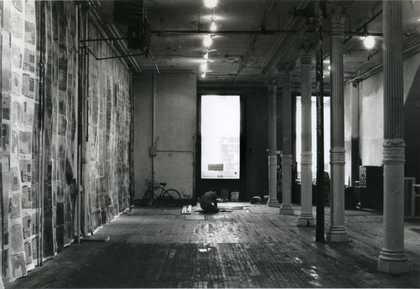

Fig.1

Installation view of Projects: Pier 18 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1971, featuring the work of Gordon Matta-Clark

© Museum of Modern Art, New York

During the summer of 1971, a little over a year prior to the exhibition at 112 Greene Street in New York that included the debut of Walls Paper 1972 (Tate T14658), Gordon Matta-Clark was featured in a show in what might be considered a surprising venue for his work – the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in midtown Manhattan (fig.1). While it may be tempting to think that Matta-Clark was an art world renegade who exhibited mainly on the fringe, he was readily accepted by the avant-garde art establishment, especially as the son of established surrealist painter Roberto Matta and the product of an elite Manhattan education.

Matta-Clark at MoMA

Matta-Clark’s inclusion in the display at MoMA – by this time a world-renowned institution for the exhibition of modern and contemporary art – was facilitated by artist, curator and publisher Willoughby Sharp, who had organised an early exhibition of earth art at Cornell University in 1969. It is no coincidence that Matta-Clark was on Sharp’s radar, since he had served as Sharp’s assistant during the coordination of the Cornell exhibition, which featured a remarkable roster of artists including Robert Smithson, Dennis Oppenheim, Jan Dibbets, Richard Long, Robert Morris and Hans Haacke.

The MoMA exhibition, entitled Pier 18, was part of the museum’s ‘Projects’ series, which was initiated in May 1971 as ‘a series of small exhibitions presented to inform the public about current researches and explorations in the visual arts’.1 MoMA’s press release for Pier 18 announced the show featuring Matta-Clark as the latest in ‘the series of recent experimental work’.2 The ‘Projects’ series likely also answered to criticism of MoMA that the museum had strayed from its original mandate to exhibit contemporary work, as it increasingly became known for its establishment of a canon of modernism. Nonetheless, it is significant that Matta-Clark showed in the series and that his work with the derelict piers along the Hudson River – cathedrals of the industrialised nineteenth century – began not with Days End 1975, in which he cut holes and channels into the floor, ceiling and walls of the Pier 52 building in Chelsea, but four years earlier at Pier 18 and with an institutional mandate (if not the authorities’ permission).

Fig.2

Cosmos Andrew Sarchiapone

Gordon Matta-Clark installing Walls Paper at 112 Greene Street in 1972

White Columns Archive, New York

The images in the MoMA exhibition, all of which were taken by photographers Harry Shunk and János Kender, documented a performance at Pier 18 in which Matta-Clark ‘piled up trees and other rubbish inside the pier and then hung upside down above the material he had collected’ (see, for example, the photograph Pier 18, Gordon Matta-Clark, New York 1971, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris).3 With eighteen photographs in the show, Matta-Clark was well represented and in good company. The exhibition checklist includes an impressive cross-section of twenty-seven contemporary artists working in performance, photography, conceptual and earth art, some of whom Matta-Clark had worked with for the 1969 Earth Art show at Cornell – Oppenheim, Morris and Dibbets, as well as Daniel Buren, Vito Acconci, Richard Serra, Lawrence Weiner, John Baldessari, Douglas Huebler, Mel Bochner and William Wegman. Perhaps more than anything else, the installation of the project is interesting in light of the format that Walls Paper, with its images of derelict buildings printed on newspaper and covering the gallery wall, would take the following year (fig.2). As with Walls Paper, the performances and interventions were represented in Pier 18 by photographs displayed in contiguous strips – albeit horizontal rather than vertical as in Walls Paper – that were mounted directly on the wall, without frames.

The origins of the ‘non-u-ment’

While Matta-Clark had not yet conceived of the idea of the anti-monument or ‘non-u-ment’ when he undertook Walls Paper, it may have helped crystallise his thinking on this key concept in his practice regarding the poetics of the ruin. Certainly, his work at Pier 18, if not as direct as his transformation of Pier 52 in 1975 for Day’s End, was an encounter with a forgotten relic. In April 1972, six months prior to his exhibition of Walls Paper, Matta-Clark wrote a letter to Dan Forresta of the American Center in Paris in which he ruminated about ruins – an aesthetic that Walls Paper’s images of walls certainly evoke. Matta-Clark wrote: ‘I mean everybody loves a ruin sometime … I realize what a perfect vacuum is needed to preserve our sense of time. That is a manicured vacuum, a cultural devotion to maintaining the identity of constantly disintegrating parts.’4 If a traditional monument is meant to stand outside of time, and to stand for all time, a non-u-ment could point to the impossibility of such an aim, in much the same way as ruins do, participating in the flow of time. Not only does the materiality of newspaper call to mind the ease of disintegration and decay, but the subject matter of the photographs that compose Walls Paper is an obvious reminder of the passage of time and the impermanence of architecture. Calling the ancient ruins of Europe benign because they have been ‘swept clean’ – preserved too conscientiously, perhaps – Matta-Clark goes on to propose non-u-ments to be the most provocative relics. The following year, in a letter to artist and dancer Carol Goodden, he expanded on his idea of the non-u-ment: ‘1) it is just as good at any size 2) it is totally unfit for people 3) it invites the visitor to move away’.5

Fig.3

Gordon Matta-Clark

Walls Paper 1972

72 offset lithographs on newsprint paper

Overall display dimensions variable, each: 860 x 576 mm

Tate T14658

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2017

Could Walls Paper (fig.3) be one of Matta-Clark’s first non-u-mental experiments? Like the building cuts, it is derived first from extrapolation – any photograph operates as an act of extraction. Furthermore, it was the quality of their ruination that made the disintegrating walls of houses in the Bronx and Lower East Side into potential subject matter in the first place. Photography was also an appropriate medium to test the theory that the non-u-ment was ‘good at any size’ – a playful disarming of the traditional idea of a monument, which is almost always meant to be grand and imposing. As a series of photographs, Matta-Clark’s Walls Paper announces that the reproduction of a thing involves the viewer in a new relationship with it, and in printing images on newspaper the artist foregrounded the flimsiness and ultimate frailty of both the walls and their reproductions. Their installation against the walls of 112 Greene Street – a building that was also ruined, but given new purpose as an exhibition space – doubly underscores how places ‘unfit for people’ can be re-imagined under the right circumstances. Moreover, the discordant colours that Matta-Clark used in printing Walls Paper might easily ‘invite the visitor to move away’ but also, as art historian Thomas Crow has noted, evoke a dream space – or, put another way, a space of memory rather than history.6

Documenting the liminal

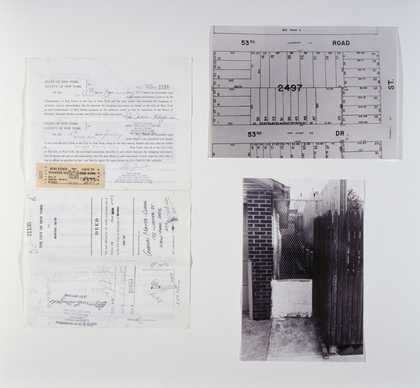

Fig.4

Gordon Matta-Clark

Fake Estates (Little Alley Block 2497, Lot 42) 1973

Photographic collage, property deed, site map and photograph

524 x 567 x 35 mm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2017

Another early photography-based work by Matta-Clark is the relatively better-known Fake Estates 1973 (see, for example, Fake Estates (Little Alley Block 2497, Lot 42); fig.4), which could be seen to function as something of a pendant to Walls Paper. While Walls Paper took vertical space as its subject, Fake Estates is very much horizontal in its orientation, a description of the unbuilt, liminal spaces between parcels of developed real estate. With Fake Estates Matta-Clark’s ideas about property are amusingly articulated. The work’s title is a gesture to the myth of real estate as a clear-cut – even concrete – asset. For the piece Matta-Clark bought gutterstrips of land at an auction hosted by the City of New York, acquiring five parcels at about $25 each, and then methodically catalogued the characteristics of his acquisitions down to the classifications of weeds that were sprouting within their perimeters. Like the source photographs for Walls Paper (see Tate P14439–P14440), but unlike its ultimate form, the photographs in Fake Estates are banal, deadpan and very much in dialogue with other artistic catalogues of urban development, such as Ed Ruscha’s photobook Every Building on the Sunset Strip 1966 (Museum of Modern Art, New York). Yet Fake Estates as a whole – including, that is, the deeds and diagrams that accompany the photographs – becomes a more pointed social critique on the arbitrary concept of property and value. Like Walls Paper, Fake Estates also plays with Robert Smithson’s notion of the site/non-site duality, in which a site was seen to represent a place in the world, while the art gallery – in its deceptively neutral stance – represented a non-site. According to the auction catalogue issued by the City, one of the plots of land purchased by Matta-Clark was supposedly not even accessible, a feature that Matta-Clark told the New York Times was especially intriguing to him.7

In Matta-Clark’s words, Fake Estates was intended to comment on ‘spaces that wouldn’t be seen and certainly not occupied. Buying them was my own take on the strangeness of property demarcation lines. Property is so all-pervasive. Everyone’s notion of ownership is completely determined by the use factor.’8 Matta-Clark’s attention to these spaces – a stretch along a gutter, or the matted grass that complements a concrete driveway – reimagines the private-public relationship with space, questioning the way that society values space based on use-value and ownership, and even challenging the concept of private property.9

Like property lines, walls also enact the division between private and public. In his study of walls, landscape architect Thomas Oles describes them as a tension between two visions – ‘on the one hand, the parcel with its rights of property; on the other, the common, with its obligations of use’.10 Thus we can see walls as physical markers where the rights of the group and the rights of the individual are negotiated. As Oles writes: ‘More than any single object, the wall itself – that thing of wire, wood, stone, or plants – is where this resolution [between self and society] must take place’.11

Fake Estates was executed around the same time that Matta-Clark began his work with the Anarchitecture Group, which he helped to found and, perhaps unsurprisingly, to name.12 Fake Estates maps easily onto the stated interests of the Anarchitecture Group, which Matta-Clark described in 1974 as follows:

We were thinking more about metaphoric voids, gaps, leftover spaces, places that were not developed … for example, the places where you stop to tie your shoelaces, places that are just interruptions in your daily movements. These places are also perceptually significant because they make reference to movement space.13

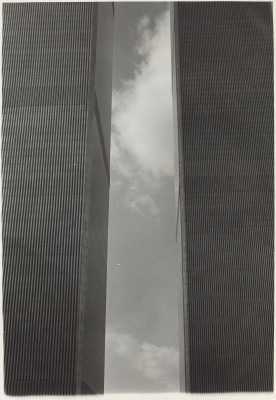

Fig.5

Anarchitecture Group/Gordon Matta-Clark

Anarchitecture: World Trade Towers 1974

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2017

The Anarchitecture Group recognised the potential for unruliness in those leftover spaces between more conventional architectural structures. But Walls Paper also explores gaps and interruptions: the loosening of the seams of the urban fabric are not only depicted amid the screenprints of crumbling buildings, but are seen between the strips of newspaper affixed to the coarse walls of 112 Greene Street. As Matta-Clark explained, ‘I am directing my attention … to the gap … between the self and the American Capitalist system’.14

Perhaps this interest led Matta-Clark, acting as a representative of the Anarchitecture Group, to write to Robert Leydenfrost, a graphic consultant for the Art and Design Program of the newly erected towers of the World Trade Center. As Matta-Clark explained in his 1975 letter, ‘because of our special feliggs [sic] for space as artists, we believe we could contribute some positive and interesting insight into the new scale and complexity of the World Trade Center’.15

Combined in the visual field of lower Manhattan, the World Trade Center and the wharfs that Matta-Clark worked with (Pier 18 in 1971, and later, in 1975, Pier 52) were thrust into an uneasy dialogue with each other. Both sets of structures were built as commercial enterprises, as pantheons to current technology, and were constructed on a grand scale; yet the wharfs had drifted into ruin, while the World Trade Center towers, in Matta-Clark’s time, were intended to be ‘the world’s tallest buildings’, an instant monument to the triumph of capitalism.16

In the photograph of the towers seen in fig.5, which is credited to the Anarchitecture Group but likely taken by Matta-Clark himself, the focus is on the space

between the towers, the literal gap between architecture and

its grandiose rhetoric.

In a later interview with critic Donald Wall, Matta-Clark elaborated on the idea of the non-u-ment: ‘One of my concerns here is with the Non.u.mental, that is, an expression of the commonplace that might counter the grandeur and pomp of architectural structures and their self-glorifying clients’.17 If the monument is about fixing a place in history by giving shape to memory and form to power, the non-u-ment is about a forsaking of power, a stepping outside of boundaries, and a release from the economic constraints of space. Matta-Clark mined his once-stately urban surroundings to expose how easy the transition was between architecture and ruin. The photographs of that investigation memorialise these structures to a certain extent, but they purposely do not transcend time and place.

Soho unclaimed and reclaimed

As a neighbourhood Soho was also subject to the same slippage, and it had also now been reclaimed. Its outmodedness was the precise quality that enlivened it again, making a building like 112 Greene Street a candidate for non-u-mentality.18 Already by 1970 Soho was being touted as the ‘last frontier of bohemia’.19 Time magazine estimated the number of artists living in the lofts of Soho at between 2,000 and 3,000, noting that the ‘continuing presence of workmen and small manufacturers makes for a rewarding combination of art and industry’.20 As an article in Esquire on the transformation of Soho succinctly put it, ‘One lives in work’.21

Like so many of Matta-Clark’s later interventions into the built environment, his early projects were enabled by – indeed, were only possible as a result of – Soho’s obsolescence as a manufacturing neighbourhood. Until 1971 Soho was specifically slated for demolition and eventual redevelopment.22 Obsolescence, outmodedness, and the spaces that seemed useless because of changing socio-historical conditions – these factors formed the foundation of Matta-Clark’s life’s work.

In a section of her 1971 article ‘Surprise Catch from Pier 18’ that bears the subheader ‘So, Ho!’, thus underscoring the pioneering spirit of those living in the area, art critic Grace Glueck reported that artists had recently won the right to the legal residency of loft buildings in Soho, which had previously been zoned exclusively for manufacturing: ‘“The city finally said, ‘okay, live there’”, says Doris Freedman, chairman for Citizens for Artist Housing.’23 In order to live legally in Soho, artists had to register with the Department of Cultural Affairs.24 This strange process – the official sanctioning of an avant-garde lifestyle – was a contradiction that Matta-Clark may have appreciated in the development of his ideas on the non-u-ment. Jane Crawford, Matta-Clark’s wife, recalled how her ‘building had no heat during the weekend, so we froze in the winter’, stating further that:

We often had to put in our own plumbing and electrical wiring, which likely could not meet the legal requirements of the residency codes, but it did provide artists with work – like Gordon, who did the construction … There was kind of an underground telephone warning system if a building inspector was seen in the neighbourhood, giving us time to camouflage our living space.25

Such descriptions reveal Soho’s history as a once-thriving manufacturing space and its vibrancy as a centre of creative (but decidedly non-commercial) activity, conditions that made it a perfect non-u-mental setting.

As Matta-Clark activated the walls of 112 Greene Street with Walls Paper, transformed lofts into liveable spaces and restaurants into performative gatherings, he was actively repurposing the grand ruins of a previous economic structure as a site for the ritual of artistic practice. It is ironic, therefore, that through the refurbishing of previously forgotten spaces, the lofts of Soho became economically valuable again, and the real estate developers eventually came to claim them. Urban sociologist Sharon Zukin described this shift in 1982: ‘Lofts changed from sites where production took place to items of cultural consumption’.26 112 Greene Street eventually became an official ‘alternative space’ and the cultural activity taking place in Soho returned the neighbourhood to the economic forces of real estate, thereby destroying its non-u-mentality.

Fig.6

The Turbine Hall, Tate Modern, London, c.2000

Photo © Tate

Art historian and critic RoseLee Goldberg has stated that for a while, however, ‘there was a sense of ownership of downtown that the creative community had this very special, almost secret place that was separate from the rest of New York. It was cheap rent that made the expansiveness of this community possible, and it would almost entirely shape the aesthetics of the next thirty years. It was the first time that galleries looked like an artist’s loft and vice versa.’27 Loft spaces facilitated the mixing of disciplines, able to accommodate broader ideas of exhibition and performance. It cannot be taken as mere coincidence that the artist’s live/work loft environment eventually trickled into the museum world. A space like Tate Modern in London (fig.6) – a power station built in the 1940s and converted at the end of the twentieth century to house modern and contemporary art – is entirely appropriate for the display of work by 1970s artists who occupied ex-industrial spaces that fulfilled the twin requirements of affordability and flexibility.

Living and working in Soho during the 1970s was initially a way to participate in the art world without the necessity of selling what was then unsellable work. In an issue of Time from 1970, alongside an article singing the praises of the bohemian environment fostered by Soho’s nineteenth-century industrial spaces, is a piece on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition of nineteenth-century American period rooms – parlours featuring ornate furniture that exhibited a ‘shameless relish for the lives of the very rich’.28 There could not be a more succinct way to describe the diverse legacy of the nineteenth century. While its industrial infrastructure was being reclaimed to form open-ended spaces for an avant-garde that eschewed the object, its drawing rooms were meticulously remade in the halls of one of the most prestigious museums in the United States.

Matta-Clark was aware of these kinds of institutional intrusion: ‘even though my work has always stressed an involvement with spaces outside the studio-gallery context, I have put objects and documentation on display in gallery spaces. All too often there is a price to pay due to exhibition conditions; my kind of work pays more than most just because the installation materials end up making a confusing reference to what was not there.’29 As Matta-Clark recognised, the exhibition format and its designated space for display rewrites work on its own terms. Like the situationists whom he admired, Matta-Clark’s work – coming at the intersection between architecture, installation, sculpture, performance, film, photography and cuisine – does not lend itself well to museum display.30 The result sometimes re-inscribes the very spectacle that the artist intended to undermine.

Tate Modern’s massive Turbine Hall recalls the industrial scale that the artists of Soho occupied. When the building opened in 2000, it exemplified the ways in which industrial structures could be repurposed for art on an institutional – and colossal – scale. A 2001 article by John Loughery on museums at the turn of the twenty-first century worried over the possibility that architecture could overpower art in these contexts: ‘What it all comes down to is this: art is fragile, architecture is not’.31 Yet Matta-Clark’s work disrupts these kinds of binaries, subverting the tropes of architecture. Walls Paper in particular exposes the shifting terrain of cities, delicately articulating the tension between architecture and ruin, and intervening in the space between the shiny spectacle of capital and its eventual, inevitable decay.