Sensationalist accounts of the origins of butoh performance and Viennese Actionism in much English language literature have hindered rigorous analysis of these artistic movements and have obscured serious discussion of the cross-cultural links that connected Japan and western Europe before and after the Second World War. This paper argues that the aesthetic and thematic parallels between these two performance-based art forms – characterised by violence, sacrifice and bodily mutilation – reflect the shared experience of war defeat and manifest an abject masculinity that follows in the tradition of Western avant-garde theatre set in motion by the work of French writers Jean Genet and Antonin Artaud. Indeed, Tatsumi Hijikata’s early butoh productions in Japan and the body art of Günter Brus and Rudolf Schwarzkogler in Austria can be said to have evolved from a shared history, one with roots firmly embedded in Western modernism.1

Central to this history are the patterns of intercultural exchange between Japan and the West that informed the evolution of avant-garde visual art and performance during the twentieth century. Western interest in Eastern visual culture at the turn of the century has been well documented and widely discussed. Japanese art, particularly textiles and woodblock prints, became extremely popular in nineteenth-century Europe, and Far Eastern artefacts proved a great influence on German expressionism. The Japanese dancer Michio Ito (1892–1961) garnered a significant following in the West, and returned to Japan with a new movement vocabulary, having studied at the Dalcroze Institute in Hellerau, Germany, before moving to the United States, where he taught at the Denishawn School of modern dance.2 Meanwhile, European avant-garde dance took on many Asian-inspired characteristics in its ambition to develop a new, anti-classical aesthetic. In her 1926 solo performance Witch Dance (Hexentanz II), for instance, the German dancer Mary Wigman wore a Noh theatre mask and Chinese brocade costume, and danced to a soundtrack of gongs and percussion instruments, which represented a dramatic departure from traditional Western stage dance. The European fascination with a newly ‘opened’ Japan, known as japonisme, also spread to the United States around the turn of the twentieth century, although American interest in the Far East began to wane in the run-up to the Second World War.

The reciprocal Eastern interest in aspects of Western modernist culture, however, has not been analysed in as much detail, despite playing a crucial role in the history of Japanese avant-garde culture in particular. For example, German Ausdruckstanz, or expressive dance, exerted considerable influence on the development of modern dance in Japan in the early twentieth century.3 European modern dance was exported by influential figures such as Baku Ishii, Takaya Eguchi and the composer Kosaku Yamada, who, having studied in Germany, introduced the eurhythmics method and the ‘free dance’ of Isadora Duncan to Ishii.4 Kazuo Ohno, who, along with Hijikata is recognised as one of the originators of butoh, undertook instruction from Eguchi, who was a pupil of Wigman’s in Dresden before the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1933 Ohno studied under Ishii, and the following year attended performances in Japan by the German dancer Harald Kreutzberg.5 Similarly, Hijikata claimed to have seen Ishii perform while he was still a schoolboy, and at the age of eighteen began studying at the studio of Katsuko Masumura, who had also studied under Eguchi.6 Thus, even a brief overview of the training of butoh’s first performers reveals the patterns of intercultural exchange between Japan and Europe prior to the war.

Yet, despite clear historical links between butoh and German Ausdruckstanz, there has been a tendency in critical writing to argue that butoh is uniquely Japanese in character. However, neither Ohno nor Hijikata trained in kabuki or Noh dance; in fact their formal training was almost exclusively based on Western dance techniques and it is known that Hijikata deeply admired the infamous Russian dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky.7 Dance historian Alix de Morant has identified strong stylistic similarities between Nijinsky’s 1912 ballet L’après-midi d’un faune (Afternoon of a Faun) and Hijikata’s A Tale of Smallpox (Hōsōtan) from 1972, drawing comparisons between ‘the animality of the body’ in both dances, as well as their use of contorted poses and an underlying eroticism of movement.8 De Morant extended this analysis by connecting Hijikata’s method with Wigman’s Ausdruckstanz, firmly establishing thematic and formal commonalities between avant-garde Western dance at the beginning of the twentieth century and post-war performance in Japan.9

Tatsumi Hijikata

Hijikata was born Kunio Yoneyama in 1928 in the rural, agricultural region of Akita in northern Japan. He saw Ohno dance for the first time in 1949, and relocated to Tokyo permanently three years later, where he began to dance at the Mitsuko Ando studio. To financially support his artistic career he took up a range of blue-collar jobs, but having come to the urban metropolis with a pronounced regional accent, Hijikata found himself an outcast, and took solace in literature. Among his favourite writers were the nineteenth-century French poets Arthur Rimbaud and Comte de Lautréamont, but above all he strongly identified with Jean Genet (1910–1986), in particular his criminality, his rejection of social norms, and his fascination with abjection.10 In these early years Hijikata used a range of different stage names, including Kunio Hijikata, Nero Hijikata, and Genet Hijikata. In 1958 he permanently adopted the name Tatsumi Hijikata.11

The movement technique that Hijikata developed, which he termed ankoku butō, featured the dancer in a hunched posture, firmly rooted to the ground, with knees swayed out sideways to create a bow-legged appearance. This distinctive form might be attributed to Hijikata’s obsession with the movements of polio victims, but also to the malnourished inhabitants of his home region, their legs deformed by rickets. In a personal essay penned in 1969, Hijikata wrote of an innate sense of envy towards those who have some kind of physical disability, noting that it constituted one’s ‘first step in butoh’.12 In this respect he channelled abject tendencies akin to those later outlined by the cultural critic Julia Kristeva, who, drawing upon psychoanalytic theory, argued in 1980 that the crippled body serves as a reminder of Otherness, but also of the fragile boundary separating the subject from disorder and primordial chaos caused by the breakdown of the distancing effect established in early childhood.13 Hijikata’s fascination with an ‘Other’ body type, particularly one exhibiting birth defects or the physical manifestation of illness, pervaded his choreographic aesthetic; indeed, he remained fascinated with death, deformity and decay throughout his career.14

The Korean Fluxus artist Nam June Paik, who lived and worked in Germany between 1956 and 1963, drew comparisons between Hijikata and the German artist Joseph Beuys, claiming that ‘both were unheimlich – inscrutable and scary’.15 It is certainly true that both artists possessed a talent for storytelling and self-promotion, with a tendency to stretch the truth to fit the mythical, occasional mystical personae they had created. Just as Beuys’s art is now intractably associated with his claim to have been nursed back to health by nomadic Tatars after being shot down over the Eastern Front during the Second World War, Hijikata rather controversially alleged to have become interested in German modern dance after watching Hitler Youth parades.16

Arresting though this statement may be, Hijikata’s influences were rather subtler than his deliberately inflammatory comments suggest. He derived inspiration from a blend of traditional Japanese and Western modernist sources, and was equally fascinated by contemporary Japanese art, such as the Hi Red Center group, as he was by the writings of Genet and the photography of German artist Hans Bellmer.17 In his controversial dance works, Hijikata sought to explore the theme of a new, transgressive masculinity, pushing his body to its physical limitations.

Forbidden Colours 1959

Forbidden Colours (Kinjiki) was the first full-length butoh piece to be performed on a Japanese stage. The title was taken directly from Yukio Mishima’s novel of the same name, although its content was more likely drawn from the writings of Genet.18 This piece remains notorious even in contemporary writing on butoh for its violent and sexualised content, yet it is documented only in a series of photographs and in the oral testimonies of Yoshito Ohno (son of Kazuo) and the dance critic Nario Goda. In his 2011 monograph on Hijikata, the cultural historian Bruce Baird sought to de-mythologise Forbidden Colours, and the narrative described here derives from Baird’s very detailed account, discrediting the oft-repeated falsehoods that have clouded discussion of this historically important work.

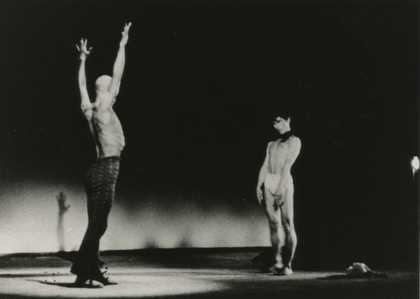

Fig.1

Tatsumi Hijikata and Yoshito Ohno

Forbidden Colours 1959

© Tatsumi Hijikata Collection, Keio University Archive, Tokyo

The first version of Forbidden Colours was premiered at the All Japan Dance Festival on 25 May 1959. The narrative centres on a young man (performed by Yoshito Ohno) who attempts to escape the advances of an older male figure (Hijikata). The scene opens to soft harmonica music, with the lighting focused on one corner of the bare stage; as a result, much of the action is obscured by darkness. Ohno appears helpless and despairing as Hijikata, his head shaved bald and his body covered in dark greasepaint, relentlessly pursues him (fig.1). Eventually, both find themselves centre stage, where Hijikata hands Ohno a live chicken. He forces Ohno onto the floor, where the boy catches the bird between his thighs and slowly suffocates it. Hijikata dances over Ohno’s body, after which he lays the chicken aside, and the men roll around the floor together, with, as Ohno claimed, ‘the intent to mime sodomy’.19 At this point, the lights are cut, and the stage is left in complete darkness. A recording of ragged breathing and scuffling plays over the speakers, with Hijikata repeatedly calling ‘Je t’aime’ (French for ‘I love you’). The piece ends in silence; when the house lights are turned up, one of the performers comes back onstage to remove the animal carcass.

Hijikata explicitly sought to shock with Forbidden Colours. His presence was powerful and hyper-masculine in comparison to Ohno’s passive, almost child-like demeanour. The most notorious element, however, remains the incident of animal slaughter; indeed, audience members were said to audibly groan when the chicken was being killed, and several walked out of the performance.20 Violence was both implied and enacted, as the chicken was killed before the two performers engaged in unseen but seemingly non-consensual intercourse. Accounts of this work have often reiterated myths that the chicken’s neck was broken, that it was used as a masturbatory accessory, or that the performers engaged in some kind of bestiality.21 The presence of the chicken was, however, highly significant. Its death immediately preceded the sexual encounter between the two men, suggesting that it functioned as a kind of totem (although, of course, the elision of homosexuality with violence and rape is deeply problematic). The chicken’s drawn-out sacrifice implies that the sexual encounter between these men could be read in two ways: either the young man was being paid for sex, or their coupling was part of a larger ritual, for instance, an initiation rite. The latter suggestion may explain the young man’s passive yet reluctant demeanour; eyewitnesses observed that he seemed to be ‘compelled’ by an unseen force. Hijikata’s evocation of sacrifice is reminiscent of the French surrealist Georges Bataille’s fascination with the subject, reinforcing the notion that the act itself confers sacred status upon the offering. The ritualised slaughter of the animal in this case suggests that the theatre in which the work is performed becomes a ceremonial space, and, through their engagement with the performance, that the audience is transformed into what the scholar Patrick ffrench has termed the ‘sacrificial community’.22

There is a clear and discernible narrative in this work, an organising structure that Hijikata completely abandoned in later works. Baird has claimed that the narrative element of this work and its highly expressionistic production represent strong parallels with Ausdruckstanz:

Certainly, if Hijikata had seen Wigman’s Hexentanz or Jooss’s Green Table, or even Graham’s Lamentation, he may have felt either scooped, or felt a deep resonance with what they were trying to do. Suffice to say, the connections with German Expressionist dance almost ensured both the narrative and mimetic quality of the dances as well as the emphasis on intense feeling and emotion.23

The second version of Forbidden Colours was performed on 5 September 1959 on a well-lit stage. This revised production featured a number of other performers and the narrative was divided into two separate scenes. The first act, ‘The Death of Divine’, was based on the protagonist of Genet’s 1943 novel Our Lady of the Flowers. The character of Divine, a transvestite prostitute, was performed by Kazuo Ohno, who was dressed in a tatty costume. Tormented by a group of men, Ohno’s Divine dies at the end of this act, recalling Genet’s words that, ‘slowly but surely I want to strip her of every vestige of happiness so as to make a saint of her’.24 In Genet’s novel, Divine becomes a victim of her circumstances, and is met with unimaginable cruelties at every turn. Yet the novel ultimately seeks to sanctify its characters on the basis of their transgressions and betrayals, and Genet used the death scene to demonstrate the beatification of Divine. That Hijikata elected to open his already controversial work with an explicit reference to Genet’s celebration of the abject demonstrated the importance of Western modernism and its most transgressive elements in the evolution of butoh.

The second act of this version largely took the same form as the original, though its narrative was more complex with the inclusion of other characters. Where the original Forbidden Colours was minimalist in style, the revised production featured more explicit violence, and displayed a clearer plotline. In the first version, the low lighting forced the audience to engage actively with the performance, as spectators had to strain to make out what was happening. In the second version, however, the sexual element was more overt. The victim was bound with ropes, and such openly fetishistic imagery reflected Hijikata’s burgeoning interest in conflating violence with eroticism, a feature that constituted an important part of the new post-war masculinity that forms the subject of this paper. In Hijikata’s second production of Forbidden Colours, two gay men are killed or sacrificed, and sexuality is amalgamated with images of violence, debasement and martyrdom. This fascination with marginalised sexuality and gender role-play was to become a recurring feature of Hijikata’s work, representing a deliberate attempt to confront conservative post-war Japanese society with an alternative masculinity, one that violently inverted expectations of virile sexuality.

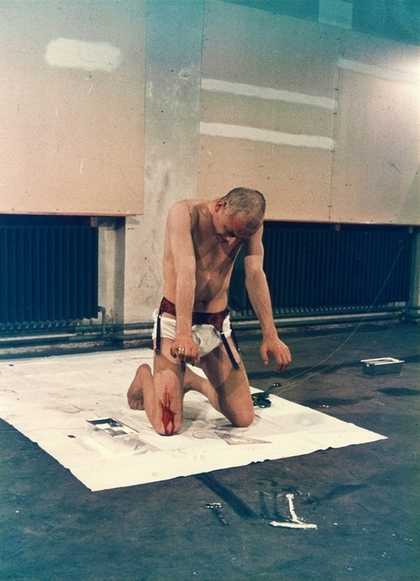

Tatsumi Hijikata and Japanese People: Rebellion of the Body 1968

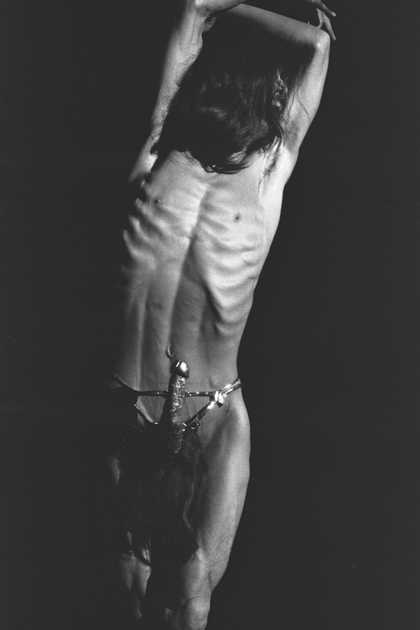

Fig.2

Tatsumi Hijikata

Tatsumi Hijikata and Japanese People: Rebellion of the Body 1968

© Tatsumi Hijikata Collection, Keio University Archive, Tokyo

Hijikata’s last solo performance – the title of which translates into English as Tatsumi Hijikata and Japanese People: Rebellion of the Body – was staged in October 1968 in the midst of major political upheaval and widespread student protests. As with Forbidden Colours, recorded evidence of this work is scarce; the full production would have run for approximately an hour and a half, but all that remains are a collection of photographs and twenty minutes of 8 mm film, which reveal the stage design to have consisted of large brass panels suspended in the air. The footage has no sound, although it is documented that the accompanying soundtrack consisted of piano music played live on stage and a recording of engine noises.

Rebellion of the Body opens with Hijikata carried on stage in a sedan, clad in an elaborate bridal kimono, and accompanied by several live animals in baskets. Reaching centre stage, he disrobes to reveal an emaciated, nearly naked frame, his genitals only partly covered by a large golden phallus (fig.2). In preparation for the premiere, Hijikata adhered to an extreme, ascetic lifestyle, restricting his diet obsessively and heavily tanning his skin. Grimacing at the audience, Hijikata repeatedly slams himself against the large brass panels lining the stage. Towards the end of this first act, he reveals a dead chicken hanging from the back of one of the panels. Lunging at the animal’s neck, he repeatedly thrusts the phallus against the panel in a frantic, failed attempt at intercourse. It is a surreal spectacle, followed by a series of costume changes for each subsequent scene. Similar to the myths associated with Forbidden Colours, the performance gave rise to various misconceptions; Bonnie Sue Stein, for example, asserted in 1986 that ‘in this performance Hijikata killed chickens’, although there is no evidence to suggest that he did anything of the kind.25

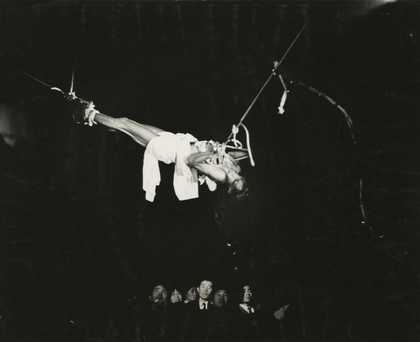

Fig.3

Tatsumi Hijikata

Tatsumi Hijikata and Japanese People: Rebellion of the Body 1968

© Tatsumi Hijikata Collection, Keio University Archive, Tokyo

In the next scene, Hijikata appears on stage in a satin evening gown and black rubber gloves, dancing in a pseudo-Spanish style, but as Baird points out, ‘there was also movement characteristic of the muscle atrophy and deformity of people who have polio or scoliosis’ (fig.3).26 Once again, Hijikata’s fascination with an ‘Other’ body informed his movement vocabulary, while the gloves conveyed something clinical and fetishistic. In the third section, he is dressed in a can-can skirt, twirling around the stage before removing the skirt and whipping it against the floor. The fourth act, ‘Hijikata as a Young Girl’, sees him clad once again in Japanese dress, this time a short kimono paired with knee-high sports socks, bouncing from one foot to the other. In the final movement, he is laid out on one of the brass panels and suspended above the audience, before being carried back to the stage, where he places a fish in his mouth and bows (fig.4).

Fig.4

Tatsumi Hijikata

Tatsumi Hijikata and Japanese People: Rebellion of the Body 1968

© Tatsumi Hijikata Collection, Keio University Archive, Tokyo

Numerous writers have claimed that this piece was a turning point for Hijikata, that it signalled the end of his interest in Western source material, and that it represented an attempt to immerse himself instead in the vocabulary of a new and uniquely Japanese counter-culture.27 However, the influence of figures including Genet, Artaud and Bellmer resonates throughout Hijikata’s career and is documented in his personal effects. Artaud’s The Theatre and its Double, first published in French in 1938, was translated into Japanese in 1965, and it is likely that Hijikata was aware of it through the writings of Tatsuhiko Shibusawa, a novelist and translator of French literature into Japanese. In addition, Hijikata’s scrapbooks relating to the development of Rebellion of the Body feature a number of images of Bellmer’s dolls, accompanying notes that focus on the fragmented body. Indeed, Hijikata’s preoccupation with Bellmer endured throughout his final choreographies, in which he called his trio of female dancers ‘the Bellemers’.28 Even the costumes in Rebellion of the Body reflect a fusion of traditional Japanese design and Western fashion, reflecting Hijikata’s desire to conflate the European modernism that had had such a crucial impact on his work with traditional Japanese culture.

In both Forbidden Colours and Rebellion of the Body, Hijikata – alternately clothed in drag or fully exposed to the audience – is symbolically castrated by his desperate attempts at penetration, whether with an unwilling male partner or an unforgiving brass panel. In the last act of his 1968 performance he presents his abused body as a sacrificial offering to the audience, reflecting the Christian notion of sacrifice as a means of salvation. This grotesque choreography has been contextualised with reference to the Second World War and the aftermath of the atomic bombings in Japan. The butoh practitioner and historian Sondra Fraleigh, for example, has asserted that, like the younger German choreographer Pina Bausch, Hijikata was ‘responding to the graveyards and ruins of World War II’.29 The personal effects of the war on Hijikata cannot be underestimated – he claimed that three of his older brothers were killed in action – but his sexualised, abject performances, like those of Brus and Schwarzkogler discussed later, seem to express a more complex attitude towards the emasculating experience of defeat and capitulation.

Cultural crises

The aftermath of the Second World War in Japan brought with it the terrible fall-out of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, occupation by foreign forces, the demobilisation of the army, and the surrender of the emperor, all of which drastically shaped Japan’s visual culture during the post-war period. Drama historian Carol Martin has also argued that the 1960 security treaty between the USA and Japan (known as ANPO) played a major role in shaping the evolution and environment of experimental theatre in the country, for the subsequent influence of Western theatre on Japanese performance caused a number of practitioners to turn their backs on shingeki (new theatre), a form that has been described by the playwright Takeshi Kawamura as ‘emblematic of Japanese self-hatred’.30 Instead, artists embraced alternative formats such as butoh in the hope that they represented a uniquely Japanese sensibility. However, the forces that shaped post-war Japanese society arguably gave rise to a dual cultural identity, which art forms like butoh reflected. As scholar Daisuke Nishihara has observed, ‘Japan has characteristics of both the Orient and the Occident. This is the reality of modern Japanese history’.31 It was into a deeply troubled culture that butoh was born, and accordingly, it is not surprising that Hijikata spoke of the significance of ‘crisis’ in his dance: ‘When Mr Mishima Yukio saw my work, his first impression was just that – a sense of crisis. I demand a sense of crisis. I am not being visited by a sense of crisis, rather I am demanding it.’32

In the decades following the Second World War, avant-garde theatre sought in its own way to heal some of the wounds of the recent past. For many Japanese theatre-makers there was a strong desire to break away from increasing Western influence, yet this was countered by an equally vociferous resistance to established cultural traditions. The situation mirrored that facing German and Austrian artists in the same period. The collective anger of a younger generation was directed at the so-called Tätergeneration (the ‘generation of perpetrators’), and the art that emerged was designed to break away from the pre-war lineage.

However, the Austrian context was very distinct from that of post-war Germany. According to the ‘occupation doctrine’ drawn up at the end of the war, Austria was a victim of German occupation from 1938 until 1945, and thus could not be held responsible for Nazi crimes. This statement, enshrined in law, helped to cement the notion of Austrian victimhood. However, there is a clear disjuncture between this narrative, in which Austrians were the first victims of Nazism, and the reality in which Viennese crowds warmly welcomed Hitler’s arrival.33 Furthermore, the notion of forcible and unwelcome occupation is contradicted by the result of the Volksabstimmung (referendum) held on 10 April 1938, in which 99.7% of the population apparently voted in favour of joining ‘Greater Germany’. Nonetheless, the dominant ideology in post-war Austria held that the nation had been annexed in a similarly violent manner to Poland; a national government decree in 1945 proclaimed that, ‘our home country, the first victim of Fascist imperialism, is again free and independent’.34

As swathes of pre-war avant-garde art had been condemned as ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis and destroyed during the years of occupation, the post-war art scene in Austria looked back to a past ‘Golden Age’ for inspiration, as though recuperating what had been lost. Reacting violently against this was the work of a small group of individuals who came to be known as the Actionists. Viennese Actionism is a retrospective term that has come to characterise the productions of a loose collective, whose performative work involved the extreme use of the body and its excretions, including blood, urine and excrement.35 The four central figures involved in this grouping – Günter Brus, Otto Muehl, Hermann Nitsch and Rudolf Schwarzkogler – while markedly distinct from one another in terms of their aesthetic style, had in common highly personal connections to the Second World War: Brus’s father retained powerful sympathies for fascism, Muehl had served in the German Wehrmacht, Nitsch had lived through the firebombing of Vienna, and Schwarzkogler’s father had been gravely injured at Stalingrad.36

The brutal nature of actionist art reflected the group’s response to the social, political and psychic conditions that characterised post-war Austria, including the notion of victimhood and the powerful influence that Catholicism exerted over the nation. Brus and Muehl coined the expression ‘direct art’ as an alternative to the American artist Allan Kaprow’s term ‘happening’, while actionist events went to greater extremes than Fluxus happenings.37 Actionism also represented an absolute break from the stifling nature of state-sponsored art, as Muehl’s 1970 manifesto illustrated:

we feel and sadly I am forced to see, that precisely these people who make Happening and Fluxus are the ones who collaborate with the state, and respond to its manipulations and are simply idiots creating entertainment. And view themselves vainly as revolutionary or as the so-called shitty avant-gardists.38

The group’s visceral work sought to shock conservative Austrian society, and contemporary newspaper reports paint an image of hysterical audience reactions, spectators storming out in protest or fainting in response to the violent and sexual acts being presented. A 1966 review in Time magazine of the Destruction in Art symposium refers to ‘four Viennese men from something called the Institute for Direct Art’ who ‘held an audience of 100 spellbound’. The review concludes with the wry observation that the London Times art critic, on viewing the actions, was ‘trying very hard to be broad-minded about it all’.39

Günter Brus

Brus was born in the Styrian town of Ardning in 1938, and moved to Vienna in 1957 to study graphic art at the Akademie für Angewandte Kunst. His education was interrupted by a period of military service, after which he found himself unable to continue painting in a classical style. Brus was captivated by the work of the Austrian expressionists, in particular that of Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, although he was largely unmoved by contemporary Austrian painters. In the late 1950s he became acquainted with Alfons Schilling, who considerably influenced Brus’s approach to painting, and in 1960 met Otto Muehl before taking part alongside Nitsch and Schilling in the Spirit and Form exhibition in Vienna in 1961. An interest in abstract expressionism led him to focus more on the act of painting than the end product (see Untitled 1960, Tate T04927), but by 1964 Brus had largely abandoned the canvas and began choreographing performances. His first action, Ana 1964, was designed for film according to a score prepared in advance. However, he was dissatisfied with the result and began to devise a type of actionism for photography instead.40

Brus was a vocal critic of Austrian society and of the dominant understanding of its fascist past. In such a deeply conservative environment, there was a widespread reluctance to revisit recent history, let alone to put itself through the intense process of de-nazification, as had occurred in Germany. Brus viewed Austria’s official victim narrative with profound scepticism:

I saw Austria as a sort of saucepan in which brown soup had been cooking and which people had managed to scrub spotlessly clean, but where they had missed the dirty marks around the edge of the lid. Austria not only gave rise to the pan-smith of National Socialism, but also put the lid on its creation.41

As in Hijikata’s butoh, the artist’s body was central to Brus’s actions, and over a five-year period he made progressively more intense pieces that took him to his physical limits. At the University of Vienna’s ‘Art and Revolution’ event in 1968 Brus’s performance involved him stripping off his clothes, cutting himself with a razor blade, drinking his own urine, covering himself in excrement and, as a grand finale, masturbating while singing the Austrian national anthem. He was given a six-month prison sentence as a result of his ‘vilification of Austrian national symbols’, and in 1969 fled to Berlin to escape the charges.42

Art historian Gerald Schröder has drawn parallels between Brus and the art brut painter Jean Dubuffet in terms of their interest in madness and perversion.43 Brus’s artistic trajectory shifted dramatically from action painting to extreme performances. Underlying these works is a desire to merge the canvas with the body; in his Self-Painting - Self-Mutilation series, Brus’s body became the canvas, while in his later performances he literally opened the body to confront the audience with the abject nature of what lies beneath its surface.

Vienna Walk and Self-Painting – Self-Mutilation 1965

Fig.5

Günter Brus

Vienna Walk 1965

Courtesy the artist and Roman Grabner, BRUSEUM, Graz

Photo: Ludwig Hoffenreich, Fotoatelier Laut, Vienna

On 5 July 1965 Brus undertook his first public actionist performance, Vienna Walk (Wiener Spaziergang), which was documented by the photographer Ludwig Hoffenreich and filmed by Muehl and Schwarzkogler. For this event, which Brus termed ‘a living picture’, he was clothed in a formal suit and covered from head to toe in white paint, with a black line running down the centre of his body (fig.5). The action was intended to comprise a structured walk through the city, stopping at specific landsmarks, beginning in Heldenplatz and proceeding to Stephansplatz. The first location carried political significance for it was where large crowds warmly received Hitler in 1938 following the annexation of Austria. However, after only twenty minutes Brus was stopped by the police, charged with causing a public disturbance, and ordered to pay a fine of eighty schillings before being sent home in a taxi.44

As is typical of actionism more broadly, the legends that have evolved around this work have overshadowed critical writing, and have obscured more nuanced readings of its underlying themes. Art historian Mechtild Widrich has observed that Hoffenreich’s most well known images of the work illustrate the encounter with the police, which has accordingly been understood as an integral element of the performance.45 Hoffenreich’s photographs mediate between the audience and the action in a way that positions Hoffenreich somewhere between the roles of photographer and director. However, as Widrich noted, the images do not provide a clear-cut account of what exactly took place.46 For example, while it is often repeated that Brus was arrested, there is no clear evidence of this from the series of photographs. In addition, Brus signed the backs of the photographs, blurring the boundary between their status as documents of an action and their status as readymade objects.

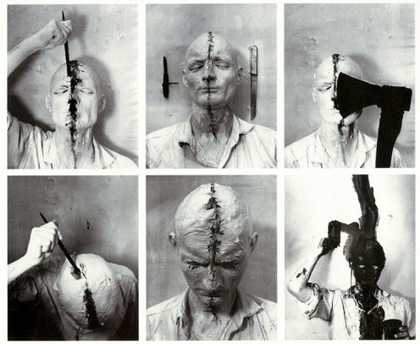

Fig.6

Günter Brus

Self-Painting 1964

Courtesy the artist and Roman Grabner, BRUSEUM, Graz

Photo: Ludwig Hoffenreich

The following day Brus performed another action, Self-Painting – Self-Mutilation (Selbstbemalung – Selbstverstümmelung), in front of an invited audience, shifting focus from an outdoor setting to a private, contained environment. The action was based on two series of photographs completed earlier that year, titled Self-Painting and Self-Mutilation respectively. The first of these, also taken by Hoffenreich, documents an action by Brus, painted completely white, set against a plain white wall in a basement studio known as the Perinetkeller, which the Actionist circle shared among them. In Hoffenreich’s photographs Brus can be seen hammering nails in between his fingers, and later with various cutting instruments – including scissors, a saw, a corkscrew and a knife – positioned next to his head. Towards the end of the action Brus painted a black line down the centre of his face and neck and posed for the camera with an axe, before continuing to add more black paint in thick layers until his facial features became totally obscured (fig.6). The Self-Mutilation photographs are more voyeuristic than the Self-Painting images, and the narrative they convey is darker. In this series Brus can be seen occupying the space with metal hooks, a tangle of wires and large amounts of paint, as well as a pair of disembodied plaster feet. In one photograph he appears to be drawing hair-like black wires out of his mouth, a disturbing allusion to the piles of human remains discovered in Nazi death camps at the end of the war. Brus combined elements of these two earlier actions into the live staging in 1965, merging the titles of both to demonstrate the continuation of several important underlying themes, including and especially the mutilation and obliteration of the artist’s body (figs.7 and 8).

Fig.7

Günter Brus

Self-Painting – Self-Mutilation 1965

Courtesy the artist and Roman Grabner, BRUSEUM, Graz

Photo: Ludwig Hoffenreich

Fig.8

Günter Brus

Self-Painting – Self-Mutilation 1965

Courtesy the artist and Roman Grabner, BRUSEUM, Graz

Photo: Ludwig Hoffenreich

On a formal, aesthetic level Vienna Walk and Self-Painting – Self-Mutilation are very similar, with Brus covered in white paint and ‘cut’ in half by a thick black line. Both works also allude to the idea of a divided body, a body that constitutes the instrument and the site of the action, the model and the central focus. This idea of division can equally be read as a splitting of the self, or as a gaping wound, one that was put on very public show in the centre of Vienna, tracing a link to the Anschluss. The titles of these actions are also significant: Vienna Walk implies a touristic outing around city, but in reality its highly charged choice of location and route drew an immediate and visceral connection to the horrors of the recent past. Self-Painting – Self-Mutilation demonstrates a radical development of concept of the body-as-canvas, shifting from the relatively harmless ‘self-painting’ to the more extreme ‘self-mutilation’. Both actions also create the impression that Brus’s body has become fragmented, and has almost disappeared. Schröder has compared Brus’s visage to a death mask,47 while the use of white paint has symbolic significance, implying a form of cleansing or purgation, and could be read as indicative of a desire to renounce painting.48 All of these challenging, confrontational ideals were to be taken forward by Brus in the years to come, reaching extreme conclusions in his Endurance Test.

Endurance Test 1970

Fig.9

Günter Brus

Endurance Test 1970

Courtesy the artist and Roman Grabner, BRUSEUM, Graz

Photo: Klaus Eschen

Fig.10

Günter Brus

Endurance Test 1970

Courtesy the artist and Roman Grabner, BRUSEUM, Graz

Photo: Klaus Eschen

Performed on 19 June 1970 at Aktionsraum 1 in Munich, Endurance Test (Zerreißprobe) was Brus’s final and most extreme action, and remains notorious for its sequences of self-mutilation. Unlike his other filmed actions, Endurance Test was recorded in a straight, documentary style. In the film Brus presents himself to the audience in white underwear, black stockings and a garter belt, having shaved his head completely bald, and stands on a square of white fabric. The audience is located extremely close to Brus throughout, seated at a distance where they could easily reach out and touch him, or vice versa. The performance begins with Brus urinating into a glass, before swallowing the contents. Using a razor blade, he slowly cuts the flesh on the back of his head, turning to the audience to reveal the trails of blood (figs.8 and 9). Throughout, he exhibits a desire to make his suffering visible, as if to prove that the actions are real, in contrast to the symbolic ‘cutting’ seen in previous works. Clearly in pain, Brus prostrates himself on the floor like a broken doll before regrouping himself, and in a calm and precise manner begins the process of making incisions in his skin once more. His is not the wild, orgiastic action of Hermann Nitsch or Otto Muehl, but a ritualistic procedure, almost surgical in its execution. The pace increases as Brus reaches his denouement, alternately laughing and whimpering as he throws himself around the space, before huddling into a foetal position on the floor. The piece ends abruptly, with Brus simply standing up and exiting the stage space.

Despite its extremity, Endurance Test is almost meditative in its quieter moments, and Brus’s actions were carefully considered and strictly choreographed throughout. It is clear that no part of this work was improvised – Brus composed a score for the action and provided a programme for the audience. During this ritual of self-flagellation, Brus interrupted his own contemplative state, screaming and throwing himself across the room as if possessed. He methodically cut through his clothing, which progressed to cutting through his own flesh. Indeed, Brus became increasingly vulnerable as the piece advanced, performing private functions before the audience, stripping naked, and bleeding from his various wounds. Here, the ‘cut’ that was implied by the painted black line in his earlier Self-Painting – Self-Mutilation was made flesh with the use of a razor blade. Like Hijikata in Rebellion of the Body, Brus offered his body to the audience in a way that evoked the broken, bleeding body of Christ that would have formed a central role in his Catholic upbringing. Moving on from the theological concerns of Catholic imagery, Brus’s work served as a corporal response to a sense of abandonment observed at the beginning of his career: ‘this country had been abandoned, not by a Catholic god, however, but by the rest of the world’.49

Brus’s choice of costume for this performance is highly significant. Clad only in women’s underwear, in particular the fetishistic totems of stockings and suspenders, he flirted with elements of drag performance. These inherently feminine markers of eroticism have clear sexual connotations, but Brus simply cut through them before slicing into his own skin. As in Hijikata’s early work, eroticism and violence were here conflated by Brus. However, while Hijikata directed his violence at a younger male victim, Brus inflicted it upon himself, turning it into a public spectacle. As he threw himself across the stage, he gave the rather desperate impression of pleading for help, before turning back and self-harming again. In Rebellion of the Body cross-dressing was invoked by a heterosexual artist and served to challenge the accepted norms of masculinity. Brus undermined these conventions even further with his indulgent display of vulnerability, conflating once again queer sexuality with pain and violence.

It seems significant that Artaud’s seminal work The Theatre and its Double (and in it his essay on the ‘theatre of cruelty’) was published in German one year before Brus’s Endurance Test. With this work Brus also extended the legacy of Genet in his aestheticisation of suffering and sado-masochism; in his part-autobiographical novel The Thief’s Journal (1949) Genet recounts how he sought to achieve sainthood by embracing the abject, while in Brus’s performance sado-masochism is used to achieve some sense of relief from a state of crisis, to transcend the physical and transgress social and cultural norms. The sadomasochism and suffering of the artist was not performed but was real, echoing both the redemptive power of Catholicism (through the medium of Jesus’s suffering) and Genet’s violent sanctification of Divine. Yet it also can be said to have reflected Austrian politics, and the self-flagellation associated with notions of guilt and victimhood.

Rudolf Schwarzkogler

While Brus explored the politics of the body in a visceral way within a real, live context, Rudolf Schwarzkogler adopted a different approach that attempted to heal some of the wounds Brus opened to the public. Schwarzkogler, who was more introverted in character, remained a somewhat marginalised member of the Actionist circle and has often been excluded from the more sensationalist accounts of the group’s work; certainly his actions display little of the Dionysian spectacle associated with Muehl and Nitsch. Art historian Eva Badura-Triske has noted that he ‘shared the artistic concerns of Brus, Muehl and Nitsch in principle, but his cooly-distant, restraint [sic], even calculatingly constructed approach marked an antithesis to the activities of his fellow Actionists’.50 Similarly, Konrad Oberhuber has called Schwarzkogler ‘the mystic of the group’.51

Schwarzkogler was born in Vienna in 1940, the son of a doctor and a beautician. Three years later his father shot himself after losing both legs at Stalingrad. He studied commercial art at the Höhere Graphische Lehr-und Versuchsansalt in Vienna, where he befriended Heinz Cibulka, who was to model for Schwarzkogler in a number of his actions. While studying, Schwarzkogler also became acquainted with Nitsch, and, despite their markedly different approaches to actionism, the two became close friends. Like Brus, they shared a deep interest in Austrian expressionism, in particular the work of Gustav Klimt, Schiele and Kokoschka. Schwarzkogler was intensely cerebral, and was particularly knowledgeable in the fields of music and philosophy.

He destroyed a significant amount of his early artwork, although one significant piece remains from 1962, in which he covered the figure of Christ removed from a wooden crucifix with blue paint. The colour held particular significance for Schwarzkogler, who developed a fascination with Yves Klein around this time, while Nitsch recalled that he expressed a desire to paint forests and landscapes blue: ‘it was the color to which he felt attracted … In his eyes it embodied the refinement and transformation of the instinctual into the Apollinian way of life’.52 This untitled work represented his major shift in Schwarzkogler’s work from panel painting to a subtle form action painting, while the choice of subject serves as a striking reminder of the significance of Catholicism in the work of the Actionist circle. Like Nitsch’s mutilated lambs, the desecration of the crucifix here challenged the sanctity of the Catholic church in Austria, and was a provocative, if discreet gesture.

Schwarzkogler produced a total of six actions in a period lasting just over one year, only one of which, Wedding 1965, was performed before an invited audience. None of these were filmed in their entirety, with the exception of his 4th Action, which was documented by Brus. However, the photographs of Schwarzkogler’s actions – which were performed in a distinctive setting, usually a sterile, white room – were never publicly exhibited during his lifetime. Dead animals, including fish and chickens, and medical instruments, which on occasion evoke methods of torture, feature regularly in his work. On the occasions that Schwarzkogler modelled for his own actions, he would either be dressed in white or would appear naked, adopting the role of a ritualistic leader or priest. In her essay on abjection, Kristeva acknowledged the necessity for ‘purifying the abject’, which is inherent to religious traditions, and in these works it can be argued that Schwarzkogler conflated Catholic imagery with scenes of abjection in a complex attempt to atone for the sins of the recent past.53

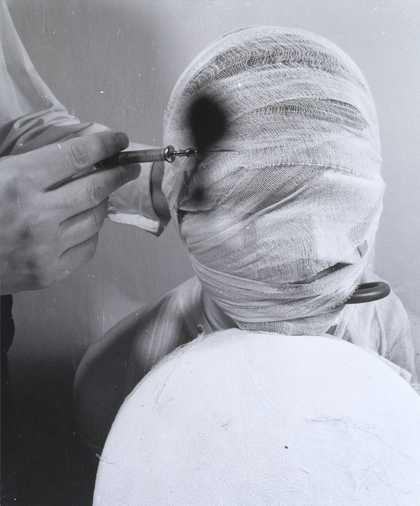

2nd Action / 3rd Action 1965

In addition to the legends that surround Schwarzkogler’s personal life, there is a degree of confusion in the literature on actionism regarding the documentation of the artist’s second and third actions.54 Both were staged in Cibulka’s apartment and documented by Hoffenreich. The second, third and fourth actions followed in quick succession and featured not only many of the same props and implements but addressed similar overarching themes. The following analysis of Schwarzkogler’s work considers the third action as a logical continuation of the second, although it should be noted that the actions were in fact separate pieces.

These actions focus on two figures. Schwarzkogler appears in the guise of a doctor tending to a bandaged male body, who can be seen in the images in various positions lying on a gurney, sitting upright in front of the camera with dead fish taped to his body, and attended to by the hands of the doctor figure, whose face is never seen. The unidentified body is subjected to the humiliating scrutiny of the audience, his vulnerability underscored by the cold, clinical setting and the manner in which he has been prostrated, only partly clothed.

Fig.11

Rudolf Schwarzkogler

2nd Action 1965

© The estate of Rudolf Schwarzkogler, courtesy Galerie Krinzinger, Vienna

Photo: Ludwig Hoffenreich

The precise role of the doctor, or at the very least the figure in control, is ambiguous. His clothing is formal – glimpses of his body reveal that he is wearing a smart suit and a shirt – and while he tends to the patient, he also seems to be inflicting harm. Medical instruments are replaced with torture devices; in one image from the second action the patient’s head is fully wrapped in bandages and the doctor appears to be inserting a wire into the young man’s eye (fig.11). In another from the same action, the wire is replaced with a corkscrew, while a dark stain suggestive of blood spreads across the bandage. In a clumsy and rather ineffective manner, Schwarzkogler assumes a role somewhere between a torturer and a healer. It is significant that Schwarzkogler’s father, a man absent for most of the artist’s life and who died in horrific, violent circumstances, was also a doctor. In fact it could be argued that in this work Schwarzkogler sought to reimagine his missing father, and convey the violence of his death and subsequent absence.55

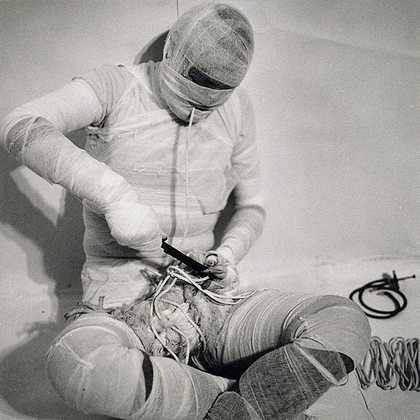

Fig.12

Rudolf Schwarzkogler

3rd Action 1965, printed early 1970s

© The estate of Rudolf Schwarzkogler, courtesy Gallery Krinzinger

The brutalisation of the male body was clearly of central importance to these actions. A close-up photograph taken during the second action depicts the young man’s crotch soaked in dark liquid, with a piece of eviscerated meat where his penis should be. Above him looms the hand of the doctor, holding a syringe. The third action clearly continued this narrative, for the young man is depicted in one photograph laid out on a hospital trolley, his penis now bandaged (fig.12). In every image, the bodies of In every image, the bodies of the ‘doctor’ and the ‘patient’ appear only as fragments. Like the Acéphale, Bataille’s sacred monster, the doctor figure is generally pictured headless. Indeed the theme of disembodiment runs throughout Schwarzkogler’s second and third actions and, as in Brus’s ‘self-painting’ experiments, the (male) body is used as a canvas on which to create these surreal tableaux vivants. At the same time, however, the continuing fragmentation of the male figure implies a kind of dismemberment, recalling once again the mutilation of Schwarzkogler’s father before his death at Stalingrad.

The visceral nature of some of these images, however, has led to the perpetuation of several myths regarding Schwarzkogler’s practice. One persistent accusation maintains that, in the course of one of his actions, the artist cut off his own penis, an inaccuracy that was propagated in a Newsweek interview with the American performance artist Chris Burden.56 As Susan Jarosi has remarked, however, such rumours are extremely detrimental to contemporary analyses of these artworks, as they conflate artistic practice with a genuine interest in sado-masochism, when there is no evidence to indicate that Brus or Schwarzkogler engaged in such practices outside of their actionist works:

A more serious and pernicious consequence of this kind of elision is that it reinforces spurious assertions regarding purported masochistic practices in Viennese Actionism: perhaps most notoriously that Rudolf Schwarzkogler ‘performed’ successive acts of self-castration that resulted in his death, when in fact his actions of the mid-1960s utilized the model Heinz Cibulka to create tableau of a wounded male body.57

Jarosi’s use of the term ‘tableau’ is key: in these performances staged for the camera Schwarzkogler sought to portray damaged masculinity without going as far as some commentators have believed. While the theme of castration anxiety was explored in more explicit terms in his second and third actions, his final piece sought to heal some of the wounds exposed in his earlier works.58

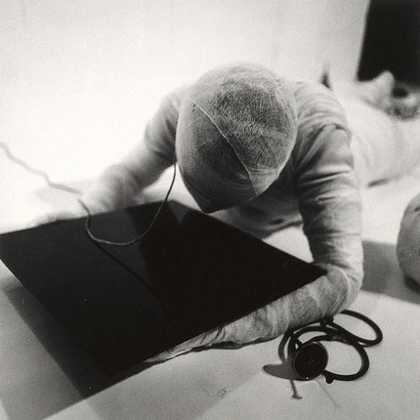

6th Action 1966

Fig.13

Rudolf Schwarzkogler

6th Action 1966

© The estate of Rudolf Schwarzkogler, courtesy Galerie Krinzinger, Vienna

Photo: Michael Epp

Schwarzkogler’s sixth and last action took place in the artist’s apartment, and was documented by the photographer Michael Epp. Like his earlier works staged for the camera, this action can be understood as an intimate collaboration between the performer and the photographer. As with his second and third actions, this work once again featured a bandaged male body, although in this case Schwarzkogler himself adopted the role of the ‘patient’ and was completely swathed in white medical dressings (fig.13).

Fig.14

Rudolf Schwarzkogler

6th Action 1966

© The estate of Rudolf Schwarzkogler, courtesy Galerie Krinzinger, Vienna

Photo: Michael Epp

Fig.15

Rudolf Schwarzkogler

6th Action 1966

© The estate of Rudolf Schwarzkogler, courtesy Galerie Krinzinger, Vienna

Photo: Michael Epp

Although littered with various objects – including medical implements, tangled wires, a pane of glass painted black and a dead chicken – the space in which 6th Action was performed was significantly less cluttered than in earlier pieces. Indeed the room was completely white and sparsely furnished. In the series of photographs that document this work, Schwarzkogler is seen illuminating the dead chicken with a bare bulb, cutting up wires nestling in his crotch (fig.14), using a stethoscope to listen to a white plaster ball (many of the items in this work are re-employed from earlier actions), and staring into the pane of black glass as if it were a mirror (fig.15). His poses are quite contorted in some of the images and, unlike in the second and third actions, his whole body is often visible. Whereas the shots of previous actions appear to have been very staged and the gestures sedentary, there is a greater sense of movement in this piece, and the implied violence of previous actions is replaced by a desire for healing and reconstruction. The resulting effect is less collage-like than the photographic series of earlier actions, and is more cohesive in form and structure.

Schwarzkogler was an avid reader of Artaud, but by 1966 he had begun to turn towards Eastern philosophies for inspiration; he was fascinated by the principles of yoga, and in particular the idea of physical discipline as a route to enlightenment. He even adopted ascetic fasting rituals similar to those undertaken by Hijikata before Rebellion of the Body. Badura-Triska has stated that Schwarzkogler also employed the yogic method of abdominal breathing and aspects of tantra where, ‘rather than abstinence, followers adopt a ritualized or sacrilized form of dealing with physical experiences’.59

The 6th Action departs significantly from the bloody aesthetic of his earlier actions and those of his fellow Actionists. Where Brus sought to elicit an intense response from his audience, Schwarzkogler avoided public display, choosing instead to conduct his actions in private. In 6th Action he looked inwardly, performing a trance-like ritual in an otherworldly setting that elided the sites of trauma and healing. Rather than animating and exalting the damaged body as Brus and Hijikata did, Schwarzkogler wrapped the broken body in bandages and reconstructed it with various instruments, wires and symbolic totems as though attempting to bind and contain the suffering of recent history.

Transgression, sanctification, purification

Analysis of the works of Tatsumi Hijikata, Günter Brus and Rudolf Schwarzkogler is only possible by means of fragmentary documentation or second-hand accounts from bemused spectators. Retrospective examination of early butoh and actionist performances is therefore fraught with difficulty, and the relative status given to the documentation inevitably determines the way in which the works are interpreted and understood. Myths also continue to dominate English language literature on each of these figures; as well as those attached to Brus and Schwarzkogler, Hijikata’s brushes with the law, for instance, have become standard elements of his biography. Certain factors are indisputable, however, and this article has sought to challenge pre-conceived notions about the cultural isolation of these works, and also to debunk the mythical aspects of their controversial nature. It is clear that thematic, aesthetic and historical intercultural links connect these seemingly disparate movements, two of the most crucial being the relationship with Western modernism, and the artists’ shared fascination with the fragmented or deformed male body following the Second World War.

A clear line of influence stretches across European and Japanese cultural borders. Hijikata’s butoh was an art form deeply concerned with loss, one that embodied an alternative masculinity that stood in stark contrast to the heroic male archetype. The effects of post-war trauma and the emasculation of defeat were etched across the bodies of butoh performers, but were equally embodied in the confrontational works of the Viennese Actionists. The purgation of memory played out in these visceral, performative works, forcing the audience to look upon the body as a site of ritual sacrifice, sado-masochistic manipulation and, ultimately, spiritual sanctification. The past was continually revisited during this period, and the artist’s body became the central focus, as historian Sebastian Conrad has observed:

In the cases of post-war Germany and Japan, the past and the present are severed through historical ruptures and ‘zero hours’ which, it is held, need to be bridged in order to come to terms with a traumatic experience that haunts both societies. From this perspective, memory appears as the almost direct expression of a national mentality, indicative of a nation’s ability to mourn, to learn and to mature (by overcoming narrow nationalist perspectives).60

In these diverse, multisensory pieces, the gap between audience and performer became increasingly narrow. The spectator was expected to ‘work’ as part of each action, whether straining to see the scenario played out on Hijikata’s stage, or piecing together the narrative of Schwarzkogler’s series of eerie photographs. Accordingly, the action could not and cannot function without an audience. This idea of confrontation between artist and audience is prevalent in the writings of Artaud. In an essay titled ‘No More Masterpieces’ Artaud proposed ‘a theatre where violent physical images pulverise, mesmerise the audience’s sensibilities, caught in the drama as if in a vortex of higher forces’.61 However, the critic Maggie Nelson has observed that, while Artaud’s concepts have not been applied successfully to theatre, they have had a great bearing on what she calls ‘more experiential, physically immediate spheres of expression’, including butoh.62

Hijikata, Brus and Schwarzkogler prepared their bodies in a ritualised way before or during their performances, often altering their physical appearance as a result, from shaving their heads and sculpting their bodies to mutilating their flesh in both literal and figurative ways. A deep, underlying interest in ritualism and the notion of sacrifice pervades Hijikata’s early butoh performances and Brus’s and Schwarzkogler’s actions. Hijikata starved himself, covered his body in greasepaint, incorporated multiple complex costume changes in each performance, and took himself and his dancers to their physical limits with his unusual chorography. Brus sought to take his body to extreme levels of suffering and pain in his aestheticisation of suffering and sado-masochism, while Schwarzkogler’s approach was rather more subtle, serving to heal the body and spirit as part of an atonement ritual. Facing the legacy of war defeat, these artists explored different facets of the fractured male ego and the castrated post-war body in their works throughout the 1960s, challenging their audiences to keep looking, and forcing them to accept some form of complicity.

The conflation of violence and eroticism is a constant feature that connects the first butoh performances with Viennese Actionism, a tendency that relates directly to the writings of Genet. These artists maintained a profound interest in the notion of sacrifice and the use of symbolic totems, and in the wake of war defeat, explored and performed the fractured male ego. The post-war male body was presented by these artists as symbolically castrated and recast as a fragile, fragmented being. The scars of war are deeply present in these works, exposed directly to the audience and made manifest in the artists’ flesh. Seen together, the works of Hijikata, Brus and Schwarzkogler exemplify the complex performance landscape of the post-war period, and represent the cross-fertilisation of an inter-cultural dialogue that informed the evolution of the avant-garde throughout the twentieth century.