Ben Nicholson OM

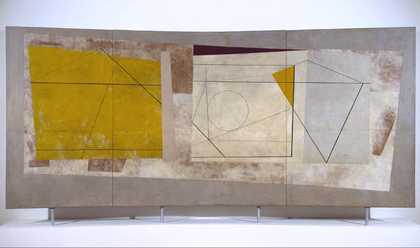

Festival of Britain Mural (1951)

Tate

Understanding Nicholson’s mural

Ben Nicholson’s large Festival of Britain Mural 1951, when it was presented to Tate in 1995, had suffered extensive damage. Not only was this relatively unusual in a comparatively recent painting, but the way Nicholson used his materials, and the nature of the damages, made it difficult to assess how successful treatment would be.

The mural consists of three commercially prepared hardboard panels, pinned to a wooden structure, with a curved middle section and two flat panels, one on either side. The panel to the right is wider than that to the left.

Nicholson was a skilled practitioner and the work is typically well constructed. The paint is well adhered owing to the keying effect of the hardboard’s roughened surface. Sandpaper was probably used, resulting in characteristic swirling scratched lines which the artist exploited in his painting. In places, oil paint was retained by the lines when paint was applied and then wiped off. No general priming layer is visible. Oil paint has been applied in thin, stable layers with the hardboard left exposed or its colour showing through in some areas. Nicholson helpfully noted on the back that he used cadmium yellow, lamp black and lithopone (white) colours.

Conservation challenges

The conservation challenges were many.Most prominent of the damages was a hole near the bottom of the left-hand panel (Figs 2 & 3). It was said that this had been caused by an electrician’s boot prior to the work entering Tate’s collection. Fortunately, the removed piece, albeit in two parts, arrived at Tate along with the mural so that most of the original paint was present for the repair.

Pigeon droppings

More surprising still, were many runs of pigeon droppings down the front of the painting. It seems that the work had been housed in an area at the University of Edinburgh where students ate their lunch; pigeons had gained access through a gap in a roof, perching on the mural and opportunistically swooping down to collect scraps of food.

Abrasions on the surface

Prior to it being in Edinburgh, the mural had been displayed for a time in the Executive Lounge at London’s Heathrow Airport. It seems likely that a line of damages to its surface occurred during this period. These abrasions are at a regular height on all three panels, roughly corresponding to the height of luggage trolleys. The painting had been repaired in the past with patches of fibreglass (in this context not considered conservation grade material).

A general dirt on the surface

In addition to these significant damages, the surface of the painting was generally dirty. It was not immediately obvious what technique could be used to clean it.

In common with most modern paintings, there was no overall protective layer of varnish. Swabbing with water-moistened cotton wool wrapped around the end of a small stick is an effective and frequently used cleaning method. However, in this case, the exposed wood fibres in the hardboard would swell if moistened, forming a roughened, more matte appearance. With no varnish layer present, the unprotected paint was also found to be sensitive to moisture. It was clear from the start that other methods would need to be devised.

Treatment

Cleaning with solvents proved to be effective, but slow. Each area had to be treated numerous times. Any paint that had been covered by pigeon droppings was impossible to save. The droppings are caustic, not only staining the paint, but also causing it to lift off the surface in several places. These damages had to be retouched after cleaning.

Paint was also detaching in other places, notably in the yellow areas and around the nails fixing the panels to the wooden support (fig.5). In places, a filler (covering material) which had originally been applied over the recessed heads of the nails had fallen out and where this was the case, the filler was replaced. Any raised flakes of cadmium yellow paint were made secure.

Repairing the hardboard

The hardboard itself had been damaged, especially at the corners. Treating these losses provided the chance to develop a technique for the repair of the hole in the painting. For this a new filling material was developed. Based on a heat sealing adhesive commonly used in conservation, a recipe was devised that included coconut shell flour. In addition to being a suitable colour, the coconut added a fibrous quality and response to moisture that made it more like hardboard.

Test panels of hardboard to replicate the damaged original were prepared (fig.6). Practising repair methods showed that to be invisible, the front edges of the hole had to be re-aligned. Repeated trials with the replicas and the new filler ensured that the treatment on the actual painting would be successful.

The new filler only becomes sticky when heated. So by heating under weights then leaving the repair to cool, it could be treated many times. Slight adjustments on the original painting continued until little further improvement could be achieved. Fortunately Nicholson’s paint was thin and hard, making the use of heat and pressure possible with no risk of a change in texture. The repair will remain easy to reverse with white spirit and heat if it is necessary in the future. Were cracks to form, it should be possible to remove them simply by re-heating the area.

Encouraged by the good result, the worst of the old fibreglass repairs was replaced.

To reduce movement in the hardboard due to changes in relative humidity a more stable micro-environment was created by fitting a new board behind the original hardboard and packing the space between with polystyrene pieces.

Re-touching the surface

To help the image to be viewed as intended, all visually disturbing damage had to be re-integrated by only applying sufficient re-touching to stop the eye from being distracted by the damage. More thorough re-touching was required to disguise the larger damages, such as the repaired hole.

Most challenging of all to re-touch were the long narrow lines caused by pigeon droppings and water runs. It proved impossible to disguise these completely. If the work is viewed close to, so the overhead lights are reflected in the top part, these dribbles and runs can still be detected.

A new non-yellowing varnish proved helpful. It was mixed with a combination of various grades of rottenstone. This finely ground abrasive material is used in frame conservation and has the property of becoming transparent in varnish. Once dried, the rottenstone particles form a rough surface that appears matte.

A disturbing whiteness in the paint called ‘blanching’ was also present in some areas. Drip marks indicated water was one cause. During cleaning it was noted that the grey areas of paint were particularly prone to this defect. These areas were made less visually distracting by using a grey variety of rottenstone that closely matched Nicholson’s grey; similar treatment was given to two large areas of discolouration on the right panel, where cleaning tests had been carried out before the Mural arrived at Tate.

Preparing the mural for installation

Preparation for installation at Tate Modern involved conservation technicians constructing a shaped plinth to the height stipulated by the collections curator responsible for the display. The curator obtained the architect’s plans for the original installation of the mural in the Riverside Restaurant, London for the Festival of Britain in 1951. The metal struts that hold the work clear of the plinth help to produce an authentic 1950s feel.

Unexhibitable for many years, Festival of Britain Mural 1951 is now fit for display.