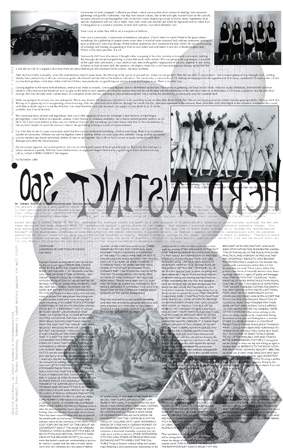

Fig.1

Fia Backström

Herd Instinct 360° 2005–6

Printed paper

© Fia Backström

On the evening of 29 November 2008, I attended a performance by the Swedish artist Fia Backström (born 1970) at the Western Front, an artist-run centre in Vancouver. Speaking from the stage of the institution’s Grand Luxe Hall, Backström addressed her assembly with the persuasive, hypnotic tone of a motivational speaker or religious leader. Her subject was groups: ‘communes of labour’, she began, ‘brainwashed consumer combatants, group therapy, exclusive clubs and corporate get-togethers, guerrilla marketeers, virtual communities of no contact or sharing … fists for some cause: to the Left, the Right, and together; masked faces on the catwalk, romantic remakes of coming together with no forward vision, displaying a scorn for reality’.1 From its first word her speech was cued to a rapid barrage of images. Projected on a screen behind her, few were on view for more than a second, and often they seemed, in rhythm with the artist’s monologue, to flash before my eyes before they could be perceived. Sometimes these pictures illustrated and affirmed her words – ‘fists for some cause’ drew up Black Panther fists and praying hands, while ‘masked faces’ produced a balaclava-wearing militant – but they just as often offered a bewildering counterpoint. Pillaged from a Google Images search for the phrase ‘community’, her presentation bombarded its audience with ads, news images, Flickr photographs, cartoons, trademarks, and stock photographs, frequently bearing the digital ‘watermark’ of their origin. In a single minute appeared (to call up an arbitrary sequence) Dutch still-life paintings, sushi advertisements, Jesus, George W. Bush, Steve Jobs, Hugo Boss, Maurizio Cattelan’s sculpture him 2001 (private collection), sports, street celebrations, Black Panthers, Nazis, woodcuts of Aztec human sacrifice, Bataille’s acéphale and more. The effect, for this writer at least, was a kind of exhilaration, as I absorbed the logic of her image-juxtapositions, and attempted to justify them to her spoken narrative.

Fig.2

Fia Backström

Herd Instinct 360° 2005–6

Printed paper

© Fia Backström

Titled Herd Instinct 360° 2005 (figs.1–2), Backström’s presentation called to mind the artists, writers and thinkers of the Independent Group (IG), not only in her questioning approach to the conditions of audience in a transformed mass culture, but in her attention to how images (of leisure, social life, consumerism, pleasure, resistance, conspiracy, warfare and so on) work now, in a confounding and ever-expanding symbolic economy. In particular I was drawn to think about ideas put forward by the writer and curator Lawrence Alloway in the late 1950s. I thought of his 1959 essay ‘The Long Front of Culture’, where he argued that fine art and popular culture, which for generations before had been carefully separated into an elitist hierarchy of high and low, now lived in a free-ranging and flowing ‘continuum’ of mass media. To live in the present, Alloway argued, was to accommodate oneself, and one’s creativity, to this fact: ‘What is needed’, he wrote in his ‘Personal Statement’ of 1957, ‘is an approach that does not depend for its existence on the exclusion of most of the symbols that most people live by’.2 From five decades’ distance, Backström had responded to his call.

This essay, then, is imagined as a prehistory of Backström’s and our present predicament. It elaborates on the evolution of the long front in the discourse of the IG, and offers a critical précis of some of Alloway’s claims. Moving forward in time, it then concludes with two criticisms of the long front concept: first, by indicating some limitations in the essay’s version of the IG position and practice; and second, by interrogating what happens when the conditions of culture in an age of mass production and consumption become, less something that needs finally to be recognised and celebrated (which is what Alloway argued), than a pervasive and total assumption, a kind of ground level for culture. With Alloway’s Oedipal battle with his forebears long since resolved in his favour, and ‘keepers of the flame’ on the run, what forces now structure the cultural field? What is it like to live in the long front of culture?

Lawrence Alloway occupies a special place in the archaeologies of pop art. During the ‘First Pop Age’ (as Hal Foster has called it),3 Alloway was a key participant in the Independent Group, a ‘small, cohesive, quarrelsome, abrasive group’ that held discussions about modernist art, science and popular culture at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London in the early 1950s.4 During the IG’s early sessions between 1952–4, Alloway was a curious onlooker, but after the departure of the architectural historian Reyner Banham (1922–1988) he became, in short order, the group’s organiser, theorist and self-appointed spokesman, as well as the ICA’s assistant director.

In his 1958 essay ‘The Arts and the Mass Media’, Alloway exerted a claim to have been among the first to put the phrase ‘pop art’ into print,5 and in the 1960s Alloway was, along with Banham, the consolidator and promoter of the IG as the vital precedent for American pop.6 After a move to the United States in 1961, and a new job as curator at the Guggenheim Museum, Alloway became a critic and ardent supporter of American pop artists: the writer Lucy Lippard included an essay by Alloway in her early history of pop published in 1966,7 and Alloway published in 1974 his own book on the subject, American Pop Art.8

As critic and curator, Alloway joined a voracious appetite for all kinds of culture – from so-called high modernism to Hollywood Westerns, pulp science fiction, comic books and industrial design – to a hard-nosed commitment to bring sharp critical judgement to bear on each of these spheres equally, almost as if such a free-ranging criticism could, by its own force, erase deeply felt divisions between fine art and the best products of an exploding consumer culture. The modernist critic Clement Greenberg, whose attentive criticism Alloway nevertheless admired, was, in light of this new attitude, relegated to the status of blinkered ancestor. So too were the attitudes of latter-day surrealists, such as the critic Herbert Read and the writers E.L.T. Mesens and Roland Penrose, among the founders of the ICA in 1947, suddenly cast as out of date, hopelessly snooty and inert. The ICA’s director Dorothy Morland would later describe a ‘dissatisfaction amongst a group of [the ICA’s] younger members … who felt they weren’t getting an opportunity to exchange views and who didn’t fit into the pattern perhaps that was set by Herbert Read and some of the older members of the committee’.9 Early meetings of the IG would devote energy to attacks on the older members’ perceived ‘aestheticism’,10 with particular vitriol reserved for modernists T.S. Eliot and Roger Fry, alongside the British inheritors of the Bauhaus and those, like Penrose and Read, associated with a ‘pro-School of Paris’ position.11 The social form of the avant-garde was evaluated and discarded, in favour of a permissive yet fractious working-group format.

Here are the sneering epigrams that kick off Alloway’s 1958 diatribe ‘The Long Front of Culture’:

The abundance of Twentieth Century communication is an embarrassment to the traditionally educated custodian of culture. The aesthetics of plenty oppose a very strong tradition which dramatises the arts as the possession of an elite. These “keepers of the flame” master a central (not too large) body of cultural knowledge, meditate on it, and pass it on intact (possibly a little enlarged) to the children of the elite.12

Capturing something of punk rock’s irreverence avant la lettre, the intensity of these sentences is unmistakable, even from fifty years’ distance; they explain the IG’s attraction for later writers like Dick Hebdige, who figured the group as godfathers not of pop art but of punk’s nihilistic version thereof, with Alloway playing the part of the rascally uncle of Malcolm McLaren, the manager of the Sex Pistols.13 Recollections from IG members give this reading credence: ‘I think Lawrence Alloway was interested in theory but what he wanted was ammunition’, remembered the writer Roger Coleman in a 1983 interview.14 The artist John McHale, Alloway’s partner-in-crime in the IG’s latter days, recalled in 1977 that the group ‘was very historical in one sense, but it was interested in demolishing history. It was … very iconoclastic; one was very happy with that and so we sort of went on attending’.15

Alongside mischief and ambition, Alloway had the ad-man’s gift for compression. Borrowing certain phrases and lines of thought from the IG’s sprawling debates, he carved them into weaponised slogans: ‘pop art’ itself, alongside ‘the tackboard aesthetic’, ‘the fine art-pop art continuum’, ‘the aesthetics of plenty’, and ‘the long front of culture’. He elaborated these ideas over the course of short, sharp pieces of critical prose published in London and Cambridge journals in the late 1950s and early 1960s.16 These writings codified and consolidated an IG ‘position’ on culture in retrospect, through a process of deferred action.

A short history of the ‘Long Front of Culture’

First advanced in 1959, the phrase ‘the long front of culture’ (and its somewhat clumsier corollary, ‘the fine art-popular art continuum’, later abbreviated to ‘fine art-pop art continuum’) aimed to describe an emergent attitude among the artists, architects, designers and critics connected to the IG: a fascination with, and complex manipulation of, the artefacts of a new, modernised American popular culture. In the place of an obsolete hierarchy of an imperilled modernism and a debased kitsch (the boundary between which might alternately be policed and transgressed), Alloway imagined instead a single continuum or ‘front’, where fine art and popular culture not only existed on equal terms – Picasso and bug-eyed monsters, Duchamp and lux upholstery, the Bauhaus and lifestyle magazines – but competed for the attention of a new sort of mass audience.17 This was a mass audience, Alloway’s essay averred, composed neither of connoisseurs nor mindless consumers, but rather of cultural agents ‘specialised’ by their different identities and desires. This theory, then, attempts to explain why we have variety on supermarket shelves: to respond to the desires of different consumers who not only purchase commodities, but consume the difference among them. Which is to say, simply, that this was no programme for a ‘pop art’ as the genre is now commonly understood, but a broadside attack on perceived provincialism and cultural elitism of all kinds, and a call for a fine art that might be as sophisticated, as enthrallingly weird, as a Hitchcock movie, a sci-fi magazine or an advertisement for Chevrolet.

Here I wish to offer a genealogy of this argument, drawing in part on my previous writing on the subject.18 The long front of culture was born not during Alloway’s involvement with the Independent Group, but was formulated in the as-yet-unnamed group’s first meeting, where the artist Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005) presented his collection of cuttings and collages from magazines, cadged from American military personnel stationed in Britain after World War II, using an epidiascope opaque projector. Paolozzi had plastered his studio walls with images torn from their pages. Juxtaposed in this domestic context, the tearsheets seemed to sprout new meanings. Compiling connections between the pose of a burlesque dancer and that of an air traffic controller, or between a breast (from a pornographic magazine) and a peach (from an advertisement for canned fruit), supposedly disparate images became conjoined, and new associative codes discovered. Recorded in those media, history’s traumas were reassembled in Paolozzi’s collection as if the depictions of a private iconography, as if dictated by desire alone.

At the time the presentation was regarded as a disappointment. Having seen the material already, and having built his own pop collection, the artist William Turnbull was dismissive. ‘It wasn’t such a revelation to me,’ he said, ‘I’m sure it was to some’.19 Another attender, the artist Nigel Henderson, explained that if Paolozzi’s epidiascope show was a failure, ‘it was because the visual wasn’t introduced or argued (in a linear way) but shovelled, shrivelling in the white hot maw of the epidiascope. The main sound accompaniment that I remember was the heavy breathing and painful sighing of Paolozzi to whom, I imagine, the lateral nature of connectedness of the images seemed self-evident’.20

’The lateral nature of the connectedness of the images’, which need not be ‘introduced or argued (in a linear way)’: this was Paolozzi’s radical proposal, one that Alloway accepted. ‘One of the things I think is terribly important about Paolozzi’, Alloway remarked in an interview for the documentary film Fathers of Pop (1979),

is that he was a full-time artist. Wherever he went he was, you know, bending things, drawing things, or turning paper plates into something, so that he was habitually an improvising working artist. He and I used to go quite a lot to the London Pavilion in Piccadilly which in those days was showing Universal horror films … so he was kind of someone who had this itchy creativity on a continuous basis, always being bombarded by mass-media imagery. And the example of seeing this happen to someone, I think sort of relaxed me and made it easier for me to go to the lecture at the Tate Gallery in the afternoon and go to the London Pavilion as soon as I could get out of there in the evening. He’s been influential, I think, in setting up this notion of the fine art-pop art continuum – the touchability of all the bases in the continuum.21

Returning to our genealogy: Reyner Banham had been one of the few to see the value of Paolozzi’s lecture; under his leadership the group would take up both Paolozzi’s voracious appetite for pop and his epidiascope show’s ‘lateral’ method, in a series of discussions, lectures, and exhibitions. During Banham’s tenure, there was the 1953 ICA exhibition The Parallel of Life and Art, organised by Paolozzi with Alison and Peter Smithson, in which photographs were mounted on matte board and suspended by brass eyelets, according to an apparently random, non-hierarchical order. From this matrix were produced dizzying propositions: that abstraction recapitulates the physical structures of form and matter; that hieroglyphic icons obey a biological imperative; that material artistic production and evolution are co-extensive; that up-to-the-minute technologies of imaging make it possible literally to visualise the past.22 Such claims were the potential value of Paolozzi’s permissive cross-thinking – even as they deliberately forestalled traditional forms of interpretation, substantiation or argument.

Only then, after Banham’s departure, was the ‘lateral’ idea taken up by Alloway and his co-conspirator, John McHale – who attended together just one of Banham’s run of meetings – as a readymade, if as yet uncodified concept. If they did not invent the idea, McHale and Alloway were the ones who named it as such, who argued it publicly and vociferously, and whose voices gave it a polemical and critical charge. In its fine art-pop art phrasing, then, the idea gained critical purchase during the discussions convened by Alloway and McHale at the ICA between 1954–5. It was the operating principle of Alloway’s public programmes in a more general way as well; they make no substantive distinction in critical approach between lectures on horror comics, or Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture, discussions of Hollywood heroines or working over Richard Hamilton’s most recent exhibition.23

McHale was the first to put this new principle into print, in a commentary on the architect Walter Gropius and the Bauhaus that appeared in 1955. The Bauhaus had imagined the art school as a factory, McHale argued, and the machine as an extension of the hand. By the 1950s, however, things had changed: not only had the machine become ‘autonomous’ and ‘synthetic’, but, ‘”a fine art-popular art continuum now exists”, and so, where the Bauhaus had its amateur jazzband and kite festivals – we have bop and Cinemascope’.24 For his part Alloway offered this account of a new horizontal ‘field’, synonymous with McHale’s ‘continuum’. ‘When I write about art (published) and movies (unpublished)’, Alloway wrote, ‘I assume that both are part of a general field of communication. All kinds of messages are transmitted to every kind of audience along a multitude of channels. Art is one part of the field; another is advertising’.25 This was offered at the time that the IG itself ceased to meet and Alloway unwillingly exited the ICA and ‘accidentally but happily’ moved to the United States.26

Alloway’s proposals

Alloway and McHale’s new pluralist approach would find its most programmatic description in ‘The Long Front of Culture’. The implications of Alloway’s reformulation, from the language of science (‘continuum’) or communications theory (‘messages’, ‘channels’ and ‘fields’), to the anomalous, combative ‘front’, bears elaboration. Alloway’s phrase evoked both China’s Long March (the year-long, six-thousand mile retreat of Mao’s Communists from Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Army in 1934–5) and Britain’s leftist Popular Front of the 1930s (which comprised both Communists and the Labour left).27 In suggesting these antecedents, it did so to replace them, and to burlesque their stoicism, displacing class politics with capitalist semiotics. Other resonances sound as well: mass culture is imagined as an immense line of battle, about to overwhelm a beleaguered, elitist opposition; and the forward boundary of a storm, producing a momentous and inevitable shift in atmosphere.

The essay makes its points quickly. First, Alloway writes, ‘Mass production techniques, applied to accurately repeatable words, pictures, and music, have resulted in an expendable multitude of signs and symbols’.28 This proliferation of repeatable, expendable signs demands a shift in our notion of what culture is, and how we should consider it. Rather than pursue an ‘aesthetic of exclusion’, artists and critics should map out their communicative patterns, ‘in a descriptive account of society’s communication system’.29 Secondly, the techniques of sociology – and emphatically not interpretative critique – are the best way to understand this shift. Close reading is out. ‘Observant and “cross-sectional” in method,’ Alloway writes, ‘sociology extends the recognition of meaningful patterns beyond sonnet form and Georgian elevations to newspapers, crowd behaviour, and personal gestures.’30 Thirdly, the mass media ‘act as a guide to life defined in terms of possessions and relationships’ – and this need not be construed as a disaster; in fact it is quite exciting and revealing, because this kind of personal inventory presents ‘a treasury of orientation, a manual of one’s occupancy of the twentieth-century’.31 Commodities are pedagogical, they teach their consumers ‘lessons’ about how to live and relate to one another. Analysed as such, we can learn useful things about how the people who make up the ‘mass audience’ assemble themselves from these repeatable ‘signs and symbols’, how they relate to one another and act in the world. And fourthly, the ‘mass audience’ is a fiction; in fact widespread industrialisation produces not standardisation but diversification, in the form of ‘a wide choice of goods and services to everybody (teenagers, Mrs. Exeter, voyeurs, cyclists)’.32 And the consumer of such commodities retains, through this myriad of choices, the possibility of ‘private and personal deep interpretation’.33

The concept was timely, in tune with the arguments of the sociologist Richard Hoggart’s The Uses of Literacy (1957), as well as arguments about ‘mass culture’ being elaborated by the cultural critics Marshall McLuhan and Raymond Williams among others.34 These theories foresaw magazines and programmes in cultural and visual studies, as well as a certain sort of postmodernism. Alloway’s theory of the ‘touchability of all the bases in the continuum’, one might even argue, imagines Google’s image search engines and ‘the long tail’ avant la lettre, as well as the current, constant flux between celebrity culture and contemporary art.35 Today we live in the long front, like it or not. But now that it has become a dominant condition, does Alloway’s description retain critical bite? It seems to me that the ideas Alloway set out seem, fifty years on, to stand as valid and even obvious descriptions of his moment, and prescient in the ways I have marked above. Yet the article has certain stark limitations as well, on which I will now aim to elaborate.

Critique one: absent cause

The great transformations described by ‘The Long Front of Culture’ appear absent of any explanation or cause, as if by magic. Except perhaps in the ironic crypto-militarism of the title, the reasons behind this remarkable expansion of productive capacities are obviated. American industries that had devoted themselves to overproduction in wartime, often reaping great profits in doing so, aimed to find ways to sustain this lucrative overproduction curing the post-war period. The war machine redirected its advanced techniques to the domestic theatre, and the production of this sudden, enthralling rush of objects and images for export. Alloway’s short-sightedness could be more easily excused, were it not worked over elsewhere in the IG circle: Richard Hamilton, by comparison, was doing more to parse the reasons behind these remarkable new rhythms of consumption, in his 1960 article ‘Persuading Image’ – which explored the evolution of the design profession and, following American designer George Nelson, aimed to explain consumer culture’s new emphasis on expendability – and elsewhere.36 Paolozzi, for his part, had intuited quite effectively this short circuit between the war machine and the new consumer society in collages such as I Was A Rich Man’s Plaything 1947 (Tate T01462).

Alloway was more perceptive in his account of the effects of this new expansion. A culture of ‘plenty’ meant a radical uptake in the amount of things that could be counted as culture, but also, he understood clearly, a momentous demographic expansion among the potential audience of culture. Three decades later the American cultural theorist Fredric Jameson would expand on this idea in his book Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, speculating that whole categories of ‘postmodern’ experience – the waning of historicity and the ban on ‘totalization’ – might be attributed to ‘the gravitational mass of sheer synchronic numbers’ in this expanded world.37

Alloway’s myopia, however, impaired a deeper understanding of his moment, and of the artworks produced by his peers and friends. His dream of infinite abundance was tied both to the tremendous expansion of productive abilities, but also to new operations of the market: its innovative cycles of fashion and obsolescence, accelerated in the post-war period, and to novel configurations of finance, particularly an expanded and popularised credit market. ‘The Long Front of Culture’ was published in an era of easy credit, enabled by the Hire Purchase controls in the United Kingdom.38 These developments gave consumers the ability to wager their future labour against goods in the present, but the boom markets in which the long front became a fact of life were similarly prone to disaster, tying the long front to a post-war cycle of consumer elation, to be followed by an inevitable (yet, for Alloway in 1959, unimaginable) crash.39 ‘Are We Enjoying Too Much Tomorrow Today?’ warned Picture Post in 1956, in a lurid inversion of the ‘catchy but ludicrous’ title of the IG exhibition This Is Tomorrow.40 And indeed they were: as built-in cycles of fashion and obsolescence failed to keep up with the velocity of production, in the late 1960s Western markets succumbed to over-saturation, glut and spiralling inflation.41

As the art historian David Mellor explained in his essay ‘”A Glorious Techniculture” in Nineteen-Fifties Britain’, the IG inhabited this brittle mindset in the 1950s: on the one hand, a celebratory fascination with American pop culture and industry, and on the other, fantasies of ruin, terror, monstrosity, and apocalypse.42 In the artist Magda Cordell’s bloody cyborgs or Paolozzi’s sculptures, this schizoid worldview was played out clearly enough, but Alloway’s pattern-recognition, so acute in certain ways, elides this weird thread almost entirely. In doing so he misses the doubleness of both mass culture and the artworks now on equal footing with it. Driven by fantasies of a consumerist cornucopia just around the corner, the aesthetics of plenty came with a cruel tax of market precarity and political instability, traces of which were carefully erased from Alloway’s writing. Meanwhile, grotesque images of the obsolete machine crept over the horizon, comic vestiges that nevertheless refused to sit still.

Critique two: a new order for a new economy

Let me recall McHale’s provocative claim that the discussions of the IG were interested in ‘demolishing history’. This demolition amounted to a clearing, a levelling-out, a polemical reorientation to products of culture that served as a basis for novel and exciting associations, as well as a new body of image-material for art to work with and through. Artists ought no longer go up against the best art of the past, in patriarchal, diachronic competition with a pantheon of legitimated foes (along the lines set out in T.S. Eliot’s ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, for example) but would instead participate – horizontally and synchronically – in an expanded pan-disciplinary field. Accept this new situation with clear eyes and artists might finally exit the smoky Bohemian café and emerge into the cosmopolitan common culture, Alloway and McHale hoped, as professionals in their own right.

The ‘tackboard aesthetic’, Alloway and McHale proposed, was a primary technology of this demolition and reorganisation; a way for ‘artists as consumers’ and a mass audience together to make visible how they might come to terms with this new ‘multitude of signs and symbols’.43 That is, through mapping out personal arrangements, discovering affinities, and recognising patterns, though from where, and from which aspects of the subject such ‘private and personal’ agencies might be realised, is left rather indistinct. This was not a new habit for artists: ‘[we were] making a principle out of something which was not at all that new’, Toni Del Renzio acknowledged. ‘Artists had always done it but we believed it was a technique.’44 And not only a technique, but, following Alloway’s coinage, an aesthetic, that played out in collages, paintings, and exhibitions like The Parallel of Life and Art (ICA, 1953) and Man Machine and Motion (Hatton Gallery, Newcastle and ICA, 1955), with equal intensity.

In the wake of the long front, such aesthetics have become pervasive. A tackboard aesthetic now dominates the world of contemporary art, not just in the common-enough appearance of tackboards themselves and source materials in the scene of exhibition, but in the frequent appearance of constellations or arrangements of images or objects (to say nothing of those artists for whom collecting takes on a more conceptual or syncretic dimension, such as Gerhard Richter and Andy Warhol). It serves as the prevailing modality of exhibitions under the sign of the ‘thematic’, and governs the extension of a curatorial logic to the furthest corners of culture, from social events to archives, dinners to symposia. More encompassing still, the tackboard is the axiomatic format of life lived online, for blogs and Tumblrs, iPhoto, Google Images and Flickr, Facebook and Powerpoint. With them, the tackboard aesthetic administers the construction and transmission of knowledge, personal identity and social interaction.

To live in the present is to arrange images: producing, scanning, tagging and sorting them, examining them for patterns or associations, uploading them, building archives and image sets of ‘randomised’, ‘expendable’, ‘repeatable’ signs, in a constant flow between different spheres of culture. In this process, works of art – as Alloway saw so clearly – exist on the same level and in the same field as other sorts of images. The IG might have loved the surreal results of a Google Images search for ‘Richard Hamilton’, which gathers up images from the artist and his namesake, the basketball player for the Detroit Pistons, with the added, wicked irony of the team’s tribute to the mass-produced, ultramodern Detroit automobiles the IG so revered. The very format of the computer’s screen seems to insist on such randomised coincidence of disparate elements. On our screens we inhabit the conceptual debris of a computer’s confluence of labour and leisure, personalisation and things we share with many others, not least the trays and frames of Apple’s information architecture.

In the suspense of his polemic, Alloway might have found such a perplexing state of affairs thrilling, both for its democracy and the peculiar, yet quasi-meaningful juxtapositions it enables. Hindsight allows us to be more ambivalent. By way of conclusion, allow me to give that ambivalence a voice. Firstly, to sort and juxtapose images is to understand them only so far, and primarily in relationship. Something of the strange self-containment of images goes missing in the process. ‘For me, the sine qua non of the image is alterity’, writes French cinema critic Serge Daney, but this alterity is lost when images have meaning only in a busy, changeable matrix, and are never confronted as such, alone.45 Secondly, the apparent democracy of the long front is today subtended by abstract, aniconic hierarchies that, unlike Alloway’s ‘custodians of culture’, are far more difficult to visualise or name, much less resist.46 French sociologist and philosopher Jean Baudrillard referred enigmatically to this, in the 1970s and after, as ‘the code’47 Google may call it their ‘search algorithm’. These aniconic systems channel our participation in ways that we can hardly verify or guess. Leaving aside the already questionable idea of a democracy of consumer choices, this participation is not democratic or egalitarian in any real sense.

Finally, and at more length, Alloway’s discomfort with the languages of socialism – which he may have associated with ‘elitists’ like Penrose and Greenberg, or (just as likely) with totalitarian regimes in the Eastern Bloc – prevented him from applying Marxian ideas that might have given the long front a more critical perspective. I mean, specifically, exchange value and commodity fetishism, and the transformations they enact on ‘the multitude of signs and symbols’ in a consumer society. It would be Baudrillard, then, and not Alloway, who would complete the idea of the long front in his leftist writing in the early 1970s – in particular his 1972 For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign48 – by taking Alloway’s sociological and semiotic understanding of mass culture to its logical ends, but with the arsenal of political economy at his disposal.49 Baudrillard would aim to describe, in terms derived from Marx and buttressed by anthropological and semiological theory, the transformations of a consumer society that the theorist of commodity fetishism could hardly have imagined. Take for example Baudrillard’s memorable analysis of the ‘semiological reductions’ enacted by the commodity fetish, scrutinising the example of the sun:

The vacation sun no longer retains anything of the collective symbolic function it had among the Aztecs, the Egyptians, etc. It no longer has the ambivalence of a natural force – life and death, beneficent and murderous – which it had in primitive cults or still has in peasant labour. The vacation sun is a completely positive sign, the absolute source of happiness and euphoria, and as such it is significantly opposed to non-sun (rain, cold, bad weather). At the same time as it loses all ambivalence, it is registered in distinct opposition, which, incidentally, is never innocent: here the opposition functions to the exclusive benefit of the sun (against the other negativised sun). Thenceforth, from the moment it functions as ideology and as a cultural value in a system of oppositions, the sun, like sex, is also registered institutionally as the right to the sun, which sanctions its ideological functioning, and morally registered as a fetishist obsession, both individual and collective.50

Inasmuch as the mass media, according to Alloway, ‘orient the consumer’ and ‘give perpetual lessons in assimilation’,51 this, I would argue, is what they teach: that signs are positive, direct, and acquire meaning and value only in relation to other signs.

For Alloway this reordering of the sign was more-or-less salutary. It provides a ‘fund of common information in image and verbal form’, while making room for ‘highly personal uses’.52 This new popular culture of signs no longer demanded a guild of interpreters, he argued. It was ready to be consumed and understood by all, on their own terms and according to their own desires. Alloway’s democracy, however, was Baudrillard’s hell. After transforming the material world, the philosopher argued, capitalism had turned to the structures of language. The wages of this development were calamitous: the psychic and the social were collapsed and the unconscious colonised; real labour and desire were replaced by a simulacral ‘system of oppositions’ that privileged one sign over another; these abstractions then played out ‘on the order of power’ and on life itself.53

However we choose to read it, semiological reduction is a necessary operation of the tackboard aesthetic, at least as it played out in the wake of Alloway’s article. In the course of borrowing, sorting-through, mapping and arranging, images become flat and positivistic ‘messages’ to organise on a blank field. Something of their complexity and ambivalence disappears in the process.

This was not true for the artists of the IG, it should be noted. Compare, for example, Alloway’s group’s didactic contribution to This Is Tomorrow54 – a tackboard of tearsheets from magazines linked by theme – to Paolozzi’s Bunk! collection, or his group’s contribution to the same exhibition, and the differences become clear. How does one justify, in Alloway’s terms of sign and message, the wild dissonance of Paolozzi’s associations, or the aggression so often evident in the forced proximity of disparate things? Are Paolozzi’s collages a ‘treasury of orientation’ to a new mass culture, or the production of disorientation within its consumer matrices? Paolozzi embodied, for Alloway, an ‘itchy creativity on a continuous basis, always being bombarded by mass-media imagery’, yet this paradigmatic character eludes the very theory he inspired.

In articulating these criticisms of ‘The Long Front of Culture’, my intention is not to show how Baudrillard got it right. Instead, historical distance allows us to see that democracy and domination, free choice and imprisonment, were two sides of the same ideological process. What is needed in the present, then, is not a repetition of Alloway’s powerful celebration of mass culture and pop art, but instead, a history and dialectic of the transformations he described so well. This proposes too an important role for artists and theorists living in the long front: to discover, in the detritus of publicity and commodities, a new dissident language, and to render personal ‘treasuries’ as public knowledge. Or, to borrow the title of another of Fia Backström’s works, we might imagine them as new orders for new economies.55