An examination of two drawings in Tate’s collection by London-based artist David Musgrave (born 1973) prompts a consideration of what the medium of drawing can offer an artist today. Belonging to Musgrave’s Plane series of drawings, Plane with inverted figure 2007 and Folded plane no.2 2009 suggest, I shall argue, how artistry and illusionism may serve as vehicles for a conceptual investigation into the notion of objective truth. Musgrave aims to ‘unpick, dismantle and reconstruct appearance by using one of the most important support mechanisms for our idea of the real – objective representation.’1 He sees both mimetic and abstract images as products of the distorting and reconstructing techniques used to make both. ‘There is a sliding scale in my work from close resemblance to total invention which for me undermines any latent objectivity’, he has said. ‘Traditionally “correct” drawing is still a total falsification and transformation of the subject matter – I never see it as a “copy” of it.’2

Fig.1

David Musgrave

Plane with inverted figure 2007

Graphite on paper

630 x 503 mm

© David Musgrave

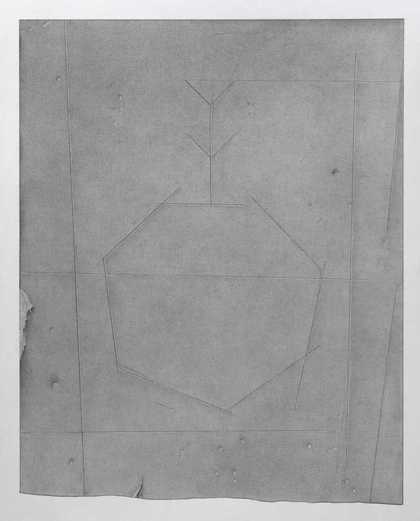

Plane with inverted figure 2007 (fig.1) shows an upside-down stick figure scored into card. Stick figures are typically used as a sign, a shorthand version of the real thing. This one, however, appears to have been carefully drawn, its legs neatly touching a horizontal line. The precision of the drawing undermines the casualness or brevity denoted by its character as a stick figure. If the work were untitled, would we see this figure? I think the answer is yes, because of our capacity to anthropomorphise the most basic lines and shapes. The lines that describe the figure do not sit on a blank, white sheet of paper: they appear incised rather than drawn, and the ground possesses a significant materiality, suggestive of stone rather than paper. This is because Musgrave’s maquette was made on greyboard, which has a soft, impressionable surface. Through careful use of graphite on paper he has rendered trompe l’œil pockmarks, tears and scuffs, creating an image of a distressed surface.

Fig.2

David Musgrave

Folded plane no.2 2009

Graphite on paper

515 x 430 mm

Tate

© David Musgrave

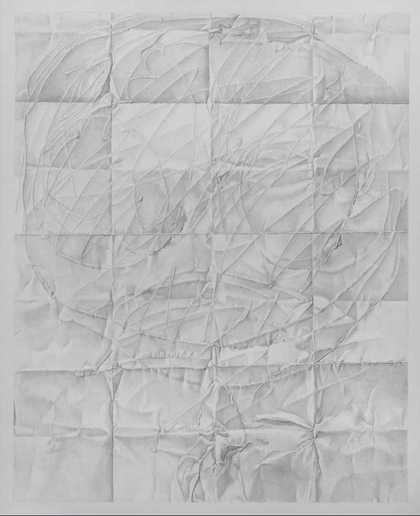

Folded plane no. 2 (fig.2) depicts a piece of paper that has been scored, folded, then crumpled, opened up again and smoothed out. The sparse, precise, geometrical lines of Plane with inverted figure have given way to multiple scribbled lines. And yet a ‘figure’, or at least a large circle, two smaller circles and an ellipse suggestive of a face can be deciphered, even if the torso and limbs are all but lost in the carefully depicted crumples. While the image is clearly hand-drawn, the hard graphite and use of blank paper work together to create an illusion of the folds and creases of the paper. The image is simple but also puzzling. Is it to be read as an invention of the artist’s or a copy of something pre-existing, a found piece of paper?

Fig.3

David Musgrave

Plane 2005–6

Graphite on paper

530 x 430 mm

Private collection

© David Musgrave

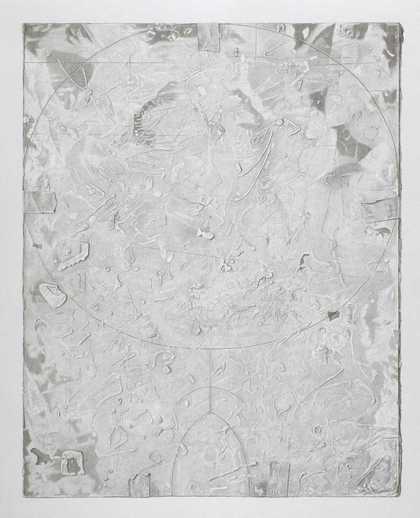

Other works in the series, which so far consists of around twenty drawings, are created through a combination of processes and it is this combination that distinguishes the series and Musgrave’s particular approach to making drawings. Musgrave does not begin with a particular image in mind that he duly executes using mimetic procedures. He begins by making a maquette or identifying a suitable object. This forms the starting point of the final drawing and a certain amount of its production involves careful observation and copying. However, it is the image unfolding on the paper that is of importance and improvisation and a combining of sources are employed to ensure its integrity. The first of Musgrave’s Plane drawings, Plane 2005–6 (fig.3) shows a surface encrusted with the sort of detritus that might cover an artist’s studio, table, floor or wall – squiggles of paint, bits of tape, splashes of liquid, evenly distributed. Over this textured surface is drawn a stick figure whose large head touches the top and sides of the image and whose legs finish at the bottom. Trompe l’œil pieces of tape appear to hold the image down. This drawing typifies the series, as it combines reproduction and invention and is not a straight copy of a maquette or found object.

Fig.4

David Musgrave

Plane with paper scraps 2006

Graphite on paper

476 x 378 mm

© David Musgrave

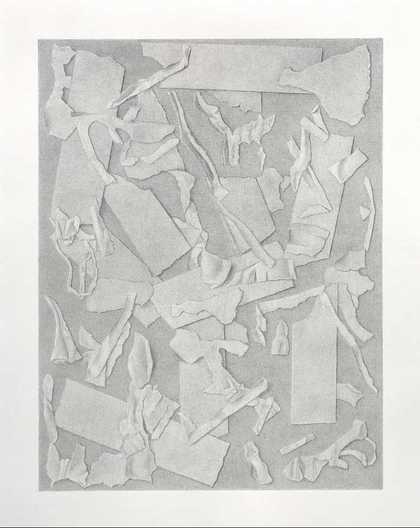

The title of Plane with paper scraps 2006 (fig.4) suggests that there is no figure to be found in the image, but the scraps form a circle in the upper half of the drawing and a vertical strip can be read as a torso. The fragments suggest the scattered bones of some creature, the care with which they have been torn and placed upon the plane somehow investing the arrangement with order and life.

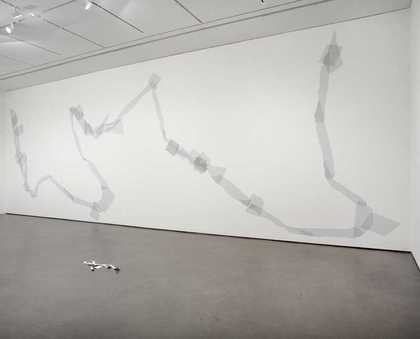

Fig.5

David Musgrave

Installation view of Art Now exhibition, Tate Britain 2003

Giant torn tape figure (grey) 2003 and Paper golem 2003

Courtesy greengrassi, London Photo: Tate

© David Musgrave

Musgrave has made a number of wall paintings that have similarly tested the boundaries of figuration. One of these is Giant torn tape figure (Grey) 2003 (fig.5), a wall painting made for a solo Art Now display at Tate Britain. The painting looked like a large meandering line made of masking tape, its association with the human figure all but eliminated by its huge scale. In fact, while the artist used masking tape to make the original small-scale figure, the final work was a trompe l’œil illusion. Musgrave explained, ‘I’m trying to push things to the point where the initial image is completely lost, and I wonder if it’s possible to embody the loss of an image in the making of an image. I want to hold on to the sense of the intention to depict something, even when circumstances make that extremely difficult’.3

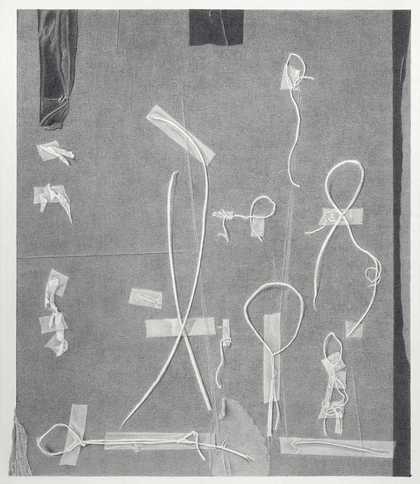

Fig.6

David Musgrave

Paper golem 2003

Aluminium and acrylic paint

830 x 415 x 55 mm

Courtesy greengrassi, London

© David Musgrave

Musgrave’s enquiry also led him to develop a series of sculptures from paper models. Paper golem 2003 (fig.6) is a sculpture made of aluminium and acrylic paint that lies on the floor. However, it looks like a rudimentary figure made from fragments of torn white paper that might waft away when we approach. It is one of a series of golems that were begun as maquettes made from torn paper or tape and were then manufactured in either painted aluminium or wood. Although insistently sculptural, these aluminium golem works have their origins in a single sheet of paper – a single plane – and their connection to drawing is therefore indisputable. ‘I tend to draw a clear line between my drawings and sculptures’, Musgrave has said, ‘but there’s always a moment at which their characteristics merge. Everything is an object, everything is an image’.4

While a rudimentary human figure is the subject of the majority of Musgrave’s drawings and wall paintings, it is generally only the sculptural works described above that carry ‘golem’ in their title (Paint golem no.1 and Paint golem no.2 from 2005 are drawings). In Jewish myth a golem is a figure made from river clay, into whose mouth was inserted a piece of parchment inscribed with the word shem – a Kabbalistic interpretation of God’s divine name – that animated the figure. Was the works’ move from two-dimensional sheets of paper to three-dimensional sculptures intended to convey a similar bringing to life? ‘I like to think that the beings that appear in my work inhabit [an] … intermediary zone between the animate and the inanimate. They live in the mind of the perceiver who, consciously or otherwise, invests them with life, but they can always revert to the status of raw objects’, Musgrave has said.5 Art critic Martin Herbert has suggested that all of Musgrave’s practice can be seen as related to the myth of the golem.6

Fig.7

David Musgrave

Plane with paper threads 2006

Graphite on paper

476 x 409 mm

Courtesy greengrassi, London

© David Musgrave

‘In making something’, Musgrave has said, ‘I think I’m always trying to embody the conditions that enabled that making to happen.’7 Musgrave feels ideas of immediacy and spontaneity in art are suspect. ‘You never make the first mark; there is always an archaeology or a history you can open up to a greater or lesser extent – sometimes a very specific history and sometimes a more general one.’8 Plane with paper threads 2006 (fig.7) plays with the notion of immediacy and spontaneity; it is easy to imagine how the scraps of paper just happened to fall into configurations that suggest the standing and prone figures that are roughly taped to the surface. Musgrave believes that artworks that are completely abstract struggle to communicate with the viewer at an emotional level. Our capacity to read the most rudimentary marks as representative of ourselves exists as a fundamental human trait. Musgrave’s oeuvre is characterised by an exploitation of this capacity and by an exploration of its limits: ‘His work is not, as some have suggested, predominantly an inquiry into anthropomorphism,’ Martin Herbert has observed, ‘except insofar as it spotlights a tendency to grab anthropocentric lifebelts while negotiating the rushing stream of an apparent abstraction’.9

As the descriptions of Musgrave’s sculptures and wall paintings make clear, his practice is not only devoted to drawing. This paper, however, considers why Musgrave chooses drawing as a means to produce his finished works. To answer this question we need to remind ourselves of the enquiry that underlines all of Musgrave’s artistic activity: how can a work of art address its material condition and simultaneously conjure an imaginary world or being?

Musgrave has widened the scope of his enquiry through curating exhibitions. Living Dust (2004), for example, was a show that featured works on paper from the sixteenth century to the present day.10 Works were chosen to demonstrate the transformative material capacity of the medium of drawing. Musgrave’s catalogue essay makes clear his frustration with the predominant conception of drawing as an expression of the artist’s intentions, thoughts and feelings.‘It’s rather the narrow but infinite gap between immaterial perception and its material recording that is their enduring content,’ he wrote.11 ‘Sometimes an image drifts so far from its referent that only its immediate context allows it to be identified […] what is significant [in such cases] is that the representation doesn’t become an abstract sign we subsequently use to communicate with others who recognise it, but something to be treated as having a particular, substantial reality of its own.’12

Drawing can be a slow, contemplative activity, something that happens quietly and that involves an interactive process. A mark is made, reflection ensues; more marks follow, with erasures, and slowly an image builds, is teased out of the paper. It is possible to create an illusion through drawing with graphite on paper but the medium’s monochromatic nature and the paper’s surface (something that Musgrave likes to work with rather than against) impose particular limitations. Musgrave employs trompe l’œil to create an illusion – but the uncertain status of the image draws attention to the methodology of production. Recourse to simple decoding tools, such as nameable things or a story line, are out of the question. Nonetheless, we somehow know what these things are, even if we cannot name them or attach labels to them. ‘I’d prefer the work to be seen to be about fiction rather than illusion’, Musgrave has said, ‘because I’m not trying to fool anybody. You can see how it’s done – if the fact that something isn’t what it appears to be doesn’t become part of the experience, then the work has failed.’13

Musgrave’s interest in unravelling the pretence of objective truth is one, of course, that he shares with many of his contemporaries. He emerged as an artist at a time when the American Robert Gober (born 1954) and the German Martin Honert (born 1953), were using artisanal methods and mimetic procedures to create work, primarily in three dimensions, that imitated everyday objects. Other artists who had a significant influence on Musgrave were LA-based artists Vija Celmins (born 1938) and Ed Ruscha (born 1937), both of whom pressed drawing into the service of mimesis in the early 1970s.

A return to figuration and the employment of more traditional, sometimes labour-intensive techniques allowed artists of Musgrave’s generation to rediscover drawing as a valid medium for making finished works. In 1969 the American conceptual artist Mel Bochner wrote an essay titled ‘Anyone Can Learn to Draw’. In this short text he attempted to unravel drawing’s then questionable status. He identified three principal modes of drawing: working, diagrammatic and finished. For Bochner, the first, as the ‘residue of thought’, was the most important, with finished drawings the least: ‘finished drawings don’t really have to be talked about in terms of drawing at all, but rather must be related back to the artist’s practice as a whole.’14 In other words, a finished drawing was equated with craft and manual dexterity, the importance of which conceptual artists of the 1960s were bent on undermining. Significantly, however, the techniques and rules of ‘finished drawing’ have been embraced by a number of artists since the early 1990s, as marked by the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition of 2002, Drawing Now: Eight Propositions. This exhibition included the work of twenty-six artists whose drawing practice is related to that of nineteenth century predecessors who favoured the polished, finished article over the working document. MoMA’s drawing survey exhibitions, the first of which took place in 1976, attempt to identify predominant tendencies in drawing. The work selected for the 2002 exhibition was described as ‘projective’ drawing, that is, depicting something that had been imagined before it was drawn. The MoMA exhibition followed a very particular trajectory in contemporary drawing, one that develops drawing’s long-established link to figuration and narration and places it at the service of an exploration of everyday life rather than the language of fine art.

It could be argued that Musgrave’s practice constitutes an exploration of the latter and that his finished drawings relish the containment that such finish might offer. His imagery resembles archaeological fragments or graffiti incised into stone, and his work can be seen as lying at an intriguing junction between those artists who use ‘finished’ drawing for descriptive and narrative purposes, as typified by the MoMA exhibition, and those who use ‘unfinished’ forms to explore political issues and abject states of mind, such as Los Angeles-based artists Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley.

Art historian Benjamin Buchloh has suggested that the history of drawing from the early twentieth century divides into two categories – matrix and grapheme. He uses the work of Jasper Johns to illustrate the model of drawing as matrix (‘Johns … denied the gestural trace any privileged access to function as an index of subjective experience’) and Cy Twombly the model as grapheme (‘[Twombly] precisely foregrounded the pure indexicality of the grapheme as subjective inscription in order to reveal to what extent the formation of subjectivity originated in the commonality of neuro-motoric and psychosexual impulses.’)15 For Buchloh the matrix model delivers an abstract form of the object, and the grapheme performs an abstract version of the subject. Between these two forms lies the palimpsest, essentially a flat ground scarred by erasure. It inhabits neither the world of the object nor that of subject but instead a ground whose scars suggest the passage of time.

What position would Musgrave’s Plane drawings occupy within Buchloh’s tripartite division of drawing modes? His Plane drawings present themselves as palimpsests, whose age-old surfaces are scarred by creases, scuffs, and tears wrought by supposedly intuitive acts such as scribbling, doodling, crumpling and folding. Yet the expressive scribbled lines of Folded plane no.2 also seem to incorporate the gestural mode of the grapheme. The viewer needs to pass through a number of cognitive stages to realise that a matrix mode of drawing has been used to create this artifice. Musgrave manages to invest a very shallow picture plane with an image of material density while avoiding the pitfalls of expressive inflection.

Since leaving art school in 1997 Musgrave has employed a number of techniques that incorporate a conceptual approach while embracing the material conditions of his works in two and three dimensions. He uses series of works to explore ideas that shift subtly between different manifestations, and most works involve multiple stages of production. Martin Herbert has suggested that Musgrave is, ‘by and large, a scientific realist – enlisting what something is not, or is no longer, to specify the essential quality of what it is now; and, most productively, to explore the various possible upshots of superimposing the two.’16 As Musgrave has said:

It’s the representation in its material aspect that I want to bring out, but not at the expense of a represented, re-imagined world, because there’s no ultimate fact involved (it never becomes ‘just’ graphite on paper, which is another sort of fantasy). I don’t think there’s an alternative to essentially faulty images – they’re how we build the world we inhabit. What I do is a way to try to live critically with that, but also find pleasure in it.17

Musgrave adopts an objective stance in relation to his methods of production; yet the subject matter is subjective, wrestling as it does with quite idiosyncratic preoccupations. It could be argued that while enacting a self-referential and analytical dialogue with the rules of traditional art forms, and particularly those associated with drawing, Musgrave’s ‘faulty images’ still perform an inter-subjective role. His interest is in enacting a cognitively satisfying dialogue with his viewers rather than serving up emotive gestures.