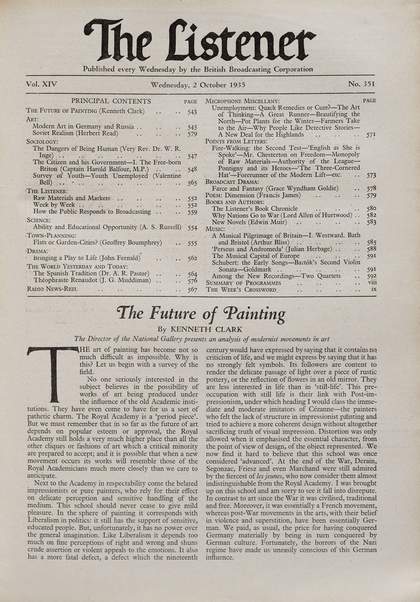

The second half of the 1930s witnessed vigorous clashes in Britain between the competing aesthetics of abstraction, socialist realism, surrealism, and a consciously native extension of the latter which eventually acquired the label of neo-romanticism. The aesthetic debates that surrounded these movements have been the subject of significant art historical research in recent years. Yet very little attention has been paid to the views so vigorously expressed in 1935 by two figures aspiring in a sense to replace Roger Fry (who had died in September 1934) as the dominant commentator on contemporary art. Where it does get a fleeting mention, Kenneth Clark’s essay ‘The Future of Painting’, published on 2 October 1935 in the Listener, is usually taken to reinforce his image as a young fogey, whose ‘establishment’ outlook and image in Civilisation (first televised in 1969) are foreshadowed by his opposition to avant-garde extremism and by his support for ‘Romantic Modernism’ at precisely the moment when Herbert Read, whose riposte to Clark was published in the same magazine a week later, was amongst those manning the barricades for constructivism and surrealism in their tardy English manifestations (fig.1).1 Needless to say, the reality is more complicated, and bound up perhaps with real-world as well as art-world politics.

Fig.1

Kenneth Clark, 'The Future of Painting', Listener, 2 October 1935

It may well be surprising that Clark was only thirty-two years old when he chose to hold forth about contemporary art practice. But what is more extraordinary is that he did so from a position of power and eminence, which normally carries diplomatic constraints. As the article’s tag line stated: ‘The Director of the National Gallery presents an analysis of the modernist movement in art’.2 The place of publication also came with establishment kudos. The Listener magazine, house journal of the BBC, was then at the peak of its prestige as a vehicle for the organisation’s Reithian ideal of mass enlightenment.3 Issues typically featured several essays, sometimes based on radio broadcasts, in which leading authorities summarised new developments in the humanities and sciences, or analysed social issues and current affairs. In this instance, the editors declared that they welcomed Clark’s contribution, since it had ‘always been difficult to secure an effective, reasoned presentation of the aesthetic case against modern art’.4 This was not exactly what Clark himself had in mind; it was certain strands to which he took exception, rather than modern art per se. But the debate certainly struck a chord among the magazine’s more sceptical readership. Subsequent issues of the Listener included a proliferation of letters for and against Clark’s initial statement and Read’s riposte, as well as cross references to a parallel controversy about ‘abstraction’ in contemporary music.5 Such passions had probably not been in evidence since the introduction of French post-impressionism to London in the years immediately preceding the First World War.

Clark’s essay is not so much reactionary as apocalyptic, even traumatised. Contrary to expectation, it opens with a denial that painting even has a future: ‘The art of painting has become not so much difficult as impossible’.6 How does Clark’s announcement of the ‘death of painting’ compare with his numerous post-war successors, or indeed with ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproducibility’, composed by the German philosopher Walter Benjamin in Paris in the autumn of 1935, which famously asserted the political potential of lens-based media, as opposed to the singular, auratic art object?7 To juxtapose those two names in the same sentence, however incongruously, is to register the extent to which aesthetic attitudes were being inflected at this point by the growing challenge of fascism.

In questioning painting’s future, Clark proceeded to pour cold water on the available alternatives. The Royal Academicians were beyond the pale, albeit in tune with popular taste. The ‘belated impressionists or pure painters’ are sensitive, wishy-washy souls, who ‘correspond to liberalism in politics’; their work lacks ‘strongly felt symbols’. In other words, content.8 Their once fashionable post-impressionist followers had now fallen into disrepute, being civilised and basically French in spirit: ‘post-war movements in the arts, with their belief in violence and superstition, have been essentially German. We paid, as usual, the price for having conquered Germany materially by being in turn conquered by German culture’.9 Such outlandish views cast aspersions upon earlier Bloomsbury practice, but chime with the re-evaluation of the native tradition that Duncan Grant and others had recently been promoting in the Studio magazine, a standpoint echoed in fact by Clark in his remarks about the artist’s English roots in a 1934 catalogue essay on Grant’s new landscape paintings.10 In the same year, Clark’s response to the Royal Academy’s major British art exhibition was suitably appreciative, but professed ‘the impossibility of generalising about English art’, beyond noting a certain literary inclination.11 By 1935 generalising about Germany and its baleful impact on modern art came all too easily. In taking on the issue of ‘What Next in Art?’ in the Studio, Clive Bell had lamented the general rise of state control of art, but extended his critique to the ‘rubbish’ that modern German art essentially amounted to, since it mainly consisted of ‘pictures about which German philosophers and Mr Herbert Read can spin theories’.12

Anti-German prejudice may, then, have been in the air within the Bloomsbury circles in which Clark moved. But the sentence with which he followed the passage quoted above brings out the contemporary imperative: ‘the horrors of the Nazi regime have made us uneasily conscious of this German influence’.13 To make such a remark in October 1935 in Britain was by implication to imply sympathy with Winston Churchill’s alarmist stance, and against the prevailing climate of blind optimism and appeasement, in the light of such very recent developments as the Nuremberg Laws, which had come into effect on 13 September. These denied the rights of citizenship to Jews and reduced them to the status of ‘subjects’: the statutes forbade marriage and extramarital relations between Jews and ‘Aryans’, and forbade Jews from shopping in gentile stores, or vice versa, and from attending movies, theatres or strolling in public parks. Some of Clark’s friends, such as Jack Beddington, were Jewish, and he would surely have been repelled by such news out of Germany. Moreover, the very day of the issue of the Listener’s appearance witnessed the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. It is not known exactly when ‘The Future of Painting’ was composed, but it is clear that, for Clark, autumn 1935 was a moment of gloom and foreboding.

Indeed, the same issue of the Listener highlighted the cultural consequences of totalitarianism. A picture spread opposite Clark’s text was titled ‘Modern Art in Germany and Russia’, emphasising the anti-modernism and support for crude realist propaganda that was the common denominator of Hitler’s Germany (epitomised by the Dresden Degenerate Art show) and Stalin’s USSR, a point also forcibly made by Herbert Read in his review a few pages later of the ‘Art in the USSR’ special issue of the Studio.14 ‘The paradox … of two nations diametrically opposed in their social and political ideology, but united on this question of art’ provoked horror in Read. Where force and dogma are elevated above reason and toleration, he wrote, art ‘can only abdicate’.15 In ‘The Future of Painting’, Clark was, in a sense, projecting the same cultural despair onto the native scene.

In more specific terms, the symptoms of decadence in relation to ‘advanced schools of painting’, namely surrealism (known in some British circles as ‘super-realism’) and abstraction, comprised for Clark an ‘extreme reliance on theory’ – a familiar trope in English criticism – and the exclusivity of divergent positions: ‘each group is like a little dissenting sect, sure of salvation while all the rest of the world is damned’.16 Abstract art ‘has the fatal defect of purity’, that is, an inability to connect with the viewer’s existential realities. The surrealists ‘reflect a very great discovery which, during the past twenty years, has influenced the lives and habits of thought of every civilised person’; and they ‘start from one of the fundamental truths of aesthetics, that a strongly held image must precede a work of art’. However, they have come to grief because the artists have felt forced to ‘produce odd, unprecedented images’, evoking ‘vamped up emotional states’ and offering mere escapism and a fraudulent ‘short-cut to spiritual salvation’.17 Such things were symptomatic of the broad impact of German culture that Clark found so distressing. It would not be difficult to portray his views as crass and opinionated. One might even see Clark’s position as loosely comparable here to the more sophisticated position recently adopted by the art critic and theorist Boris Groys; to Clark’s mind the defects of German art and culture under the sign of fascism were somehow embryonic in the attitudes of experimental artists, just as, for Groys, albeit much longer after the event, Stalinism was implicit in the absolutism of the Soviet avant-garde.18

But Clark’s more ‘fundamental objection’ is to the claim made for both tendencies that they are the path of the future, ‘linked with the evolution of a new social and economic system’. This is ‘perfectly false’ – ‘whatever shape society is going to take it is not going to be ruled by people who like cubist and super-realist painting’. Both, in actuality, appeal only to ‘a clique of elaborate middle-aged persons’, and are best viewed as ‘the end of a period of self-consciousness, inbreeding and exhaustion’.19 Again, Clark’s view can be seen as affected by recent developments in Germany and the Soviet Union, where avant-garde experimentation had foundered. His hard-nosed assessment engendered a suspicion that, ‘in the western world the plastic spirit is really exhausted and that art will be lost for many decades’. If a ‘new style’ is to emerge, it ‘can only arise out a new interest in subject matter’, as opposed to ‘art for art’s sake’: ‘We need a new myth in which the symbols are inherently pictorial’, and which ‘must contain the possibility of pictorial symbolism’. Interestingly, he sees the ‘Marxian myth’ as dominant in the present, but lacking in ‘seductive iconography’; ‘The spectacle of Karl Marx at work in the British Museum is dramatic and morally beautiful, but pictorially it is less valuable than a disreputable pagan myth like Leda and the Swan’.20 That comment epitomises Clark’s particular conflicts, as an old school aesthete drawn to the political left as a bulwark against fascism. One might even say that he had arrived in 1935 at a comparable position to that of future abstract expressionists Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, when in 1943 they, too, nailed their colours to the masts of subject matter and ancient myth, having rejected each of the hitherto dominant aesthetics of abstraction, surrealism and realism.21

At any rate, Clark appeared to be grappling with pressing issues of the moment: how to be leftist but not crudely populist, for example, and how to be modernist as well as accessible. But he was also mired at this stage in scepticism and an understandable uncertainty. Herbert Read’s response a week later, insinuated into his review of Ben Nicholson’s show of white reliefs at the Lefevre Gallery, is more self-assured, but also comes over as more of a period piece.22 He trots out the usual arguments about abstraction capturing a deeper reality behind appearances, the analogy with music, and the affinity with modern architecture, with its more direct linkage to the necessary ‘scientific transformation of our cities, our dwellings, the whole structure of our future existence’.23 The best artists are abstract to some degree, and one can either offer support, or one can adopt ‘an attitude of despair, hopelessness and disgust – a world without art’. The only ‘auxiliary duty’ is to ‘work for that change in society which will once more give us a community integrated in spirit and in the pattern of its culture’.24 Such idealism was apparent in Read’s contribution to the 1935 volume Five on Revolutionary Art, and was subsequently extended in Circle, edited by Nicholson, Naum Gabo and Leslie Martin, which was compiled the following year and published in 1937.25 This was a standpoint continuous with the ‘International Constructivism’ that had been widely influential from the early 1920s through to the mid-1930s, but had generally withered in the face of the conspicuous failure of the real world to meet the utopian expectations of the artistic avant-garde.

Two weeks after Read’s piece, Clark’s review of a Rouault show at the Mayor Gallery incorporated expressions of regret that his original piece had given succour to anti-modernist philistinism, which can be seen clearly from the supportive letters appearing in the Listener.26 He himself liked, indeed owned, the work of Nicholson, he protested, but his concern was whether ‘extreme “abstraction” was capable of a development which could satisfy the needs of a future society’.27 Read’s justifications of such work seemed implausible: ‘many of us who enjoy Mr Nicholson’s paintings do so, I am afraid, less as cosmic symbols than as tasteful pieces of decoration’.28 But the larger problem, for Clark, was the connection between abstraction and a formalist aesthetic, by implication that espoused by Roger Fry, that he and many others had grown out of. Art, like poetry, must have some basis, he now believed, in the representation of ‘our common stock of experience’.29 It is worth noting that Clark was more than willing to put his money where his mouth was. He proceeded a couple of years later to give financial support to the mild-mannered social realism of the Euston Road School artists, which was likewise underpinned by a leftist commitment to depicting the collective, everyday environment.30

In 1935 Clark answered Read’s charge of despair by announcing his enthusiasm for modern architecture and for ‘the once minor arts – textiles, pottery, photography, printing, advertisement’, which ‘all show evidence of real vitality’. He continued: ‘In that regeneration of the human spirit, for which I pray as devoutly as Mr Read, the world may regain art, without attempting the individualistic art of the easel picture, abstract or otherwise’.31 Again, one might wonder if such views reveal Clark as a latter-day adherent to the standpoint of the Russian constructivists in the early 1920s, or as a prophet of the American critic Clement Greenberg’s well-known denunciation of easel painting in the 1940s in favour of the large-scale abstractions of Jackson Pollock? More practically, they reflect his enthusiasm for the cohesive visual culture of the Renaissance, but especially his friendships with successful poster designer Edward McKnight Kauffer and with Jack Beddington, supremo of the Shell poster programme, both of whom Clark wrote fondly about in his autobiography.32 This was the ‘golden age’ of the British advertising poster, giving progressive artists a platform in the wider visual environment. One might also adduce Clark’s awareness that Duncan Grant had recently taken on a commission to decorate Cunard liners with murals.33 A modest version of ‘art into life’ was very much current in Britain at this moment.

Finally, Clark turned to the French painter Georges Rouault, for whom ‘painting has not been merely the perception and arrangement of shapes and colours, but the means of expressing a violently emotional attitude towards life’.34 He proceeded to discuss the impact of Toulouse Lautrec, medieval stained glass (especially evident in Rouault’s ’extraordinarily beautiful landscapes’), and the affinity with children’s art, suggesting that ‘Rouault’s style, which has hitherto seemed so isolated and personal, may become a point of departure of the future’.35 Art, Clark insisted, ‘must once more become simple and passionate’. Rouault’s ‘very defects, his over-emphasis and fanaticism’, he concluded, ‘will have a stronger appeal to the immediate future than Mr Nicholson’s discreet and rarefied harmonies’.36

In a letter drawing the dispute to a close, and likewise in a conciliatory spirit, Read remarked: ‘In our prophecies we give expression to our personal prejudices, and there the discussion must end’.37 That seems judicious enough. But, looking back, what is interesting about the debate is precisely that impulse to look forward, rooted in a sense that organic evolution from the recent moderate modernist past was not an option. Extreme times demanded an authentic renewal of artistic language. One could neither keep calm, nor just carry on. For Read, the eternal optimist, European abstraction and surrealism were pointers to the future, where good would triumph over the all too visible evils of the present. For Clark, only Rouault and his latter-day medievalism provided the fine art solace he could reach for, and it was the widespread engagement with design that intimated a renewal of popular visual culture.

The appearance of the article coincided precisely with Clark encountering Graham Sutherland, firstly in the exhibition of Shell poster designs that Clark agreed to open. He recalled in his memoirs how ‘ever since Oxford I had been hoping to find an English painter of my own generation whose work I could admire without reserve … the visionary intensity with which Sutherland looked at small corners of the Welsh coast … seemed to place him in the same tradition of lyrical art as Blake, Turner and Samuel Palmer’.38 Sutherland had drawn on Palmer in his early etchings, while Clark had already acquired works for the Ashmolean and his own collection. Now Clark evidently viewed Sutherland as Palmer reborn, while Sutherland renewed his own interest, but endowed Palmer’s literal darkness with a metaphorical resonance that distilled the contemporary atmosphere of threat.

In ‘The Future of Painting’ Clark had in a sense cleared his aesthetic decks, with Rouault the last man standing. Once he had discovered Sutherland, John Piper and other artists that were to be associated with neo-romanticism, it became clear to him that painting no longer seemed quite so ‘impossible’. As the art historian Alexandra Harris notes, Clark’s shift from anti-formalism to pro-Englishness is registered in the progression between the 1936 introduction and the 1939 preface to his edition of Roger Fry’s Slade Lectures.39 In an essay for the Penguin Art in England volume published in 1938, which had initially been triggered by the centenary of John Constable’s death, Clark was able to present the great Romantic painter as the ‘most English’ and the ‘most universal’ of painters: ‘No-one else would seem to show so clearly the way English painting might go’, which meant immersion in the native scene and resistance to ‘the picture-making formulas of continental schools’.40 It might be argued, then, that the growing impulse towards ‘Romantic Modernism’, as the 1930s went on, represented, for Clark and others, not just a defensive response to an imported modernism but also a positive reassertion of British cultural identity, progressive in political and cultural terms, at a time when much less benign versions of nationalism were being imposed and threatened elsewhere. In a modest way, one might say, the fight for ‘civilisation’ had been joined as far back as 1935. The idea that the neo-romantic aesthetic of Clark and others was in some oblique sense ideologically motivated, and not just a provincial rejection of the modernism that had belatedly flowered in England, can be viewed against the backdrop of the crass neoclassicism with which the fascist regimes had clothed themselves.

At the same time, Clark ought not to be viewed too narrowly as a Little Englander. Rouault seems to have remained his favourite contemporary artist – in Another Part of the Wood (1974) he described putting down a deposit on Rouault’s ‘marvellous etchings’ from the Miserere and War album (Miserere et Guerre) which fell foul of dealer Ambroise Vollard’s death during the wartime dislocation.41 He acquired in 1937 an intense, abstracted landscape by the surrealist André Masson, Ibdes in Aragon 1935, which he subsequently gave to the Tate Gallery (Tate N05646).42 In 1939 Clark asserted, admiringly, that ‘Picasso is most himself when he is violent’.43 And in Sutherland he encountered an artist strongly committed to the fusion of native traits and tradition with a cosmopolitan awareness, which produced an emphatic resistance to his being pigeonholed as a patriotic ‘neo-romantic’.44 It might equally be said of Clark that it was an aesthetic preference for expressive modes of figuration, rather than a national commitment per se, that governed his taste and collecting in the wake of ‘The Future of Painting’.

By way of a footnote to the 1935 article, it can be seen that a sense of an ending came quite naturally to Clark, from the evidence of the lectures and from his book Landscape into Art, first published in 1949. Sutherland provided a design for the original cover, and his art was clearly at the back of Clark’s mind when he noted the disconcerting ‘disappearance of a humanist scale – the way in which a thorn tree or a group of dead thistles suddenly assumes colossal proportions’.45 As he drew the book to a conclusion, however, Clark ruminated upon the recent disruption by science of received ideas of ‘nature’: ‘we have even lost faith in the stability of what we used hopefully to call “the natural order”; and, what is worse, we know that we ourselves acquired the means of bringing that order to an end’.46 In the present circumstances, escape into an ideal world is impossible. The best prospects for landscape painting reside in ‘an extension of the pathetic fallacy, and the use of landscape as a focus for our own emotions’.47 The hope Clark placed in expressionism, and in the coming of another Grünewald at a time of ‘our new wars of religion’, sounds like a veiled manifesto for the work of Sutherland, but also like a variation on the apocalyptic sensibility that had underpinned his paean to the art of Rouault in 1935.48 In both the article and the later book Clark sought to historicise the present. However schematic the outcome, his efforts to understand and critically analyse contemporary practice in terms of underlying historical forces and mentalities reflected an immersion of some sort in Marxism, and perhaps in the methodologies espoused by the Warburg Institute art historians, newly arrived in Britain when Clark was compiling his article in 1935. His own writings, in turn, now require more rigorous historicisation than they have received hitherto.