Some days ago I was working on this presentation when it occurred to me that I should check the time my talk was scheduled to begin. I was at my computer, so I entered ‘Edward Hopper’ and ‘Burgin’ into the Google search engine. I was given a link to the appropriate page of the Tate Modern website, but I was also directed to the website of The Star, a local newspaper in Shelby, North Carolina. There I read the following report:

Arrests Made in Cherryville Killing

CHERRYVILLE – Police arrested a Shelby man … and are looking for a Waco man in the shooting death of the owner of a N.C. Highway 150 poker parlor.

Johnny Thomas Mitchell Jr., 21, 102 Dakar Drive, Shelby, faces one count each of first-degree murder and robbery with a dangerous weapon. He is in Gaston County Jail without bond, and declined a request for an interview.

But police don’t think Mitchell was the person who shot Howard Ford ‘Sonny’ Neill Sr., 59, at his 2268 Highway 150 business. Cherryville Police Detective Sgt. Burgin said Edward Hopper, 24, of Edna Drive, Waco, shot the business owner after he and Mitchell robbed him.

Police contacted Hopper by phone and asked him to turn himself in, but he refused, Burgin said. Late Wednesday night they were still looking for Hopper …

Science fiction writers have posited parallel worlds closely similar to the world we know, but in which our counterpart selves pursue lives very different from our own. The story of Detective Sgt. Burgin in pursuit of a murderous Edward Hopper left me with the uncanny sense of such a world. But then there is a real sense in which the work of Edward Hopper constitutes a world parallel to our own: a latent presence in the interstices of the present.

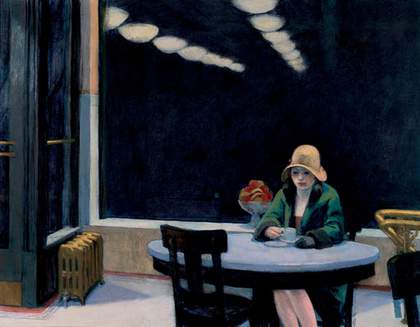

We need not look for Hopper in order to find him. We may encounter him by chance at random places where his world intersects our own. We might ask whether or not this photograph by the American documentary photographer Larry Sultan, was taken with Edward Hopper’s paintings consciously in mind. But the question is irrelevant. To know Hopper’s work is to be predisposed to see the world in his terms, consciously or not.

Fig.1

Larry Sultan

Sharon Wild, from the series The Valley 2001

Chromogenic print

Courtesy of the artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery, San Francisco CA © Larry Sultan

Fig.2

Edward Hopper

Hotel Room 1931

© Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. Madrid

Some years after I first exhibited my work US77, a friend remarked that this image reminded him of Hopper’s painting Night Windows. It had not occurred to me until he drew it to my attention.

Fig.3

Victor Burgin

US77 1977 (detail)

Courtesy the artist © Victor Burgin

Fig.4

Edward Hopper

Night Windows 1928

The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Gift of John Hay Whitney, 1940 © 2005, Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

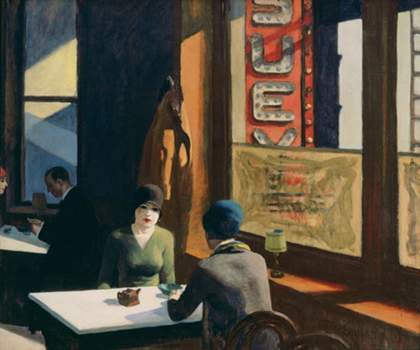

Just as I can be reminded of Hopper images on seeing images by other artists, so I can be reminded of the work of other artists when I look at Edward Hopper’s work.

The hackneyed idea of ‘influence’ is not at issue here. I am not interested in the question of what one artist may or may not have taken from another. I am referring to the universally familiar phenomenon of looking at one image and having another image spontaneously come to mind. The images that come to mind are not only such things as identifiable paintings or photographs, or particular images or scenes from films. They may also be more or less vague impressions to which we cannot assign any particular origin. To these belong the ‘fixed images’, the stereotypes of ‘commonsense’ that are the common coinage of mainstream media – popular journalism, television sitcoms, and so on.

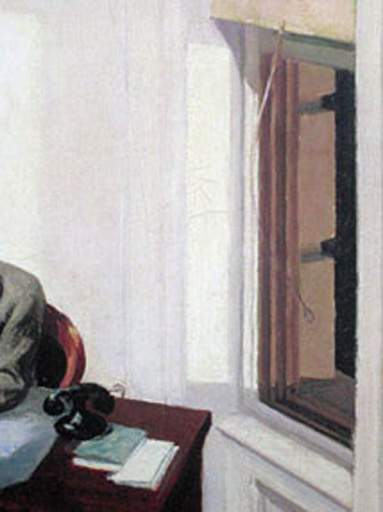

Fig.6

Edward Hopper

Office at Night 1940

Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Gift of the T.B. Walker Foundation, Gilbert M. Walker Fund, 1948

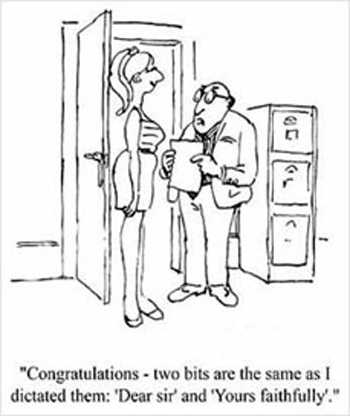

Hopper made extraordinary pictures of ordinary situations. Nothing is more ordinary a part of Western modernity than the office, and nothing more typical than the couple formed by secretary and boss. Hopper’s image of this couple may not bring any particular other image to mind, but it does suggest the kind of vague cliché situations hinted at in the original title that Hopper and his wife ‘Jo’ (the painter Josephine Nivison) gave to Office at Night: ‘Confidentially Yours, Room 1005’. To confirm for myself that the old stereotypes have survived into the age of the internet, having completed my search on ‘Hopper’ and ‘Burgin’, I made another search on the words ‘secretary’ and ‘boss’.

Fig.7

Fig.8

The cartoon is from the first of the websites on the list provided by Google. The photograph is from the second on the list of websites, one of several with names like ‘SecretaryBabes.com’. It is the first image in a pornographic narrative sequence. The stereotypical scenarios of secretarial incompetence and sexual impropriety are united in a recent film, Secretary, directed by Steven Shainberg and starring Maggie Gyllenhaal and James Spader (2002). The publicity synopsis of the film reads: ‘A young woman, recently released from a mental hospital, gets a job as a secretary to a demanding lawyer, where their employer-employee relationship turns into a sexual, sadomasochistic one.’ Both the screenplay and the short story on which it is based were written by women.1 Nevertheless the sexual politics of Secretary are cheerfully post-feminist. A sado-masochistic relationship in which the male boss inflicts physical and mental pain on his female employee is shown as a source of physical gratification and personal salvation for the woman.

The film Secretary post-dates feminist workplace and cultural activism of the 1960s and 1970s. Edward Hopper’s painting Office at Night, made in 1940, precedes this particular historical resurgence of feminism. No wind of change has yet blown through this office, although there is a strong breeze. I am reminded of the current that blows through such other Hopper images as, for example, his etching Evening Wind 1921. It is rarely fanciful to interpret Hopper’s ‘realism’ allegorically. The sudden current that disturbs here is as much sensual as meteorological. Perhaps it is the same evening wind that has blown a paper to the floor.

Fig.9

Edward Hopper

Office at Night 1940 (detail)

Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Gift of the T.B. Walker Foundation, Gilbert M. Walker Fund, 1948

Fig.10

Edward Hopper

Office at Night 1940 (detail)

Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Gift of the T.B. Walker Foundation, Gilbert M. Walker Fund, 1948

In the film Secretary, the woman returns the paper to her boss on all fours, with the document held between her teeth. Spontaneous associations between disparate images owe more to the dream-work than to the work of the historian. We should more responsibly refer Hopper’s Office at Night to the cinema of its own time. The cinema of Hopper’s time was self-governed by the 1930 Motion Picture Production Code, the so-called ‘Hays Code’. Section II, item 4, of the Hays Code states simply: ‘Sex perversion or any inference to it is forbidden’. The Hays Code was abandoned in 1967 after MGM released Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blow-Up, in spite of its having been denied Production Code approval.2 Hopper died that same year. The sexuality in Hopper’s images is that of the Hays Code era – one of inference, implication and innuendo.

His Private Secretary, directed by Phil Whitman and starring Evalyn Knapp and John Wayne, was released in 1936. A synopsis of the story reads: ‘The playboy son of a millionaire businessman falls in love with a secretary who is a minister’s daughter. The playboy’s father believes the girl is a gold-digger.’ What if the father is right about the girl? Sharing a double-bill with a romantic comedy there might have been a film noir. In the 1946 Otto Preminger movie Fallen Angel Linda Darnell plays a character called ‘Stella’. Stella reminds me of the secretary in Office at Night – the woman Hopper’s wife Jo called ‘Shirley’. Writing in The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, David Thomson describes Darnell as, ‘dark-eyed and sultry … one of the sirens of the 1940s whose rose-at-twilight looks seemed to stimulate every Fox cameraman’. Also starring in Fallen Angel was Dana Andrews, who, Thomson writes, ‘could suggest unease, shiftiness, and rancor … He did not quite trust or like himself and so a faraway bitterness haunted him.’

It seems to me that all Hopper’s men are haunted by a faraway bitterness, and Hopper’s women all have ‘rose-at-twilight’ looks. The summer wind blowing in at the window stirs them to leave their rooms. But even in youth and sunlight a twilight of age and experience falls on their features.

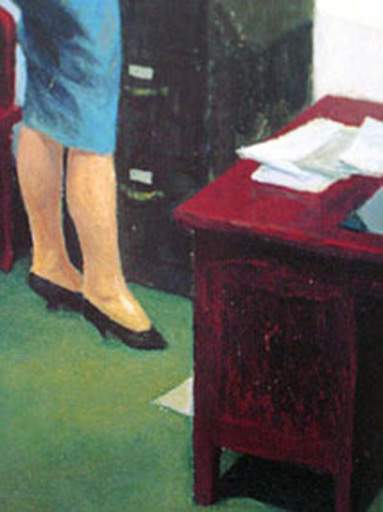

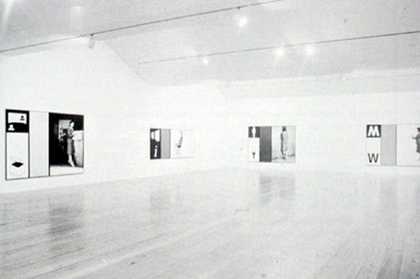

Fig.11

Victor Burgin

Office at Night, 1986

Installed in Knight Gallery, City of Charlotte, North Carolina, 1988

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal © Victor Burgin

Fig.12

Victor Burgin

Office at Night, 1986

Installed in Knight Gallery, City of Charlotte, North Carolina, 1988

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal © Victor Burgin

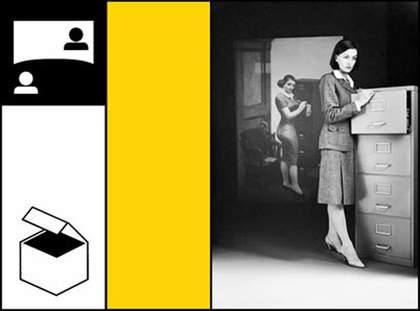

Fig.13

Victor Burgin

Section from Office at Night 1986 (detail)

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal © Victor Burgin

My own Office at Night was first shown at the ICA, London, in 1986. This image shows one of the sections from the seven-part photographic installation. I make no apology for having appropriated the title of Hopper’s painting. Hopper himself provided a precedent when he took the title for his painting Night Windows from a 1910 etching by John Soan, a painter he much admired.

In my book Between, which accompanied the exhibition, I speak of my work on Hopper’s painting as continuing a process of ‘re-viewing art through a prism of contemporary concerns’.3 The writer and filmmaker Laura Mulvey has referred to the year 1986 as the culmination of ‘a fifteen-year period that saw the Women’s Movement broaden out from a political organization into a more general framework of feminism’.4 My 1986 re-reading of Hopper’s 1940 painting was conducted within this framework.5 Here is what I wrote about Hopper’s Office at Night in Between:

Office at Night may be read as an expression of the general political problem of the organization of Desire within the Law, and in terms of the particular problem of the organization of sexuality within capitalism – the organization of sexuality for capitalism. Patriarchy has traditionally consigned women to supportive roles in the running of the economy, subject to the authority of men. The ‘secretary/boss’ couple in Hopper’s painting is at once a picture of a particular, albeit fictional, couple and an emblem, ‘iconogram’, serving to metonymically represent all such couples – all such links in the chains of organization of the (re)production of wealth. Such coupling for reproduction must of course contain its sexual imperative. The family functions to contain, restrain, this imperative in so far as it is directed towards the reproduction of subjects for the workplace. The erotic supplement to the biological imperative cannot however be contained in the family. It spills into the place of work, where it threatens to subvert the orders of rationalized production. [Hopper’s] painting, clearly, may represent such a moment of potential erotic disruption in appealing to such preconstructed meanings, items of the popular pre-conscious, as are filed under, for example, ‘working late at the office’. At the same time the painting stabilises the situation by providing a moral solution to the problem of the unruly and dangerous supplement. That the morality is patriarchal goes without saying.

Stability is made physically manifest in the massive formal stasis of this painting by a man who admired Courbet. Within a setting of firmly interlocking rectangles the main compositional device is a triangle, its base at the bottom edge of the frame and its apex at the head of the woman, making her the focal point of the image. From her head, our gaze is allowed unrestricted movement down the full length of her body. This body is twisted, impossibly, so that both breasts and buttocks are turned towards us. The body is ostensibly clad in a modest dress, but a dress which clings and stretches like a costume of latex rubber. An ambivalence similarly inhabits the woman’s gaze. Her eyes may be downcast, conventionally connoting modesty, or she may be directing a seductive or predatory look towards the man at the desk. This man does not return her look, his gaze is upon the strangely rigid sheet of paper in his hand. I’m reminded of Perseus, gazing into the shield which is about to reflect the image of the Gorgon. Clearly, if any impropriety were to take place here, then it would not be his fault. The painting therefore offers the heterosexual male viewer, by identification with the man in the image […] the exciting promise of a forbidden satisfaction without blame attached. The elaborately constructed alibi pivots on a disavowal of voyeurism: ‘I (male spectator) know very well that I am looking at the body of this woman, but nevertheless I (imaged man) am not.’ The painting offers itself as evidence in his defense, like a photograph presented in a court of law.

There is another way in which her gaze might be interpreted. Her look might be directed towards the paper lying on the floor. We can just see the corner of it, appearing from behind the left-hand side of the desk. It is the only thing out of place in this otherwise orderly scene. If we were watching a film, we might have witnessed someone drop this paper. But we are looking at a still image, and we do not know [who or what] is responsible for its being there. The fallen paper renders the space between the woman and the man disorderly. It is an unruly element in their relationship. In both spatial compositional terms, and in implicit narrative terms, the painting hinges around this point. This is not a film, and the absence of any explicit causality gives a narrative ambiguity to the image. We might suppose the woman has dropped the paper. We only see a corner of it, and this small triangular shape may suggest the handkerchief the woman drops, according to popular tradition, as a preliminary seductive maneuver (as Freud remarks, it may take a great deal of activity to achieve a passive aim). Or perhaps it is the man who has dropped the paper. Without deigning to notice it, he will wait for her to return it to him. Here the scene is sadomasochistic in implication, and of course it can be played with the roles reversed – with the woman as dominatrix. Or again, perhaps the paper has fallen unnoticed from his desk. Finding it gone he will turn to search for it, but she will already have dropped to one knee to retrieve the document. She will offer him the paper, but the significant exchange will take place when their eyes meet. Many scenes may be played upon this fantasy stage, in this office at night. But a reality under the rule of law will always intervene to cut the narrative threads which unwind from this image, which threaten to unravel the seamless weave of the social order. What Lacan calls the endless ‘sliding of the signified under the signifier’ has to stop in the name of the Law. What better agency to put a stop to this play than the agency which set the play in motion, the agency of vision, but now in its positivist, empiricist, mode: ‘See for yourself … nothing improper is happening here.’

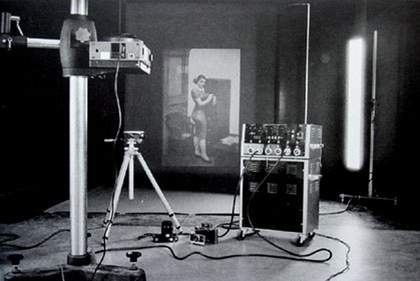

Fig.14

Studio during the shooting of Office at Night, 1986

Fig.15

Victor Burgin

Section from Office at Night 1986 (detail)

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal © Victor Burgin

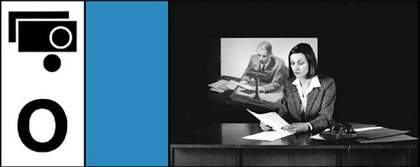

Fig.16

Victor Burgin

Section from Office at Night 1986 (detail)

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal © Victor Burgin

My point of departure for the photographic work I made in 1986 was the position of the woman in Hopper’s painting. The woman in the painting is there to be looked at, an object of sexual curiosity.

My aim was to transform the role of the woman from object of curiosity to that of subject of curiosity – to transform showing into knowing, exhibitionism into epistemophilia. In an interview recorded at the time of my ICA exhibition, I described my own Office at Night in the following terms:

The office in Hopper’s painting is a very enclosed space. Most of the elements in my piece are derived from elements within that space. The fantasy is that the woman explores the space of Hopper’s painting, appropriates that space for herself. The pictograms [are] added as a counterpoint, in a sort of ‘möbius strip’ action – in that the pictograms refer to the inside of the office, wrapping around that enclosed space, but at the same time are continuous, in formal and thematic terms, with what’s happening outside the office. I thought of the ubiquitousness of that sort of symbol system in the contemporary environment: Walk/Don’t Walk; Stop; No Entrance; Passport Control. It’s the very index of the omnipresence of control, authority. For me, the pictograms serve as a sort of analogue of the universe surrounding the office.

Before I made my work based on Office at Night my interest in issues raised in feminist writings had led me to make other works in which I cited well-known paintings of women.

This is a detail from my work Olympia 1982. Apart from the obvious allusion to Manet, the work also makes reference to Alfred Hitchcock’s film Rear Window, and to E T. A. Hoffman’s story ‘The Sand-Man’.

Fig.17

Victor Burgin

Olympia 1982 (detail)

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d'art moderne, Paris © Victor Burgin

Below are details from my work The Bridge, 1984. The work both refers to Sir John Everett Millais’s well-known painting of the drowned Ophelia and cites Alfred Hitchcock’s film Vertigo.

Fig.18

Victor Burgin

The Bridge 1984 (detail)

Fond Nationale d'Art Contemporain, Paris © Victor Burgin

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt

Ophelia (1851–2)

Tate

Fig.20

Victor Burgin

The Bridge 1984 (detail)

Fond Nationale d’Art Contemporain, Paris

© Victor Burgin

In these earlier works, citation took the form of a single image inserted into an image sequence that contained little or no other reference to the painting. The need to make the reference clear in a single photograph necessitated a relatively high degree of fidelity to the original painting.

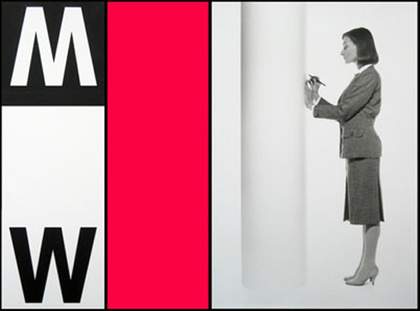

In approaching Hopper’s Office at Night I devoted the entire image sequence to the painting. This relaxed the constraints of mimetic reconstruction and allowed more latitude for deconstruction. I began by redefining Hopper’s work to include both the painting and the preparatory drawings. My own piece was based on this composite body of work rather than the painting alone. For example, my allusion to the figure of the secretary owes more to the drawings than to the painting.

From the drawings I also retained the idea of a picture on the wall behind the figures, using this space for direct quotation of Hopper’s painted secretary and boss. The explicit mobility of the secretary in my work is implicit in Hopper’s painting. For example, the desk in the foreground of the painting suggests a place of movement between desk and filing cabinet. Or again, what remains constant throughout all the drawings and the painting is the open door on the left – another place of transition.

Fig.21

Victor Burgin

Section from Office at Night, 1986 (detail)

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal © Victor Burgin

In each of the seven sections of my work, the woman is seen with one or other of the material objects that make up the object world of Hopper’s Office at Night. In addition to these physical objects there are graphic pictograms alluding to objects and object-relations. Unlike the graphic signs familiar from the everyday environment, these give no clear directions. They ambiguously imply commentary or narrative development. The woman’s gesture in this section is that of ‘bracketing out’ the person on the other end of the line. A brackets sign appears in the lower left; at the upper left it is rotated through 90 degrees and the circular form of the telephone mouthpiece reinstated – the resulting pictogram suggests an eye. Vision and audition, voyeurism and eavesdropping – for the Lacanians here, the scopic and invocatory drives.

Fig.22

Victor Burgin

Section from Office at Night 1986 (detail)

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal © Victor Burgin

Fig.23

Victor Burgin

Section from Office at Night 1986 (detail)

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal © Victor Burgin

The simplified colour-space characteristic of Hopper’s paintings is abstracted from the figurative image and schematically rendered in terms of the four ‘official’ colours used in the international signage system.

There is no allusion to the work of Caspar David Friederich in Hopper’s Office at Night, but such implications may be found elsewhere in Hopper’s work. I had believed that this was my own discovery, until I found such comparisons made in the catalogue essays. My allusion to Joshua Reynolds’s Portrait of Mrs Lloyd was strictly speaking gratuitous, as there is no evidence that Hopper had any interest in this painter’s work.

The characteristics of the space through which the figure moves in my work is derived not only from Hopper’s Office at Night but from the spatial attributes of his work in general. Hopper’s pictorial space is that of nineteenth-century theatre, and most of the Hollywood cinema of his time. In its simplest definition it consists of a décor (usually shallow, and arranged more or less parallel to the picture plane), to which a figure may be added. Objects may be placed with the figure. These usually serve to steer the narrative implications of the image, or to identify the type of space depicted. Hopper’s space is a contingent assembly of place-holders for things and for people recently arrived or about to move on. I think, for example, of his painting Hotel Window 1955: a body bracketed in a couch in a hotel lobby in a street – a parenthetical aside in an incomplete sentence.

Hopper paints the separateness of things: the indifference of objects, the solitariness of people, the isolation of the onlooker. This is the order of things in Hopper’s parallel world. When I look back now to my work of 1986, in which I looked back to Hopper’s work, to Hopper’s world, I find the same order of things, the same separateness of things, in my works from the intervening years – works which in appearance seem to have nothing in common with Hopper. For example, in the video work Nietzsche’s Paris, first shown in 2000, the figure is separated from the space in which the camera searches for her, and her words are separated from her in a third space. I first shot the panoramas that form the basis of that work as ‘live’video. I then removed the live motion, removed the colour, and finally removed the figures.

Fig.24

Victor Burgin

Nietzsche's Paris 2000

Video still

© Victor Burgin

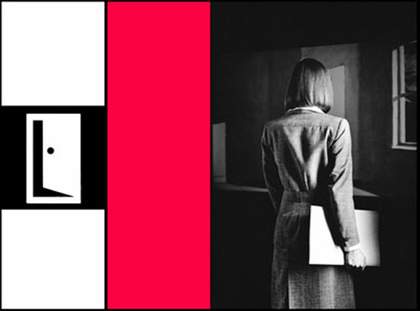

Fig.25

Victor Burgin

Section from Office at Night 1986 (detail)

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal © Victor Burgin

In the left-hand side of Hopper’s Office at Night is an open door. The woman has left the office and now stands in an empty room. The room was painted by Edward Hopper in 1963. The painting is called Sun in an Empty Room. In her essay in the Hopper exhibition catalogue, Sheena Wagstaff notes that Hopper ‘had originally added a figure to a sketch for Sun in an Empty Room … which he subsequently removed’.

Hopper died in 1967, the year I left Yale University School of Art and Architecture. Hopper was not on my mind that year. My teachers at Yale had included Robert Morris and Donald Judd. Morris had said that he wanted his sculptures to be no more or less important than any other of the ‘terms’ in the room in which they were situated. But I had asked him the question: if his sculpture was to be considered no more worthy of attention than the doors, the floor, the windows, and so on… then why not dispense with the art object altogether? Judd had said that a form that was neither geometric nor organic would be a great discovery. It seemed to me that such a form did not exist in the material world but could only be found in the mental realm. By the time I left Yale I was trying to find a way of dispensing with the material object, a way of leaving the room empty. I later learned that some other artists of my generation were working on similar problems. In 1969 we were gathered together in the show When Attitudes Become Form, the first international exhibition of what became called ‘conceptual art’ – work which had very little in common with what goes by that name today.

I began with a story of the police after Hopper. In his essay contribution to the catalogue for the Edward Hopper exhibition, Hopper’s friend Brian O’Doherty writes: ‘When I asked [Hopper] a question about what he was after in Sun in an Empty Room, [he responded], “I’m after ME”.’6

Some three years before Hopper made Sun in an Empty Room, the painter Philip Guston recalled:

John Cage …once told me, ‘When you start working everybody is in your studio – the past, your friends, enemies, the art world, and above all, your own ideas – all are there. But as you continue painting, they start leaving, one by one, and you are left completely alone. Then, if you are lucky, even you leave.7