Fig.1

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate L03355

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Fig.2

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

On 30 November 1999 the photographer Allan Sekula joined tens of thousands of protesters marching in the streets of Seattle. Moving among ‘the teamsters and the turtles’, to use the colloquial description of the makeup of the motley crew that formed the ranks of the anti-WTO (World Trade Organization) protest, Sekula shot a series of candid photographs. He joined the crowd, getting up close to the sea of red flags and weathered workers, to the bare-breasted women and the devil holding a cardboard chainsaw, to the police and their arms (figs.1 and 2). As he would later explain, he consciously refused the protocols commonly adhered to by contemporary photojournalists: the use of flash, a telephoto lens, a gas mask, auto-focus, a press pass and, most importantly, compliance with media pressure to capture a defining, iconic image of violence (such as Steve Kaiser’s photograph of the police, in full riot gear, pepper-spraying a group of seated protestors; fig.3). Joviality lurks in and among Sekula’s shots. Solidarity trumps scandal. Sekula called his practice ‘anti-photojournalism’.1

Fig.3

Steve Kaiser

WTO Protests in Seattle, November 30, 1999

Posted to Wikipedia entry ‘1999 Seattle WTO Protests’

Fig.4

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Single channel 35 mm slide projection

Installation shot, exterior view, Tate Modern, London, 2013

Artwork © Estate of Allan Sekula

Photo © Tate

Fig.5

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Single channel 35 mm slide projection

Installation shot, interior view, Tate Modern, London, 2013

Artwork © Estate of Allan Sekula

Photo © Tate

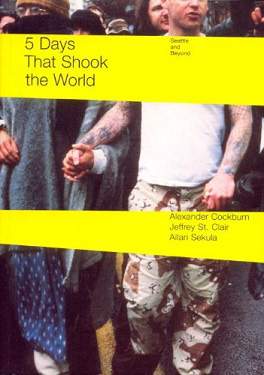

Fig.6

Cover of 5 Days That Shook the World: Seattle and Beyond by Alexander Cockburn and Jeffery St. Clair, London 2000, which features thirty-two photographs by Allan Sekula, ‘Waiting for Tear Gas [white globe to black]’ and accompanying text

Sekula’s commitment to ‘anti-photojournalism’ frames this study of Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000 (Tate L03355), a slide sequence of eighty horizontal and one vertical 35 mm full-frame colour transparencies selected from the photographs Sekula produced moving in and among the crowds on that rainy November day (figs.4 and 5). The slides, which are paced to drop at eleven-second intervals, run on a fourteen-minute loop. They are projected using a standard carousel slide projector, such as a Kodak Extapro 9020,2 and accompanied by a text Sekula penned in Rotterdam in September 2000 explaining his decision to photograph the protest.3 ‘I hoped’, he wrote, ‘to describe the attitudes of the people waiting, unarmed, sometimes deliberately naked in the winter chill, for the gas and the rubber bullets and the concussion grenades.’4 Selections from Sekula’s ‘descriptions’ have also been published as a photo-essay in Alexander Cockburn and Jeffery St Clair’s publication 5 Days That Shook the World: Seattle and Beyond (2000) (fig.6). Thirty-two of Sekula’s photographs close this diaristic account of the protest. Appearing one per page, they are printed full-bleed. As in the slide sequence, one photograph or one protestor bleeds into another. Choreography matters, Sekula’s formatting suggests, but there is no set course in Waiting for Tear Gas. In the book, on the page, Sekula reduced the number of photographs and rearranged their sequence.

This choreographed sequence of shots of the day’s events – marching, chanting, singing, beating and shielding eyes, mouth and nose from the gas and pepper spray – provides neither an obvious nor a single narrative line. There is no crescendo in Sekula’s record. There is no movement from dawn to dusk or from peace to violence. Instead, Sekula challenges viewers to interrupt the scene. Ideally projected at just under 2 x 3 metres, the photographs, Sekula instructed, ‘should have a “life size” quality, as if one could step into the image over a low threshold’.5 Yet, if watching is aligned with acting, the viewer must wait: decide if or when, metaphorically speaking, to step over the divide and join the protest. With Waiting for Tear Gas action is both elicited and not. The viewer watches and waits in the darkened space of the gallery. The dark room heightens the scene and the senses.6 Viewers look at the screen and listen to the automated tick of the slide projector, which both counts and stops time. Waiting for Tear Gas holds the viewer’s attention between still and moving images. With the drop of each new slide, the viewer holds out for the denouement, for the single shot, which never arrives. Viewers, that is, may be simultaneously moved by the camaraderie and the tenacity of the protestors and rebuffed by the artist, who denies them a conclusion.

Fig.7

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

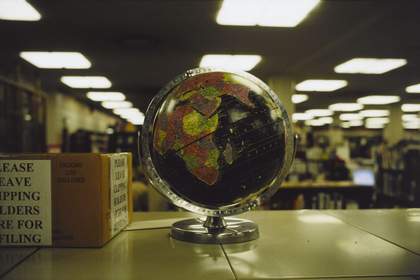

Perhaps not surprisingly, Waiting for Tear Gas does not begin in the street, with the ‘main’ event. As referenced in the subtitle to its accompanying text, [white globe to black], it begins in a library with a close-up shot of a white globe (fig.7) positioned atop a filing cabinet and taking up much of the central part of the frame. Shown in focus, it is the main feature of this otherwise out-of-focus shot. Everything else is blurry: the black globe lurking behind the white one, the stacks of books stretching into the distance, the rows and rows of all-too-white panel lighting. There is no auto-focus, and no depth of field. To begin here, focused on a representation of the whole world, on a technology designed to orient travellers, navigators and citizens in the world, is poignant. This point of orientation is markedly not a beginning. In situ, there is no beginning to Waiting for Tear Gas; there is only a continuous loop. Eighty-one slides is one more than the standard slide carrousel holds. The last slide in Waiting for Tear Gas is also the first. It sits in the carousel ‘gate’ at position number 0.7

The sequence of slides is already moving when the viewer enters the gallery. Waiting for Tear Gas could begin for that viewer with a line of policemen in full riot gear, with the clenched fist of hooded protestor, with a verbal declaration of war or with the simple presentation of rubber bullets – forensic evidence of police brutality (figs.8 and 9). Those who choose to watch and wait will eventually encounter two interior shots: appropriately, in the end, Waiting for Tear Gas loops back to the library. Sekula takes the viewer back inside, but this time he reversed the view (fig.10). The black globe, slide 0, is now in focus, front and centre, and the white globe is cut out of the frame.

Fig.8

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Fig.9

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

A beginning and an end without a beginning or an end, these interior shots frame, as opposed to open and close, Waiting for Tear Gas. The slide sequence oscillates (over and over again) between exterior and interior shots. It oscillates as well between a view from above, looking down at the whole world in the form of the globe shots, and a view from the street, standing among the fragments – another police brigade, another gas mask, another protester, another shot taken in the ‘Emerald City’. Viewers are simultaneously oriented and disoriented. They are moved forward only to be knocked back – to wait. Is the ‘whole world watching’, as the Seattle protestors chanted, recalling the slogan made famous by those protesting the Vietnam War during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago when the TV cameras rolled and beamed footage of police brutality into thousands of homes? Or are the viewers of Waiting for Tear Gas watching representations of the whole world? Waiting for Tear Gas is a record of a protest as a reimaging of and a critical engagement with the media’s reflexive loops.

Fig.10

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

The acts of recall and replay orchestrate the structure or rhythm of Waiting for Tear Gas as well as its subject. The day in question, 30 November 1999 or ‘N30’, was the second of what came to be known, at least in the Western hemisphere, as the most important anti-globalisation protest of the era. Lasting five days, the ‘Battle in Seattle’, the moniker for the protest most favoured by the press, shut down the Third Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization. Sekula did not record this result, nor did he record the ‘battle’ from the beginning until the end. In fact, unlike those photographers carrying press passes or on assignment, he only spent one day in the street. With Waiting for Tear Gas, Sekula eschewed the need for coverage – the possibility or promise of getting ‘the whole story’. He also eschewed the triumph. His camera attended, instead, to the networked alliances of people in the streets fighting for fair, as opposed to free, trade. Teamsters and turtles, teachers and students, preachers and longshoremen moved together and waited for the tear gas.8 ‘[W]orking at a light table, and reading the increasingly stereotypical descriptions of the new face of protest’, Sekula explained in the text accompanying the slide sequence, ‘I realized all the more that a simple descriptive physiognomy was warranted’.9 Waiting for Tear Gas does not provide an end. There is no single iconic shot of either violence or triumph. Likewise, there is no single face of protest: neither the ‘hippie’ nor the ‘hooligan’ take or are given centre stage, but are both equally present (figs.11–12). Instead of the face of protest, Sekula gives us one face after another. As one slide slips into the next, the media stereotype literally dissolves into and re-emerges out of the motley crew and the many. The protest and its representation are inseparable.

Fig.11

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Fig.12

Allan Sekula

Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000

Tate

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Although certainly a major work, Waiting for Tear Gas has often been overlooked in studies of Sekula’s oeuvre.10 This is reflected in the work’s exhibition history. Housed in the collections of several major museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, FRACS, Rhône/Alps, and the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona as well as the Tate collection, Waiting for Tear Gas has circulated most widely as representative of or a precedent for global protest art. It was featured, for example, in ANGRY, Young, and Radical (2011) at the Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam, and in Common Spaces (2014) at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, just two of the many exhibitions examining the radicalisation of public culture in the wake of the Occupy Movement and 9/11.11 Protest, collective action in the streets and the carnivalesque are topical. As Waiting for Tear Gas works so hard to register, they are subject to and the subject of the whims of the press. ‘The new face of protest’ is represented as something that can come into or fall out of fashion. The challenge of looking closely at Waiting for Tear Gas , as this In Focus aims to do, is to look past the moment – the news. It is to consider the need for measured action, for waiting.

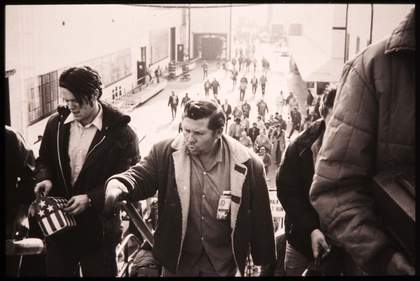

Protest, collective action in the streets and the carnivalesque articulate the subject that had continuously occupied Sekula for four decades: wage labour. He began tackling this topic in the early 1970s with another slide work: Untitled Slide Sequence 1972, printed 2011 (Tate L03352).12 Shot while completing his Master of Fine Arts (MFA) degree at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), this sequence of twenty-five black and white slides records the movements of workers and managers at the end of a day’s shift (fig.13). The young graduate student stood at the exit of San Diego’s Convair Aerospace Factory and photographed its employees head-on, until he was asked to leave the premises for trespassing. Sekula did not record labour as such. Rather, the sequence of slides, or, to be more exact, the subjects represented as a sequence, excavates labour’s social conditions. Labour is represented as a set of routine or routinised actions, such as the passage between the spaces of work and spaces of leisure or between the time spent inside the factory and out in the street, on the way, perhaps, to the pub, the union hall or the living room.13

Fig.13

Allan Sekula

Untitled Slide Sequence 1972, printed 2011

Tate L03352

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Like a number of artists and writers teaching and studying at UCSD in the 1970s, Sekula was charged by the twin pillars of the growing military–industrial complex: the war in Vietnam and the fiscal crisis.14 Upon the completion of his MFA in 1974, he began writing and publishing widely, offering historical accounts of photography’s social uses and acerbic views on its then-recent embrace by the art market. Many of these appeared in the magazine Artforum, eventually to be collected in Sekula’s Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works, 1973–1983 (1984). Combining theory, history and practice, this collection shaped critical thinking about photography for the next few decades as well as about Sekula’s work with the slide sequence and essay form.

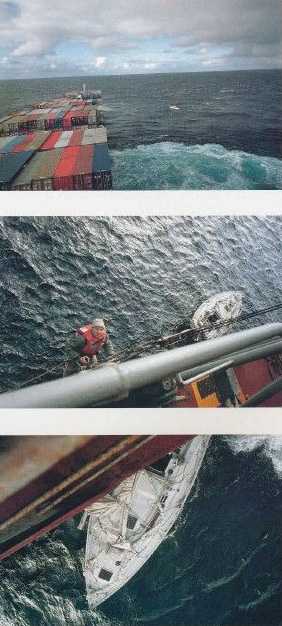

Fig.14

Allan Sekula

Images from a page from Sekula’s photo-essay and book Fish Story (Düsseldorf 1995, p.62), where they are accompanied by the caption: ‘Conclusion of the search for the disabled and drifting sailboat Happy Ending’

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Seminal in this respect is Fish Story 1989–95, Sekula’s photo-essay and book in which wage labour is once again featured (fig.14). This time Sekula turned to the ‘forgotten’ labour of the sea.15 Built out of ninety-six photographs he shot during his travels through the world’s ports, Fish Story queries the assumption that since the 1970s labour had become immaterial. Like the myth about free trade sold by the WTO, the myth about ‘the end of work’ is debunked in Sekula’s frames. Men and women break their backs, still, at sea. The sea, not the ‘information superhighway’ that is the internet, moves vast amounts of goods and people. The argument here is not simply that manual or material labour still exists. It is that few describing the economic logic of late capitalism, of globalisation, want to recognise that it is still more economically advantageous than not for those controlling the means of production to pay people little to labour in traditional ways. In other words, few represent this reality as one of the central conditions for the operation of globalisation and the licence of ‘free trade’. As Sekula asked in the opening pages of Fish Story:

How do governments – and the actors who speak for governments – move cargo? How do they do it without stories being told by those who do the work? Could the desire for the fully automated movement of goods also be a desire for silence, for the tyranny of the single anecdote?16

Puncturing myths is never enough, as Roland Barthes has taught us (and Sekula has reiterated) with the media’s stories in mind.17 It is myth’s structure – the sequence and the story, the silence – that matters and must be excavated. It is this excavation that has been Sekula’s project since the 1970s.

Waiting for Tear Gas should not be categorised as work about protest; nor, for that matter, should it be categorised as ‘a work’. It must be seen as one part or facet of the story Sekula simultaneously narrated and unravelled for over four decades about the representation of social relations and the perverse logic of global capital.18 The sequence’s exhibition history also reflects this process or practice. Key here is Sekula’s insistence on including a selection of photographs from Waiting for Tear Gas in the 2005 publication Constantin Meunier: A Dialogue with Allan Sekula.19 Sekula’s negotiation of the monumental image, the iconic shot, in Waiting for Tear Gas neatly frames his ‘dialogue’ with the nineteenth-century Belgian sculptor’s Monument to Labour 1905 (on public display at the Quai des Yachts, Brussels). Likewise, the dialogue reframes Waiting for Tear Gas. Seattle is now one part of a much longer history of the representation of struggle. The slide sequence, like its ‘story’, is neither topical nor complete.20

Never providing a simple or singular record of ‘the time’, Sekula’s slide-sequences, books and photo-essays allow representations to proliferate. This proliferation is most evident in Waiting for Tear Gas: in this work, viewers get a literal proliferation of workers – those, for example, able to take a day off work to protest, those who once had work and are now unemployed, those off-screen, out of sight, working in the developing world without a wage, and those, behind glass doors, still working. Likewise, with this representation of action that ends as it begins, time itself proliferates. Sitting in the darkened gallery space, viewers confront the dismantling of photography’s conventional morphology: a cut in time. In Waiting for Tear Gas, time extends and loops, is uncut. Rebuffed, pushed forward by the next slide, viewers are both charged to wait and to answer back. The contemplation of the cut becomes impossible.21 This impossibility reminds us to query the subject of Waiting for Tear Gas, which is also the subject of much of Sekula’s work: who writes history? Which histories get told and sold? Which histories are in our ‘playback loop’? These questions frame the four essays that follow in this In Focus project.