When Matta-Clark installed Walls Paper (Tate T14658) at 112 Greene Street in New York 1972, he did so in conjunction with his earliest ‘building cuts’ – fragments of architecture he extracted from existing buildings. One of these was a wall segment from Food, the restaurant located just one block away from 112 Greene Street that Matta-Clark had recently renovated with artist and dancer Carol Goodden, his partner during these years. As Goodden later recalled of the intermingling of wall cut-outs and Walls Paper:

This was the beginning of his cutting houses; cutting whole houses came right after this cutting of sections of floors … he never was as interested in the pieces as he was in the hole. The light and the lines interested him much more than the piece, which was simply documentation. He was taking something that was dead-looking and making it alive again.1

Goodden saw the works as a reactivation, a way of enlivening the forgotten spaces of New York City. Food arose from a similar, if more concrete, desire. The restaurant’s establishment preceded Walls Paper by one year, but their intermingling in the gallery at 112 Greene Street demonstrates the spectrum of methods Matta-Clark was using to activate urban spaces. This is how we know that Walls Paper is more than a romantic documentation of dilapidated buildings around the city – Food’s creation exemplified the ways in which communal do-it-yourself efforts could have a positive socio-economic impact on a neighbourhood. By exhibiting Walls Paper in the same visual field as building fragments from Food, Matta-Clark’s exhibition pointed to both sides of the urban predicament: decay and renewal.

The genesis of Food

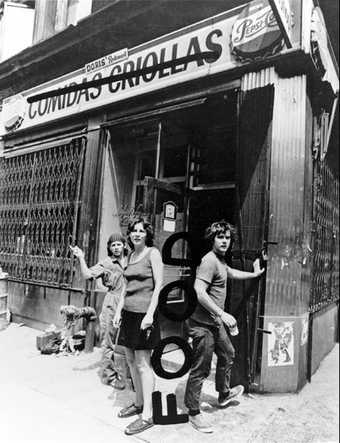

Fig.1

Tina Girouard, Carol Goodden and Gordon Matta-Clark in front of the closed-down bodega that would become their restaurant Food, New York, 1971

Photograph by Richard Landry with alteration by Gordon Matta-Clark

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2017

The photograph of Matta-Clark, Goodden and artist Tina Girouard standing in front of Comidas Criollas, the old bodega that they planned to renovate, demonstrates an engagement not only with the infrastructure of the neighbourhood but with its social structure as well (fig.1). All three look at the photographer. Girouard points to the sign, Goodden holds the keys, and Matta-Clark pushes back the bars meant to protect the building from vandalism. When they had completed the remodel, the bars on the windows had been removed, Food was painted in monochromatic tones, and one of its windows was filled with flyers and notices (fig.2); indeed, it looked not unlike many hip New York eateries do today. It is worth looking closely at that window – an organic message board for neighbourhood goings-on that may have included announcements for exhibitions, calls to action and advertisements for goods and services. The window acts as a site of commerce and exchange at the perimeter of another site of commerce and exchange, namely the restaurant of which it is a part. The paper notices fill the entirety of the window, obscuring the view outside and transforming window into wall. Taken together, the paper notices enact the idea of a wall, as described by landscape architect Thomas Oles, ‘as a place of truck – of interaction and exchange’.2 Walls Paper’s visual characteristics are similar: rectangular paper images that also tell a story of commerce and exchange, although the dilapidated walls pictured in Walls Paper contrast with the newly refurbished windows of Food.

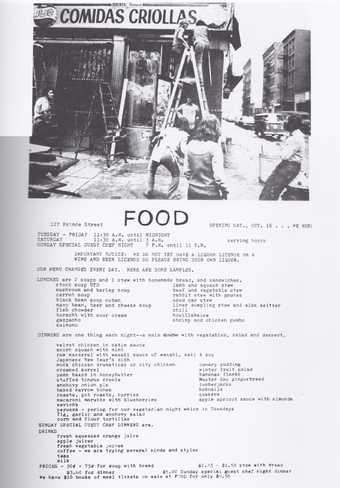

Fig.2

Exterior view of Food after the renovations, 1971–2

Cosmos Andrew Sarchiapone papers, circa 1860–2011, bulk 1940–2011, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Perhaps most importantly in the context of Walls Paper, Food was a sanctioned site for Matta-Clark’s first building cuts. The remodelling of Comidas Criollas necessitated the removal of certain walls. As Goodden remembers it: ‘While we were putting Food together, there was a piece of wall that had to come out. Gordon decided to cut himself a wall sandwich: he cut a horizontal section through the wall and door and fell in love with it. And so the cutting pieces began.’3 Goodden’s reference to a ‘wall sandwich’ mixes the ideas of sustenance and structure, a succinct merging of Matta-Clark’s belief in the alchemical nature of architecture. Food also generated photographs, posters and advertisements. The photograph discussed above, for example, exists in two versions – one unaltered (and ostensibly a document), the other, illustrated in fig.1, with the word ‘FOOD’ vertically wedged between Goodden and Matta-Clark, and with a black line crossing through the older signage. A notice announcing Food’s projected opening of Saturday 16 October (‘we hope!’) demonstrates the ambition of the menu while underscoring the provisional nature of the enterprise (fig.3).4 The photograph above the poster’s text shows two people atop a ladder, fussing with the restaurant’s previous signage, watched by five onlookers. Two more ladders are visible, and the only indication that something culinary is taking place is one viewer’s apron-adorned backside.

Fig.3

Poster and menu for Food, 1971, featuring a photograph of the renovations by Richard Landry

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2017

Matta-Clark’s later practice has been characterised as a deconstructive enterprise, since so many of his building cuts were facilitated by the impending demolition of the structures on which he performed his brand of subtractive sculpture. Yet alongside this Matta-Clark worked, more traditionally, in construction. He was constantly engaged in renovation. As Matta-Clark’s friend Manfred Hecht recalled: ‘We were working on construction jobs downtown. Half of Gordon’s life was constructing lofts. He was always building a place – 98 Greene Street, his Fourth Street loft, Food, his place on Wooster Street. It seems at that time everybody was always building something.’5 Food was perhaps Matta-Clark’s most memorable instance of his work in this capacity. The fact that Food produced the first building cut demonstrates that for Matta-Clark, the building cuts are not deconstructive, but rather productive acts that generated new, previously impossible, experiences with space.

A social hub

Food was a much-needed convening point for a neighbourhood that was undergoing significant social change. Due to the fact that Soho was not yet considered a residential neighbourhood, it had little to offer in the way of eating establishments – especially after business hours. Artist and musician Laurie Anderson described the need for Food as growing from the creative activity burgeoning in downtown New York:

New York in the early 70s was Paris in the 20s … We often worked on each others’ pieces and boundaries between art forms were loose. Soho was pitch black at night, there were two restaurants (‘Food’ and ‘Fanellis’) one gallery (‘Paula Cooper Gallery’) … We were very aware that we were creating an entirely new scene (later known as ‘Downtown’). Gordon Matta-Clark was the center of this scene.6

Food soon became a hub of the Soho art community because it offered artists not only a place to gather but also, perhaps just as importantly, an opportunity for flexible employment and nourishment.7 Thus, while Food filled a useful void in the neighbourhood, providing much-needed sustenance, it also became, as art historian Nicole Woods puts it, ‘a serviceable, social-able artwork’, as artistic labour became part of a transactional performance for an audience mostly consisting of other artists.8 Like many of Matta-Clark’s endeavours, Food combined disparate media and willfully crossed formal boundaries. Sincere and sly at the same time, it functioned readily as a restaurant, performance site and relational artwork.

In many ways, Food answered the question of what was to become of New York’s decaying industrial infrastructure. ‘Food’s Family Fiscal Facts’, published in Avalanche in Spring 1972, exemplifies the mix of industry, art and community that went into Food in its early years as a dining establishment. Alongside the accounting amounts (which included the assertion that no income was rendered through dues and subscriptions) are the more humorous yet dubious statistics on the restaurant’s day-to-day operations. For example, zero internal fights seems hard to imagine given that there are three reported ‘unfulfilled promises by good friends’. Meanwhile, the claim that ‘213 people needed to get it together and keep it together’ alongside the ‘3,082 free dinners given’ and the extensive list of names at the bottom of the flyer attest to the labour of an extensive community (albeit one that eventually ate away Goodden’s savings).9 As art historian Pamela M. Lee has noted, the restaurant was the perfect conjunction of food, architecture and sociability; Matta-Clark’s wall fragment from Food then becomes, for Lee, ‘at once constituted by and posits the ensemble out of which it emerges’, a relationship that is never fully autonomous; it is an index, as well as a material thing.10 Similarly, Walls Paper exists in a network with the built environment. It pictures inside walls turned outward, installed inside the reclaimed space of 112 Greene Street and alongside Matta-Clark’s first para-artistic foray into urban redevelopment.