In April 1966 Barnett Newman’s exhibition The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani opened at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (fig.1).1 The fourteen large black and white paintings in the series were physically imposing (each one measured 1.5 x 2 metres), and created, according to Newman’s plan, a sacred visual experience in the museum’s famous secular, spiral galleries designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Organised by Guggenheim curator Lawrence Alloway, it was Newman’s first solo museum exhibition – a hard-won feat for the artist who had struggled for years to achieve the critical and institutional success enjoyed by some of his abstract expressionist peers. Newman’s late recognition is surprising given his centrality to the New York school. He is, for example, credited with naming the seminal, short-lived art forum ‘Subjects of the Artist’, a title that aptly named its depth and intention in abstraction.2

Fig 1.

Installation view of Barnett Newman: The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 1966

Photo:Robert E. Mates © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

In 1950 Newman led his peers in a campaign to denounce the Metropolitan Museum for not recognising abstract art.3 The open letter appeared on the front page of the New York Times on 22 May and was followed by the now legendary photograph of the signatories, dubbed the ‘Irascible Eighteen’, in Life magazine. They were forever linked through the Life image as the first generation of abstract expressionists.4 Irrespective of his position at the time, but perhaps hinting at how his legacy would evolve, Newman was posed centrally in the photograph.

Barnett Newman

Moment (1946)

Tate

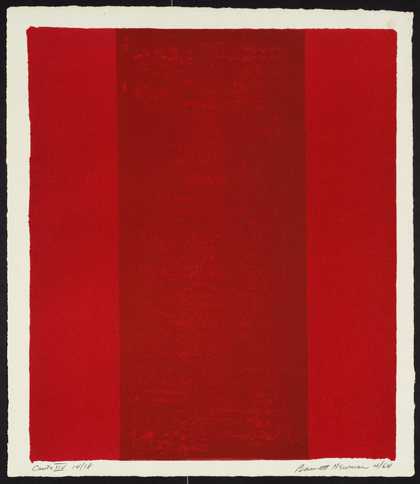

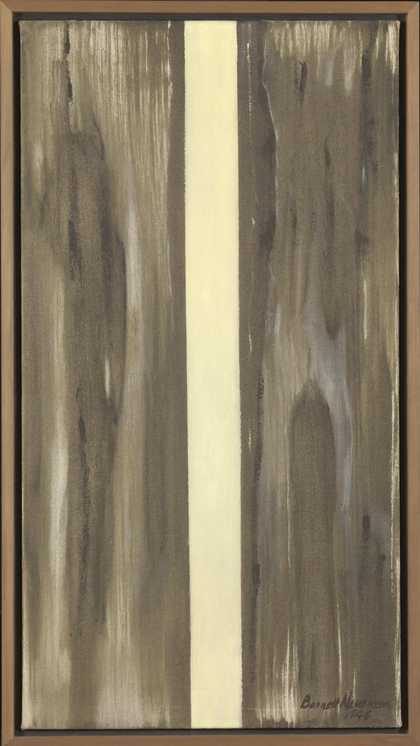

Newman was also responsible for one of the most distinctive and copied New York school compositional devices, the ‘zip’ (fig.2). This vertical spatial marker, which brought geometry to American painting, suggested ambiguous, psychological painterly dimensions. According to many, it was the sublime rendered on to the surface of the painting.5 Introduced in 1948, the zip helped to build the lore of mid-century mysticism that demarcated American abstraction as a special category for makers (like Newman) and supporters (like Alloway). The zip was an early indicator of Newman’s later painterly spirituality. In an essay published in 1971, Alloway remarked that with the zips in Newman’s Onement paintings, ‘myth is condensed into a primal form of high simplicity’.6 It was the element that drew Newman to the attention of younger minimalist sculptors, such as Donald Judd, who in 1970, the year of Newman’s death, described him as ‘the best painter’ in the country, owing to the pictorial wholeness achieved through the zips and the large scale of his paintings.7 Judd’s enthusiasm for Newman echoed his posthumous canonisation in the New York school, though Alloway thought Newman’s connection to Judd’s generation was due to their shared interest in writing. Certainly, this was Alloway’s interest in both of them.8

The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani held great significance for its curator. Newman and Alloway met in 1958, during Alloway’s first trip to the United States. Invited by the State Department, Alloway was a participant in the Foreign Leader Program of the International Educational Exchange Service during his tenure as the Deputy Director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London. His two-month tour from April to June 1958 took him from Washington D.C., Boston, Philadelphia and New York in the east, through Buffalo, Chicago, Cleveland and Detroit, to Denver, San Francisco, Los Angeles and San Diego in the west.9 In addition to the State Department’s rigorous schedule of visits to collections and meetings with institutional heads, such as Thomas Messer, then the director of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, Alloway had his own agenda. Selected by the Foreign Leader Program to promote cultural exchange and professional development, Alloway embarked on the trip to secure art loans from American institutions and to create new exhibition concepts.10

He insisted on seeing a great deal of architecture and requested introductions to Mies Van Der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright. He wanted to meet with two academics, the sociologist David Riesman and the rhetorician Kenneth Burke. Not surprisingly, Alloway called meetings with associates from his professional life as a critic, including his editor at ArtNews, Thomas Hess, and several art dealers. Artists were also of central concern for him. Gene Davis, Hans Hofmann, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still and others were marked on his itinerary by an asterisk as those with whom he requested an introduction. On his Chicago list Riesman, the artist Leon Golub and the dealer Allan Frumkin had double asterisks placed by their names, indicating that Alloway not only wanted to meet them but also that they would serve as local sponsors for him.

Alloway remained in New York for the longest stretch of the journey, and returned to the city at the end of the trip before departing for London. In a letter to his wife, the artist Sylvia Sleigh, written from New York, Alloway described a typical day in which he ‘had lunch with Rothko and saw his new pictures’ before meeting with the critic Harold Rosenberg, where he ‘questioned him about the term “Action Painting”’, while planning later visits with other artists including Hans Hofmann, Elaine de Kooning, Clyfford Still and Hedda Sterne.11 An invitation to the ‘The Club’ (‘where the artists meet every week or so’), and a few nights at the Cedar Bar (‘THAT bar where all the artists go’), cemented Alloway’s knowledge of the social life of New York artists.12 In New York, in addition to Rosenberg, Alloway met the art historian Meyer Schapiro and the critic Clement Greenberg. Greenberg was of special importance to Alloway, who was seen by peers, including the architectural critic Reyner Banham, as the only person in London ‘to keep abstract in front of the public nose’.13 To meet and befriend Greenberg in New York transformed Alloway from a peripheral fan to a major figure within the exclusive club of post-war art.14

While in New York, Alloway learned of Newman’s Bennington College retrospective from Greenberg, who had written for the exhibition catalogue. He then redirected his schedule to travel to Vermont to see the show with Newman’s dealer, Betty Parsons.

Last weekend I went to Bennington College — 200 miles from NY — in Vermont (the English area Magda recommended to you). Went by car with art dealer Betty Parsons, an English woman on Time Inc. (Rosalind Carter), [and] a southern woman painter … There was the 1st exh.[sic] in years of Barnett Newman. Wonderful great blank paintings — united with Still & Rothko. Clement Greenberg fixed the details for me.15

After returning to New York, Alloway met with Newman at his studio, where he saw paintings that would be included in The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani.16

Within days of this trip he wrote to Sleigh expressing his newfound comfort with abstract American art:

My first impression of NY art was, as I believe I reported, one of complete confusion. Now after seeing much of the work, talking to the people concerned (artists-dealers-collectors) I am getting it again — a less tidy but infinitely more real picture.17

Upon his return to London, Alloway spent the next two and a half years unpacking his American findings for the artists and writers around him, including John McHale and Reyner Banham, as well as the group of artists that he brought together for the Situation exhibition at the Royal Society of British Artists in 1960, all of whom had begun to work in the large scale then synonymous with American painting.18 The art critic Irving Sandler has documented how Alloway’s particular interest in Newman made its way into conversations with British artists in the 1950s who had not been to the States or seen Newman’s work in person.19 Moreover, in response to the gossip that surrounded The New American Painting – an exhibition that travelled from the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York to the Tate Gallery, London in 1959 – Alloway chided British critics for not embracing the show, calling the ‘New York School … art’s orthodoxy’.20

Alloway returned to the States in 1960 as a guest of Betty Parsons, who had invited him to stay with her to research and write An American Gallery, a monograph on her gallery and its relationship to post-war American art.21 By 1961, Alloway had relocated to the States to take a teaching job at Bennington College in Vermont.22 From there, he moved back to New York to become a curator at the Guggenheim, under the direction of Thomas Messer, whom he had met in 1958. In 1964, Alloway and Newman finalised a plan for an exhibition that became The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachthani. He had already situated Newman through the idea of systemic painting, declaring the paintings from 1958 ‘a saddle-point between art predicated on expression and art as an object’.23 By 1966 The Stations of the Cross was realised and Alloway was a known figure in New York as a curator, critic and teacher, and was asked to make local and national appearances to talk about art.

In the avalanche of press coverage that followed Alloway’s resignation from the Guggenheim in 1966 is an interview he gave in June that year to the critic Grace Glueck at the New York Times that reveals his prickly nature.24 In it he scolded New York museums for not showing enough recent art, called his own work (writing and curating) ‘short-term art history’ and gossiped about the Guggenheim’s inner workings, revealing that the Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim had been in aggressive competition for an exhibition of work by Robert Motherwell.25 Although Motherwell was his friend, Alloway was willing to reveal personal information about him in order to revel in the Guggenheim’s loss of Motherwell to MoMA.

The story of Alloway’s introduction to New York and its art, as it has been outlined here, provides a more general template for the ways in which an artist (in this case Newman), who was connected to a curator (Alloway) working in a museum (the Guggenheim), and who was financially tied to a series of individuals, had artworks circulating in the print media and in public exhibitions, and whose career rested on precariously intermingled professional and personal relationships. This is a template that could fit around any number of American artists active in New York from the late 1940s onwards. That I chose Newman to illustrate this model is incidental, save for the fact that Newman’s relationship to Alloway directly shaped it, for this is Alloway’s own template for the network of art and artists known as the ‘art world’.26 The artist turned magazine art director Alexander Liberman’s photograph of friends in his home – who were also clients, business associates and rivals – illustrates this network very clearly (fig.3).

Fig 3.

Photograph taken by Alexander Liberman of a gathering at his home c.1965 (from left to right: Lawrence Alloway, Tatiana Liberman, Barnett Newman, Sylvia Sleigh, Helen Frankenthaler (standing), Robert Motherwell and Annalee Newman)

© Alexander Liberman Photography Archive, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 2000.R.19

Photograph © Alexander Liberman

Although Alloway had for a long time been writing about specific roles for art workers and the many functions of art objects, his essay ‘Art and the Communications Network’ published in Canadian Art in January 1966 is likely to have been the first place that he specifically defined the conditions of the communications network. He began with this:

Art today is distributed in a network of communications more complex though not totally different in kind from the preceding five hundred years.27

Alloway found the noticeable differences between mid-century America and a larger international past to be twofold. First, there was the ability of the public to travel to see art, forming a circuit of travel with art as the destination; and secondly there was the facility with which art could be moved to be seen, such as travelling exhibitions or the loaning of art by museums and collectors. Through his role at the ICA and later the Guggenheim, Alloway had a wealth of experience with art as a fluctuating leisure commodity. The second distinguishing characteristic of the network of communications was something that he called the ‘visual explosion’, or the proliferation of reproduced images. The network that instigated the art/audience mobility consisted of the co-ordinated efforts of ‘Galleries, museums, books, magazines and biennial exhibitions’, with each playing a role in leveraging the new mobility of art or its facsimile.28

The visual explosion accounted for a third type of mobility, wherein the art object travelled as text, signage or in the guise of another object such as the picture of the op art dress published in Life magazine, a direct copy of a painting by the artist Bridget Riley.29 Many are familiar with the story of Riley’s attempt to sue the collector and manufacturer Larry Aldrich after he reproduced one of her paintings (that he owned) on fabric that was then turned into mass-market dresses.30 While that part of the story relates directly to Alloway’s citing of reproduction in the network, the circumstance of Riley’s visit to New York in 1965 is also an example of how art’s mobility functioned. She travelled from London for the opening of The Responsive Eye, William Seitz’s large-scale exhibition of optical art (or what he called ‘retinal’ art) at MoMA. Her work, by then in a number of private collections, was on loan for the show. Riley was at the event, but not for an express purpose such as, for example, to assist with the installation of her works. The exhibition included the work of over a hundred artists from fifteen countries, many of whom also came to the opening, along with their collectors and others interested in the spectacle that the exhibition promised. To this group can be added the director Brian de Palma’s documentary film of the show that subsequently became part of the network flow of its art and audience.31

‘Art and the Communications Network’ goes on to chart the movement of a work of art. The artwork starts its life in the artist’s studio or ‘work-place’, where it might be seen by a small audience before moving on to the commercial art gallery, a private collection, or a public collection.32 From either of the three transit hubs it will likely move into a museum exhibition, which will shape its entry into the ‘fourth context’, literature, in the form of exhibition catalogues, art magazine reviews or general interest magazine features.33 In each case, the diagnosis is not positive for the object, as it is ‘no longer substantially present as an object’ once the progression from studio to literature is enacted.34 For Alloway, the final stage represented a kind of flattening with the intrusion of literature. Within this progression, Alloway indicated the key players: art historians, curators, collectors, critics and dealers who, by acting out their specific role, incite a role-blurring as the need arose around the promotion of the art or the artist. Not surprisingly, the critic, or writer, has the most altered role at the mid-century because he or she is in the interpretative function of a speeded-up distribution cycle. Of this role, he remarked, ‘The typical strategy of an art critic today is to look for ways to reduce the quantity of art which the network handles so easily’.35

Alloway’s argument did not end here, nor did it move in the direction that it seemed to be heading, towards the conclusion that the network was a negative description of what art as a commodity had become. Instead, in the final passages of the essay, he recuperated the circulation brought by reproduction as one that instigated pluralism. If art was a ‘legible structure’, then reproductions were versions of the original that, in circulation and abundance, shore up the very real knowledge of that original. In the case of Riley, it may have been that Aldrich’s dress infringed on her intellectual property rights, but its circulation as a commodity brought wider public attention to the very thing it copied, her original painting. Similarly, the attention paid to The Responsive Eye encouraged other New York museums to replicate its success with their own international, media-savvy exhibitions, led by young, ambitious auteur-curators, such as Kynaston McShine’s Primary Structures at the Jewish Museum, which opened in April 1966, and Alloway’s Systemic Painting at the Guggenheim (fig.4), which opened in September 1966. This development further proves Alloway’s point about the importance of the museum exhibition in the life of an art object. Primary Structures sculptors Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd and Robert Smithson and Systemic Painting painters Agnes Martin, Kenneth Noland, Robert Ryman and Frank Stella also proved Alloway’s maxim that, ‘Museums now show not only new works but new talent’, constructing some of that talent pool for the institutions’ larger aims.36

Fig 4.

Lawrence Alloway (left) installing Systemic Painting at the

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 1966

Photograph by Robert E. Mates © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

The communications network, according to Alloway, was ultimately a useful force for ‘pluralist aesthetics’.37 This idea sounds like a late-modern mantra: more art is seen by more people in more ways, which means more artists can make more art. Here his use of the two-word term ‘communications network’ to describe the condition of new art in America shares an affinity with the critic Raymond Williams’s concept of communications or the communications industry, the plural form used to denote the action of information and ideas in what we would now call the media.38 Alloway’s use of terms to experience art is similar to Williams’s private dictionary of words with important historical transformations that was published in 1976 as Keywords.39

To read Alloway is to become immersed in a vocabulary shaped by the conditions of the twentieth century. Despite the reference to Keywords, it is not my intention to position Alloway as a Williams devotee. Rather, I am interested in the way that Alloway’s idea of the ‘communications network’ (later known simply as ‘network’), as a definition for art at a specific time that in turn identified a system (the art world), had the same goal as Williams’s re-purposing of ‘society’ into the more comprehensive term ‘culture’. That Alloway’s understanding of the term ‘network’ predated its widespread use as a description of the electronic age, and that it has since become a metaphor for all forms of interconnectivity, is all the more valuable. If Williams looked to history to situate culture, Alloway’s diagnosis of the network was ahead of its time.

While Alloway may not have been rehashing Williams, he was invested in the methods of sociology from which cultural studies grew in Britain. If we return to his first trip to America in 1958, and the requests for introductions that he made to the State Department, two stand out in a schedule otherwise dominated by art and architecture: David Riesman, the sociologist who was then at the University of Chicago, and Kenneth Burke, a rhetorician who was visiting the University of California at Berkeley.

These two meetings are important because they indicate where to situate Alloway’s use of sociological concepts, and the ways in which these two individuals represent specifically American approaches to cultural analysis. The culture of American art was, I would argue, what Alloway was focused on from a very early stage in his writing and curatorial practice. It is not just that Alloway was interested in American art, media and popular culture. He was invested in the art culture of America as it was being shaped in the middle of the twentieth century, and after 1962, when he emerged as one of the architects of that art culture.

In his book, The Lonely Crowd: A Study of the Changing American Character (1950), Riesman argued that America had three character types, but only one, the ‘other-directed’, was malleable enough to fit the new social roles necessitated by the modern world.40 The other-directed defined the middle class in industrialised America. In its ability to ignore tradition (be it familial or societal) in order to reap the benefits of the material abundance that modern society afforded, the American middle class was a flexible ‘peer-group’: it proved its usefulness in a corporate work system that rewarded it with more access to affluence.

A key symptom of the middle-class ‘peer-group’ was its internal maintenance (of behaviours, desires, expectations, abilities, goals etc.), something that Riesman called ‘antagonistic cooperation’.41 As Nigel Whiteley, author of a recent biography of Alloway, has noted, the British writer borrowed this term from Riesman to describe the ‘synthesis’ of competition and ‘complement’ that motivated the twelve teams that participated in the exhibition This Is Tomorrow at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, in 1956.42 Read and discussed by the Independent Group (IG) for its insight into American culture, Riesman’s ‘antagonistic cooperation’ suited the popular descriptions of the inter-workings of the IG, even if they sometimes seemed to favour one half of the phrase (antagonistic) over the other (cooperation).43 Perhaps The Lonely Crowd was a manual for how Alloway approached American art, artists and their critics during this first trip: a peer group with whom he would work collectively in the push and pull of ideas about art. What is, after all, the role of the curator if not a facilitator of the collaboration between artist and institution? Tellingly, after his turn at the Guggenheim, Alloway conceded curatorial friction, writing that ‘the curator is at the interface of the museum as an institution and the public as consumers’.44 Alloway held on to ‘antagonistic cooperation’ for a number of years, moving it into more nuanced discussions of art as opposed to relationships. In 1965, for example, it appeared in a discussion of the formal qualities of Jim Dine’s painting.45 In 1971, Alloway directly referenced Riesman in his book on film, Violent America: The Movies 1946–1964 and in a review of an exhibition of British art in New York that appeared in The Nation.46

Before Alloway’s proposed visit to Kenneth Burke in Berkeley, he saw buildings designed by the modernist architect Richard Neutra and visited Hollywood in Los Angeles, both products of the flexible-affluent America that Riesman described. Alloway had read Burke and was familiar with Burke’s statement on human motive, ‘dramatism’.47 In its most basic form, dramatism sought to identify human motivation. Core questions – what is happening, where is the act happening, who is involved in the action, how do the agents act, why do the agents act – were attached to five, one-word concepts: Act, Scene, Agent, Agency and Purpose.48 Used by actors to develop character skills, Burke’s five questions were taken up by theorists for application to any situation.

What Riesman and Burke seem to offer Alloway’s criticism is an approach to art in America as a system that needed to be seen inside its specific national conditions. In numerous interviews and recorded conversations in the 1950s, Alloway described his excitement about the art being made in America. While his feeling was not unique at the time, his expression that ‘new art is supposed to presage a new set of social values’ implied that he envisioned a social system taking shape around the art and its industry.49 When viewed from this perspective, his first trip to the States in 1958 appears like the investigation of a Burkian dramatism. With each meeting and in every new city, Alloway seemed to be asking: What is American Art? Where is it being made? Who is making it? Who else is involved? And what does everyone get out of it? The meetings with Riesman and Burke are significant, if only as a register of his interest in formulating a specific plan for America art. What this also suggests, however, is that by at least the spring of 1958 Alloway was looking for the thing that he would name in 1972: the art world.

In his essay, ‘Network: The Art World Described as a System’, first published in Artforum in 1972, Alloway gave his first description of the art world:

What does the vague term art world cover? It includes original works of art and reproductions; critical, historical, and informative writing; galleries, museums, and private collections. It is a sum of persons, objects, resources, messages, and ideas. It includes monuments and parties, esthetics and openings, Avalanche and Art in America.50

This expansion of the earlier network idea found in ‘Art and the Communications Network’ was re-presented as a fresh argument about the art world as a quantifiable entity of the 1960s. If the network described the present, ‘art world’ reshaped the history of the 1960s from the vantage point of the early 1970s. Alloway did not place the art world in New York because there was no need to. All of his references to artists, curators, exhibitions, institutions and magazines in the essay were specific to New York. Just as it was clear that the origins of the ‘fine-art-pop-art continuum’ rested on his understanding of a particular time and spirit in London (complete with a reliance on Williams’s concepts of culture and communication), the ‘art world’ is not only a metaphor for New York but also a synonym of it, expanding the idea of New York’s control over all American art to encompass its dominance of an international art market.51 To be engaged in the art world during that decade would have necessitated a relationship with New York in some form. Without New York, Alloway implied, there would be no art world. This idea feels very much like the Newman-Alloway story where Alloway fields a system with Newman’s objects while making a central place for himself within that system (New York, the Guggenheim, the Cedar Bar etc.).

By the time that ‘Network: The Art World Described as a System’ was published, Alloway was a leading figure in the art world. This may explain the change in tone from ‘Art and the Communications Network’, where the network was a more benign apparatus in service to the object. This article was written and published just before Alloway’s disagreement with the director of the Guggenheim, Thomas Messer, over the Venice Biennale that would end with Alloway’s resignation.52 Written later, ‘Network: The Art World Described as a System’ revealed Alloway as a seasoned citizen of the art world, one who saw it as a power structure on its last legs. The diaristic criticism that defined his writing from this point onwards affords pointed remarks about artists and names collectors who ‘pay high prices for new art, subject to elaborately negotiated discount’.53 He blamed collectors like John Powers, an early supporter of Newman, for attaching ‘the principle of conspicuous consumption’ to art.54 After announcing a crisis in art history that was both economic and methodological, he declared a shift in artists’ confidence and self-perception in the search for justice, be it the Art Workers Coalition or the protests against the Vietnam War. He concluded with the idea that ‘post-studio, site-based, and conceptual art forms’ were signs of stress that marked the 1960s turning into the 1970s. The art world was a 1960s thing that met its end with the downturn in the consumer market, the desire for artists to make objects that responded to a different set of circumstances, museums’ inability to reconceive themselves in relation to new art, and a general discontent with the gallery system. Both nostalgic and forward looking, Alloway called for artists in the 1970s to ‘make a real difference’.

How Alloway could forecast this shift in art culture with such precision is surprising, especially given that it is taken up only loosely by others in the decades that follow. Take for example, a review of Robert Morris’s Guggenheim retrospective in 1994 that saw the artist’s work as a response to the ‘velleities in the changing styles and movements that have dominated the contemporary art world over the past thirty years’, suggesting a firm locational or institutional frame for the art world.55 Writing about the role of the art critic, the Newsweek art critic Peter Plagens defined the art world as ‘the people directly and indirectly concerned with serious galleries, and museums that show recent and current art’.56 Since the early 1970s critic Lucy Lippard has situated the art world as a site of contention for women’s art. She stated that ‘a trialectic between the female world, the art world and the real world’ could be formed.57 Lippard’s utopian take positioned the art world as an aspirational sphere, one that might be achieved in a gender-balanced reconciliation with the real world. For the sociologist Howard Becker, the art world was a ‘network of people whose co-operative activity, organised via their joint knowledge of conventional means of doing things, produces the kind of art works that the art world is noted for’.58 In this circular logic, Becker’s art world is a space of production that produces the product of self. The locational veracity of the art world was also unquestioned by many. A sentence in Hal Foster’s book Return of the Real (1996) begins ‘Who in the academy or the art world’, implying a fixity for the art world on a par with another equally unreal real estate, the academy.59

While all of these examples treat the concept seriously, ‘art world’ is most often employed casually now to discuss the proliferation of art fairs, to differentiate between the serious and the frivolous pursuits of art, or to define some aspect of art lacking a sufficient definition. In its most flippant, parochial guise, the art world is what happens on many Thursday nights in Chelsea in New York. How did this term that had such historic and geographic specificity for Alloway, end up as the catchall gloss for the industry of contemporary art? How did it become negative and general, when it was intended as a specific critical analysis? Moreover, how did its meaning come to encompass everything and nothing at all about art?

Keywords, by definition, change meaning over time. While Alloway’s art world, network and system were modelled on his own experiences in New York in the 1960s with artists like Newman, he in no way owned these terms. Likely, he borrowed ‘art world’ from Arthur Danto who used it publicly as early as 1964. Danto’s ‘artworld’ (one word) sought to set up the pre-conditions for understanding the art object: ‘To see something as art requires something the eye cannot decry – an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an artworld.’60

This was a serious charge in the wake of such art as Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes, and it required a suspension of disbelief to enter into the art world to believe in the art object itself. Like Danto, Alloway used art world to define a spacio-temporal shift in objects and object-making. Unlike Alloway, however, Danto was less concerned with what that shift signified. That it signified was its purpose because there was no moratorium on Danto’s ‘artworld’. As Williams pointed out, words can morph in their time to have meanings at odds with other meanings. Our charge may be to take up their history and present use in Alloway scholarship, for which there has been very little until now. This process may open up discussions with real depth about the consequences of his writing. To see Alloway in Williams’s keyword model becomes one moment in a longer social and cultural history of the language of art.