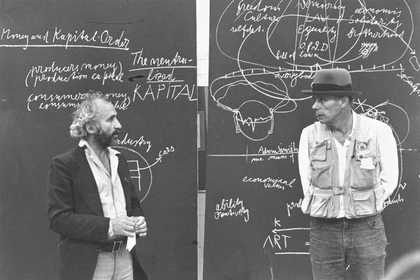

Fig.1

Richard Demarco and Joseph Beuys in front of blackboards from Beuys’s action Art = Kapital/Jimmy Boyle Days during the ‘Alternative Policies and the Work of the Free International University’ event at the Richard Demarco Gallery, Edinburgh, 25 August – 6 September 1980, part of Edinburgh Arts 1980

Demarco Digital Archive

Christian Weikop: During Strategy: Get Arts, did the younger artists acknowledge Beuys (fig.1) as the ‘leader’ of the Düsseldorf pack? Although he wasn’t involved with your 1970 exhibition, when I interviewed Anselm Kiefer in 2013 for the Royal Academy, he told me that the most important influence on him in the late 1960s and early 1970s was undoubtedly Joseph Beuys. He said that there was no question he was one of the most important artists of the twentieth century.

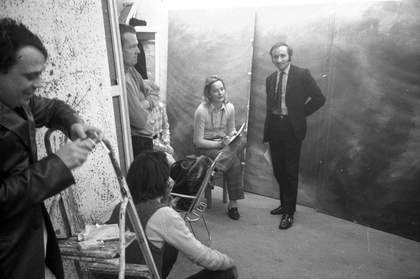

Fig.2

Günther Uecker (left) and Richard Demarco (standing, centre right) at a meeting in the studio of Gerhard Richter in Düsseldorf on 29 January 1970, during preparations for the exhibition Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art

Demarco Digital Archive

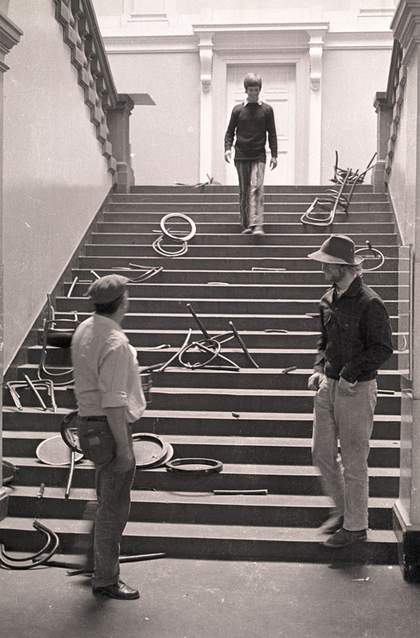

Fig.3

Detail of Stefan Wewerka’s installation for Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art

Demarco Digital Archive

Photo © George Oliver

Richard Demarco: Oh really! It is very interesting that Kiefer thinks that about Beuys. Kiefer is regarded so highly. By the way, it was actually in Gerhard Richter’s studio, Richter being a great friend of Günther Uecker, that the concept of Strategy: Get Arts was developed. I have a photograph where I am talking about my plan for this exhibition at the Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) and they are listening attentively (fig.2). It is tragic that they whitewashed every single trace of Strategy: Get Arts, including Blinky Palermo’s frieze. The decision to whitewash by the powers that be, including William Gillies, who had been the Principal of ECA, was made because they thought that this pristine ‘temple of truth’ had been invaded by hooligans, people who were not artists. They simply didn’t understand an artist like Stefan Wewerka, whose broken chairs on the main staircase was actually a homage to Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (fig.3).

Christian Weikop: That’s interesting. When looking at archive photographs, I didn’t make that connection to Eisenstein myself, although I can quite see the association to Battleship Potemkin now you mention it. Before we talk about Strategy: Get Arts though, could you say something about your career before this exhibition?

Fig.4

Horia Bernea, Joseph Beuys, Henning Christiansen, and Johannes Stuttgen at the exhibition New Directions at the Richard Demarco Gallery, 8 Melville Crescent, Edinburgh

Demarco Digital Archive

Richard Demarco: At Edinburgh College of Art, I began my career organising exhibitions. I ran the student exhibitions around 1951–3 and organised the students’ journeys into the Scottish landscape. On one occasion, we travelled to Loch Lomond and I saw the road to Meikle Seggie, and the students reacted to that thing that was like a gift, that which makes Scotland a superior place to study, in my mind at least, because of the incredible landscape not far from Edinburgh. After my education at ECA, I was an infantry soldier in Berwick (my military service). I then became a sergeant instructor in the Royal Army Education Corp in Oxfordshire, and when I came out of the army I became the Art Master of the Duns Scotus Academy, which had only been open a few years. I had no doubt that teaching art was a great way of educating human beings. This was 1957 and I taught there for ten years. But in 1963 the Traverse Theatre was founded by me along with Jim Haynes. I also met Ian Hamilton Finlay at the Traverse. His wife Sue became one of the first members of my voluntary staff. The Traverse Theatre evolved from the Paperback Bookshop, which was a tiny space next to the Edinburgh Student Union. The maximum number of any audience was twelve. And of course in 1966, the Richard Demarco Gallery was founded at 8 Melville Crescent in Edinburgh’s New Town (fig.4).

Christian Weikop: It seems that alongside your role as a gallery director, art education and teaching has been very important to you over the years.

Richard Demarco: Have you read the essay I wrote for Pages magazine?1 In that interview I said, ‘I am not a gallery director’, that means a shopkeeper, selling art. I am essentially a teacher like Joseph Beuys. Strategy: Get Arts had much to do with art education. It was presented in an art college rather than in a gallery. I asked Beuys, ‘What is the nature of your art, Joseph?’ He said to me, ‘My art is my teaching.’ So anyone involved in the concept of art teaching is someone close to what I believe in.

Christian Weikop: What about the early days of the Edinburgh Festival?

Richard Demarco: The Edinburgh Festival was the greatest learning space in the world. I was meeting people like Thornton Wilder, Richard Burton, Claire Bloom, Audrey Hepburn and T.S. Eliot. In the early fifties, I was a receptionist at Edinburgh’s Caledonian Hotel and greeting extraordinary people like Eliot and Sir Alexander Fleming. In the late 1950s, I bought a top floor flat for a few hundred pounds in Frederick St, right in the centre of Edinburgh and looking out to the Castle. This became the location for soirees, attended by local and visiting artists, writers, actors, musicians, students, and many others with an interest in the arts.

Christian Weikop: What were the circumstances by which you first came across Joseph Beuys?

Fig.5

Edgar Negret at the 1968 Venice Biennale

Demarco Digital Archive

Richard Demarco: This was an interesting chain of events stemming from the playwright Paul Foster’s involvement in Ellen Stewart’s ’Theatre la MaMa’, and a programme from ‘la MaMa’ travelled to Edinburgh in time for the 1966 Edinburgh Fringe. It was Foster who suggested that the Demarco Gallery present an exhibition of sculpture by his friend Edgar Negret, then Columbia’s leading artist (fig.5). This led to the Demarco Gallery representing Negret at the 1968 Venice Biennale! So I travelled with Negret to Venice and he only went and won the Sculpture Prize! That means we are told to travel to Amsterdam with the Director of the Stedelijk Museum, because Negret would be given a show there as part of the prize. And someone said, ‘Oh, and by the way we will stop off at Kassel on our journey to see the Documenta’. It was one of those few years that the Documenta coincided with the Venice Biennale, which does not happen so often. We did a quick tour of the Documenta and every major artist was there and eventually we arrived at the main building. They were anxious to get back on the train to Holland, but I wanted to stay and witness something that as far as I was concerned was completely and utterly overwhelming. I was watching this strange figure beginning to re-adjust what I could see were the finishing touches to a piece of sculpture. But it looked like he might have been a scientist, as there were what could have been scientific objects on tables – glass objects, and felt.

Fig.6

Joseph Beuys

Room Sculpture (Raumplastik) 1968 at Documenta 4, 1968

© Robert Lebeck Archive

Christian Weikop: This was Beuys’s Raumplastik (fig.6)?

Richard Demarco: Yes, I stood there and it was one of these great moments when you realise you know nothing. Everything you have ever experienced has come to a point where you are completely dependent on something happening inside your soul and not your brain.

Christian Weikop: Were you already aware of Beuys’s artistic reputation at that point?

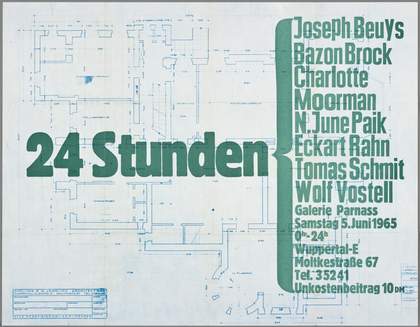

Fig.7

Joseph Beuys

24 Stunden 1965

Tate AR01036

© DACS 2019

Richard Demarco: Yes, from a small book that I had been given called 24 Stunden, which documented Beuys taking part in a ‘happening’, a midnight-to-midnight performance in Wuppertal in 1965, along with artists such as Wolf Vostell, Nam June Paik and such like (fig.7). It was a one-off and that is where I first saw a photograph of Beuys in action. I didn’t realise that what I was looking at was a piece of ‘social sculpture’.

Christian Weikop: At Documenta, did you at any point exchange words with him?

Richard Demarco: No, he was at a distance from me and I was completely transfixed. I had observed truth and beauty. I had never seen anything like it. Can I tell you, it was like being on your honeymoon with your new bride on your arm. During those first moments when I was watching Beuys they were urging me to get out in order to catch a train. I didn’t have time to go up to him as I wanted to. I left Kassel with a heavy heart.

Christian Weikop: Was this before or after the Canada 101 show at ECA?

Richard Demarco: It was the same year – 1968. This was an annus mirabilis for me because it was also the year that the Polish Ministry of Culture invited me to Poland. I went to Łódź and discovered the Muzeum Sztuki, which is as old as MoMA in New York. Łódź was also onetime capital of the world’s textile industry, once a city of German and Russian as well as Polish inhabitants, with a large Jewish population. I became friends with the Director of Muzeum Sztuki, Ryszard Stanisławski. I went to Wrocław and met Jerzy Grotowski. I also went to Warsaw and was invited to go to Romania. I flew from Warsaw to Bucharest. I was flying to the world of Constantin Brancusi and Tristan Tzara.

Christian Weikop: To the world of the Romanian Dadaists of Cabaret Voltaire!

Richard Demarco: Exactly right!

Christian Weikop: Didn’t you also show Günther Uecker around this time?

Fig.8

Günther Uecker

White Field 1964

Tate T00684

© Günther Uecker

Richard Demarco: In 1967, I went to the first ROSC exhibition in Dublin, which is where I met John Latham, the English artist who was represented by his burnt book sculptures. I regard Latham as the British equivalent of Beuys. I also encountered Uecker, who was the spirit of Gruppe Zero. He introduced me to Heinz Mack and others. Uecker became my friend in Dublin and I spent a lot of time with him. He said, ‘I am so happy to be here because this is where my sister’s husband studied’. And I said, ‘Oh really, who is her husband?’ Uecker told me, ‘Yves Klein’. Well, Klein was my hero! My whole plan was to bring him to the Edinburgh Festival because 1967 was the year that I was appointed by Peter Diamand to be the Festival Director of Contemporary Visual Art Exhibitions. Incidentally, do you know why Uecker used nails in his artworks? (fig.8)

Christian Weikop: I should, but I am afraid I don’t.

Richard Demarco: Well, during the war when the Russians were advancing they were pillaging and raping everybody in sight. And the poor German population, especially the womenfolk, were in complete fear for their lives. The young Uecker, who is exactly my age, boarded up every window and every door of their house, hammering in nails so the house was impregnable, and he saved his mother and his sister from being raped. One of the most important works in Strategy: Get Arts was the sound of Uecker’s door opening and closing, a piece which was a bit like Duchamp’s door in the Philadelphia Museum of Art [Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas… (Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau, 2° le gaz d’éclairage…) 1946–66]. Uecker’s work stemmed from this wartime experience even though he was part of Gruppe Zero, which was all about new beginnings.

Christian Weikop: Did Uecker speak to you about Beuys when you were in Dublin?

Richard Demarco: Yes, well he spoke to me about the fact that I should go to Düsseldorf. He said that was where all the key artists were now gathering. I was already thinking about going to see him. He told me all about Gruppe Zero. I should explain that I don’t separate Uecker from Beuys. He was a good friend of Beuys. It was Uecker’s energy and contacts with all the other artists that was important. Uecker was a refugee like Gerhard Richter. He was an East German. He had to cross the border and start a new life.

Christian Weikop: He was a ‘Grenzgänger’ then. That’s the German term for ‘border crosser’.

Richard Demarco: Is it? Thank you for telling me. I must remember that. So, Uecker said you should take very seriously what is happening in Düsseldorf and that is when it penetrated my consciousness. I had been to Europe in the year of the Brussels EXPO [1958] and that gave me the chance to visit Essen and various other German cities that were still in a state of ruination.

Christian Weikop: How old were you when the Second World War broke out?

Richard Demarco: I must tell you that meeting Beuys took me back to the year when the war began because I was nearly the first ever victim of the Second World War, a child casualty. I just escaped from being shot; the bullets were only two or three inches from my legs. But it was friendly fire. The bullets were from a Spitfire, the first time a Spitfire had been used in conflict, finally causing a German bomber to be in its death throes. It was the first German aircraft to be brought down over Britain since the First World War. I was watching it on the beach of Portobello [a coastal suburb of Edinburgh] in the first few days of the war. I became transfixed by the two pilots a few minutes before they died. I could see their faces through the cockpit. At first I waved to them, unafraid, unaware that behind them was this Spitfire, but I then saw the engine on fire. Later, my father showed me the Scotsman with photographs of the two Luftwaffe pilots, who were very young, one aged seventeen and the other nineteen. They were regarded as heroes by the people of Edinburgh. Thousands of people lined the streets from St. Philip’s Church and they were buried in Milton Road Cemetery.

Christian Weikop: And you were a young boy around ten years old?

Richard Demarco: I was nine. I asked my mother whether I could go to the funeral. She agreed. There is a British Movietone newsreel which shows the German coffins draped in swastikas, outside the church. They were given full military honours. That empathy with the mothers of the German airmen, the fact that they were just boys, that also expressed my own feelings about war. I was untouched by the propaganda.

Christian Weikop: Your witnessing of this air conflict, do you make a connection between this dramatic event and what happened to Beuys – getting shot down in his bomber?

Richard Demarco: Of course, he was about the same age as those pilots.

The Italians joined the Axis alliance in 1940. When that happened being an Italian was not a good idea. The artist Eduardo Paolozzi, who was interned, lost his father, grandfather and uncle, when the ship transporting them to Canada was sunk by a German U-boat. I was the victim of a lot of abuse. The Italian population suffered grievously in Scotland. I was attacked in the public baths. I could not walk along the promenades of Portobello because stones would be thrown at me. I got used to being defined as a ‘wop’. I realised I wasn’t Scottish or British, but something deep inside me told me I was European.

Christian Weikop: What was Paolozzi’s response to Strategy: Get Arts at ECA?

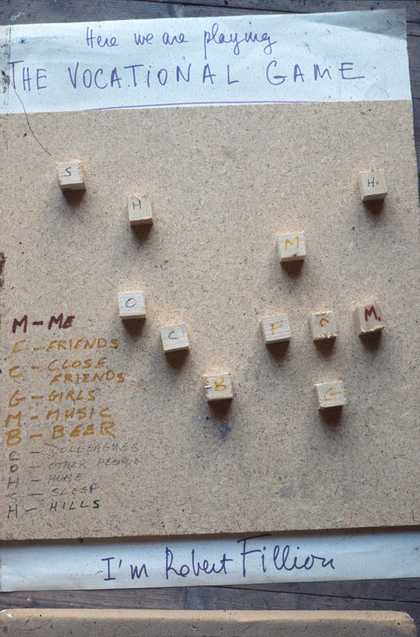

Fig.9

Robert Filliou

The Vocational Game 1970

Demarco Digital Archive

© 2019 Estate of Robert Filliou

Richard Demarco: He had been working in Germany, so he should have known, but I think it was all too much for him. It was too outrageous for him. He was into the whole business of making sculptures. And his reasons for making sculptures were rather different to those of these artists. Robert Filliou created his Vocational Game, an art game, his contribution to Strategy: Get Arts, where you were invited to create an art game out of simple cube-shaped pieces of wood on a strawboard base (fig.9). Paolozzi refused to play it when he came in.

Paolozzi is very important to me because I went to school just after he left Holy Cross and my art teacher said, ‘You must sit at that desk. That is where a boy who has just left our school sat, who like you, is an Italian Scot’. She was a Jean Brodie type teacher in love with the Italian Renaissance and she liked the idea that there were Italian students. Her name was Theresa Clarke. And she gave me Paolozzi’s notebook, full of his artworks. And I keep thinking what on earth happened to this wonderful notebook full of his schoolboy drawings? I am now on the committee that awards the Paolozzi prize to schoolchildren.

Fig.10

Exhibition visitors with some of the panels of Joseph Beuys’s Arena in Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art, 1970

Demarco Digital Archive

Christian Weikop: Could you say something about Beuys’s Arena (fig.10), which was shown at Strategy: Get Arts?

Richard Demarco: When I presented Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony at ECA, I also had to acknowledge the work that Beuys had done before, so we used the big life drawing room.

Christian Weikop: Is this where you also drew Sean Connery as a life model?

Richard Demarco: Yes, and it was where I shared my sandwiches with Connery!

That room was special to me. It was where I was educated. Anyway, when we were thinking about installing Arena, I said to Beuys, ‘I don’t have any money for frames’. He said, ‘It doesn’t matter, just put glass on each image, just put in on the floor or lean it against a wall.’

I don’t believe any great artist makes a number of different artworks. I think Rembrandt only made one painting, Shakespeare only wrote one play, and you have to take on board all the plays to get the full story. You’ll also find this with Van Gogh. Every painting has the same signature, the same handwriting. It is the same if you are listening to Mozart. You can play any Mozartian piece for two seconds and you will say, ‘Oh, that must be Mozart’. I believe Beuys only made one work and he underlined that fact by saying, ‘If you look at all these images [Arena] this is what I have done up to now’. I thought, ‘this is the work of a great teacher’. Then one of his students, Johannes Stüttgen, reminded me that he was beholden to many other artists. On the walls of the life room were pieces of paper, and on the first piece of paper was written ‘Where are the souls of?’. On the second piece of paper were the names of the artists who were being taken seriously into account by Beuys. Naturally there was the name Malevich, summing up the Russian avant-garde, Van Gogh, Fra Anglelico, Masaccio, and God knows how many others. I was surprised that some of the other names were more from the history of ideas, the history of civilisation. I realised this was a kind of requiem. And when Beuys was asked whether he wanted the floor of this life room to be cleaned (it was bespattered with paint), he replied, ‘No, no leave it untouched. These marks are evidence of all the human souls who have endeavoured to make art’.

Christian Weikop: He didn’t want evidence of the artistic working process to be effaced?

Richard Demarco: That’s right. He didn’t want the room to be cleaned even though it had become a temporary exhibition space. He also wanted the sinks and the corners of the room to be regarded as very special. He said, ‘The corner of a room is where there is an intensity of energy. That is where you can feel the intensity of the passing of time’.

Christian Weikop: Didn’t Malevich say something similar?

Richard Demarco: He did. Malevich was coming from the world of the icon. He was an icon maker. The final icon is the black square, which is where the monk ends up contemplating timelessness, or a space beyond the limitations of time. I also cannot separate my memories of Beuys from my memories of Henning Christiansen.

Christian Weikop: They had a close partnership or friendship, similar to yourself and Beuys?

Richard Demarco: Oh yes, incredible. And in 1995, twenty-five years after Beuys made the Edinburgh College of Art the one space in the English-speaking world to be blessed by his presence [in 1970], and with him these other great artists, Christiansen came back. He was tuning the piano and playing around with the sound of Scottish folk songs, like ‘O ye’ll tak’ the high road, and I’ll tak’ the low road, And I’ll be in Scotland a’fore ye’, or the traditional song, ‘You've never smelled the tangle o’ the Isles’. That is the smell of the seaweed as you head towards a great expanse of nothingness. He and Beuys were taking the road to the Isles seriously. Beuys needed Christiansen. I have never forgotten anything that happened in those spaces at ECA. It was the art lesson I had waited for all my life.

Christian Weikop: Talking of the road to the Isles, what connection did Beuys want to make with Mendelssohn when working with Christiansen on Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony?

Richard Demarco: Beuys knew the Hebrides Overture, which is the sound of the Atlantic inside the cave of Fingal. But he said to me, ‘It is too Romantic. It is not the right sound to represent the totality of Scotland’. So it was a requiem, taking into account all the artists who had gone before, especially those who remain unknown.

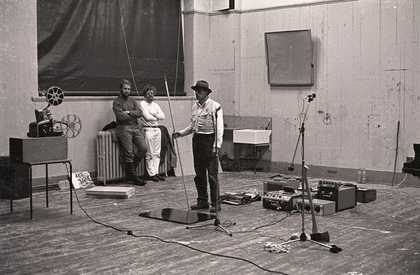

Fig.11

Performance of Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony 1970 by Joseph Beuys and Henning Christiansen in Strategy: Get Arts at the Edinburgh College of Art

Demarco Digital Archive

Photo © George Oliver

For Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony Beuys stood over the tomb of the unknown artist, represented by the blackboard. Beuys asked me whether he should use one blackboard or many, but like an idiot I said only one (fig.11). Nevertheless, he made these wonderful chalk drawings. I didn’t make that mistake the next time he came to Edinburgh! I realised that the blackboard signified his role as a teacher. And he used also a stick and various instruments in that room. I realised the whole space would be transmogrified.

Christian Weikop: That seems like a very spiritual metaphor.

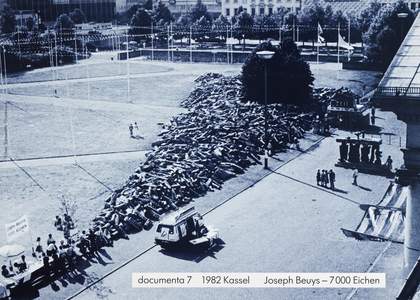

Fig.12

Joseph Beuys

7000 Oak Trees 1982

Tate AR00745

© DACS 2019

Richard Demarco: One of the scholars I invited to Edinburgh in 1989 for a Demarco Gallery symposium on Beuys’s Manresa was a friend of Beuys called Friedhelm Mennekes, who wrote a book saying that the core of Beuys’s thinking was based on Christian concepts, which have caused us to believe in the dignity of man, in democracy, especially through the Magna Carta and much later the decrees of the United Nations. But for some reason we still believe that the world will move forward when all the richest bankers on the planet meet in Davos! We do not believe that anything will come out of the next Documenta! Except that with each day that passes there will be the flowering of the 7000 Oaks and that is unstoppable (fig.12).

Christian Weikop: When and how did 7000 Oaks come into being?

Fig.13

Cover of Richard Demarco, The Road to Meikle Seggie, Edinburgh 1978

Demarco Digital Archive

Richard Demarco: In Scotland, on the road to Meikle Seggie (fig.13), when Beuys and I looked at a hillside where there was a plantation of fast-growing Norwegian firs. They made that hillside look as if it was anywhere but Scotland. Beuys then said, we should not be planting these trees, we should be planting the kind of tree that grows in the ancient woodlands of Scotland. That was on the slopes of the hills around Loch Awe and the first piece that he made was the Loch Awe piece, which he gave to me.

Christian Weikop: This was May 1970?

Richard Demarco: Yes, and the first piece he made was not at the Edinburgh College of Art, it was made on the road to Meikle Seggie.

Christian Weikop: That’s fascinating. So you think that the concept of 7000 Oaks was already forming from his experience of what you were giving him in Scotland?

Fig.14

Joseph Beuys at Loch Awe, Scotland, 8 May 1970

Demarco Digital Archive

Richard Demarco: Absolutely. And what is more, if you look at any image of Beuys on his visits here in 1970, you can see that he was trying to deal with the Scottish bog land, with the moorland, with the oldest surfaces of the planet, with the Arctic tundra, with the spaces before the arable (fig.14).

Christian Weikop: Do you think the idea of a ‘Celtic’ landscape and geography and ‘Celtic myth’ informed Beuys’s work as much as the cultural and mythic dimension of German forests?

Richard Demarco: Beuys was fascinated by the ancient world of Druids. They created the sacred sites to convey their understanding of the importance of nature. And there were two key images in this Druid world. One image was the oak tree, the second image was the basaltic stone. Now the reason Beuys was so interested in the basaltic stone was because it was the result of a volcanic eruption, the convulsive nature of the earth when it was forming itself, when for example the landmass of Europe was connected to the landmass of North America, when for example the British Isles was forming itself. He said that any artwork should contain all time rather than just a bit of time. 7000 Oaks is linked to the lifespan of the oak tree. From a sapling they go to maturity and die over a period of 700 years. That 700 is related to 70 years in Shakespearian and Biblical terms, which is the lifespan of a human being, a span of seven stages. The oak grows in seven stages just like a human being. But time began in the formation of rocks. The magical nature of basalt was evidenced in the mythological world of the Celts, which led them to the veneration of Fingal. His world is to be found in his cave on the Hebridean island of Staffa. But if you look as a geologist or a geographer would at Fingal’s Cave, you will see that it is one end of an underwater link, a strata of stone which leads you on to the other side of the Irish Sea, to the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland. It is part of the same geological formation. Beuys visited the Giant’s Causeway. The basalt columns there inspired him to use basalt as markers for the 7000 Oaks in Kassel. If you place an oak tree in the ground you will have a defined time space of 700 years, and looking at it, the human being will think seriously about the passing of time, from birth to death and rebirth. If you add a basaltic marker besides it, you have a marker of all time, going right the way back to the Big Bang.

This force of nature is not fanciful, it is a fact. Beuys was very interested that he came from a part of Germany that was a Celtic enclave. That part of Germany is influenced by the Celtic monks (hence Mönchengladbach). I would say that Beuys had to come to Scotland, there was no other choice. He had to come to Scotland to take on board the extension of the Celtic world that he had lived with from his childhood.

Christian Weikop: Can I also ask, do you think that your Catholic upbringing in Scotland and Beuys’s upbringing in this ‘Celtic-Catholic’ enclave of Kleve, and the fact that you were both in a sense from marginalised circles in your respective countries, living in predominantly Protestant areas, meant that you had some kind of natural sympathy?

Richard Demarco: That is a very important question. That was at the heart of our way of looking at the world. We often talked about ritual and the sacramental life. There are seven sacraments, there are seven deadly sins, there are seven cardinal virtues, there are seven days of the week. Think of a great creator like St Columba, who was just like St Ignatius. Beuys responded to Columba and Ignatius as two soldiers who had been involved in warfare, but who were able to rethink their lives. I said to him that you cannot separate the pagan world, where nature is king, where the oak tree is king, from the message of Christianity. And Beuys knew this very well. The prime example of a Celt is Columba. The followers of Columba were missionaries who went spreading the truth that they embodied through every land in Europe, up the rivers to convert the pagan world. We forget the origins of Christianity in the turmoil of the Reformation. We have to understand that Columba had to leave the place of the Druids, the place of the oaks, but when he did, he landed on an island inhabited by Druids, namely Iona. He explained to them it was not enough to worship an oak tree, or the sun; they had to take on board the message that came through the Roman Empire. Beuys was interested in the cross of St Martin of Tour, a Roman legionary who was martyred because he followed Christ and not the pagan Gods of the Romans. The reason why Beuys wanted to take seriously Celtic mythology was that he had to take on board the sea girt world where the landmass of Europe ends and the great power of the Atlantic Ocean begins. This brings a kind of light, a kind of space that breeds poets and the bardic tradition. These early Celtic monks were the ones who had the responsibility of creating the libraries and the places of study. When I think of the Book of Kells, I think it is the greatest work of art to ever come out of Scotland.

Christian Weikop: To digress, although still thinking of great Scottish art, you mentioned Ian Hamilton Finlay earlier. Did Beuys and Finlay ever meet?

Richard Demarco: I really wanted them to meet in 1980, but this is when I became involved in a nightmarish scenario with the Scottish Arts Council because that was the year when Beuys decided to cut short his seven days at the Edinburgh Festival in protest against the Scottish prison system.

Christian Weikop: That was the case of Jimmy Boyle wasn’t it?

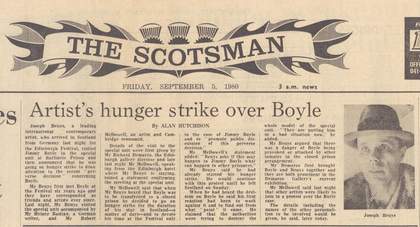

Fig.15

Alan Hutchison, ‘Artist’s Hunger Strike over Boyle’, Scotsman, 5 September 1980

Demarco Digital Archive

Richard Demarco: Yes, Beuys went on hunger strike and he signed a document accusing the Secretary of State for the poor condition of the prisons (fig.15). He pointed out how mad it was for a person such as Jimmy Boyle, who had been working for seven years with potentially lethal implements such as knives and chisels, to be put back into the normal prison system in handcuffs. He said that when you become an artist, you recognise yourself as a creative human being and therefore you confer freedom upon yourself. It was a beautiful statement, but of course it caused utter confusion in the minds of the authorities. And I was condemned as bringing dishonour to the meaning of art! Can you imagine? I was an outcast.

Christian Weikop: What about Beuys and his connections to the Polish avant-garde? What year and how did Beuys meet Tadeusz Kantor?

Richard Demarco: Well, I was trying to find ways to continue the original idea of the Edinburgh Festival. The festival began with the idea that the language of art was the language of healing. This was expressed in the foreword to the official programme for the first festival in 1947, namely that the festival was to provide ‘a platform for the flowering of the human spirit’ in the wake of the Second World War. It was in no way supposed to be a commercial venture. I knew that it was a healing balm. It was part of the process of rebuilding Europe, but also ridding Europe of the pain and the suffering and the scars. Beuys’s art was all about being able to ‘show your wounds’, not being afraid to expose weaknesses. And he personified the soul of Germany. Who are the most powerful users of the language of healing, which is the language of art? Beuys and Kantor. I invited both of them to be on my faculty for Edinburgh Arts 73, which although it started in 1972, was really the classic Edinburgh Arts when it really took off. Edinburgh Arts was the Scottish version of Black Mountain College in North Carolina. It signalled the transformation of the Demarco Gallery into a place of education and was an extension of the art studios of both ECA and the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf. I have to admit that Edinburgh Arts could not have happened without Edinburgh University. It gave academic credits to American students through the School of Scottish Studies and School of Extramural Studies.

Fig.16

Joseph Beuys emerging from the Forrest Hill Poorhouse, Edinburgh, at the time of the ‘Black and White Oil Conference’, Edinburgh Arts 1974. Cricot 2 posters on the door from 1973.

Demarco Digital Archive

It was important to have Kantor and Beuys work together; a symbol of the fact that Polish and German artists are at the very heart of Europe. So the moment came. Kantor had got himself worked up because someone suggested that they paint the flagstones on the floor of the Edinburgh Poorhouse with grey paint, and Kantor had gone berserk that some idiot had attempted to cover the surface of the historical reality of the building. The Poorhouse was bedlam and within its walls died thousands of people. It was in 1973 that Kantor and [the theatre company] Cricot 2 did a big performance there (fig.16). It was right and fitting that they should be doing this in a place of death and dejection and madness. What a risk I took, but it paid off. The University of Edinburgh did not understand what was going on, but they allowed me to do it.

Fig.17

Joseph Beuys at Tadeusz Kantor’s production of Lovelies and Dowdies, Forrest Hill Poorhouse, Edinburgh Arts 1973

Demarco Digital Archive

Sandy Nairne, who was my assistant, and who much later became the Director of the National Portrait Gallery, brought Kantor to my flat in Frederick Street. So when Kantor came in he was still angry about the flagstones. As he walked in with Sandy, the door opened and there I was with Beuys. I said ‘Ah, Tadeusz, I want you to meet a friend of mine’. Kantor’s surprise and astonishment that one of his heroes was in the room was manifest, and suddenly all anger dissipated, and he was quite overwhelmed. The direct result of that meeting was that Beuys agreed to be part of a performance of Lovelies and Dowdies at the Edinburgh Poorhouse in the late summer of 1973 (fig.17). So, Beuys and Kantor began their friendship in my living room in Frederick Street and it continued because Beuys agreed to be part of Kantor’s performance. It was a perfect moment for Beuys and Kantor to meet. In fact there should be a plaque up on the wall stating, ‘This is where two great artists of the twentieth century met each other, personifying the spirt of Poland and Germany, in a state of reconciliation’.

Christian Weikop: Clearly the 1970s was quite an extraordinary period in your career.

Richard Demarco: Yes, but please understand that I never really presented Beuys, Kantor, Uecker, and others, I collaborated with them. I said to them, I want you to come on a journey. I want you to experience something, and art will arise from the coming together of our experiences, taking in the whole history of the Celtic mindset, taking in the Celtic consciousness. The Greco-Roman consciousness finally leads to the Enlightenment, which I regard as the ‘Endarkenment’. It is the beginning of the end. It is the beginning of the formation of a system of education which denigrates the use of art language and replaces it with the most dehumanising language, which is the language of rational thought. The whole system has to be re-thought. Not many people agree with me, but the one language that can provide a future for education on any level, primary, secondary, or tertiary, is art. And this is what brings the theories of Beuys into play. That is what he means when he says everybody has to be creative. The answer is not to create a monster, which is an industrialised art world that is totally dependent on tourism and leisure and on the dehumanising of the work space. We are now completely dependent on turning everything into a festival, but not for the right reasons.

Two weeks before Beuys died [23 January 1986], he phoned me up. I knew he was in a very bad way, but I was heartened by the sound of his voice. He reassured me that he was going to come to Scotland again. He said ‘Douglas Hall [the first Keeper of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art] thinks I am going to put on some kind of retrospective. I am not interested in retrospectives. You promised to take me to the grave of Adam Smith’. I said, ‘yes I want you to see the grave, it is half way down the Royal Mile’. I will never forget the last time I heard his voice on the telephone. He said ‘Richard, don’t worry I am coming back. I will be with you soon’. Then he said, ‘Richard I have to go now’. I said, ‘at least we are going to meet’. The last words he spoke to me were, and I have to take this as the overwhelming message: ‘Richard, I love you’. And my last words to him were, ‘Joseph, I love you’. I think art is the only language you can use to define truth and beauty. I think it is the one language that we should be grateful for as human beings. I think it enables us to speak beyond the limitations of our lifetime.

Edited transcript by Christian Weikop.