Rebecca Warren in her east London studio, July 2017

photo © Hugo Glendinning

LAURA SMITH Your work in sculpture is so varied, from your clay and bronze figures to your use of neon and collage, and the miniature worlds of your MDF vitrines. How does all of this begin?

REBECCA WARREN I don’t really know where it comes from. From a sort of strange nowhere. Then gradually something comes out into the light. There are impulses, half-seen shapes, things that might have stuck with you from decades ago, as well as more recently. It’s all stuff in the world going through you as a filter...

LS So, how does this filter deal with such a broad range of influences? When I look at your work I am thinking about Willem de Kooning or Minnie Mouse simultaneously, or about Alberto Giacometti and The Michael Zager Band (whose 1977 disco hit Let’s All Chant you’ve used as the title for one of your recent sculptures).

'I realised that I didn't have to fear things that I liked. I didn't need permission to like them.'

RW Things of any kind come up from below – much more than they are dropped from above by me. That’s how they have to work, otherwise they’re add-ons, dubious justifications... You discover what bits of the world keep nagging at you and fascinating you because they won’t leave you or your work alone. In my case, there are lots of things, including artists’ works from the fairly distant and recent past – Rodin, Picasso, de Kooning, etc. And there have been Helmut Newton’s photographs and Robert Crumb’s cartoons... and a whole lot of other stuff – the New York Dolls, Bowie... The Michael Zager Band’s Let’s All Chant probably surfaced because of its insane glam – overcooked to an unusual degree: ‘Your body, my body, everybody move your body...’

LS Yes, and these things often find their way into your studio, physically – from a picture of an enraged-looking Maria Callas to a photograph of a cat by Peter Fischli and David Weiss on the cover of Parkett magazine. What’s the importance of surrounding yourself with these images or objects in the place where you work?

Rebecca Warren's east London studio, July 2017

photo © Hugo Glendinning

RW I collect pictures and notes that have some potential, or are funny, or help rather than hinder. The studio is where the mess coagulates into certain kinds of realities. Nothing else happens in there, which makes a studio quite a strange place in the general run of the world, like a slightly crazy shrine to your own thought processes. The Parkett cover was a turning point for me, because when I first saw it I realised that art could be a picture of a cat standing on a rainy pavement. I realised that I didn’t have to fear things that I liked. I didn’t need permission to like them. I had to unlearn the 80s Goldsmiths (where I did my BA) ethos, where we were supposed to believe in a certain kind of conceptualism that proved itself to be detrimental to creative thinking and action. I would never put pictures on my studio walls in case they were wrong! When I met artist Fergal Stapleton (during my MA at Chelsea), he told me that I could start with the material itself, and begin my relationship to some kind of inchoate idea or impulse in that way. I could choose a material, and the art would tell me what it might be as it developed in that material. This was a crucial breakthrough.

LS Could you say something more about your relationship to the materials you use – clay, bronze, steel, pompoms, paper, neon. What is your attraction to each material and how do they relate to one another?

Rebecca Warren's east London studio, July 2017

photo © Hugo Glendinning

RW I have always varied materials in order to keep things open, and not get stuck. Sometimes I use paper in collages and constructions. I like impermanence, lightness. There’s also an element of early learning when using paper – of scribbling, tearing, discarding. It’s nice to bring those things to the centre sometimes.

I first used neon in collaboration with Fergal Stapleton in the early 90s. We didn’t want to use it in a way that stuck too closely to its normal use – making words, declarative phrases (as those who immediately followed us – into the exact same neon shop! – did). We liked its other qualities, as a material, an element in a field. I still use it like this. At first I couldn’t afford it, so I would use bits they threw out, which for some reason was mainly the letter O. So a lot of my early vitrines had Os in them. Neon glows and spreads the colour. Where that colour ends is hard to define. That’s a thing I like. I often paint the neon glass, or half-obscure it with other elements in a collage or a vitrine. It’s a strange material, half-seen, even when you look straight at it. Its nature is incidental, mystical light.

Steel has its unshakeable macho connotations – but that’s not all it’s got. I like to paint it sometimes, to mess about with it, to put a pompom or some other little element on it. It’s a ground and it’s the thing itself. It’s heavy and dark and in the way and very present – like a bad shadow.

You can polish nice highlights into bronze. If you paint it, it becomes made of paint throughout – or the paint has form – or the two impact each other at odd mental angles.

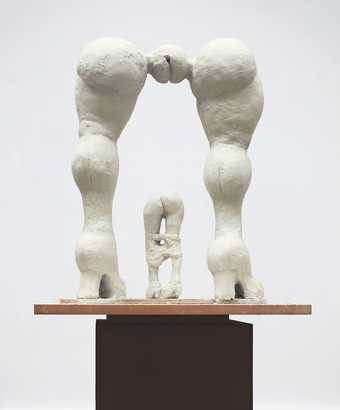

Rebecca Warren, Helmut Crumb 1998, reinforced clay on two stacked, painted MDF plinths, clay: 55.9 x 50.8 x 38.1 cm

© Rebecca Warren, courtesy the artist and Maureen Paley

Some of my work is made to be cast in bronze, some is made to stay as clay. I first used clay in 1998 with Helmut Crumb followed by my show The Agony and the Ecstasy at Maureen Paley, London in 2000, which consisted predominantly of clay works. Using clay was extremely unfashionable at that time. People laughed at me and thought I’d lost my mind. But I knew I had found something quite powerful and real for me.

Pompoms are so gorgeous, why wouldn’t you have them in your art?! Put onto other materials, they destabilise the inherent qualities. They reduce weight. They float, they land. They’re like dustballs. They’re decorative and intrinsic at the same time. When you put any of these things together, if you follow some need in these relationships, they can go off into strange places...

LS You’ve talked in the past about pushing and pulling and manipulating clay, which you then solidify – along with your own fingerprints – in bronze. This feels like something very different to the less conscious, more chance circumstances in which the collages are made. Do different materials change the way you work?

RW It’s all manipulation. The human hand can do a lot of things. Exact levels of consciousness and chance are indefinable. There’s always a tension between doing and being done to – or channelling. It’s all one, since even the most deliberate act is made from the dark unknown stuff beneath the surface of your mind.

LS So is there an autobiographical aspect to your work?

RW I don’t think it can be otherwise. It’s all happening in the machine of your head, the person, from the mess of experience. You can’t make someone else’s art. It is surprising how you can be reminded that you were always going to end up doing this stuff anyway. My mum recently showed me all these drawings I did as a kid of twin ballerinas standing on a box. I had forgotten about them, but there they are in my grown-up art: doubled ballerinas on their shared plinth. Strange!

LS For me, there are also always allusions to various cultural (both high and low) clichés of femininity in your work, which you twist and distort in ways that are pointed, or funny, or exaggerated, or heart-breaking.

RW I like to mix things up, turn things on their heads. I’m not a stickler for thinking there is, or isn’t, a categorical difference between high and low, so I mess around in there too. In the end, you like the things you like, and, if you like the whole of something, that’s noticeable. I like the whole of Rodin and Iggy Pop, for instance, and almost the whole of the Todds (Solondz and Haynes, film directors)... When I was drawn to clay, I was also drawn to Crumb and his way of getting to his own desirable forms without worrying about disapproval. Cartoons boil everything down to essential curves. It was a useful – and risky – place to start when I was trying to get an understanding of my own ideas. I used to worry a lot about meaning and where it should come from. Initially I wanted my work to be robustly female, to push that side of things, and this helped in that it allowed me to make anything at all! Starting out, I was holding onto the idea that I needed these anchors to make things. That’s pretty much cured now and I’ve gone on without any need for these qualifiers. Ultimately, I realised that my brain just doesn’t work like that. I gradually discovered that, for me, art is made from freedom and openness to possibilities. Hopefully the realities in all this and the actual answers to these questions emerge in precise forms in the art that I make.

Rebecca Warren, Let's All Chant 2017, painted steel and pompom, 119 x 340 x 235 cm

© Rebecca Warren, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

LS How do you think these ideas will emerge in what you are making for Tate St Ives?

RW For St Ives, I’ve revisited Let’s All Chant 2017, which is a large, pink steel work. It seemed like it could have another life in another venue. (The earlier version was shown at Matthew Marks Gallery in LA.) I’ve made four new large bronze sculptures. They’re recognisably from a certain family of my work, but there’s always some new form or idea at play. They seem quite pagan, like standing stones. Putting them on the floor without plinths will make them very present in a different way.

Rebecca Warren, Los Hadeans (III) 2017, hand-painted bronze and pompom on painted MDF plinth, bronze: 226 x 100 x 68 cm

© Rebecca Warren, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

I’ve also revisited Los Hadeans 2017, another series of bronze sculptures – painting them differently – and this will be the first time anything from this family has been seen in the UK. I’ve made new clay work and new collages. There are also collages I made a while ago and have never shown till now. It occurred to me that these works are only realised fully once they’re shown. Till then they’re full of a kind of latency – latency peculiar to themselves. I wanted to resist just making giant things for a big room. Everything is always made at its finished size, never scaled up from maquettes. Always hand-eye, hand-eye.

LS Apart from the scale of the new gallery at Tate St Ives, has the location and history of the town affected your decisions when making and thinking about the exhibition?

RW St Ives is at the edge of the land, so it’s like a sort of concentrated sump of all sorts of things – gentility, excellence, bland strangeness – a lot of things. There’s something very pagan in there too. I went there to see how it is, to try and pick up something from it – St Ives’ history, the ghost of Hepworth. It was nice to look again at Hepworth. A continuity of that history is always in play in circumstances as dense as these: here were the post-war modernists, the post-Picassoists, working out and enjoying new possibilities. We’re post that, two and three generations later. Each generation has more to go on – or more to ignore. Once I had sort of taken in St Ives, I tried to forget it... I wanted to avoid pastiche and generalisation. St Ives is quite a mad place in a way. It’s the end of the world, the bottom of the Earth, down and down. The title for the exhibition came to me quite early on – All That Heaven Allows (from Douglas Sirk’s 1955 film of the same name). Optimism and limitation. No matter what, this is as far as you can go.

LS You once said that it takes quite a lot of balls to stand in front of one of your sculptures and say, ‘I made that’. What did you mean by that, and do you still feel the same way?

RW You make the art you make, not the art you think you should make, or the art you wish you could make... There is a point when you have to accept what it is that you actually can do. I think I’m a bit out there on my own with the things I make. I think my level of commitment to the actual demands of the art itself, the forms themselves, is unusual. It can run away with you and you have to accept it. It can take you by surprise and not be the thing you expected. In the early days my sculptures weren’t crated – just wheeled out to the lorries. So there’d be blokey shippers pushing the sculptures by their curvy extremities: many opportunities to be mortified!

It’s all made from what you take in. And you have to make it all from a good unconscious place, not your ego. I have followed the art where it leads. Something in the various scales and general appearances can be quite awkward and so quite worrisome to stand next to and boldly claim them as your own. After all, this is me. This is my mind, my life. They are exposures of my intimate relations to art and the world.

Rebecca Warren's east London studio, July 2017

photo © Hugo Glendinning

Rebecca Warren: All That Heaven Allows, Tate St Ives, 14 October – 7 January 2018.

Rebecca Warren lives and works in London. She talked to Laura Smith, Curator, Tate St Ives. Photography of Rebecca Warren's studio by Hugo Glendinning. An extended version of this interview will appear in the exhibition catalogue, Rebecca Warren: All That Heaven Allows, published by Tate St Ives in October.