In the following conversation, conducted in February 2017, Sandra Zalman and architectural historian Philip Ursprung reflect on Matta-Clark’s practice in the context of 1970s New York and its ongoing legacy. They discuss the significance of Matta-Clark’s works on paper, including Walls Paper (Tate T14658; fig.1) and the artist’s photo-collages; his attitude towards his architectural education; and how his work addresses the processes of rapid urban structural and social change in ways that still resonate with the transformations seen in cities today.

Fig.1

Gordon Matta-Clark

Walls Paper 1972

72 offset lithographs on newsprint paper

Overall display dimensions variable, each: 860 x 576 mm

Tate T14658

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2017

Sandra Zalman: Regarding Gordon Matta-Clark’s photography and works on paper, such as Walls Paper, I think it is safe to say that these have not received as much critical attention as Matta-Clark’s ‘building cuts’. How would you position Matta-Clark’s works on paper with regard to the rest of his oeuvre?

Philip Ursprung: Walls Paper is known to specialists because it was published as an artist’s book in 1973 (Tate T14659) and has been written about in the literature on the artist. In general, however, Matta-Clark’s works on paper – paper cuts such as Untitled (cut drawing) 1977 (Walker Art Center, Minneapolis), but also drawings – are less known than the photographs and photo-collages of the building cuts. On the one hand, the building cuts are so spectacular and unique that all other media that Matta-Clark used – for instance films and videos, artist’s books and his writings – stand in their shadow. On the other hand, the works on paper do not reproduce well; they are not as photogenic as the building cuts. If one has never seen the paper cuts or Walls Paper in reality, it is difficult to imagine their spatial presence and the haptic quality of the paper. Nevertheless, the work on paper plays an important role. It stands at the intersection between text and materiality, and this is where much of Matta-Clark’s artistic production starts. Like the scale model, which for most architects is an indispensible device of design, a flexible medium in its own right, the works on paper, especially his drawings, run like a backbone through his career.

Sandra Zalman: Architectural photography plays such a key role in the way we think about buildings – especially those that we have not experienced first hand. Can you discuss the ways in which Matta-Clark’s photographic practice thwarts the tropes of architectural photography?

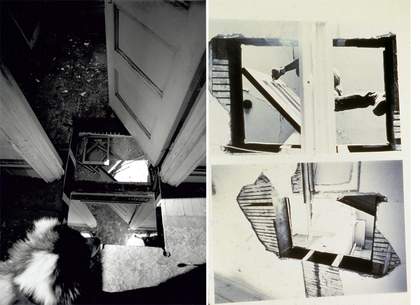

Fig.2

Gordon Matta-Clark

Bronx Floors: Threshole 1972

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

© Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark/DACS 2017

Philip Ursprung: Architectural photography is a very effective medium, because it shapes the way we perceive, compare, value and historicise architecture. But while many architects, when they visit canonical buildings such as Le Corbusier’s 1928–32 Villa Savoye in Poissy, Paris, search for the viewpoint that the camera of the famous black and white photographs took, they rarely conceive architectural photography as a medium in its own right. The reason that so few artists systematically depict architecture is that they fear to lose their autonomy; the reason that so few architects delegate the issue of representation to artists is that they, too, fear to lose their autonomy. Matta-Clark has fully exploited the medium of photography of architecture by working with unexpected angles of the camera (see Bronx Floors: Threshole 1972; fig.2), collaging prints in order to get new forms of spatial representation, experimenting with printing techniques to a degree where he would fry photographs in a cooking pan (see Photo Fry 1969, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago), and by selecting motifs that relate to architecture allegorically, for instance collapsed buildings, from newspaper archives. His methods are a challenge to the discipline of architectural photography, because they show a large spectrum of possibilities in architectural representation.

Sandra Zalman: Regarding contemporary architectural practice, Matta-Clark was deeply interested in undoing the idea that buildings were fixed entities. He wanted to show that they were interactive and adaptable for reuse and, as you have written, he ‘showed architects the limitations of their possibilities, and hence their potential … by marking limits, edges, boundaries’.1 How do you see Matta-Clark’s influence on architectural practice today? Are there specific projects that you think gesture to his legacy? How does contemporary architectural practice depart from Matta-Clark’s concerns?

Philip Ursprung: The oeuvre of Matta-Clark appeals particularly to architecture students. Although he never taught, he has established a kind of a school because – at least from my perspective – his work acts as a substitute for an absent architectural theory. Since the 1980s there has been a theory vacuum in the realm of architecture. Theory in the sense of a set of critical norms or as a conceptual horizon has been partially ousted by narratives, the most popular being the narrative of urbanisation. Statistics about the global population, including ‘10% lived in cities in 1900, 50% is living in cities in 2007, 75% will be living in cities in 2050’, are featured on the cover of Ricky Burdett and Deyan Sudjic’s book The Endless City (2007), and this mantra is repeated over and over again.2 The narrative of urbanisation has replaced the narrative of progress that dominated twentieth-century discourse. Matta-Clark offers an alternative to this narrative of planners and investors that is still dominating today’s discourse. His work deals with decay and collapse, with excess and improvisation. His attitude is not pragmatic and opportunistic like that of most architects; he is not eager to fulfil what a client wants. His attitude is rather autonomous, playful and experimental. He constantly invented his own briefs and thus reminds architects about their responsibilities and potential.

Sandra Zalman: You have written about the history of architectural education in the 1950s and 1960s, when Matta-Clark was trained at Cornell University. How would such an education affect his framing of architecture as a social device?

Philip Ursprung: In the correspondence between the artist and his mother, Anne Clark, there is little information about Matta-Clark’s studies at Cornell between 1963 and 1968. We know that he spent a year in Paris and that he considered studying literature or film. We also know that at Cornell there was much emphasis on artistic interventions and that he produced large-scale sculptures as a student. He was an assistant to Dennis Oppenheim and Robert Smithson, among others, on the exhibition Earth Art in 1969 at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell. After graduating he briefly worked in an office for urban planning. But we don’t know about his training in social science and theory. Colin Rowe was the most prominent teacher at the school between 1962 and 1990, but Matta-Clark does not mention his teaching. Later in his career, however, he criticised the formalist training at Cornell. The most striking example of such criticism is an undocumented performance that took place in December 1976 as part of the group exhibition Idea as Model at Peter Eisenman’s Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in New York. The performance was posthumously named Window Blow-Out. Matta-Clark, so it seems, shot holes in the windows of the exhibition space and then mounted photographs depicting building façades with broken windows. It was the only time during his career that he was part of an architecture exhibition. Several historians have interpreted the performance as a critique of the formalism of his teachers, but besides some contradictory oral history sources I have found no evidence that he explicitly aimed such criticism at his educators. I rather read the performance as a critique of the self-referentiality of the show and the failure of 1970s architecture to address the urban crisis.3 I assume that the focus on architecture as a social device is not the result of his training, but quite the opposite – a reaction to what he had not been trained in. In any case, the topic was in the air in New York around 1970; in other words, at the time when he came back and decided to be an artist. Environmental issues, the crisis of infrastructure, the Vietnam War, social housing and gentrification were being addressed by numerous artists and architects.

Sandra Zalman: Since you are an architectural historian, I am curious to get your thoughts on the current interest in revitalising industrial spaces. I see this happening on both the local and international levels – to varying degrees of success. I can’t help but make an analogy between the rehabbing going on today and the ways in which Matta-Clark and his community adapted the industrial spaces of Soho. How would you position this trend within architectural history?

Philip Ursprung: One of the key topics in the last third of the twentieth century is deindustrialisation. Numerous artists, filmmakers and writers address the transformation of the industrial terrain vague into a post-industrial spatiality. Think of the photographs of old factories taken by Bernd and Hilla Becher from the late 1950s onwards, Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker (1979), J.G. Ballard’s 1974 novel Concrete Island, the competition entries for the redevelopment of Paris’s Parc de la Villette in 1982–3 and Richard Rogers’s Millennium Dome in London (2000). Matta-Clark and his cohort of fellow artists stood right at the centre of this dynamic, in a metropolis stricken by urban blight. However, rather than depicting or analysing the process of decay, Matta-Clark performed ways of improving the situation by dealing with what is there, by recycling waste, by focusing on the commons and involving the neighbourhood. In the performance Fresh Air Cart 1972, he offered fresh air to the tired brokers of Wall Street. The collaborative project Food (begun 1971), where artists gathered to cook and eat, prefigured the open kitchen concept and the fusion kitchen of the 1980s and 1990s. Matta-Clark and his comrades – artists, architects, dancers and curators – designed not only spaces, but also an urban lifestyle that has become mainstream.

Sandra Zalman: Related to this is the fact that Matta-Clark, living in Soho in the early 1970s, was particularly sensitive to the forces of urban development. What do you think of the role of artists, museums or other cultural institutions in neighbourhood gentrification?

Philip Ursprung: The process of gentrification has been studied by Sharon Zukin in her groundbreaking book Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change (1982). The process is comparable in many industrial cities between the 1960s and today and is to a large extent a function of real estate prices, which have the following effects: 1) the departure of light industry from a city’s centre due to deindustrialisation; 2) middle class artists, hand in hand with some artist-run initiatives, take over the industrial spaces and oust the working class; 3) upper-middle class professionals oust the artists and mimic their lifestyle; and 4) boutiques, vintage design shops, tourists, delis, galleries and museums arrive, followed by upper class and private condominiums that function as investment.

Matta-Clark and the members of the group Anarchitecture exemplified this process.4 Unlike artists of the earlier generation who worked in the suburbs or the countryside and came to the city on weekends, their generation could afford to live in the centre. Here, work and leisure blurred. The loft, the empty factory space, is the space where production, reproduction and distribution blend. Performances such as Open House 1972, which consisted of a temporary apartment built into an open container on the street, prefigured what theoreticians such as Antonio Negri and Paolo Virno have defined as ‘immaterial labour’.5 What the performances in the container produced, and what at the same time a growing part of society was producing, were no longer objects, but immaterial goods such as relations, affects, language and emotions. But what in retrospect looks like a creative paradise was already under pressure. In the skies of Soho, as we see in several photographs by Matta-Clark, the twin towers of the World Trade Center were nearing completion.

Sandra Zalman: What is the ideal way that museums today can be designed for the display of conceptual, durational or site-specific work, especially those works that may have been conceived in opposition to the museum as a concretised or artificial site?

Philip Ursprung: The ideal bourgeois museum in the nineteenth century had incorporated the earlier period of the ancien régime in the guise of the aristocratic space of the castle. The exhibition space of the late nineteenth century never lacked some comfortable fauteuils and some plants, the attributes of an aristocratic intérieur. Impressionist paintings looked best in gilded frames in the style of rococo. The ruins of an earlier period were the perfect background for the presentation of the new art because they enhanced their triumph over their predecessors. In the second half of the twentieth century, the ideal museum incorporated the period of industrialisation. The empty loft, the ruined factory that the machines and the workers had left, was the best space to exhibit post-industrial art. Art dealer Leo Castelli set the trend in the late 1950s by using a loft as an exhibition space. In 1979 the artist Donald Judd acquired the entire (ghost) town of Marfa, Texas, as the spectacular backdrop for his minimalist sculptures and the works of art in his collection. The Turbine Hall at Tate Modern in London goes furthest in this trend. The empty space represents value as such. While in earlier economic phases the full warehouse was the symbol of wealth, in our present regime of just-in-time manufacturing, wherein materials are delivered to the production line only when they are needed, the full warehouse equals loss, while the empty space symbolises affluence.