Joseph Beuys’s interest in Europe – and particularly in its peripheries – has been widely noted in the available literature on the artist. It appears to have been motivated both by a degree of romanticism and a concern with the knowledge traditions still present in such places; the artist’s friend and former Guardian arts critic Caroline Tisdall has commented, ’He was instinctively drawn to the Celtic fringes, the periphery of Europe, where he believed the old magic was strong’.1 It also stemmed, however, from a degree of pragmatism relating to his desire to disseminate an expanded concept of art, one which sought to stimulate creativity and the development of new ideas about society as forms of sculpture. Claudia Mesch’s study of the artist notes that Beuys’s focus on actively working in areas on the edge of Europe related directly to his desire to stimulate the development of new social forms:

He expressed his interest in founding FIU [Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research] sites in the ‘European periphery’ and in the cities and regions of economically stagnant countries such as Ireland, Sicily or South Africa. In these places, Beuys maintained, present conditions demanded the immediate proposal of new models for various institutions of these societies, and furthermore presented the possibility that new models might be implemented more quickly.2

Somewhat less understood is the artist’s desire to look beyond the European landmass in envisaging the future development of humanity. Beuys conceived ‘EURASIA’ not simply in the sense of the joint European and Asian landmass, but as a utopian concept, using capital letters to distinguish it from the more geographical ‘Eurasia’; the potential of this idea to shift the way in which Europe might be re-imagined reflects the expanded nature of Beuys’s artistic endeavour. The way in which Beuys referred to EURASIA demonstrates that attempts to define his work in relation to fixed borders runs counter to his spiritual project, which related to movement and was, in many respects, in flight from dogmatic intransigence. I will review Beuys’s work in relation to Eurasia here and explore whether the nomadic quality of the artist’s work may have continued relevance today in its attempt to balance Eastern and Western spiritual traditions and work against overly rigid, positivistic forms of thinking.

A Eurasian nomad

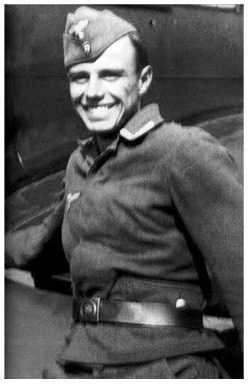

Fig.1

Unknown

Photograph of Beuys as an Officer at the Luftflottennachrichtenschule 2 (Airforce Signal School 2) in Königgrätz, 1942

The dearth of research published on Beuys and Eurasia in the English language, at least until recently, is surprising, since the idea of the combined continental landmass of Europe and Asia informed the artist’s work from as early as the 1950s.3 As with much of Beuys’s art, this concern emerged at least in part from his direct experience of Eurasia during the Second World War, when he travelled across this landmass, principally as a radio controller (fig.1).4 As the curator and art historian Eugen Blume explains in his essay ‘Joseph Beuys: EURASIA', ‘the “Eurasian” [Beuys] had already lived in the massive Soviet Union, a country which stretched from Europe to the borders of Mongolia and China’.5 Beuys’s interest in nomadic Eurasian cultures is indicated in myriad ways in the artist’s work, but perhaps appears most famously in an account Beuys gave of a near death experience he had over Crimea during the war, when the plane he was in crashed, killing the pilot and leaving Beuys critically wounded. He famously and controversially claimed that, though partially unconscious at the time, he was rescued by Tartars, who rubbed him with fat and wrapped him in felt to keep him warm.6

The term ‘Tartar’, like ‘Celt’, has a complex history and relates to a diverse range of communities – historically the Turco-Mongol semi-nomadic peoples of the Northern and Central Asian landmass known as the Tartary, but more recently the term has been used to refer to people speaking Turkic languages. Tartars had certainly settled in the Crimea in the past so on the face of it Beuys’s narrative would seem to stand up in a literal sense. Yet his account was found to have been impossible, since it has been proven that there were no Tartars in the region at the time of his crash.7 The curator Peter Nisbet wrote an informative ‘prehistory’ of the crash narrative in his 2001 article ‘Crash Course: Remarks on a Beuys Story’.8 He refers to a number of critical responses to the account, including its famously scathing dismissal by art historian Benjamin Buchloh as a tale told by Beuys to expiate himself from wartime guilt.9 However, Nisbet argues that it should not dominate understandings of Beuys’s work, which developed and changed in nature throughout his career. Rather, he argues, it clearly related to the artist’s interest in how life stories are shaped and recounted, and to both conscious and unconscious elements of the artist’s lived experience.10 Thus it seems likely that the story constitutes a partially mythologised experience with its own, non-literal validity. Nisbet also reminds us that Beuys’s use of fat and felt was connected as much to the fact that these materials usefully exemplified his theories as it was to his experience of the crash.11

Importantly, in the context of Beuys’s interest in Eurasia, the story Beuys told functions as a compelling image of a wounded individual finding warmth and shelter in a nomadic culture with a non-Western medical and spiritual tradition. In his 2015 film Zeige Deine Wunde (which was named after a work by Beuys and translates as ‘Show Your Wound’), German filmmaker and writer Rüdiger Sünner interviewed artist Johannes Stüttgen, a former Masters student of Beuys at Düsseldorf Academy of Art who worked closely with the artist.12 Stüttgen’s reflection on Beuys is worth quoting in full:

I got to know Beuys as a nomad. That is really how he was. His entire spiritual and mental underpinning was nomadic. His sense of being came out of motion, out of being on the move, of looking for a home on Earth but in certain circumstances not being able to find it. And really his interest in the nomadic in connection to the Mongol people was a form of counter to the polarisation in the West (Occident), it was against the forms of the Middle Ages and dogma. So the nomadic element is essential. And of course he found this nomadic essence again with the Tartars and experienced it in a very real way … I believe however that on the subject of Beuys you will only do him justice in relation to this element if you understand that he...how can I put this...it was a spiritual key that he used to unlock something, the nomadic as a kind of mental essence, an essential description of the spirit, now completely silent, of art.13

Stüttgen observes that Beuys’s anti-Modernist critique arose in opposition to dogmatic developments in thinking that emerged in medieval Europe. This points to a focus on historical developments in Europe’s concept and consciousness of itself. Indeed, observing Beuys’ work Eurasian Staff (Eurasienstab) 1973, discussed further below, curator Nav Haq recognised ‘an intent by Beuys … to dismantle definitions of Europe as the birthplace of western civilization, first used in the eighth century to demarcate the sphere of influence of Latin Christendom, in opposition to the Islamic world and the Eastern Orthodox churches’.14 There is a clear attempt to return to the roots of thinking in the West that had laid the ground for this spiritual split, exemplified by Enlightenment thinking. For Beuys, this path had led to a hyper-rationalism that suppressed the warmth of love, and had gone on to make the perversion of the Nazi regime possible. The only way forward for Beuys, Stüttgen suggests, was through art. The artist’s interest in rekindling a dormant ‘mental essence’ in people was connected to his search for evolution through art, following what he once referred to as the ‘indescribable darkness’ of the recent German – and indeed European – past.15

Fig.2

Joseph Beuys

Eurasians 1958

Photo © Wolfgang Fuhrmannek

A nomadic attitude is clearly in evidence in Beuys’s early sculpture Eurasians 1958 (fig.2). A figure made of wire and tightly wrapped in gauze is placed in the corner of a thick, hand-made felt ground, with a staff-like form protruding from its wrappings. The artist’s use of felt is characteristic; for Beuys, the material’s insulating properties stimulate both a physical and a spiritual (psychological) sense of warming in people. The artist believed that warmth was an energy that could enter into matter but was immaterial and therefore spiritual. Circulating within substances, its properties could be used as a tool to stimulate people to develop new creative forms. Care is needed when referring to the artist’s ideas about actively working with this ‘warmth’ principle through ‘warmth work’ or ’heart thinking’, as interpreters have been inclined to assume that it relates exclusively to feeling and emotion. As the artist and former student of Beuys Professor Shelley Sacks has pointed out, ‘warmth work can be understood as intensive, inner thought work, in which the activated and enlivened will engages with the thought of the heart’.16

Reflecting on Eurasians, Klaus-D. Pohl notes Beuys’s statement that for a long time he had felt he was like a shepherd on reconnaissance, looking after a flock.17 He points out that the work suggests a person pausing in preparedness for movement across a landmass, surmising, ‘The staff will become a companion and pioneering tool for the penetration of space: from east to west – from west to east’. With the Nazi expansionist notion of Lebensraum and Putin’s more recent ideas about Eurasia in mind, a figure suggesting the ‘penetration of space’ across Eurasia must surely elicit caution.18 Lebensraum, the concept that a given race requires a certain amount of space for its survival, was the basis on which the Third Reich pursued an aggressive form of settler colonialism, envisaging the expulsion of most of the indigenous populace of Central and Eastern Europe. Today, Putin’s idea of Eurasia, while advancing valid concerns about the USA’s idea of its global dominance, could be understood as a means to seek a larger empire for Russia. Its related Eurasianism – championed by Putin’s strategic advisor, the philosopher, sociologist and political analyst Aleksandr Dugin – may not be fascism in the strict sense, but its conservatism and revision of fascist themes constitutes a potent and disturbing rhetoric that sees liberalism as a threat to people’s ethno-cultural survival and could, as Alan Ingram argues, be seen as neo-fascism.19 Even if we take on board the gentler, Christological connotations of a shepherd-like figure moving across the Eurasian land mass, the role of the missionary is complex, resounding with the histories of subjugated and violated indigenous communities made literally and figuratively sick by the spiritual intentions of propagators of faith.20 Yet in Beuys’s work, as Stüttgen’s statement implies, there is much to suggest that this sense of a warmth encounter was part of a loving stimulus to genuine dialogue about creativity, an attempt to communicate something essential about the potential of people to shape society rather than the imposition of a particular culture or dogmatic faith tradition.

Siberian Symphony, 1st Movement 1963

Fig.3

Joseph Beuys

For Siberian Symphony 1962

Oil paint and watercolour on paper

Tate AR00655

© DACS, 2019

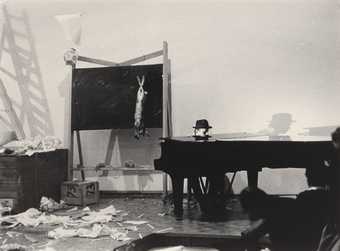

The theme of Eurasia was central to Beuys’s very first action, the symphonic work Siberian Symphony, 1st Movement (Sibirische Symphonie, 1. Satz) of 1963. Planned on paper in For Siberian Symphony 1962 (fig.3), the performance took place at Düsseldorf Kunstakademie, where Beuys was Professor of Monumental Sculpture, as part of an avant-garde music festival for which he opened up the Academy to friends and artists. A piano composition by Beuys was central to the work, which also incorporated elements and harmonies of works by the early twentieth-century avant-garde composer Erik Satie. During the action, Beuys tied up a dead hare and hung it from a blackboard. Electrical wires and pine twigs connected to lumps of clay were used to link the piano to the hare in a kind of circuit, as indicated by the drawing. There is a degree of ambiguity in the drawing for the work. Stephanie Straine notes that the form towards the bottom of the brown packing paper suggests the open lid of a piano21 and a photograph of the 1963 action (fig.4) indicates that the central square may refer to the blackboard itself, with the hare at its centre, adjacent to the piano. Beuys wrote sentences on the board throughout, suggesting that a lesson was being taught and then removed the heart from the dead hare.

Fig.4

Joseph Beuys

Siberian Symphony, 1st Movement 1963

Gelatin silver print

Museum of Modern Art, New York

The artist’s choice of the hare is significant for a number of reasons. In many respects hares do not just symbolise, but exemplify a nomadic spirit. They can move at very high speeds (up to 70 kilometres per hour) and the animal we know as the ‘European hare’ has a far larger range than Europe, moving into central Asia and the Middle East. Thus the hare alludes to the transgression of man-made boundaries and a much broader spatial range than the nation state.22 On the function of the hare in the performance, the art historian and curator Mark Rosenthal writes:

In Sibirische Symphonie 1. Satz (Siberian Symphony, 1st Movement, 1963), Beuys tore the heart from an already dead hare. The hare is an eternal symbol of renewal and rebirth; it evokes a nomadic era honored by Beuys, when cultural divisions between the East and the West did not exist. Although one could argue that Beuys was testing the hare’s powers of renewal, his performance must also be considered a reenactment of a monstrous act committed on a defenceless innocent.23

Here, Rosenthal alludes to the removal of the hare’s heart as a reference to the crimes of the recent German past and this may well be part of its symbolic resonance. Yet clearly the action as a whole does not only point to moments in the past. It has a far larger temporal as well as spatial range, appearing to point to the distant past, the violence of the rupture between Eastern and Western thought, the repercussions of this in the present and finally to a possible future, indicating a potential for evolution. Somewhat contentiously, Beuys made an analogy between the hare, women and the development of human thinking:

[The hare] has a strong affinity to women, to birth and to menstruation, and generally to chemical transformation of blood. That's what the hare demonstrates to us all when he hollows out his form: the movement of incarnation. The hare incarnates himself into the earth, which is what we human beings can only radically achieve with our thinking: he rubs, pushes, and digs himself into Materia (earth); finally penetrates (hare) its laws, and through this work his thinking is sharpened then transformed, and becomes revolutionary.24

Today, we may baulk at the association of hares with women, although the gendered connections Beuys made often related to chemical observations.25 Furthermore, strictly speaking, rabbits dig into the earth, while hares create shallow depressions in which to give birth, or make nests. However, Beuys’s analogy of hares digging themselves into the earth creates a compelling image with which to consider people’s ability to transform and become radical in their thinking.26

Beuys’s reference to ‘the movement of incarnation’ calls up the term as it is understood within a Christian tradition, the notion of Christ as ‘the Word made flesh’. Beuys’s interest in the Logos (Word) is key to the artist’s work. In conversation with Jörg Schellmann and Bernd Klüser in 1970, the artist explicitly expressed the Christological nature of his research as it related to people: ‘How does a word, or I also call it a threshold-sign, become matter? How does it become a real live person?’.27 This concern with human signification is also expressed in the artist’s engagement with the mythic meanings people attach to other animals; in this sense, the hare becomes part of a picture of humanity. In a later conversation with Schellmann and Klüser, Beuys expresses concern that the loss of such ‘connected’ understandings has a detrimental effect on people’s wellbeing and their understanding of their own meaning or, as he puts it, ‘how the human being is meant’.28 Beuys’s understanding of the incarnation as a form of ‘movement’ can be seen in the artist’s theory of sculpture. He saw the Christ principle as the human capacity to act and move things (including thought forms) through ‘warmth’ work, as discussed previously, in order to create a balance between two states – one fixed and crystalline; the other chaotic.

Beuys’s anthropological and Christological perspective was very much in evidence in his ‘Eurasian’ works. Ulf Jensen has commented that Siberian Symphony, 1st Movement ‘was based on a different notion of the relationship between space and time than his colleagues’ [performances]’ and notes that audiences picked up on this.29 Through his action, Beuys introduced movement (Bewegung) as a formative sculptural dimension. When he spoke about movement, the artist was indicating a kind of inner impetus to form stimulated by materials and a desire for transformation. More liturgically, he was indicating resurrection, movement as an agent of art. Sean Rosenthal quotes the artist discussing this: ‘The principle of resurrection, transforming the old structure, which dies or stagnates, into a vibrant, life-enhancing, and soul – and spirit – promoting form. This is the expanded concept of art.’30 Beuys saw it as his role to make people aware of their powers of transformation and found that materials such as fat particularly lent themselves to demonstrating this human capacity and psychological connection to materials. As he put it, ‘my sculpture is not fixed and finished’. In this sense, while Rosenthal may be correct in stating that ’Beuys’s Crimean tale represents a myth of creation, the point from which his art springs’, one might also add that it may teach about everybody’s reconnection to the nomadic spirit of art.31

EURASIA

Beuys’s position was, in part, a confrontation with the recent past – the Nazi Zeit (Nazi dictatorship) in Germany had seen the perversion of knowledge and spiritual ideals that Beuys sought to recuperate and heal. However, very present post-war tendencies were also being addressed. As curator Ann Temkin points out,

Eurasia was a big theme in all of Beuys’s performances and art in general, in that he felt, and remember this is at the time of a divided Germany, that one of the big problems with the post-war world was the division between Asia and Europe and the split between western and eastern ways of thinking.32

In his article ‘Joseph Beuys: EURASIA’, Blume explains:

The will to unite Europe and Asia appeared in 1967 – and was already formulated by the artist in a drawing of 1966 – in the face of a divided Europe and an almost absurd accompanying bipolar division. Let us remember the nuclear arms race on both sides, the political order, the permanent threat that this devastating weapons system would be used and the postcolonial struggle against the European and American powers in Cambodia, Vietnam and other countries of the so-called Third World.33

Indeed, it was in 1966 that Beuys’s engagement with Eurasia developed into a distinct project of political and spiritual reform. Beuys referred to this as EURASIA, in capital letters, to distinguish it as a utopian form. In October 1966, significantly on Reformation Day in Germany, he performed EURASIA, 32nd Movement of the Siberian Symphony, 1963 at the René Block Gallery in Berlin. As in 1963, he hung a dead hare from the blackboard, but this time he drew an image of a half cross on the board, under which he wrote the word EURASIA in capital letters. Discussing this iteration of the work, Blume explains: ‘Beuys told of this common path of man and hare under the halved cross from Europe to Asia, meaning nothing less than the reunion of Western and Eastern humans, the peaceful joining of two great global cultures.’34

Blume also notes the Christological element of the halved cross in the work as it reflected Beuys’s sympathy with Friedrich Nietzsche and theologian and orientalist Paul Anton de Lagarde’s conviction that Paul’s theology was a falsification of the gospel. He explains that with the division of the cross ‘Beuys created a symbol of the spiritual and real division of the world, which now had to be reunited’.35 Beuys’s interest in movement across the massive Eurasian land mass was not an ideal of expanding occupation, then, but of a spiritual holism initiated by an expanded art. For him, this expansion was capable of integrating people and other species in a process and reflecting their historic and ongoing movement in a way that sought to be psychically healthy and stimulating.

Fig.5

Joseph Beuys

EURASIA Siberian Symphony, 1963 1966

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© DACS, 2019

The work EURASIA Siberian Symphony, 1963 (EURASIA Sibirische Symphonie, 1963) 1966 (fig.5) is composed of the materials Beuys used in the Berlin action.36 Temkin observes the hare’s indication of the traversal of great distances and the connection between Beuys’s use of felt in the work and his theory of ‘warmth’ work, but also points out the artist’s note on the blackboard – the degrees of the angles of fat and felt affixed to the poles during the performance, as displayed in the work.37 The temperature noted at the bottom of the blackboard was a direct response to the situation in Berlin at the time of the action; student demonstrators were struggling with the police in anti-Vietnam War demonstrations and Blume notes that, as the political situation heated up, so did the temperature: ‘the temperature had shot up to the limit of what is humanly bearable, 42 degrees Celsius ... The divided world had fallen into a life-threatening fever.’38 In this context, Beuys’s work appeared as a healing balm, but also as a call for a different form of action.

Beuys was concerned by the growing support for Maoist Marxism in the German student movement and wanted to propose an alternative. He looked to EURASIA as a physical and spiritual form for people to work with. In the summer after the Berlin action, he declared EURASIA to be a concrete state form, quite different to that of current state entities, outlining this in a manifesto drawn up on 1 May 1967, perhaps significantly on International Workers’ Day. Following this political statement of intent, Blume explains:

On the 12th May 1967, Joseph Beuys founded the free Democratic Socialist State of EURASIA, which he explicitly did not want to be mixed up with the state structures in the East and West, of which the concepts ‘socialist’ and ‘democratic’ also made claims for themselves. For Beuys, this should ‘provoke a much higher organisational form of people’. A higher organisational form meant a spiritual state of ‘EURASIA’, not a geopolitical structure with conventional administrative and economic forms.39

The influence of anthroposophist Rudolf Steiner on Beuys’s ideas has been widely recognised and Steiner’s ideas about Eurasia greatly informed Beuys’s EURASIA. Steiner advocated cooperation between East and West as a route to greater social harmony.40 His concept of the ‘three-fold social organism’ was conceived in 1917, the third year of the First World War, the massive losses of which, in both human and economic terms, led to myriad discussions on how best to organise social life. Put very simply, Steiner proposed that a purely economy-based solution to social ills was bound to fail. He argued that the economy, the life of the spirit/mind (which he saw as the producer of ideas and therefore ‘real’ commodities) and the law should be kept autonomous, and that the economy and the free life of the spirit/mind should be kept in balance, adjudicated by the law.41 This model constituted neither a capitalist nor a communist position, but a third approach to managing social life. Beuys was also seeking a third way forward beyond these two positions that proposed a different relationship between the economy, the life of the mind and the law. However, it is clear that Beuys developed a model that was very much his own, outlining a higher spiritual form of human organisation which integrated creativity.42

Collaboration with Nam June Paik

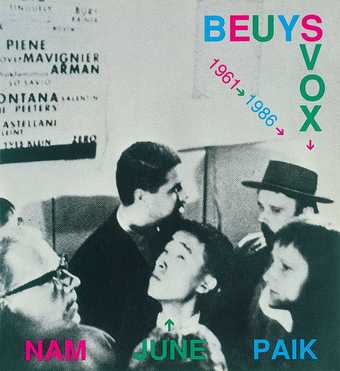

Fig.6

Cover of the catalogue for Nam June Paik’s Beuys Vox 1961–1986, shown at Documenta 8 in 1987

Courtesy Collection Peter Wenzel

© The Estate of Nam June Paik

Beuys’s work on the subject of Eurasia did not develop entirely independently, but rather through collaboration with the American-Korean Fluxus artist Nam June Paik, who Beuys met in 1961. Both Beuys and Paik were involved with the Fluxus movement and its engagement with everyday materials, transforming the relationship between artist and audience, although Beuys was to distance himself from the movement’s anti-art emphasis which conflicted with his interest in art’s anthropological potential.43 Both had been influenced by their particular wartime experiences: Paik, growing up in Japanese-occupied Korea before later escaping to Japan; Beuys, a German growing up under fascist rule. The influence of Paik on the development of the utopian concept of EURASIA is only just starting to be researched in depth and from an Asian perspective. In his PhD thesis, Japanese researcher and curator Shinya Watanabe documents the two artists’ lifelong friendship and work together, noting that Paik cited Beuys’s plane crash in Crimea as the moment they met.44 Like the Tartar story itself, this was not meant literally, but, for Paik, clearly the event united their sympathies and, to refer to the theme of this collection of essays, bridged their respective wartime and spiritual trajectories. Watanabe comments that Beuys and Paik ‘became the first artists to consider Europe (=West) and Asia (=East) one continental culture, and tried to connect them as “Eur-Asia”’.45 Following Beuys’s death in 1986, Paik used a photograph taken the day they met at the Zero Group exhibition in Düsseldorf as the cover image for his memorial work, Beuys Vox (fig.6).

It is clear that both artists shared an interest in Eastern spirituality and non-scientistic healing practices. This is communicated in Beuys’s practice in all its forms, from early drawings in the 1950s to environments (Beuys’s term for installation works) created not long before the artist’s death in 1986.46 Watanabe mentions Paik’s reflections on why the German artist had initially approached him as Paik had voiced them to his assistant, Justin Hoffmann:

In things of Shamanism they are very strong, this had very strong influenced Beuys, the Tatars. Probably he saw me in ‘Hommage à John Cage’ and in 1961 he addressed me as ‘Herr Paik’, because he wasn’t especially famous yet then, and we very quickly got to like each other … Probably he knew what Mongolian shamanism was like, and my ‘Hommage à John Cage’, in hindsight, had something of the same mood about it. You know: Beuys had some prior knowledge about what Mongols do.47

Beuys clearly stated on a number of occasions that he was interested in shamanism as a means to gauge how it could inform future developments relating to people’s relationship to materials and myth, rather than advocating a return to this practice in a strict sense. The artist outlined his position in the following way:

I take this form of ancient behaviour as the idea of transformation through concrete processes of life, nature and history. My intention is obviously not to return to such earlier cultures but to stress the idea of transformation and substance. That is precisely what the shaman does in order to bring about change and development: his nature is therapeutic … while shamanism marks a point in the past, it also indicates a possibility for historical development … So when I appear as a kind of shamanistic figure, or allude to it, I do it to stress my belief in other priorities and the need to come up with a completely different plan for working with substances.48

Yet however emphatic the artist was that his primary goal was to put forward a new ‘plan’, Beuys’s references to the understandings of non-scientistic traditions and Eastern philosophies as balancing forces continues to raise concerns. Indeed Beuys’s – and to an extent Paik’s – Eurasian project has come under criticism for its orientalism, in the sense of constituting inaccurate and stereotyped Western representations of Eastern cultures and people.

In ‘The Utopian Globalists: Artists of Worldwide Revolution 1919–2009’, art historian Jonathan Harris refers to Beuys as ‘the primary mid-twentieth-century utopian globalist artist’ and argues that Beuys used ‘the methods and means of spectacular culture … to generate a “Eurasian”, if not a global, majority in favour of radical socio-political transformation of both western democratic capitalist and Soviet communist social orders’.49 Harris’s primary concern about Beuys’s work is that it constitutes a form of globalism which, he argues, lies in an ‘idealized representation of the creative renewing powers of “eastern” as opposed to “western civilizations”’.50 Harris questions the dualisms on which this representation rests and the degree to which the liturgical meanings of Beuys’s actions were policed, largely by his close friend Caroline Tisdall, rather than being left open-ended. Reviewing what he refers to as the ‘actions which adumbrated Beuys’s “orientalist” perspective’, he argues:

The received, conventional dualisms multiply – the context of ‘intuition’ versus ‘intellect’; harmony with nature and the cosmos versus a dominating rationality and anthropocentrism; spiritual versus materialistic values. Beuys’s actions are portrayed, by himself and his appointed interlocutors, as ritualized narratives that give symbolic form to the unification of the capacities of these divided ‘wests’ and ‘easts’ inside all of us – the human and the animal, the earthly and the other-worldly.51

Harris’s assessment is valid in its concern about the potential of Beuys’s position to perpetuate stereotypes and dualisms. It is also sensitive in its suggestion that Beuys’s model had as much to do with stimulating inner as outer wholeness. However, the degree to which Beuys blindly romanticised the East should not be overstated. The artist developed his expanded notion of art in the context of increasing rigidity of thought in the East as much as the West, and his concern regarding West German student engagement with Maoism indicates that he was just as mindful of the inhumane repercussions of extremism in the East. For Beuys, the medieval rupture of Eastern and Western traditions had suppressed the capacity of myth within both traditions to speak to the transformation of the self and societies.52 Both Beuys’s independent practice and his collaborative work with Paik on the theme of Eurasia confronts damage done to both Eastern and Western people, or Ost and Westmensch, by the schisms initiated by spiritual, geographical and political divisions.

In a sense, then, Beuys was undertaking a form of reparative work and sought creative ways forward through dialogue, intercultural understanding and cooperation rather than proposing a simplistic melding of traditions. Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Antwerp (M HKA) Bart De Baere emphasises that the artist’s aim was not ‘for a complete merger between East and West or for multiculturalism, but rather for the capacity that may be the outcome of mutual understanding and vital openness’.53 Thus, while caution with regard to a certain Orientalism in the work is sage, it could be argued that Beuys faced up to contemporary political circumstances in both the West and the East through his concern with balance, non-positivistic materialism and the promotion of ongoing dialogue in order to face critical issues confronting human beings. The entire emphasis of his practice conveyed the belief that no matter how apparently rigid and static things may appear, they can change. In 1982, Beuys met with the fourteenth Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism and the Tibetan people, who continues to struggle against China’s occupation of Tibet to this day. Watanabe notes that when his aide initially showed him Beuys’s work, he responded ‘Aha, this artist is working on the same thing as we are: impermanence.’54

EURASIAN STAFF, 1967

Fig.7

Film of Joseph Beuys performing EURASIAN STAFF, 1967 at the Wide White Space Gallery, Antwerp, on 9 February 1968

Film by Joseph Beuys and Henning Christiansen is titled Eurasienstab, Fluxorum organum opus 39 1968. The soundtrack is by Henning Christiansen.

Tate TAV 1623F

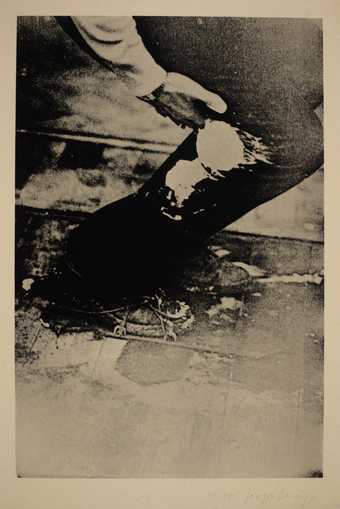

Fig.8

Joseph Beuys

From the Eurasian Staff 1973

Screenprint

Tate P07598

© DACS 2019

In 1968, Beuys and musician Henning Christiansen performed the ritual action Eurasian Staff, 1967 at the Wide White Space Gallery in Antwerp, not far from where the city’s current Museum of Contemporary Art (M HKA) now stands. As the title indicates, it was first performed the previous year in Vienna, and the action involved a series of carefully orchestrated ritual movements, accompanied by an organ composition written and performed by Christiansen; it lasted 82 minutes, precisely the duration of Christiansen’s sound work. In Antwerp, the action was recorded on 16mm film, entitled Eurasienstab, Fluxorum organum opus 39 to distinguish the film as an artwork in its own right (fig.7).55 In the action, Beuys slowly erected four wooden columns wrapped in felt within the gallery space in a kind of ‘warming construction’, a task which required considerable strength; they were set up at an almost perpendicular angle of 82 degrees, mirroring the duration of the action. As he installed the beams, Beuys performed specific gestures such as placing margarine on the back of his knee before bending it (fig.8) or moulding it into the corners of the room to soften the right angles. He then wrote ‘Bildkopf – Bewegkopf<–>Der bewegte Isolator’ (‘Header – Moving Head<–>Moving Insulator’) in chalk across the floorboards of the space. Once the beams were up, Beuys picked up a heavy copper staff and walked with it around the light bulb hanging from the ceiling in the middle of the room, before finally leaning the staff against the beams. In conversation with one of the work’s curators, Anny De Decker, Jean-Philippe Antoine notes the congruence of the space, time and forming of angles presented within the action, concluding that Beuys’s effort lay in ‘How to produce a form by varying the angle of the joints … a form that can remain very chaotic, with the lumpy bits’.56 De Decker remembers that at one point during the action, Beuys stood for a very long time with his arm across his forehead. Afterwards she asked Beuys what he was referring to and recalls his referring to ‘something very far away, of a gazing into the horizon’.57 Reflecting on this gesture, she acknowledges a certain emphasis on the head, but also gives her personal impression that ‘his concentrated gaze seems to me to suggest … an act of looking from a very distant past into the future’.58

The academic Antony Hudek argues that there is a ‘timeline’ to Beuys’s engagement with Eurasia, beginning with an interest in Genghis Khan in his drawings of the 1950s and 1960s, and developing into ‘a certain geo-political transformation of this mythification of Trans-Siberia and the East. He seems to get closer to a real Europe, but one founded on an imaginary originary land.’59 Yet in many respects, it is the fact that Beuys’s new myth does not confine itself to the geopolitical and rather focuses on the spiritual elements of human perception and creativity that makes it of particular interest. Certainly, the M HKA’s claim that in this action Beuys was ‘symbolically reuniting the four winds of Eurasia, seeking to reconcile Asian spirituality with European rationality’ using the ‘Eurasian staff’ may raise Jonathan Harris’s concerns about simplistic dualisms.60 Yet there is a sense in which Beuys is teaching the audience an important lesson about materials, balance and human potential. The action demonstrates people’s power of forming and warming rigid forms up through movement, and their potential to both perceive substance and materials on a number of levels that go beyond their immediate use value and to think with the whole body, not just with the head. As with the different movements of the Siberian Symphony, there is also an impression – indicated by De Decker’s sense that the past, present and future were encompassed within the action – that Beuys was pointing to challenges yet to come.

Beuys’s Eurasia and contemporary debates

It could be argued that Beuys’s notion of Eurasia is far easier to understand and reflect upon now, in the context of an art world that is somewhat more globally inclusive, although of course the artist never envisaged that the ‘art world’ would be the work’s sole horizon. Certainly, its emphasis on a spiritual rather than a solely geo-political premise, remains radical. The M HKA’s 2017 exhibition of Beuys’s work Greetings from the Eurasian included key works, including the materials from Eurasian Staff which Beuys had performed in close proximity to the gallery. In dialogue with its subject, and the work of the American artist Jimmie Durham, the gallery decided to adopt Eurasia as a lens through which to frame its identity and focus. De Baere explains in the exhibition catalogue, ‘When M HKA started to call itself a Eurasian museum, it did so out of a sense of surprise at the obedient way in which the art world followed the geopolitical media image of the moment, and as an alternative perspective to be tried out, a possible antidote’.61 In the catalogue introduction, curator Nav Haq looks at Eurasia in the present in terms of its polarities and in the context of globalisation. He notes that Beuys’s ‘world view is to look incomprehensibly far beyond, and not to be isolationist. A trait we find very relevant in the crisis of today’s political climate, with rampant identitarian and nationalistic movements having emerged in many European nations and beyond.’62 While acknowledging critiques of Beuys that are concerned with idealisation and orientalism, he goes as far as proposing that Beuys ‘took on the role of the subaltern’ in the sense in which critical theory takes that term to refer to ‘the vast swathes outside of hegemonic power’.

Previously, I discussed Beuys’s interest in the nomad both in the ethnographic sense of the Tartars and semi-nomadic Mongol communities of Central Asia and their spiritual practices, and in relation to his reference to nomadic cultures in the development of an expanded notion of art. The term nomadism could also be used in reference to Beuys’s interest in Eurasia and the utopian spiritual concept of EURASIA in a more theoretical sense. Beuys’s interest in the nomadic emphasis on movement exemplifies a desire to work against constraining and debilitating divisions in order to release human creative potential. As such, the artist’s position strongly brings to mind the writings of philosopher Gilles Deleuze and radical psychotherapist and philosopher Félix Guattari in their essay ‘Nomadology: the War Machine’, first published in A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia.63 For Deleuze and Guattari a sedentary mode of living is fixed, and a nomadic mode of living is chaotic, but easy stereotyping should not be assumed in relation to this framework. A migrant, for example, may remain within a sedentary mode and somebody living in one location can still be itinerant. Certainly, in an ethnographic sense, the nomad does not seek a single fixed point of location, however Deleuze and Guattari use the analogy of the nomad to argue that it is countercultural tactics developed on the run – on the way to work, or in bars, for example – that enable people to militate against repression and move away from an established sedentary mode. Thus, the theory is not so much an engagement with nomadic cultures as a framework for understanding how to subvert rigid and repressive modes of governance.64

Significantly in relation to Beuys’s interest in movement and materials, this subversion occurs through movement; nomadology can be seen in an abstract way in the sense that it ‘maps an ontology of movement’.65 Furthermore, like Beuys, Deleuze and Guattari’s work is concerned with notions of materials. For them, ‘nomad’ or ’ambulant science’ differs from ‘royal science’ in its response to materials on the ground through approximation, where the nomad is engaged with ‘following the flow of matter’. In many respects, these descriptions of fixity, chaos and movement greatly resemble the two poles of Beuys’s sculptural theory and as a former soldier championing human freedom through movement, it is difficult not to see in the figure of Beuys a nomad in Deleuze and Guattari’s sense. At the same time, accounts of Beuys on the move, responding to chance and other people with interest and creativity, brings to mind ad hoc solutions ‘developed on the run’.66 Recalling the figure of the hare in the ‘Eurasian’ actions, this way of being clearly reflects and allows for a particular set of relations with other living beings which are also in movement and these certainly appear as ‘relations of becoming’.

However, the nomadism of Beuys’s position includes a genuine interest in nomadic traditions, coupled with an emphasis on spiritual warmth and an expanded notion of materials that it could be argued is missing in the philosophers’ rhetoric.67 The figure of the nomad is referred to by Beuys as a kind of essence, a means to work against ‘repression’ but also to stimulate people to seek balance and develop new, less rigid state forms. In this context, the Tartar story appears as a myth that does not teach about war, but about healing; for Beuys it relates to the potential of an expanded notion of materials and their creative use. Beuys’s nomadism, if you will, is a model that allows for a creative, historical process and significantly, where Deleuze and Guattari’s model focuses principally on geography and geopolitics, Beuys’s position involves a spiritual warmth element in terms of people’s felt encounters with materials, suggesting greater porosity between human beings and the wider environment. Hence the artist’s ‘warmth work’ appears as a force for countering static and entrenched positions, an element that was palpable in the artist’s work with people in Northern Ireland at the height of the Troubles, however naïve it may have seemed to many.68 All people are in process and movement, yet some may harbour thought forms that have become rigid and unyielding in ways that may be entirely understandable given historical and political contexts, to say nothing of lived experience of violence. However for Beuys, rigid thought forms bolster conservatism and block progressive change. The artist believed that thinking on both sides of a political divide could be warmed up and cooperation made possible through dialogue and movement.

Fig.9

Joseph Beuys

The Pack 1969

Das Rudel

Staatliche Museen Kassel, Neue Galerie

© DACS, 2019

In certain respects, the nomadism of Beuys’s work explains why the artist’s unconventional spiritual, geographical and conceptual positioning in relation to Eurasia may have escaped in-depth research until relatively recently. Until the 1990s, the art world in the West was so geographically fixed and largely centred on Europe and North America, occupying itself with particular notions of value. As an imaginative form for thinking about creating an existence beyond state capitalism in the East and private capitalism in the West, Beuys’s EURASIA proposition would have shifted the focus elsewhere. At the same time, the political and anthropological elements of Beuys’s work have often been viewed with suspicion and, at times, incomprehension. Yet the forceful substantive qualities of his practice demonstrate, rather than simply symbolise or illustrate, the material and spiritual forces sustaining living beings. These can be seen clearly in one of Beuys’s most famous works, The Pack (Das Rudel) 1969 (fig.9), which, in an animated way, shows all that a human being would need to exist in extreme circumstances, conveying something essential about people and their survival. This is notably through an evocation of dynamic movement away from industrial achievement, the VW van, towards an open horizon, drawing from other energy sources in order to survive.

Fig.10

Joseph Beuys

Scala Napoletana 1985

Wood, steel wire and lead

Tate AR00086

© DACS 2019

In a more contemporary, global context, the question remains as to whether Beuys’s – and to an extent Paik’s – vision of Eurasia has continued relevance today. We are, I would argue, left with a strong diagnostic quality in the work, which can assist us in perceiving where thinking is becoming dangerously hardened and entrenched, and provides us with expanded sculptural methods of warming the situation up through focused thinking, feeling and willing. An emphasis on balance runs through Beuys’s work and Scala Napoletana 1985 (fig.10), created near to the end of the artist’s life, expresses this with elegance and power. Beuys constantly balanced energy qualities – conductors and insulators, chemical compounds – stimulating interior processes in people that feel, at times, homeopathic, in that as well as energy, the work often feels as though it contains a tiny element of pain that triggers a healing process. Beuys’s work allows us to see where things are becoming crystalline, rigid and cold, calling us to respond with a counteracting and balancing warmth. Further, because the artist’s methodology confronts an extremist perversion of knowledges and symbols by reworking such narratives in healing ways, it indicates where these are being used in a manner that moves them away from their wisdom dimension towards the cold pole.

Drawing from Beuys’s sculptural model, it is not hard to perceive that in the West, on the side of private capitalism, things have reached a very cold state. Brexit is a particularly alarming example of growing hardened and extremist nationalist discourses on the rise all over Europe. Beuys was deeply concerned that carving up Eurasia enacted harmful divisions that played out at the geographical, psychological and thus spiritual level, forcing people into a distorted relationship with their environment and one another. At the same time, right-wing populism is also rearing its ugly head in the USA and in both Europe and the USA, living in the shadow of the peaks and troughs of the money markets reduces many to precarious lives devoid of dignity. In Russia, Putin’s Eurasia is a cold form that looks increasingly like neo-fascism, espousing the expansion of intolerance as much as territory. In China, under a form of state capitalism, the super-wealthy entrepreneur lives cheek by jowl with the poverty-stricken, if gainfully employed, streetsweeper. Freedom is limited. The Chinese word for harmony, He Xie in Western characters, is invoked by the state to ensure that people work for the common good.69 Ostensibly laudable, this has come to legitimise ever more dictatorial edicts enforced over the will of the people and recent revelations of the internment of Muslims in vast camps have done little to assuage international anxiety. In such circumstances, freedom – and most visibly perhaps, that of the professional artist – is circumscribed. He Xie is also a homonym for the word for ‘river crab’; after the Chinese State commissioned his new studios, then ordered and carried out their destruction, contemporary artist Ai Weiwei produced a sculpture of a pile of porcelain crabs (He Xie 2010, private collection), commenting on the state’s use of the term to repress creativity and freedom. In Beuysian terms, we might say that the state has been turned into a hardened form as rigid as a crab’s back, but even under its cruel shell Beuys’s methodology indicates that there is soft substance which, with ‘warmth work’, could be brought to the surface.

In conclusion, the importance of bridging history and crossing borders in order to initiate the development of new social forms that would secure people’s future dignity is precisely what made Beuys look to the periphery of Europe and beyond it to Eurasia. The artist’s interest in Eurasia and his development of EURASIA as a utopian concept was not distinct from his interest in Europe, but rather a way of seeking a state of wholeness for Europe as part of a larger and higher spiritual, rather than purely political, state form. It was not an extremist preoccupation with ever widening territories, but a desire to dialogue with and integrate different concepts of knowing and being; an artistic framework of creative activity between sculptural poles encompassing people’s power to act with love in connection with their interior and exterior environments, as a matter of urgency for both.70 It was not an attempt to force agreement, but rather to stimulate ongoing dialogue that might lead to cooperation. Today, the utopian concept EURASIA may itself require re-envisioning in relation to contemporary contexts, but it surely constitutes an extremely valuable place to start to look for ways to confront contemporary challenges actively with courage, creativity and compassion.