Edward Hopper belongs to a particular category of artist whose work appears sad but does not make us sad – the painterly counterpart to Bach or Leonard Cohen. Loneliness is the dominant theme in his art. His figures look as though they are far from home. They stand reading a letter beside a hotel bed or drinking in a bar. They gaze out of the window of a moving train or read a book in a hotel lobby. Their faces are vulnerable and introspective. They may have just left someone or been left. They are in search of work, sex or company, adrift in transient places. It is often night, and through the window lie the darkness and threat of the open country or of a strange city.

Yet despite the bleakness Hopper’s paintings depict, they are not themselves bleak to look at – perhaps because they allow us as viewers to witness an echo of our own griefs and disappointments, and thereby to feel less personally persecuted and beset by them. It is sad books that console us most when we are sad, and the pictures of lonely service stations that we should hang on our walls when there is no one to hold or love.

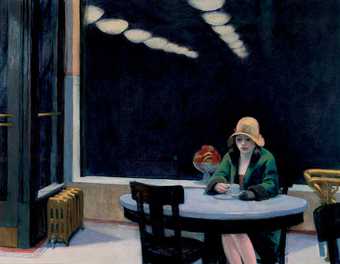

In Automat 1927, a woman sits alone drinking a cup of coffee. It is late and, to judge by her hat and coat, cold outside. The room seems large, brightly lit and empty. The décor is functional, with a stone-topped table, hard-wearing black wooden chairs and white walls. The woman looks self-conscious and slightly afraid, unused to being alone in a public place. Something appears to have gone wrong. She unwittingly invites the viewer to imagine stories for her, stories of betrayal or loss. She is trying not to let her hand shake as she moves the cup to her lips. It may be eleven at night in February in a large North American city.

Automat is a picture of sadness – and yet it is not a sad picture. It has the power of a great melancholy piece of music. Despite the starkness of the furnishings, the location itself does not seem wretched. Others in the room may be on their own, men and women drinking coffee by themselves, similarly lost in thought, similarly distanced from society: a common isolation with the beneficial effect of lessening the oppressive sense within any one person that they are alone in being alone. Hopper invites us to feel empathy with the woman in her isolation. She seems dignified and generous, only perhaps a little too trusting, a little naïve – as if she has knocked against a hard corner of the world. The artist puts us on her side, the side of the outsider against the insiders.

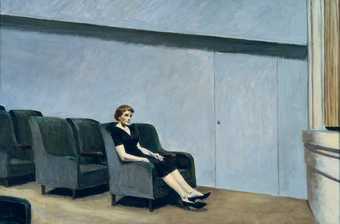

Edward Hopper

Intermission 1963

Oil on canvas

101.6 x 152.4 cm

© Collection of Mr and Mrs R. Crosby Kemer Jnr

Edward Hopper

Hotel by a Railroad 1952

Oil on canvas

79.4 x 101.9 cm

© Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC; Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation

In roadside diners and late-night cafeterias, hotel lobbies and station cafés, we too may dilute a feeling of isolation in a lonely public place and hence rediscover a distinctive sense of community. The lack of domesticity, the bright lights and anonymous furniture, may be a relief from what can be the false comforts of home. It may be easier to give way to sadness here than in a living room with wallpaper and framed photographs, the décor of a refuge that has let us down. The figures in Hopper’s art are not opponents of home per se; it is simply that, in a variety of undefined ways, home appears to have betrayed them, forcing them out into the night or on to the road. The 24-hour diner, the station waiting room or motel are sanctuaries for those who have, for noble reasons, failed to find a place of their own in the ordinary world.

A side-effect of coming into contact with any great artist is that through their work we start to notice things we can understand, but previously hadn’t thought worthy of consideration. We become sensitised to what one might call the Hopperesque, a quality now found not only in Hopper’s North American locales, but anywhere in the developed world where there are motels and service stations, roadside diners and airports, bus stations and all-night supermarkets. Hopper is the father of a whole school of art that takes as its subject matter threshold spaces, buildings that lie outside homes and offices, places of transit where we are aware of a particular kind of alienated poetry. We feel Hopper’s presence behind the photographs of Andreas Gursky and Hannah Starkey, the films of Wim Wenders and the books of Thomas Bernhard.

Hannah Starkey

Untitled 1998

C-type print

122 x 152 cm

Courtesy Maureen Paley Interim Art © Hannah Starkey

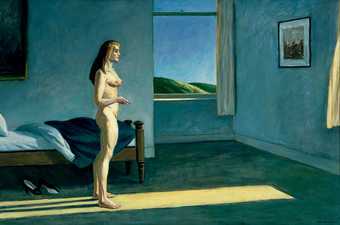

Edward Hopper

A Woman in the Sun 1961

Oil on canvas

101.6 x 152.4 cm

50th Anniversary Gift of Mr and Mrs Albert Hackett in honour of Edith and Lloyd Goodrich © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

I remember finding the Hopperesque one evening in a service station off the motorway between London and Manchester. Objectively speaking, it wasn’t a beautiful building. The lighting was unforgiving, bringing out pallor and blemishes. The chairs and seats, painted in childishly bright colours, had the strained jollity of a fake smile. No one was talking, no one admitting to curiosity or fellow feeling. We gazed blankly past one another at the serving counter or out into the darkness. We might have been seated among rocks. I sat in a corner, eating fingers of chocolate and taking occasional sips of orange juice. I felt lonely, but, for once, this was a gentle, even pleasant kind of loneliness. Rather than unfolding against a backdrop of laughter and fellowship, in which I would suffer from a contrast between my mood and the environment, this loneliness emerged in a place where everyone was a stranger, where the difficulties of communication and the frustrated longing for love seemed to be acknowledged and brutally celebrated by the architecture and lighting.

Edward Hopper

Gas 1940

Oil on canvas

65.6 x 100 cm

© 2003, Digital Image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

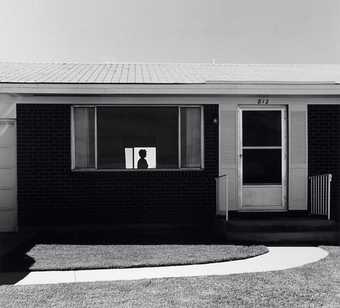

Robert Adams

Colorado Springs, Colorado 1968

Photograph

28 x 36 cm

© Courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Service stations always evoke for me Hopper’s Gas 1940, painted thirteen years after Automat and, like the earlier picture, also a study of isolation. A petrol station stands on its own in the impending darkness. But in Hopper’s hands, the isolation is again made poignant and enticing. The darkness that spreads like a fog from the right of the canvas, a harbinger of fear, contrasts with the security of the building. Against the backdrop of night and wild woods, in this last outpost of humanity, a sense of kinship may be easier to develop than in daylight in the city.

It’s a curious feature of Hopper’s work that although it seems concerned to show us places that are transient and un-homely, we may, in contact with it, feel as if we have been carried back to some important place in ourselves, a place of stillness and sadness, of seriousness and authenticity: it can help us to remember ourselves. How is it possible to forget ‘oneself’? At stake is not a literal forgetting of practical data, rather a forgetting of those parts of ourselves with which a particular sense of integrity and well-being appears to be bound up. We have many different selves, not all of which feel equally like ‘us’ – a division we confront most clearly in relation to our physical appearance. We may judge that the person a photographer has captured, while having something to do with the being bearing our name, in fact has very little connection with the spirit and attitude we would choose to identify with. This visual dynamic has a psychological equivalent within our own minds: we are made aware of constellations of ideas and moods distinct enough to feel like different personalities – an inner fluidity which can on occasion lead us to declare, without any allusion to the supernatural, that we are not feeling as if we are ourselves.

On looking at a picture, we may recognise it as important to us, but out of our ordinary reach. By buying a postcard reproduction and hanging it prominently above the desk (as I have done with a number of Hopper’s works), we may be trying to have it as an omnipresent, solid token of the emotional texture of the person we want to be and feel we are deep down. By seeing the picture every day, the hope is that a little of its qualities will rub off on us. What we may welcome isn’t so much the subject matter as the tone; it is the record of an emotional attitude conveyed through colour and form. We know we will of course drift far from it – that it won’t be possible or even practical to hold on to the picture’s mood forever, and we will have to be many different people (with bold opinions and a sense of certainty, with casual wit and parental authority) – but it is a reminder and an anchor that will tug us back to the qualities within it.

Hopper also took an interest in cars and trains. It is a pity he didn’t live long into the jet age, though we sense his shadow in many contemporary works. The artist was drawn to the introspective mood that travelling seems to put us into. He captured the atmosphere in half-empty carriages making their way across a landscape: the silence that reigns inside while the wheels beat in rhythm against the rails outside, the dreaminess fostered by the noise and the view from the windows – a dreaminess in which we seem to stand outside our normal selves and have access to thoughts and memories that may not emerge in more settled circumstances. The woman in Hopper’s Compartment C Car 293 1938 seems in such a frame of mind, reading her book and shifting her gaze between the carriage and the view.

Edward Hopper

Compartment C, Car 293 1938

Oil on canvas

50 x 45 cm

Photograph © Geoffrey Clements/Corbis

© Private collection

Few places are more conducive to internal conversations than a moving plane, ship or train. There is an almost quaint correlation between what is in front of our eyes and the thoughts we are able to have in our heads: large thoughts at times requiring large views; new thoughts, new places. Introspective reflections that are liable to stall are helped along by the flow of the landscape. The mind may be reluctant to think properly when thinking is all it is supposed to do. This can be as paralysing as having to tell a joke or mimic an accent on demand. Thinking improves when parts of the mind are given other tasks, are charged with listening to music or following a line of trees. The music or the view distracts for a time that nervous, censorious, practical part of the mind that is inclined to shut down when it notices something difficult emerging in consciousness and runs scared of memories, longings or original ideas, preferring instead the administrative and the impersonal.

Edward Hopper

Hotel Room 1931

Oil on canvas

150 x 162.5 cm

Photo: Francis G Mayer/Corbis © Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

Of all modes of transport, the train is perhaps the best aid to thought: the views have none of the potential monotony of those on a ship or plane. They move fast enough for us not to get exasperated, but slowly enough to allow us to identify objects. They offer us brief, inspiring glimpses into private domains, letting us see a woman at the moment when she takes a cup from a shelf in her kitchen, before carrying us on to a patio where a man is sleeping and then to a park where a child is catching a ball thrown by a figure we cannot see.

At the end of hours of train-dreaming, we may feel we have been returned to ourselves: that is, brought back. Hotels offer a similar opportunity to escape our habits of mind, and it is unsurprising that Hopper painted them repeatedly – Hotel Room 1931, Hotel Lobby 1943, Rooms for Tourists 1945, Hotel by a Railroad 1952, Hotel Window 1955 and Western Motel 1957. Lying in bed in a hotel, the room quiet except for the occasional swooshing of an elevator in the innards of the building, we can draw a line under what preceded our arrival. We can overfly great and ignored stretches of our experience. We can reflect upon our lives from a height we could not have reached in the midst of everyday business – subtly assisted in this by the unfamiliar world around us: by the small wrapped soaps on the edge of the basin; by the gallery of miniature bottles in the mini-bar; by the room-service menu with its promises of all-night dining and the view on to an unknown city stirring silently 25 floors below us. Hotel notepads can be the recipients of unexpectedly intense, revelatory thoughts, taken down in the early hours.

If a feature of love is an overcoming of loneliness, it is only fitting that, a few weeks after we met, my now-wife and I realised that we shared a love of alienated Hopperesque spaces and, in particular, of Little Chef restaurants.

Little Chefs are to British life what the diner is to America: ugly places full of bad food that are nevertheless resonant with poetry. My wife had been taken to Little Chefs as a young girl by her father, a man of few words who liked to order an English breakfast, read the paper and gaze out of the window smoking a cigarette. It had felt like a break from routine, from the monotony of growing up in a dull Suffolk market town. The menu was bright, someone brought you the food to your table and there might be a slide to play on outside. She had always gone for the Jubilee pancakes and once on her birthday had had two orders and been sick all over the back of the family car. Then, at university, Little Chefs had been a place to go to when she wanted to get away from the hot-house atmosphere of her campus and see more ordinary life roll by for a while.

For my part, I remembered going to Little Chefs with my parents as a rare treat – or funerary rite – before returning to boarding school. It was a symbol of a multi-coloured, warm cheerful world that I wanted to hang on to forever, so vivid was its contrast with the place I was headed for. Then, grown up, in a long and sometimes painfully lonely period in my mid-twenties, I’d sometimes drive out of London to have a solitary lunch in a Little Chef. It felt comforting to drown my own alienation in a wholeheartedly alienated environment. It felt like reading Schopenhauer when one is down.

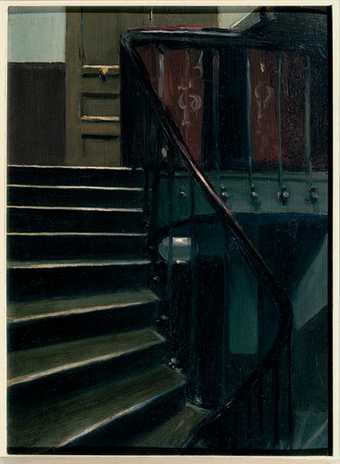

Edward Hopper

Stairway at 48 rue de Lille, Paris 1906

Oil on wood

33 x 23.5 cm

© Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Josephine N. Hopper Bequest

Little Chefs are in many ways about loneliness; about a particularly English kind of loneliness even. They both represent and are a curious cure for it. Thanks to the unlikely setting of a Little Chef, we can for a time escape some of the constraints of home, of our habits of mind, of the rules of sophisticated society – and enjoy a beguiling vision of an alternative life. To identify a common taste in Little Chefs doesn’t just mean sharing a taste in restaurants, it means sharing a piece of inner, very private psychology. It’s a wonder they don’t hold more wedding parties there.

Oscar Wilde once remarked that there had been no fog in London before Whistler had painted it. There was, of course, lots of fog, it was just that little bit harder to notice its qualities without the example of Whistler to direct our gaze. What Wilde said of Whistler, we may well say of Hopper: that there were far fewer service stations, Little Chefs, airports, trains, motels and diners visible in the world before Edward Hopper began painting.