The images occasioned by the ‘Battle in Seattle’ in late 1999 could not have been more spectacular: lootings, fire, tear gas, women and men stripped naked in demonstration against brand name bullies such as Gap, Nike, Starbucks, McDonalds and Microsoft, police in riot gear, police in confrontation with protesters, protesters in turtle suits, giant puppets, anarchists who called themselves the black bloc, rubber bullets, pepper spray, bricks, broken windows and city buses frozen in place by nonviolent protesters holding hands (fig.1). In an attempt to restore order at these protests against the World Trade Organization (WTO), the mayor declared a no-go zone and imposed a curfew. The city shut down, but chaos reigned free.1 For one day within this chaos, Allan Sekula wandered the streets with his camera, avoiding sensationalised shots of either violence or triumph, attending instead – as Stephanie Schwartz describes in the opening essay to this In Focus – to ‘the networked alliances of people in the streets’. And rather than present this alliance as composed of hippies or hooligans, or some unfortunate mixture of both, Sekula’s Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000 (Tate L03355) photographs reveal how, in Seattle at least, no single ‘type’ took centre stage in the grassroots struggle against corporate globalisation. As Schwartz writes, Sekula pictured not the face of protest, but ‘one face after another’.2

Fig.1

Seattle police use gas to push back World Trade Organization protesters in downtown Seattle on 30 November 1999

Published at OregonLive.com

Photo © Eric Draper / Associated Press

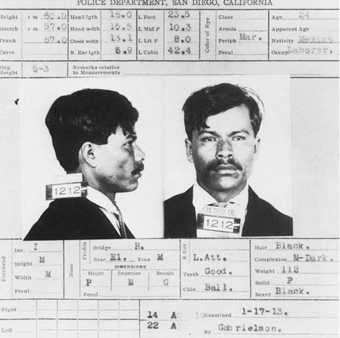

In a statement that accompanied his photo-essay in Alexander Cockburn and Jeffrey St Clair’s book 5 Days That Shook the World: Seattle and Beyond (2000), Sekula explained of his focus on the faces and bodies of protesters: ‘[W]orking at a light table, and reading the increasingly stereotypical descriptions of the new face of protest, I realized all the more that a simple descriptive physiognomy was warranted’.3 For those familiar with Sekula’s work – especially his writing – this language, particularly the phrase ‘descriptive physiognomy’, might at first seem surprising. One of Sekula’s most important essays, ‘The Body and the Archive’, argues that photographs of human subjects – even the most intimate of personal or family portraits – are always haunted by disciplinary archives, systems of surveillance, and a generalising equivalence of the commodity.4 ‘Every proper portrait’, writes Sekula, ‘has its lurking objectifying inverse in the files of the police’, and his illustrations for the essay include examples of the Bertillon card: a document used by police in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that detailed fourteen measurements describing a suspect’s facial and bodily characteristics and featured standardised frontal and profile images of their head and shoulders (fig.2).5 Other scholars, such as Benjamin Young, have also analysed Sekula’s extraordinary commitment to the human figure (not just in Waiting for Tear Gas, but in much of his practice) in light of his critique of the photographic portrait.6 Young explains that Sekula, like Roland Barthes, maintained that photographic humanism (the belief that photography has a special status enabling the communication of ‘universal’ humanistic values) frequently erases specific histories of social struggle and injustice, and naturalises historical meaning.7

Fig.2

Bertillon card, 1913

Reproduced in Allan Sekula, ‘The Body and the Archive’, October, vol.39, Winter 1986, p.35

What to make, therefore, of Sekula’s statement that what he needed to do in Seattle was create a ‘simple descriptive physiognomy’ of the protesters? This essay answers that question by considering how Waiting for Tear Gas operates as a complement to Sekula’s critical writing, and how the pictures put forth their own argument regarding the best way to image the instantiation of the historical, politicised subject. Certainly built in to Sekula’s motivations for the project was a desire to resist portrayals of the anti-globalisation movement as one founded solely in cyberspace – evidenced in part by his use of analogue film, and in part by his emphasis on individual human bodies physically occupying the public space of the street. Yet what makes his photographs of these bodies so remarkable is that they maintain their referential capacity (there is no doubt that these bodies were present on those streets) without making any of the usual accompanying claims about the immanence of truth within the image. Moreover, again with regard to the subject, Sekula effectively translates an indeterminacy or instability of meaning to the formation of a politicised subjectivity. In other words, his pictures reveal a process of political becoming that is relational and ongoing.

For those who attended the Seattle protests, consensus is that it was an event like no other. First-hand accounts tell of protesters hugging in the streets, shedding tears, feeling empowered and ultimately returning to their previous lives only to completely reorient them. ‘It’s great to be alive right now’, declared one protestor, while another claimed that ‘nothing was the same after Seattle’, and another that ‘It was ecstatic; we had won. It was like nothing I had ever experienced before or since’.8 Writer and activist Naomi Klein, whose 1999 book No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies came to function as a declaration of beliefs for the anti-corporate globalisation movement, describes in her article ‘In Case You Missed Seattle, Heeere’s Washington’ (2000) the way in which activists came to recognise Seattle as a turning point. She elaborates, ‘My friend Mez is getting on a bus to Washington, D.C. on Saturday. [After the Seattle demonstrations, Washington, DC was the next slated site for anti-globalisation protest.] I asked him why, and he said with all this intensity: “Look, I missed Seattle. There’s no way I’m missing Washington”’. Klein continues, ‘I’ve seen people speak with that kind of unrestrained longing before, but the object of their affection was usually a muddy music festival … I’ve never heard anyone talk that way about a political protest. Especially not a protest against groaner bureaucracies such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund’.9 Expressed in these first-hand accounts, and in Mez’s regret, is an awareness that something unique happened in Seattle, something previously inconceivable, and they are pertinent here as a means of emphasising that the Seattle protests were a singular event.

Philosopher Alain Badiou describes the ‘event’ as a break with the received ideas of a given context. It defines a threshold bound up with emancipatory politics because, as Badiou writes, ‘emancipatory politics always consists in making seem possible precisely that which, from within the situation, is declared to be impossible’.10 An ‘event’, then, is a self-founding historical moment that breaks radically with the situation from which it erupts and it instantiates a constituent – rather than constituted – form of political power, as well as an emergent political subject exercising that power, which was neither predictable nor even intelligible prior to its eruption.11 Constituent, unlike constituted, political power is not coercive, nor does it codify new social relations. By contrast, constituent political power contains within it transformative potential, as well as an openness to future innovations and new desires.12 The personal stories of those who partook in Seattle express exactly this sort of revelation about their experiences, and the many existing diaristic accounts written and produced by protesters (indeed Waiting for Tear Gas itself might be thought of in these terms) further suggests the impact Seattle had on how participants came to understand themselves as political and historical beings.

However, if in Badiou’s sense of the word a radically transformative event brings the invisible into the world of the seen – if it makes what was unthinkable present and real – what would, what could, a representation of such an event look like? How does one represent what was previously not only unrepresented, but actually unimaginable and illogical? Or more importantly, how can one illustrate an event’s prior unintelligibility? These qualities are essential to Badiou’s conception of the event, and part of what distinguishes it from the purely novel.13 What, too, of the subjects – the people – that make a previously unimaginable action not only imaginable, but possible? What do they look like and how can they be depicted as active, critical social beings in a manner that refuses to banish them to the all-inclusive ‘shadow archive’ described by Sekula in his text ‘The Body and the Archive’?14

Fig.3

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate L03355

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Of Waiting for Tear Gas Sekula writes – as other essays in this project have mentioned – that his guiding principle was, in part, ‘to move with the flow of protest, from dawn to 3 a.m. if need be, taking in the lulls, the waiting and the margins of events’.15 This strategy sounds remarkably modest, but in Waiting for Tear Gas it is key to the construction of potential political subjectivities that recognise the extraordinariness of the event without necessarily embracing something like Badiou’s attendant anti-humanism. As Sekula moves with the flow of the protest, he captures the uncontainable multiplicity of the street, showing subjects constituted in relation to one another, creating space for new narratives to develop, all while producing, on the part of the viewer, an actual feeling of pause. Delay emerges here both on the level of content – we see representations of people waiting, hanging out, wandering around (fig.3) – as well as formally, in the sense that meaning is deferred as the sequence of images gradually unfolds as part of a political process that depends upon the viewer. The viewer in this construction mirrors the protesters’ position: we too are waiting, sensing that something extraordinary might happen (or is supposed to have happened), something that might puncture our established, mundane framework for understanding the world.16

Fig.4

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Fig.5

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

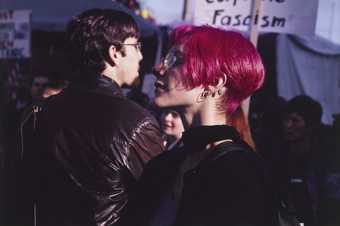

Yet we never grasp or wholly see that thing, that event – instead we are presented only with its preparation and sidelines, quick glimpses and after-effects. In the sequence of images that appears in 5 Days That Shook the World, for example, the second and third images depict a young white woman with pink hair and piercings and a middle-aged white woman wearing a red jacket with a plastic cover (possibly a plastic bag) to protect her from the rain (figs.4 and 5). In both there is a sense of expectation, which mirrors the spectator’s position, as the women concentrate calmly on something beyond the photograph’s frame. The pictures follow each other in sequence, and as the women look in opposite directions, it’s clear that something is happening in multiple spaces beyond the picture, something we cannot see. In a similarly constructed image, the sixth one in the Cockburn–St Clair book, a woman looks out over her left shoulder, toward the viewer’s space (fig.6). The exchange of glances in this image – the woman’s at the unseen protest beyond the picture frame, the policeman’s at the unseen protesters, the photographer’s at the woman and the policeman, and the viewer’s at the picture – generates a multitude of perspectives that both troubles belief in a stable referent and denies us access to the event-scene.17 We are waiting to see something that is supposed to have happened – that we know happened – and yet we never see that thing, and can only hope to do so in the future.

In one sense the photographs that make up Waiting for Tear Gas thus represent nothing so much as omission, an announced blankness that proclaims: yes, these images depict what was once before the camera’s lens – these streets, these protesters, these policemen – but something else is present too, something unknowable. In their simultaneous representation and enactment of the experience of waiting and delay, Sekula’s photographs might be thought of as effectively illustrating what Badiou describes as the event’s prior unintelligibility. They capture, in essence, the future unknown. The temporal ordering of photography, as Roland Barthes explains it in Camera Lucida (1980) as the ‘that-has-been’ past, is reversed. Waiting for Tear Gas does depict a past moment, but one in which a new and unanticipated future emerges; Sekula gives us photographs that necessarily point forward in time.

Fig.6

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

In Camera Lucida, Barthes describes not only photography’s temporal order, but also a feeling of completeness uniquely generated by certain photographs that can cause one to feel as if everything, or everything integral, has been caught in one single image. He identifies this phenomenon as the ‘totality-of-image’, and he contrasts it to cinema’s flux.18 In Waiting for Tear Gas, as we have seen, Sekula structures his images so as to avoid precisely this feeling of wholeness. Rather than the totality of the image, we encounter its incompleteness and indeterminacy, and in denying the viewer any pretence that he or she understands (or even sees) the total situation, Sekula’s photographs acknowledge their own representational limitations. This acknowledgement, in turn, produces two related consequences: it underscores the fact that some things elude representation (and so Sekula’s images become as much about what is not represented as what is), and it creates a contingent model of portraiture that resists any suggestion of portraying a subject fully formed.

Fig.7

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate L03355

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Fig.8

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

If Waiting for Tear Gas points to a future that we do not or cannot yet know, if it shows and creates moments of pause, announces its own limitations, and eludes our stable gaze, it does so precisely because we are brought so close to the event’s participants, we see their faces, we watch them watch, we see their bodies collide in the streets, we are shown their diversity: in age, race, dress and, importantly, in response to the events happening around them. Yet the bodies Sekula portrays are often partially obscured, which further contributes to the construction of a provisional or conditional model of portraiture designed to escape the police file archive. Throughout Waiting for Tear Gas we see lights that obscure rather than illuminate, glares and reflections that distort, figures caught unaware and with their eyes closed, and bodies out of focus (figs.7 and 8). In one image we confront a young man covering his face after being attacked with tear gas (fig.9). Head back and mouth open, his gesture and expression reveal the intense experience of suffering while simultaneously obscuring his face, in part because of his scarf, but also because his backward motion abstracts and makes his features unrecognisable. In another image we see a middle-aged woman half hidden by a scarf, which she raises to her face in order to rub her tearing eyes. In a final example, we see a man dressed in light coloured clothes surrounded by dark figures; he looks down and to the side, wearing a hat, and it is impossible to glimpse his face (fig.10).

Fig.9

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Fig.10

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

All of these effects and framings, in the attention they call to the conditions of their own making, remind us of the always-fragmentary nature of photographic representation. Yet we might also understand this fragmentation as issuing from the uncertainty of the individual’s formation as a political subject. Mere participation in an event such as the ‘Battle in Seattle’ does not guarantee a politicised subjectivity, because such subjectivity is not an effect of the ephemeral present alone; rather, it comes about when individuals convert the temporary appearance and sudden realisation of political actualities forward in time and into a dedicated commitment. The play in Sekula’s images between the visibility and invisibility of the depicted subject and the very real (yet mostly unspoken) possibility of the event’s disappearance speaks to the inherent instability of the ‘event’ – as merely a present actuality – and the euphoric moment of emancipatory politics. It is yet up to participants to realise the event’s long-term significance.

In Seattle, caught off-guard by the strength, organisation and artistry of the protesters, the WTO meeting, like the city itself, was brought to a standstill. The proponents of accelerated free trade were stopped in their tracks: ministers could not get to their opening ceremonies, officials could not attend their private meetings and the conference’s entire first day was cancelled. As the energy from the streets translated to the negotiations, contingents from the developing world, especially African countries, felt emboldened to take stands they might not have taken otherwise, and as they refused to accede to the United States and other rich countries, the ministerial collapsed. In a world of certainties, the protests created a climate in which nothing seemed certain anymore. However, for those familiar with the anti-globalisation movement of the 1990s, it will come as no surprise to hear that the unpredictability of the Seattle protests was relatively short-lived. The kind of bungling police overreaction faced by protesters in Seattle turned, in future protest sites – especially at Genoa in July 2001 – into a quasi-military crushing of dissent.19 After the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City on 11 September 2001, the anti-globalisation movement as it had emerged in Seattle disappeared, at least in an American context. Yet the networks that were formed in the streets of Seattle and the transformed lives go on. Sekula ends ‘The Body and the Archive’ with a call to ‘listen to, and act in solidarity with, the polyphonic testimony of the oppressed and exploited’, testimony, he goes on to say, that might take ‘the ambiguous form of visual documents’.20 By developing a contingent model of portraiture dependent on delay as a way to capture transformed subjectivities, Waiting for Tear Gas functions both as one of these visual documents and as a gesture of solidarity.