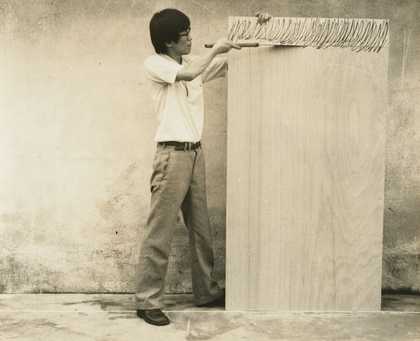

Consider the black-and-white photographs of Body Drawing 76-01, a performance conceived and executed in 1976 by Lee Kun-yong, one of the foremost early champions of performance art in Korea. The work took place on the rooftop of the Seoul studio belonging to his friend Sung Neung-kyung. Taken by Sung at Lee’s direction, the photographs reveal the order in which the performance took place. Against a nondescript background a plywood panel stands upright, steadied by two hands reaching over its top edge (fig.1). The hand at the very left reaches over the edge and appears to be drawing on the panel with a permanent black marker. Diagonally orientated, the drawn lines vary in length, the result of the man behind the panel not being able to see his handiwork from the front. Another photograph reveals the body to which the mysterious hands belong, now attached to arms that wield a long saw (fig.2). Standing next to the piece of thin plywood roughly the same height as himself, a bespectacled Asian man in his thirties saws the marked portion, calling attention not only to the material nature of the plywood, but also to the manual labour involved in creating the work. This process of marking and then sawing the plywood continued until the panel had been cut into five separate parts. These marked portions were then placed on the ground and progressively stacked until the original plywood board was reconstructed as an accumulation of marked bands with what was once the uppermost band at the bottom (figs.3–7).

The mid-1970s was a profoundly difficult time for artists in Korea and indeed the general population. Body Drawing 76-01 was undertaken almost four years after South Korean president Park Chung-hee declared martial law in the name of protecting the South Korean citizenry from the communist threat embodied by North Korea’s very existence. Euphemistically framed as a ‘restoration’, or in Korean ‘Yushin’, this period of martial law lasted almost seven years from October 1972 to 26 October 1979, when Park was assassinated. In many respects Yushin was only a symbolic benchmark, the culmination of the steady expansion of government power and the commensurate diminution of alternative forms of authority that had begun in the 1960s. Life in Yushin Korea was irrevocably marked by the radical suppression of civil rights, including the right of public assembly, by a tightly controlled state elite. At the same time, the South Korean economy – helped in large part by the U.S. and its need for material support during the Vietnam War – increasingly affected the general direction of national policy. The state was run by a technocracy whose ‘paramount concerns were effectiveness and performance’ and whose policies were intended to mould individual behaviour to better serve the economic goals it set.1

Visual art was by no means exempt from this pursuit of efficacy and achievement. From approximately 1973 the national documentary paintings project – the Korean state’s largest continuous visual arts project that resulted in the production of hundreds of figurative oil paintings commemorating various scenes of military and historical glory – expanded to include scenes of economic achievement.2 The Kukjŏn, the juried National Art Salon held annually in Seoul since 1948, tended to include artworks that featured images of a rapidly industrialising Korea; this was particularly well demonstrated in the many photographs of factories, pipelines, and ships selected to represent Korean art. In January 1972 the government enacted the Cultural and Arts Promotion Law, yet another state directive aimed at helping ‘national culture flourish’.3 The law supported cultural preservation in the name of upholding Korean traditional culture, but also established a central funding body, the Korea Culture and Arts Foundation.4 However, artists working outside the recognised categories of Western-style oil painting, ink painting and sculpture received little government support. Many instead pooled their resources and formed unofficial support networks of their own. Groups like Avant-Garde (A.G.) and Space and Time (S.T.) held public exhibitions, which like any form of public display or opportunity for public assembly in Yushin Korea, was subject to police surveillance.

These independent groups attracted the notice of foreign audiences, a point not lost on a state eager to improve its international standing in a shifting world order. Indeed, one of the goals of the Cultural and Arts Promotion Law was to improve the quality of contemporary Korean art so that it could ‘hold its own in international cultural circles’.5 It was not surprising, therefore, that the state agreed to allow artists who they disapproved of, such as Lee Kun-yong, to participate as national delegates at international biennials and triennials during the 1960s and 1970s.

Despite and because of these international opportunities, it was not always clear to artists what was considered ‘acceptable’ by the state. In short, these were confusing and often dangerous times. Presenting work outside a recognised exhibition space could result in an artist being put under surveillance or even imprisoned, although not always. Park’s instigation of new ‘emergency decrees’ in the spring of 1975 expanded state power so much that it effectively made any kind of action grounds for severe punishment. The question ‘What could be done?’ became more fraught than ever before, especially after the issuance of Emergency Decree No.9, which banned campaigns against the Yushin system and permitted law enforcement authorities to arrest and detain people without warrants. In practice, the decree gave the government and its agents carte blanche to prohibit almost any activity conducted in a public space without warning or justification. This was particularly reflected in police and museum officials’ attitudes towards performance; more than any other artistic medium performance provoked the most incidents of direct state interference. In almost all cases the state did not provide a reason why an exhibition was shut down or an artist put under surveillance.

Fig.8

‘Why Don’t We Measure This?’

Photograph printed in Chosŏn Ilbo, 10 March 1973

Photo: Choi Duk-chun

The absence of justification in a society purportedly based on the rule of certain laws reflected an arbitrariness that rendered nearly every action suspect. In such a context, performance, or art involving the execution of a particular action or task, acquired particular significance. Its relevance was intensified by the spectacle of legal enforcement that was as much intended to render viewers complicit with state mandates as it was intended to deter viewers from reproducing the prohibited activity. Take, for instance, an image of a policeman measuring the length of a young woman’s miniskirt at the Myongdong police station in downtown Seoul (fig.8). It shows the policeman holding a ruler against a portion of exposed flesh between the middle of the woman’s thigh and just below her knee. Photographed by the journalist Choi Duk-chun on 10 March 1973, the day that the newly expanded Minor Offence Law became enforced, it appeared in that day’s issue of the popular daily newspaper Chosŏn Ilbo. The Minor Offence Law made subject to police scrutiny and punishment men whose hair exceeded a certain maximum length and women whose skirts failed to reach a certain minimum length. Although violations of the law were not considered particularly serious, the spectacle of its enforcement became a memorable symbol of the eroded division between the public and the private during the Yushin period.

Accompanying the photograph was a caption – ‘why don’t we measure this’ – the wording and tone of which slyly positioned the reader on the side of the state. The view from the camera also placed readers right behind the police, with a ruler separating them from the woman on the wrong side of the law. The act of measuring is put on grand display, the policeman grasping the ruler as if it were the source of his authority. The act reads like a staged gesture while the moment seems too pronounced and prolonged for what in reality took place in an instant in the most banal of settings.

Compare this to Body Drawing 76-01, specifically the final image showing Lee standing in front of his newly reconfigured plywood board (fig.7). The work confirms his height, and by extension his existence in the world. In contrast, the woman in Choi’s photograph turns away from the viewer, made to stand as if she were a specimen only worth noting because of her presumed deviance. With evidence of her personality completely suppressed, she is only recognised as a ratio of exposed to concealed flesh. The ruler’s conspicuous placement leads the eye to perceive the body not as a holistic totality, but as so many parts, divided by the hemline of her skirt and the tops of her boots. In Body Drawing 76-01 Lee makes the plywood conform to his bodily proportions and to what they permit him to do physically. He stands next to the stacked panels at a distance just far enough for viewers to consider his body and his work as two halves of the same tableau. Seen against Choi’s 1973 image, the photographs of Body Drawing 76-01 emphasise the political urgency of aesthetic decisions intended to produce a particular kind of viewing experience. The dimensions of the panel, the use of the marker and saw, the act of drawing lines on a rough plywood surface and even Lee’s decision to wear street clothes all contribute to a viewing experience that allows the images reflecting the actions of the state to be reconsidered, and asks what being present might mean despite these actions.

In specifying what was meant by action in the context of Yushin Korea, two aspects about this comparison stand out. One is how clearly it foregrounds the close relationship between photographs taken of a specific performance and those meant to record a newsworthy incident. The first of what would be seven iterations on a theme, Body Drawing 76-01 was intended to be performed live in front of an audience. Yet it was the photographs that subsequently assumed a special significance, especially given how they were often taken to mirror, or at least allude to photographs taken specifically for newspapers. Although witnessing an actual performance is profoundly different from experiencing it through one or even a brace of still photographs, it is worth keeping in mind that Lee Kun-yong and his closest associates placed as much, if not more emphasis on the photographs documenting their activities. As the philosopher Walter Benjamin famously declared, ‘the audience’s identification with the actor is really an identification with the camera’.6

Lee relied upon those who recorded, edited, and pieced together fragments of his performance works into composite form because he recognised how his audiences interpreted civil society, politics, and class through the visual culture created by the camera and disseminated in newspapers and to a lesser extent, television. Renowned drama critic Han Sang-chul might have been discussing performance artists when he emphasised the need to reveal ‘the extent to which that considered as truth are in fact fabricated lies’.7 Likewise, how particular kinds of media affected the documentation of performances was central to the subsequent effect and agency of each performance. Together with the actual plywood board Lee used, the photographs Sung took of Body Drawing 76-01 were publicly exhibited at the Publishing Culture Center in Seoul.

Equally notable is how this comparison openly foregrounds the image of the single, physical body as the crucible for thinking about the possibilities of action in Yushin Korea. As vividly reflected by the restrictions imposed on skirt and hair length, the state obligated its citizens to conform to a set of arbitrary norms. This in turn meant the systematic denial of personal autonomy; one must submit under pain of punishment. Such denial, however, begged the question as to what actions, in fact, were permitted, which many Korean performance artists answered by investigating the connection between the physical body (sinch’e) and self consciousness via a recognition of what the body could or could not do. Performance art in Yushin Korea thus encompassed larger questions regarding the nature of artistic agency, a critical task at a time when doubt was cast over the viability of outright protest or critique.

Happening – event – incident

Fig.9

Photograph of A Happening with a Vinyl Umbrella and a Candle, Union Exhibition of Young Artists, Seoul, 1967

Courtesy the artists

The social import of performance art in Korea is vividly manifested by the Korean terms used to refer to such works. P’ŏp’omŏnsŭ, the romanised term for performance, was not widely used until the 1980s. Instead the earliest performances, which took place in the late 1960s, were often called ‘happenings’, a term likely borrowed from Allan Kaprow, whom the Korean press described in 1968 as an artist who proposed ‘unifying visual art and theatre in the context of an environment’ and whose works stressed ‘the process of expression’ over the ‘outcome of such expression’.8 Happenings in Korea were variably defined as ‘spontaneously occurring incidents’, as ‘struggles to leave the world of art for the society around it’, and as ‘scenarios taking place within a designated place in real time’.9 The most important early happenings took place in December 1967 at the Union Exhibition of Young Artists (Ch’ŏngnyŏn chakka yŏllipjŏn), where members of the Zero Group (Mudongin) and the New Exhibition Club (Sinjŏndongin) presented A Happening with a Vinyl Umbrella and a Candle (fig.9). For this work participants held a vinyl umbrella and a candle while singing ‘Blue Bird’ (Saeya saeya p’arangsaeya), a popular folk song that was allegedly written as a nationalist rejoinder to Japanese imperial ambitions towards Korea in the late nineteenth century.10 The umbrella was set aflame with the candle, then torn and destroyed. In his overview of performance art in Korea, Lee Kun-yong alleged that the umbrella symbolised the ‘umbrella’ of U.S. military protection while the ‘Blue Bird’ anthem was sung to remind audiences of present threats to Korean political and cultural sovereignty.11 In 1968 the critic Yoo June-sang described happenings such as this as attempts to escape the ‘pressures of mechanisation and pragmatism’, motivated by the state’s relentless push to fully industrialise the economy.12

By the 1970s the term ‘event’ (ibent’ŭ) began to be used increasingly to refer to performances. This change in terminology was partly strategic; Lee suggested that publicising an exhibition as an event would make it more likely that performances would be recorded.13 Meanwhile his friend Lee Kang-so claimed that using ‘an ambiguous foreign loan word like event’ was a default response to the marginalised place of performance art in the Korean art world.14 The insinuation was that by using such a term, performances became explicitly connected to an expanded, international art world. Art historian Kang Tae-hi has claimed that the term ‘event’ was imported from Japanese artists, including those involved in Fluxus, the international, multidisciplinary network of artists whose works frequently involved written scores indicating how and when certain actions would be performed.15 Another possible source for the term may have been Japanese artist Kishio Suga, whose own ‘events’, involving commonplace materials like rope, stone and wood, were seen by the Korean artist Kim Ku-lim in connection with Suga’s solo exhibition Fieldology at Gallery 16 in Kyoto.16 Shortly thereafter Kim mentioned Suga’s events to his friend Lee Kun-yong, who from roughly August 1975 became the first Korean artist to consistently refer to his performances as events.17 As with many Fluxus event scores, Lee’s written notations emphasised the sequence of actions, yet his were not formal scores per se but sketches visualising what the performance might look like, with several resembling crude animation or film storyboards. In choosing to substitute the term ‘happening’ with ‘event’, Lee claimed that the former was too literal to adequately account for what he regarded as fundamental to performance: how the idea of place affected the capacity of bodily movements to express meaning, that is, to become gestures.18 Here he diverged from Suga, who defined events as ‘a rejection of the idea of performance as a phenomenon that arises from the movement of people’.19

In his overview of key developments in 1960s Korean art, the critic Oh Kwang-su argued that ‘the initial meaning of happenings changed as the actions undertaken [by artists] started to [more directly] reflect distinct social issues’.20 By the mid-1970s, when Lee Kun-yong began to refer to his performances as ‘incidents’ (sakkŏn), a procession of sudden, short-lived and in many cases unpremeditated acts had taken place that seemed to define the passing of time itself.21 Indeed, for the average citizen daily life became measurable in terms of discrete incidents: on 21 January 1968 a group of North Korean commandos almost succeeded in assassinating Park Chung-hee at the Blue House, his official residence; two days later North Koreans captured a U.S. naval spy ship in what became known as the Pueblo incident; and most infamous of all, 17 October 1972 when Park declared martial law. At the same time, the state increasingly relied on kidnappings, executions, and torture to perpetuate its authority.

Fig.10

Kang-kuk-jin, Chŏng Ch’an-sŭng and Jung Kangja

Murder on the Han River 1968

Courtesy the artists

Many performances closely resembled these incidents in what appeared to be an intentional attempt on the part of artists to merge their art with general Korean society outside of state-mandated channels. For example, in October 1968 Kang Kuk-jin, Chŏng Ch’an-sŭng and Jung Kangja staged Murder on the Han River on the banks near the Second Han River Bridge (known since 1982 as Yanghwa Bridge) near western Seoul. Holes were dug in the sand, into which the artists were partly buried as if being prepared for a live sacrifice (fig.10).22 In the close-up images that captured the performance the bodies appear frail but strangely resilient.

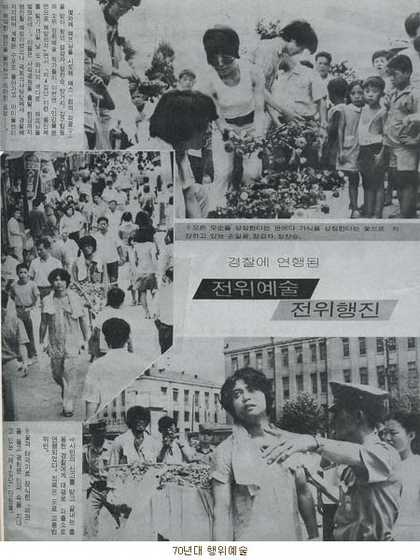

Fig.11

‘Avant-Garde Art, Avant-Garde Parade: March Under Arrest’, Weekly Woman (Jugan Yeoseong), 26 August 1970

© Chugan Yŏsŏng

More pointed still was Funeral for Established Culture and Art, staged by the Fourth Group, a casual association of visual artists, a fashion designer, a scriptwriter, a journalist, and even a Buddhist monk.23 The performance took place on 15 August 1970, a public holiday commemorating Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial occupation, and was intended to mark the moment when Korean culture would also be freed from what the group called ‘the wrongheaded system of the establishment’.24 Five members (Kim, Chŏng Ch’an-sŭng, Jung Kangja, Kang Kuk-jin and Son Il-gwang) decided to stage a ‘funeral procession’ that involved carrying a coffin shrouded in the Korean flag from Sajik Park in downtown Seoul, not far from the U.S. Embassy, and along Seoul’s busiest street towards Kwanghwamun, the main gate of the royal residence. The choice of sites was of particular significance; as Kim Ku-lim recalled some years later the group ‘tried to erase the gap between the arts and the public’ by weaving the performance into the fabric of daily life, thereby avoiding the sanitised exhibition contexts of institutions controlled by the state.25 The methodical pace of the carefully choreographed procession contrasted with the fast, free-flowing swarms of people enjoying a rare day off from work, which, despite the fact the participants were evenly separated to deflect accusations of wrongful public assembly (then a serious crime under Park’s increasingly wary regime), prompted the police to intervene and quickly put a halt to the proceedings (fig.11). After failing to convince the police that the performance was in fact art, the group’s members were found guilty of obstructing traffic and violating street laws. Legally speaking the transgression was minor, but the repercussions were significant and even excessive. Kim Ku-lim recalled being harassed and followed by a police detective for about six months afterwards, while the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA) allegedly raided his father’s house, an act so disproportionate to the perceived crime that it served only to highlight the state’s pathological unwillingness to accept the sight of a rival spectacle, no matter how small or temporary.26

The Fourth Group soon disbanded, but only after attempting one last action. On 22 August 1970 members of the group gathered at the state-run Information Center where an exhibition of Jung Kangja’s works was due to take place. According to the critic Yi Ku-yŏl, a sign affixed to the exhibition poster read: ‘This show will not be held as planned due to the orders of the authorities. As an artist, I join the audience in lamenting this state of affairs. Jung Kangja.’ Upon entering the exhibition space Yi found members of the Fourth Group in a state of ‘silence’. Yi Kwi-hwan, the government employee responsible for the Information Center gallery told the critic that the exhibition had been closed prematurely, largely because the Fourth Group were notorious ‘violators of social order’. After hearing this explanation Yi went back to the artists who allegedly responded that ‘we have nowhere to stand’.27

In 1977 Lee Kun-yong’s younger colleague Chang Suk-wŏn distinguished between events based on incidents and those based on accidents (sago).28 The latter were spontaneous and uncontrollable occurrences whose participants did not form any meaningful relationships with one other. Incidents, on the other hand, were occurrences governed by a certain kind of logic able to transform bodily actions into gestures, which could encourage viewers to physically interact with and hopefully relate to one another. This in turn resonates with Lee’s definition of an event as ‘a phenomenon of critique towards present culture and society’.29 His works involving the repetition of basic physical actions appear to have been calculated so as to induce audience members to copy the same movements, facilitating a ‘collapse of the division between art and life’.30

Anyone believed to be endangering this division ran the risk of state scrutiny. Officials at the National Museum of Contemporary Art condemned performances as ‘heretical’, a word that directly reflected the Korean artistic establishment’s firm commitment to the orthodoxy of figurative painting and sculpture.31 Sung Neung-kyung has alleged that a day before the opening of Three-Person Event at the Press Center in Seoul in 1976, he and fellow participants Lee Kun-yong and Kim Yong-min received a call from detectives ‘nervous’ about what the ‘event’ entailed.32 The political philosopher Hannah Arendt has argued that twentieth-century police states were in part places where the limits of ‘the real’ and ‘the possible’ were replaced with a fictional world.33 While Yushin Korea was far from being the kind of totalitarian regime written about by Arendt, the replacement she mentioned would have been apparent to Korean artists familiar with the national documentary paintings project promoted vigorously by the Yushin state. Depicting subjects of economic and military glory, the paintings that comprised this project reflected what Arendt called the ‘totalitarian fiction’ of foreseeing as possible that which was impossible. In contrast, performance artists like Lee produced works that focused on the limits of what a single person could achieve physically, and thus served to undermine the impossible fictions of the state and its obsession with progress.

‘Artists who act’

The suspicion directed towards performance may also have been aroused by an article published in 1968 in the widely read Tonga Ilbo newspaper, which described performance art as a phenomenon that originated in ‘New York, the center of materialist culture’, and was characterised by attitudes of ‘anti-traditionalism’ and ‘anti-civilization’ exemplified by artists’ ‘penchant for using the waste of urban culture as materials for their works’.34 The specific use of the phrase ‘anti-traditionalism’ may have triggered alarm bells in the minds of state officials charged with upholding the image of a grand and continuous Korean tradition: an artist could be modern or even non-traditional, but never anti-traditional.

At issue here was the question of authority, which for Korean performance artists was greatly affected by a Korean art establishment heavily supported by the state. Composed almost entirely of male professors practising oil or ink painting, and based at either Seoul National University or Hongik University, the deeply stratified art establishment not only determined the selection of works in prestigious venues such as the Kukjŏn, but also access to state and even private sources of funding. In terms of artistic production, the establishment favoured painting, a preference reinforced by a centuries-old bias against sculpture, whose relatively low status vis-à-vis painting was encumbered by its associations with menial labour. As seen from the works chosen for the Kukjŏn or the forms of depiction taught at university level, many established artists favoured gestural abstraction of the kind that had been popular in the late 1950s.

By the late 1960s, however, younger artists began producing work that did not readily conform to the expectations of what painting or sculpture should look like. Many of these artists had studied painting but collectively refused to only produce painted images on flat upright supports endorsed by the Kukjŏn, thereby rejecting the traditions and conventions of the artistic establishment. Reflecting the inability of the prevailing artistic infrastructure to accommodate this refusal, their works were simply classified as ‘experimental’ (silhŏm). Many of these works were made under the auspices of the small artists’ groups that proliferated in the late 1960s and early 1970s, including the A.G., founded in December 1969, and the S.T.35 Largely comprised of graduates of Hongik University, groups like these brought together a number of artists who shared as an objective ‘the investigation and creation of a new plastic order’ that would ‘contribute to the development of Korean artistic culture’.36

In 1967, just after the performance of A Happening with a Vinyl Umbrella and a Candle, twenty members of the Zero and New Exhibition groups took to the streets to protest against what they regarded as the conservatism of the Korean artistic establishment. After congregating in front of Seoul’s city hall, the artists went to Sejong-ro, Chongno 2-ga, Samil-ro and then finally to Sogong-ro, all major thoroughfares in downtown Seoul. Eventually the procession was halted by police who detained some participants for questioning.37 While it can be regarded as a genuine protest, the event was more of a publicity stunt aimed at getting city residents to see the show. The placards promised free admission and insisted that ‘Contemporary art is friends with the public’ and argued that ‘National development begins with active promotion of the arts’. Among the few photographs taken of the event, one shows a placard that simply says ‘artists who act’, a legend that had particular resonance at a time when the status of the artist seemed particularly compromised.

Why ‘act’ and not ‘make’? An answer to this question was proposed in 1975 by the critic Park Yong-sook, who identified this generation of Korean performance artists as a group forged together by their shared refusal of an earlier avant-garde legacy based solely on reifying the objecthood of painting.38 He was likely referring to the institutional ascent of gestural abstraction known as Korean informel, which first appeared in the late 1950s and came to dominate exhibitions of Korean art at international biennials over the subsequent decade. These delegations were funded and sponsored by the Korean government, which implicitly gave gestural abstraction the imprimatur of being an official art. Nearly every student enrolled in an oil painting department in a Korean university between the late 1950s and mid-1960s received classroom instruction in informel-type painting. The artist Pak Yŏng-nam claimed that the young artists who participated in A Happening with a Vinyl Umbrella and a Candle did so not only to reject the canvas but also pre-existing notions of art’s possible functions: ‘instead of producing only decorative works, they wanted their art to jump directly into the field of life.’39

The turn to performance was also facilitated by the international ambitions of the Korean art world in general. The critic Bang Geun-taek suggested that performance in Korea arose partly from artists’ interest in earthworks, and especially outdoor works that involved hole digging or other forms of physical labour, the execution of which required only rudimentary abilities.40 Although never cited explicitly, the focus on the physical body as both material and metaphor of the self echoed the convergence of body art and performance exemplified by the works of Yoko Ono, Vito Acconci and Carolee Schneemann. Nam June Paik was a popular subject in the mainstream Korean press as the first artist of Korean descent to gain prominence in the international art world. Throughout the late 1960s short articles reported eagerly on the ‘nude concerts’ he held with his long-time collaborator Charlotte Moorman, with at least one insinuating that these works were partly responsible for the sudden appearance of performance art in Korea in 1967.41

Most important of all was the keen interest professed by artists like Lee Kun-yong in the works of Jackson Pollock. For Lee, Pollock’s appeal lay in how his works appeared to underscore artistic creation in that they were less about ‘realising one’s ideas’ than about the enactment of ‘bodily movements’.42 A prolific critic, whose essays represent some of the most important published work on early Korean performance art, Lee claimed that it was the proliferation of informel-type gestural abstraction in late 1950s Korea that first underscored the importance of gestures in the Korean art world.43 His interest strongly recalls the argument made by Allan Kaprow in his seminal 1958 essay ‘The Legacy of Jackson Pollock’, in which Kaprow described Pollock’s move away from ‘the confines of the rectangular field’ in favour of ‘an experience of a continuum going in all directions simultaneously, beyond the literal dimensions of any work’.44

While escaping the canvas was important, Lee’s primary ambition was to create work with sensory immediacy in real time to be experienced by a live audience. For Lee, performances involved more than ‘composing spaces or producing objects’; they also meant rethinking ‘the structures through which the world came to be realized’.45 In addition, the focus on the body in Korean performance arose from a markedly different set of concerns to those that led to its emergence in the New York art world. Citing Sol LeWitt, the critic Peter Schjeldahl claimed that the use of the body was a response to the sense of ‘confusion’ that characterised the late 1960s in America, which LeWitt described as an implosion: ‘if we’re imploding … we’re pulling in, let’s see how far can we pull in. And finally you get to your body as the horizon.’46 Conversely, the turn to the body in Korean art was a tacit response to a social order that apparently sought to restrict what the body could do. Increasing state surveillance and propaganda exhorting citizens to put the nation before the self fatally compromised the idea of personal space or sovereignty. As life under Yushin Korea became even more repressive, artists including Lee Kun-yong, Sung Neung-kyung and Lee Kang-so focused on what went largely unnoticed: habitual actions that everyone performed on a daily basis. Most importantly, their performances are notable for the degree to which they made plain their control over both the circumstances under which they performed their actions and how they were eventually transmitted to an audience, whether through carefully staged photographs or real-time events.

Outstanding in this respect was the short-lived activities of the Esprit Group, one of a growing number of newly formed artists’ groups that included both painters and sculptors. Comprised of recent graduates of the painting and sculpture departments of Hongik University who were ‘left out’ of the activities of the A.G. and S.T., whose members were somewhat older, the Esprit Group was interested in having their artistic gestures be read as political ones that could explicitly resonate with contemporary social issues.47 This meant affirming a sense of self in an era of ‘restriction’ defined by arbitrary rules that stipulated what not to wear, read or do.48 In the catalogue of their inaugural exhibition the artists stated: ‘Each of our gestures must reflect an attempt to overcome meaninglessness and also serve as evidence affirming the presence of our selves.’49 The group emphasised personal volition, which in their works often took the form of deliberate inaction, running counter to the state’s incessant calls for action. In doing so they also sought to emphasise how the state used the inert body as proof of its own permanence.

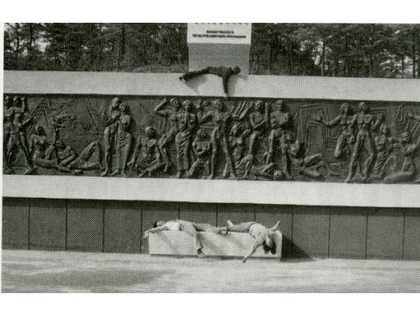

In 1974 the group’s members, most of whom were sculptors by training, mimicked the poses of figures depicted on the bronze relief erected by the South Korean Ministry of Defence in October that year to commemorate Philippine participation in the Korean War. The relief was borne from a large-scale government effort to commemorate various historical figures, the best known perhaps being the fifteenth-century naval hero Yi Sun-shin, whose statue was erected in 1968. Despite its stated purpose, a plaque accompanying the Philippine memorial described the scenario depicted as ‘the desperate struggle of the Korean people to overcome frustration and win their freedom and establish peace’.

Fig.12

Espirit Group

Untitled performance 1974

Courtesy the artists

The artists, wearing ordinary street clothes, did not mimic the poses exactly but chose to emphasise the exaggerated drama of the sculpted scene. As the photographs of the action reveal, the artists’ physical interventions, which undermined the gravitas of the content and the material integrity of the bronze, make it almost impossible to regard the frieze as its own internally contained, autonomous world. One photograph shows three members sprawled on and before the commemorative frieze: a student in black lies on top, his right arm and leg loosely draped over the limestone border, his hand just crossing the point at which the edge of the limestone gives way to the frieze, compromising the limestone’s capacity to frame the scene (fig.12). Below the frieze two other artists lie precariously on a limestone bench, arms and legs splayed. They appear almost completely inert, unable to sit or stand upright. But their stillness is different to that of the bronze figures, whose rigid poses conveyed the state’s desire to promote the image of a strong and timeless Korean nation. In contrast, the artists appear lifeless but real, their soft flesh expressing an authenticity that the hard bronze cannot.

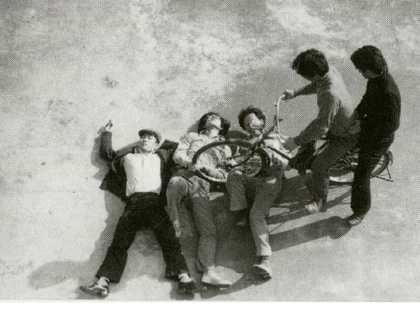

Fig.13

Espirit Group

Untitled performance 1974

Courtesy the artists

A related performance shows two members riding a bicycle over three of their compatriots, who lie directly on the ground (fig.13). Taken from above, the photograph emphasises the supine positions of the bodies, pinned to the ground, in contrast to images of upright bodies propagated by the state, which served as metaphors for a healthy, active nation. The bicycle appears to press into the bodies, which do not remain still but visibly flinch under the pressure, most notably the young man on the right who bends one knee and cranes his neck. These are not the silent, timeless bodies of Yi Sun-shin or those on the commemorative frieze, but are live, real and in pain.

Drawing the lines of engagement

The potential of performance to allegorise the forces of political oppression was most vividly realised by Lee Kun-yong. Born in 1942 in Sariwŏn, Hwanghae province in what is present-day North Korea, Lee was among the first generation of Korean artists to grow up without direct memories of a colonised Korea. While he too suffered from the devastation of the Korean War that permanently separated him from his birthplace, Lee’s formative years were defined by the political ascent of Park Chung-hee from 1961. While attending Paeje High School in Seoul he developed a keen interest in linguistics and philosophy, and in particular the writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein, which led him to paint a large portrait of the philosopher.50 In 1963 he enrolled in the Western oil painting department at Hongik University where gestural abstraction was quickly absorbed into the curriculum.51 By the time he graduated in 1967, however, Lee was among those younger artists exhausted by the endless production of informel-type painting. He addressed his situation in 1969 by co-founding Space and Time with his friend the critic Kim Bok-young. Active until 1981, the S.T. was keenly proactive about studying overseas artistic developments and organised regular seminars moderated by the critic Yu Kŭn-jun on topics selected by Kim.52 Especially popular was Joseph Kosuth’s 1969 essay ‘Art After Philosophy’, which was translated and circulated after the second exhibition of the S.T. in June 1973, and Lee Ufan’s book In Search of Encounter, parts of which were translated by the critic Lee Yil for a meeting of the group in October 1970. Lee Kun-yong was intrigued by Lee Ufan’s critique of a culture ‘excessively’ focused on the act of ‘making’, a statement that struck a chord with him and other Korean artists disillusioned with the state’s mandate for industrial production.53

Exhibitions comprised a large part of the S.T.’s activities. Held in spaces rented from both private galleries and buildings owned directly by the state, the S.T. shows often featured performance. Four of the seven known versions of Lee’s Body Drawings series were shown or performed at the fifth S.T. show Objects and Events at the Press Center in Seoul in November 1976. S.T. members also showed in the annual Taegu Contemporary Art Festival, where some of the most important performance-based works in Korea were premiered.54 Held from 1974 to 1979 and organised by a revolving committee of artists with little interference from local or national authorities, it took place in the south-eastern city of Taegu where state scrutiny was noticeably less intense than it was in the capital.

Of primary concern for performance artists in Korea was the issue of communication (sot’ong). Many artists such as Sung Neung-kyung regarded the state’s approach to communication as little more than a cacophonous inventory of catchphrases and statistics: ‘Living in the Korea of that time, I had no idea what it meant to live in a post-industrial society’, recalled Sung.55 State benchmarks like ‘a GNP over three thousand [US] dollars’ had ‘absolutely no meaning’.56 So fraught was the matter of communication that the critic Park Yong-sook openly commented that ‘the [artistic] language for refusal and communication became one and the same’.57 Fear of possible reprisal may have stopped him from naming the object of this refusal, but the implications were clear; only a few months earlier the state violently quashed a nascent movement to defend the freedom of the press.

For artists like Lee Kun-yong who came to performance at the height of Yushin surveillance, creating art first meant recognising how state regulation and vigilance set the boundaries of what actions were in fact possible. The arrest of the Fourth Group and its members clearly demonstrated that direct intervention in the streets was not viable. Neither was it possible for artworks to inspire the kind of collective action that would effect political change. Yet the limitations placed on activity were no excuse for shirking what many performance artists implicitly regarded as their personal responsibility to do something. In many cases, this entailed making their works as physically and psychologically accessible to ordinary individuals as possible. Several performance artists made a point of inviting people not affiliated with the art world to form audiences for their work. Even more important was how artists turned to bodily actions that were distinctly ordinary, unspectacular and, in Lee’s words, ‘unnecessary’.58 Indeed, most performances undertaken between c.1972 and 1979 involved little more than the repetition of very basic actions including scratching, erasing, eating, breathing, drinking and walking. Small wonder then that many Korean artists and critics began to describe performance art increasingly as ‘gesture art’ (haengwi yesul). Sung Neung-kyung observed that the repetition of a single gesture made it possible to ‘acknowledge gestures as gestures’, which allowed viewers to grasp a situation on their own without external interference. This sense of openness and self-understanding had particular resonance at a time when personal autonomy was in short supply.59

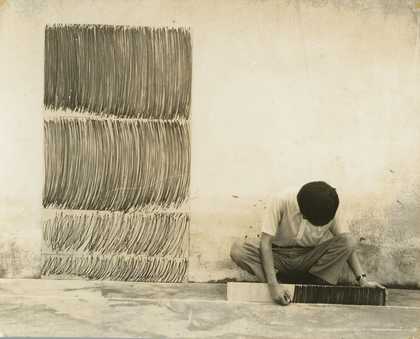

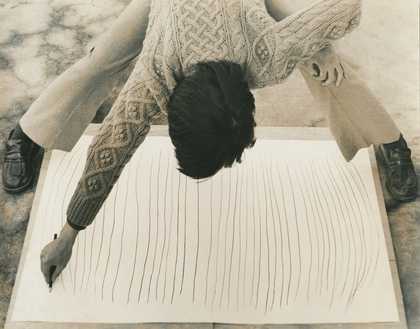

Fig.14

Lee Kun-yong

Body Drawing 76-05 1976

© Lee Kun-yong

Photo: Sung Neung-kyung

These were also actions that ordinary viewers could easily follow and duplicate. Many performances were in fact documented in ways that encouraged viewers to reacquaint themselves with their own bodies. The intentionally sequential photographs of Body Drawing 76-01, for example, resemble a step-by-step manual illustrating how to reproduce the actions at home. These actions were about legitimating what ordinary individuals could do in marked contrast to the state, which propagated ideals that were impossible for its citizens to emulate, as individuals and as a nation. For Body Drawing 76-05, undertaken in the same group exhibition in which he exhibited photographs of Body Drawing 76-01, Lee stood with his feet spread apart around a plywood panel, onto which a paper sheet was attached. Supporting himself by placing his left hand on his left leg, Lee held a piece of charcoal in his right hand, using it to draw lines on the paper underneath him from top to bottom. He began by drawing a straight line that bisected the paper, then repeated the action until he reached the sides (fig.14). As if uncertain of his own capacities or in defiant response to an invisible naysayer, Lee shouted ‘I will draw straight lines!’ in an increasingly louder voice as the performance continued. But as the artist’s hand moved closer to the edges of the paper it became more difficult to keep his balance and draw lines that were straight. Contrary to the steadiness of the first line, those at the edges were curved and most likely drawn at a much slower pace. Acknowledging this change, Lee amended his words, declaring ‘I am drawing upright lines!’

In 1976, the year immediately following the Yushin state’s suspension of numerous civil liberties, the issue of action was steeped in profound doubt. After performing Body Drawing 76-05 Lee was accosted by two government agents who took issue with the artist’s change of language from ‘straight lines’ (chiksŏn) to ‘upright’ ones (kodŭn sŏn). ‘What do upright lines mean?, they asked.60 While the agents may have felt uneasy about the word ‘upright’, perhaps because it suggested a connection to a state apparently bent on suppressing even basic individual freedoms, for Lee the Body Drawings series asked whether it was still possible to undertake even the most basic physical acts. Outright protest was futile, not because it would be short-lived or because of the threat of punishment, but because it would too easily play into an authoritarian culture that revolved around a polarising, ‘us-versus-them’ logic. Instead, it was more productive to rekindle faith in the possibility of doing.

A collection of notes written by Wittgenstein just prior to his death in 1951 may provide a framework for thinking about Body Drawing 76-05. Written in response to George Edward Moore’s argument on behalf of common sense, Wittgenstein’s ‘On Certainty’ refuses the idea of self-evident axiomatic truths, a refusal that Lee and his colleagues would have endorsed. Their performance of actions so basic and ordinary as to be mimicked by almost anyone was undertaken in order to establish a deeper connection with an audience, not necessarily because such performances were ‘intrinsically obvious or convincing’ (as Wittgenstein might say), but because audiences living under the restrictions of Yushin Korea would have recognised them as being among the few actions not subjected to scrutiny or punishment.61

Or were they? One might believe that standing, stretching or eating could be done freely. But how strong was this belief at a time when it was never quite clear what was permitted and what was not? Lee responded to the government agents who accosted him, asking them if it was a ‘crime’ to ‘draw a straight line’.62 He and colleagues like Sung Neung-kyung performed basic acts in order to confirm for themselves that they could. The fact that their performances were documented in multiple photographs each showing single discrete acts affirms the importance of experience. To borrow again from Wittgenstein, it was not enough to say ‘I know’; more crucial was to test and record one’s experiences rather than accept the claims made by human authority.63

In an important essay published in the 1976 issue of Tongdŏk Misul, the critic Park Yong-sook claimed that while ‘events are comprised of basic actions, it does not follow that the continuous enactment of these actions must necessarily amount to a specific meaning or purpose’.64 This meant rejecting the purpose to which artworks had ordinarily been put, namely, the idea that they should represent or express something other than their constituent materials.65 In Yushin Korea, where time was measured in five-year plans, quarterly gains, annual benchmarks and other goal-oriented markers, insisting on an artwork’s purposelessness was significant. It may not exactly count as resistance, but it nevertheless offered a space within which to think about visual art beyond questions of practical function, progress and use.

Lee Kun-yong condemned the iteration of explicit purpose as a form of narcissism.66 He spoke harshly of what he described as the pointlessness of artists who deluded themselves into thinking that their work somehow addressed something outside of itself, declaring that an artwork that directly engaged with politics was really just a means of blatant self-promotion.67 A better approach, according to Lee, was to simply reject meaning altogether, to in effect emphasise ‘how’ over ‘what’.

On this point, the non-indexicality of his marks in the Body Drawing series is telling. His scribbles are hardly the result of a technique; in fact, technique was the enemy, hence the deliberate shift from painting to drawing, a medium distinguished by its comparative marginality. Drawing was never given the dignity of autonomy, particularly in Korea where it was long regarded simply as a preliminary step towards to the creation of a painting. Lee’s turn to drawing can be seen as a refusal of this hierarchy and its implications: ‘I began drawing because of my fundamental suspicion concerning the history of art and its meaning’, he wrote in 1979.68 In his report of a group discussion held on the occasion of the fourth S.T. show in 1975, Park Yong-sook stated that artists like Kim Ku-lim and Lee Kun-yong differed from their painting-obsessed colleagues by focusing on mark-making rather than on picturing.69 Marks enacted in the course of painting were done to form a picture, a definition that anticipated how fellow critic Oh Kwangsu defined ‘happenings’ as an ‘escape from the trap set by the demands of the pictorial surface’.70

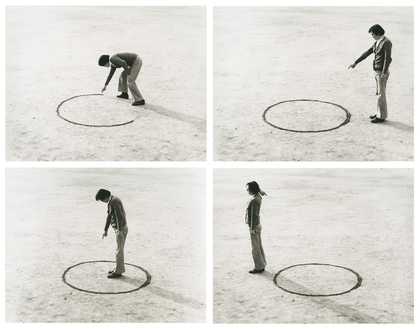

Fig.15

Lee Kun-yong

Logic of Place 1975

© Lee Kun-yong

Photo: Yi Wan-ho

For the fourth A.G. show in December 1975, and later for Three Person Event in 1976, Lee performed Logic of Place. But before actually performing the piece he had Yi Wan-ho take a series of documentary photographs of himself executing the work in stages at Hongik University (fig.15). The first shows Lee drawing a circle in the ground using a long nail, He is then seen standing and pointing at the circle. At this point in the actual performance he uttered the word ‘there’ (kŏgi), before stepping into the circle and shouting ‘here’ (yŏgi). Lee then stood outside it again, pointed behind his shoulder in the direction of the circle and uttered ‘over there’ (chŏgi). Returning to the circle, he said ‘here’, ‘there’ and ‘over there’ before finally walking around the circle shouting ‘where’ three times in succession.71

In Yi’s photographs the soft dirt of the university schoolyard yields obligingly to the pressure exerted by Lee, the resulting incision in the sandy field appearing as indelible as a line engraved in stone. He points down at the ground and occupies the circular space with an insistent ‘here’, as if trying to compensate for the dispossessed members of the Fourth Group who had ‘nowhere to stand’. Lee’s intentions for this work were quite different from those of the American artist Vito Acconci, who in his 1971 video work Centers points his finger directly at the viewer for a sustained length of time (more than twenty minutes). Concerned with how actions depend on their mediatisation, Acconci’s pointing gesture was not so much about establishing a relationship with the viewer than it was about drawing attention to the reification of the surface on which images are projected. In Lee’s case, the acts of marking, pointing, walking and reciting were intended to affirm what was true, that ‘[Yushin Korea] was a society of lies. Trying to figure out what in fact was true became the most important priority.’72 For Lee and his closest interlocutors, this meant encouraging viewers to think about what it was they were actually seeing. During the actual performance of Logic of Place Lee noticed that audiences continued to stare at the drawn circle, even after he had disappeared from the scene. But the artist has stated that in repeating the word ‘where’, his aim ‘was to question the idea of place’.73 Doing so required making a connection between the viewer and the world in which he or she lived, a connection reified by the gesture, the pointing figure.

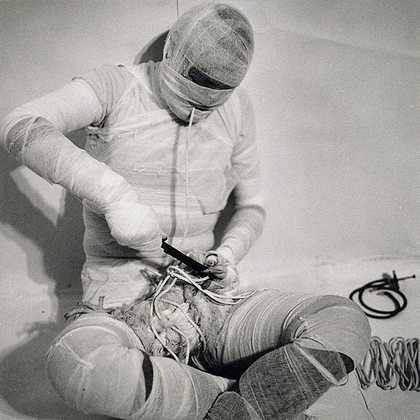

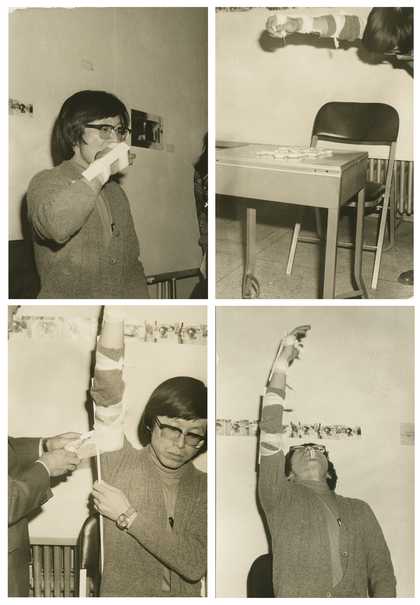

Fig.16

Lee Kun-yong

Eating Hardtack 1975

© Lee Kun-yong

Photo: Park Seobo

Lee himself described his performances as that which ‘happens when useless activity is pushed to its limit’.74 In many instances this meant stripping any practical use from otherwise functional actions. On such work, Eating Hardtack, was performed on 6 October 1975 in a small gallery of the National Museum of Contemporary Art. Photographs show the artist eating a type of hardtack (kanpan), a cheap and readily available snack food especially common in the Korean armed services, which were scattered on a plain wooden desktop (fig.16). During the performance Lee had an assistant wrap his right palm, his wrist and later is forearm in bandage-like white gauze. Tied to the gauze were thin, flat pieces of wood that acted like splints, diminishing his flexibility and thereby making the otherwise simple act of picking up a small biscuit and eating it extraordinarily difficult. As the performance progressed, the number of times Lee failed to put a biscuit into his mouth outnumbered his successes. Towards the conclusion of the performance Lee had his upper arm wrapped so that he eventually surrendered all flexibility. In order to pick up a biscuit he had to first stand up from his chair and bend his torso at the waist as if making a deep bow before picking up the hardtack, raising his arm and dropping it in his mouth.

The effort seems disproportionate to the reward, an allegory of the increasing number of encumbrances that during the mid-1970s conspired to make even the most basic and necessary actions required for everyday existence in Yushin Korea seem impossible. By having various limbs and body parts wrapped, Lee’s movements were reduced to a series of attenuated gestures. What the audience witnessed was not Lee eating, but him reproducing the act of eating.75 The focus was on the action. From the photographs that remain of the performance, it could be argued that the work made visible the effort that went into an activity so common as to be practically unnoticeable. That Lee’s hand, wrist, forearm and armpit were wrapped as though he was injured suggested that the act itself was painful.76 So palpable was this impression that it genuinely blurred the division between art from life, thereby making it more possible for intentionally artistic gestures to have an actual social and even political impact.

Context and class

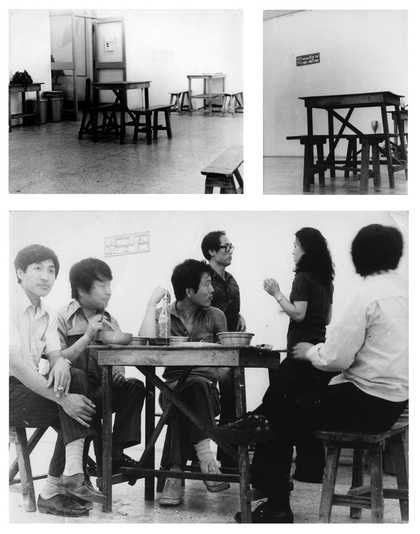

Fig.17

Lee Kang-so

Bar in a Gallery 1973

© Lee Kang-so

Perhaps the most provocative challenge to the separation of art and life was posed by Bar in a Gallery, a performance organised and conceived by Lee Kang-so in June 1973. Originally called Disappearance (Somyŏl), the event, which took place in the Myongdong Gallery in Anguk-dong, Seoul, lasted for almost a week.77 The gallery’s owner, Kim Mun-ho, was an early champion of experimental art, often inviting artists to exhibit their work there without charge.78 In a fairly large but indifferently lit space, Lee installed seven or eight wooden tables with accompanying chairs to create an interior resembling that of a café-restaurant. Brass kettles filled with makkŏlli, a Korean rice wine, sat on tabletops alongside dishes filled with typical bar snacks, their contents waiting to be emptied. In photographs of the event signs advertising common dishes like stir-fried squid and clam soup can be seen on the white walls (fig.17). Despite these notices, the tables and benches resembled freestanding dark wooden objects rather than functional pieces of furniture. Indeed, the critic Kim Su-hyun remarked that they looked like so many ‘readymades’.79

The scene changed when viewers entered the gallery and sat down at the tables. Some were students but most were adult men in casual and business dress. Many participants were artists personally acquainted with Lee but none of them were performers and they all appeared to chat freely. Were it not for the blank walls only occasionally enlivened by an incongruously small sign, the scene would pass for any other casual lunch in downtown Seoul. Having viewers participate in performances was not without precedent; in 1968 Jung Kangja invited audience members to attach balloons to her body.80 Yet Bar in a Gallery was the first performance to make audience participation absolutely central to its execution. Upon seeing the work, the dramaturge Oh Tae-suk declared theatre ‘dead’, a proclamation that acknowledged the dissolution of boundaries on which the idea of medium had for so long depended.81 Featuring a stage transformed into a bar and television studio, Oh’s own later ground-breaking play May, 1980 seemed to recuperate Bar in a Gallery as a way to think about life through the lens of art.

If performance was used to think more specifically about life in Yushin Korea, Bar in a Gallery was particularly effective at drawing attention to the relationship between performance and social class. Generally speaking, performance-based artworks became well known for their ability to draw large crowds, even to the point of obstructing nearby traffic.82 Attracting such a high number of attendees could itself be seen as a distinctly subversive act in light of state restrictions on any form of collective gathering. Such assemblies were also highly diverse in terms of age and occupation, and many audience members had no previous exposure to visual art, let alone performance. Bar in a Gallery was no different. Although taking place for only a week, it drew a remarkably diverse range of different people. The kinds of chairs and tables used, as well as their configuration recalled the chumak, the traditional pub-cum-inn that since the Koryŏ dynasty served as one of the few genuinely public places open to all regardless of class. A request for voluntary contributions was posted near the gallery entrance to help cover the cost of the wine and snacks, which Lee replenished daily, but the work was in fact free for all.83 Some viewers, however, were ‘befuddled’ by the situation and simply left without participating.84 For instance, Lee has recalled how students visiting the gallery ‘ran away, so [the critic] Yoo June-sang wrote a sign proclaiming that “this work is process art, thus viewers are meant to participate”.’85 The reluctance or confusion that some viewers expressed towards Lee’s bar reflected unseen divisions within what might otherwise be taken for granted as ‘the people’ or ‘the public’.

Lee stated that the idea for the work came from a meeting with an older friend at a makkŏlli tavern in his hometown of Taegu:

The traces of cigarette butts, dishes and cups on the tabletops made me almost feel the noise of the patrons who were there before me. I bought one of the chairs [from the tavern] and placed it in my studio. Then I bought all the chairs and tables and placed them in the studio, as well a large earthenware jar [changdok, made for storing fermented foods like soy or kimchi].86

Lee Kun-yong later described the tables and chairs as having all but ‘faded from the present era … the tables and chairs register as so much folklore’.87 Lee Kang-so himself commented that Bar in a Gallery was a gesture of recuperation: ‘the reason for calling it “disappearance” was because everything in the world disappears … when you have one drink, time evaporates so quickly … every idea and life changes moment by moment, appearing and disappearing’. 88 Lee actually used tables and chairs made from wooden boxes originally used by the U.S. military, the kind that would have been found in a chumak during the years immediately following the Korean War. Such furnishings, however, were anything but nostalgic. Even when seen in low-resolution black-and-white photographs, there is something concrete and immediate about the textures, sounds and look of the materials used. The wood from which the chairs were made looks too rough, the dishes too common, the signs too crudely painted to belong to the small group of self-styled ‘restaurants’ of 1970s Seoul. All belonged to more humble establishments serving a predominantly working-class clientele whose habits were distinctly at odds with the kind of haute bourgeoisie life widely promoted in lifestyle magazines.

But no matter how closely the work resembled a working class pub, its context within the four white walls of a gallery initially alienated some individuals for whom the idea of art may have been too closely entwined with the continued existence of a bourgeois elite. Visual art had long been allied to a particular class of urban sophisticates who often funded their activities through inherited wealth. The idea of art as being in part defined by its transcendence of the everyday was borne out by several artists. Performances could rely on everyday objects but not become equivalent to them. As Lee Kun-yong wrote in 1976: ‘I am not interested in bringing art to the level of the everyday’.89 Indeed, despite their almost categorical exclusion from mainstream histories of art at that time, Korean artists engaged with performance in the 1970s were among the most privileged of all cultural workers. Not only were they trained as visual artists, an education requiring a considerable amount of knowledge and social capital, but performance artists also relied on photography to make their works known to a larger audience, and cameras were still relatively expensive, as was developing film.

Performance artists were themselves ambivalent about the role of class in their own works. More than any other group of artists, they proactively sought to attract viewers from all walks of life, but especially from the newly emergent middle class. ‘The absorption of contemporary Korean art depends on increased interest from the ranks of the middle class’, argued Lee Kun-yong in 1977.90 Yet early definitions of performance art in Korea were inflected with a deep scepticism towards the pragmatic aspirations of the middle class. For example, in his essays on performance, Chang Suk-wŏn invoked the American critic Harold Rosenberg’s contempt for the middle class as the enemy of the avant-garde, and felt compelled to distinguish performance artists from bourgeois visual artists set on imposing their worldviews onto a passive audience.91

One the whole, performance artists recognised that they were no better than their audiences. By enacting ordinary daily tasks they challenged the exhortations of the state, which pushed its citizens to be better than they ever could be. Their works, in that they were about audiences watching individuals undertaking mundane activities, resonated with viewers accustomed to having their own quotidian routines monitored by the state. This may also serve to explain why performance artists attracted larger and far more diverse audiences than their peers working in other media.

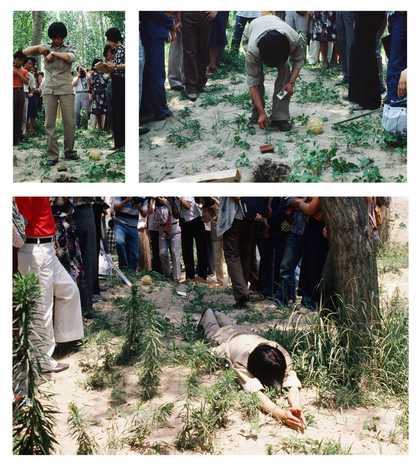

Fig.18

Lee Kun-yong

Relay Life 1979

© Lee Kun-yong

Photo: Kim Chang-sŏp

In lieu of a definite closing, let us turn to Relay Life, another work by Lee Kun-yong. It was premiered at the São Paulo Bienal in 1979, but its most compelling iteration may have been at that year’s Taegu Contemporary Art Festival. Relay Life illustrated what Lee’s good friend Kim Bok-young described that same year as the hallmark of an event: those who performed events did so not to create something but to arrive somewhere.92 The performance began with Lee systematically and deliberately laying his belongings on the ground, including his wallet, watch, shirt, pants, belt and shoes (fig.18). Eventually Lee himself dropped to the sand, utterly spent, his possessions strung out behind him. Taking the form of a self-inflicted strip search, the work represented a surrender of belongings and, according to Lee, ‘comes from the idea that a single individual’s life can be represented by his or her most everyday accessories’.93 The last image, in which he appears face down, encapsulates Lee’s ideas about the necessity of the unnecessary gesture, and seems to propose inaction as the most eloquent action of all.

The aesthetics of inaction presented in Relay Life reflected, at the end of 1979, what had become a paralysing impasse. For it was then that the Yushin era literally ended with a bang following the October assassination of Park Chung-hee. Lee’s prostrate form reflects the toll of what had been a long winter of authoritarian rule. But unlike the spent bodies of the Esprit Group or the unknown woman in the miniskirt frozen forever in 1973, Lee appears to be still breathing. Somewhere between taut and slack, his wiry body looks as if it may yet still rise. His prostrate form is not therefore one of finality; the accumulated violations of basic freedoms throughout the Yushin era made psychological closure impossible. Any pretence of objectivity was likewise doomed. But it was still possible to invoke the complex relationship between matter and action. For Lee and his comrades working with performance, realising this possibility was the only way to breathe during a period measured by an endless number of obligations and denials.