face”), while the right bears the individual expression that the person exhibits in his or her daily life (the “public face”). The American artist Robert Morris may have had these ideas in mind when he made his self-portrait publicity poster for his 1974 New York exhibition Labyrinths-Voice-Blind Time. He photographed himself from the waist up, wearing nothing but a Nazi helmet, sunglasses and a manacle around his left wrist, chained to a spiked neck band. Lit from his left, the whole of the right side of his body and face is cast into deep shadow. When Morris made it, he was intrigued by psychoanalytical ideas concerned with the liberation and repression of the self. Thus, it made perfect sense to unapologetically foreground what we might term his wish side. Seeing this modern Mars who has been – or is about to be – tamed by Venus, brings to mind some lines written by the Venetian Petrarchan poet Pietro Bembo almost five centuries earlier: “I moved my foot in such a way that your beautiful eyes, my Lady, could feast on my whole left side.”