Fig.1

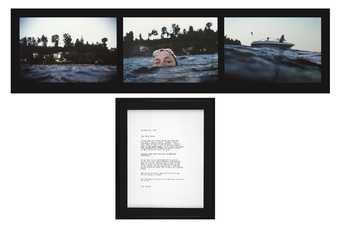

Allan Sekula

Dead Letter Office 1997

Twentieth Century Fox Set for Titanic, Popotla, Baja California

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Allan Sekula coined several neologisms to characterise his work and its method. ‘Anti-photojournalism’, for example, is joined by ‘counter-forensic’, ‘counter-site’, ‘counter-image’ and the rather particular ‘anti-Titanic’.1 The latter term was developed in the context of Sekula’s thoughtful and extended response to Hollywood’s romantic rendition of the perils of seafaring and industrial hubris, James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster film Titanic. Sekula visited the movie set in early 1997 and recorded what he would later refer to as the studio’s ‘lugubrious arrogance’.2 Seeking profits from lower Mexican wages, Twentieth Century Fox built the film set, which featured the largest ever freshwater filming tank, adjacent to a fishing village on the Baja California coast that had no running water. Efflux from the tank lowered the salinity of the village’s coastal tidal pools, devastating the mussel-gathering livelihood of the villagers.3 A diptych of photographs taken on the set, which opens Sekula’s photo-essay Dead Letter Office 1997, is ‘anti-Titanic’ (fig.1). Its promise of a panoramic view, the view in the film associated with the line ‘I’m the King of the World’, is blocked. Instead, a claustrophobic maritime space ensues. The sinking set seems to slip out of sight behind a crane, mounds of dried, cracked earth and a now all-too-brilliant polychrome landscape. As Sekula explained:

We peer morbidly into the vortex of industrialism’s early nose-dive into the abyss. The film absolves us of any obligation to remember the disasters that followed. Quick as a wink, cartoon-like, the angel of history is flattened between a wall of steel and a wall of ice. It’s an easy, premature way to mourn a bloody century.4

On the set and the screen, Hollywood remixed industrial hubris in accordance with the buoyancy of the 1990s’ dot-com bubble.5 Speculation, Sekula charged, submerged – at least for a moment anyway – the lessons and tragedies of modernisation.

Fig.2

Allan Sekula

Dear Bill Gates 1999

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

© Estate of Allan Sekula

The claustrophobic diptych is one part of an exhibition programme and book project Sekula eventually called TITANIC’s Wake 2001/2003, as is the subject of this In Focus, Waiting for Tear Gas 1999–2000 (Tate L03355), Sekula’s account of the 1999 World Trade Organization (WTO) protests in Seattle. The pun on the damage and destruction left in the film’s mechanised wake frames a tripartite meditation on the damage and destruction wrought by neoliberalism and globalisation, of which the WTO was one major development. As well as Waiting for Tear Gas, the TITANIC’s Wake project featured Dear Bill Gates, a triptych of photographs, including one depicting the media mogul’s colossal home, accompanied by a type-written letter from Sekula to Gates querying his purchase of Winslow Homer’s painting of two fishermen, Lost on the Grand Banks 1885 (fig.2). These joined the title project, TITANIC’s Wake, a twenty-three-photograph documentary diary of the antimonies of globalised production, which included overhead shots of the gleaming and undulating surfaces of Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum for Bilbao and a detail of another watery grave, a shipwreck in Istanbul (figs.3 and 4).6 In the book and exhibition, top-down nostalgia for the sea in Gates’s taste for nineteenth-century shipwrecks, Cameron’s spectacularisation of a mass grave and Gehry’s imported maritime mausoleum confront a movement from below querying the promises of the new economy.7 Or, to quote Sekula from one of the many texts he penned for the 2003 publication, the slick liquidity of the markets (as well as the internet and postmodernism’s rhizomatic architectural forms) confront the forced and controlled liquidity of the police state’s chemical production of tears.8 As with the eighty-one slides in Waiting for Tear Gas, in TITANIC’s Wake juxtaposition – the complex choreography between moves from above and counter-moves from below – is paramount. Sekula’s diptychs, triptychs and essays deliver and withhold, repeat and retract, the narratives we tell and are told about the successes and failures in Seattle. There is never just one story.

Fig.3

Allan Sekula

Bilbao, from TITANIC’s Wake 1999/2000

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Fig.4

Allan Sekula

Shipwreck and worker, Istanbul, from TITANIC’s Wake 1999/2000

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Sekula’s neologisms and puns foreground his appetite for unearthing and producing new narratives, as does his appeal to philosopher Walter Benjamin’s ‘angel of history’. It is hardly surprising that Sekula would have been captivated by Benjamin’s characterisation of progress as a storm propelling the angel into the future, which appeared in the ninth thesis of Benjamin’s ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ (1940). ‘The storm’, Benjamin wrote, ‘irresistibly propels him [the angel] into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.’9 Benjamin’s angel is a ‘counter-image’. History blows back. Progress, not regress, leaves one disaster after another in its wake. Further developed in the other seventeen theses of Benjamin’s philosophy as a critique of historicism, of the telling of history as a teleological unfolding of time, this characterisation of time’s movement shaped Sekula’s most famous, although borrowed, turn of phrase: ‘against the grain’. Part of the title of his 1984 publication Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works, 1973–1983, it is lifted from the last lines of Benjamin’s seventh thesis. Some of the most famous lines of the text, they read as follows:

There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is not free of barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another. A historical materialist therefore dissociates himself from it as far as possible. He regards it as his task to brush history against the grain.10

With TITANIC’s Wake, Sekula neither simply nor solely told a different story – from the street, for ‘the people’, on the left, and so on. He brushed history against the grain, telling the story that always gets told differently.

It is with this difference in mind that we can consider the neologism framing Waiting for Tear Gas: anti-photojournalism. Although noted in almost every study of the slide sequence, the ‘counter-phrase’ has been surprisingly understudied.11 Few taking stock of the term, that is, have thought to ask a rather simple question: what is photojournalism? For most, photojournalism is simply synonymous with mainstream media. It is spectacular photography, with all the insidious connotations of the popular understanding of that term. Yet the question that remains, and the question that will be posed here, is as follows: is Waiting for Tear Gas, in fact, a form of photojournalism? After all, it was the photo-essay or a choreographed sequence of photographs that emerged as the means of reportage on the pages of the newly illustrated press in the 1920s and 1930s and which was deemed outmoded the very year Sekula began to work in its form. It was in 1972, the year Sekula completed Untitled Slide Sequence, that the most important and popular American illustrated magazine, Life, stopped printing.12 After thirty-six years selling the news in photo-essay form, Life’s editors saw the television screen finally eclipse the page as a means of both its generation and distribution.

Fig.5

Workers Film and Photo League of the Workers International Relief

Still from Hunger March 1931

Restored by Leo Seltzer 1982

If we account for this history – that is, if we account for histories of media – then new questions necessarily emerge about Sekula’s ‘counter-move’. In Waiting for Tear Gas, was Sekula, to borrow another of his key concepts or terms, ‘reinventing’ photojournalism in the wake of the rise of another new means for circulating and generating news, namely the internet?13 To pose this question is not to suggest that Sekula’s work is nostalgic – that with his essays and slide sequences he sought to return to an old or outmoded form. He was, after all, highly suspicious of the popular press and what he characterised in 1978 as its ‘corporate’ form. Writing of the ‘reinvention’ of documentary in his seminal essay about the ways in which our canonical histories of modernism have purposely repressed histories of documentary, Sekula spoke with disgust about the photo-essay, referring to it as a ‘cliché-ridden form that is the noncommercial counterpart to the photographic advertisement’. ‘Photo essays’, he continued, ‘are an outcome of a mass-circulation picture-magazine aesthetic, the aesthetic of the merchandisable column-inch and rapid, excited reading, reading made subservient to visual titillation’.14 This is quite damning prose. With Waiting for Tear Gas Sekula did not return to this form. He ‘reinvented’ it, offering a ‘meta-critical’ analysis of photojournalism.15 Recording the protest in Seattle through an investigation of the protest’s mediation, Sekula took stock of the ways in which photojournalism had been co-opted and historicised. After all, as Sekula acknowledges on the pages of the same essay in which he condemns the mass-circulation picture magazine, the photo-essay was also a radical platform for disseminating information and the news. Sekula offers readers the productions of the Workers Film and Photo League as one important example.16 Before they were appropriated to form ‘the merchandisable column-inch’ or as the complement to advertising, choreographed sequences of images signified a break with photography as a contemplative cut in time. On the page and in film – in motion, that is – a multiplicity of views ensued (fig.5). Never static or given, subjects were social, even socialised, through the page and the sequence, in time. In turn, it is worthwhile asking: is ‘anti-photojournalism’ a critique of photojournalism, or is it a critique of the histories that have been written demonising this once radical form?

Fig.6

Nick Ut

The Terror of War 1972

© Nick Ut

The death of photojournalism may just be one of those myths, much like the end of work and the promises of free trade, which Sekula also sought to counter. In fact, its codification coincides with the production of Waiting for Tear Gas. It was in the late 1990s that photographers, both new and seasoned, were forced to confront the fact that the page was no longer the means for circulating their work. This was not, as we have come to believe or have been told, simply because the screen replaced the page as the site for the circulation of news. It was because mainstream magazine editors radically reshaped the organisation of the news on the page and in print. Instead of publishing lengthy photo-essays offering extended, in-depth and multiple perspectives on war and famine, the subjects of much of the 1990s news cycle, they circumscribed editorials around one or two iconic shots.17 Even old wars, including the last war to be narrated in essay form, the Vietnam War, were recast around a few ‘singular’ photographs. The Vietnam War came to be represented through, for example, Eddie Adams’s harrowing photograph from 1968 of police chief General Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Viet Cong suspect and Nick Ut’s shot of Kim Phuc Phan Thi running naked down a road following a napalm attack on her village in 1972 (fig.6). Photo-essays by Akihiko Okamura, such as the fourteen-page, seventeen-photograph essay accompanying ‘A Little War, Far Away – and Very Ugly’ which ran in the 12 June 1964 issue of Life, disappear in the face of Larry Burrows’s cover shot of the single, stalwart solider (fig.7).18

Fig.7

Larry Burrows

Cover of Life, 12 June 1964

© LIFE Magazine

Photo © Larry Burrows

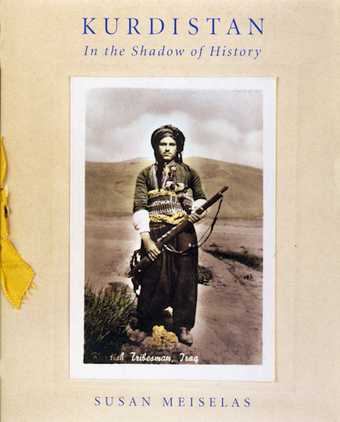

Photojournalism did not die in the 1990s, nor was it necessarily outmoded by new technologies, be they television or the internet. Rather, it was revamped or reshaped into a form more conducive to the myths of neoliberalism. As art historian Julian Stallabrass argued in his study of the emergence of the ‘fine art of photojournalism’, also a 1990s phenomenon, extended essays narrating war and famine did not ‘suit’ the neoliberal narrative that history was over and capitalism was triumphant.19 In turn, photojournalists, many consciously, left the page behind, turning instead to the walls of the museum or the pages of books to circulate their production. Sebastião Salgado’s Workers: Archaeology of the Industrial Age (1993), Gilles Peress’s Farewell to Bosnia (1994) and Susan Meiselas’s Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History (1997) (fig.8) are just a few varied and significant examples of such publications.20 In short, in the 1990s photojournalism actually bloomed or boomed only to be rebranded, especially by those on the left and in academia, as synonymous with spectacle culture and a retrogressive modernism.21 Few, in other words, have historicised the form. Much like documentary it is simply characterised disparagingly as authored, museological and humanist.

Fig.8

Cover of Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History by Susan Meiselas, New York 1997

© Susan Meiselas

The death of photojournalism may be a myth, but it still buoyed the definition of photojournalism as synonymous with the iconic shot. Notably, we see this nowhere more clearly than in the media response to the protests in Seattle. This is not simply because the same iconic shots of violence saturated the mainstream news – shots of either police or fringe anarchist (black bloc) violent actions (see, for example, the photograph printed in the Seattle Times showing ‘protestors’ smashing a window; fig.9). It is because the protestors’ response to the mainstream news explicitly countered this one-dimensional coverage. A case in point was the organisation of the Independent Media Center (Indymedia.org), a grassroots media network established in 1999 for the purpose of providing coverage of the Seattle protests. As noted on the Center’s website, ‘The Independent Media Center is a network of collectively run media outlets for the creation of radical, accurate, and passionate tellings of the truth’.22 The site, which also produced a newspaper and hundreds of hours of audio segments distributed on the web, acted as a clearing house for a wealth of information about the protest and ‘the battle’. In short, it operated in direct opposition to the top-down, hierarchical structure of mainstream media outlets. The myth of the death of photojournalism and its simultaneous spectacularisation has, in other words, been incredibly generative. It fostered the birth of citizens’ journalism, the explosion of new democratic forms of recording and telling the news. Not despite but because of the neoliberal revamping of the media, individuals can now make, record and circulate the news.23

Fig.9

Unidentified photographer

Photograph published in Lynda V. Mapes,

‘Five Days that Jolted Seattle’, Seattle Times, 29 November 2009, accompanied by the caption: ‘WTO protesters kick out windows on Pine Street downtown. Most demonstrators were peaceful, but a small group of self-described anarchists took advantage of the chaos and turned to destruction.’

It is easy to imagine that Sekula would have supported these new media platforms and promoted the proliferation of the news through collective and grassroots organisations. Yet Waiting for Tear Gas offered a wholly different response to the mainstream mythologies. Sekula worked alone, in his studio and with analogue technologies24 . He also circulated his work, for the most part, in books and museums or galleries. The work’s institutionalisation in no way mitigates its charge – its anti-photojournalism. Still working with the essay form, still working on photography’s institutionalisation as mass media, Sekula did not embrace, in order to reject, the new, old history of photojournalism as iconic. He produced a different history of media. This history, like his work, begins in the 1970s and not the 1990s. It begins when the pages of magazines, even those magazines wholly associated with corporate culture and cultural imperialism such as Life, could be read counter-culturally and critically. As numerous historians of journalism have argued, the television did not simply replace the page in the 1970s, such that the collapse of Life cannot be accounted for through histories of technological innovation. The magazine’s end was inseparable from corporate capital and the state’s response to the fact that the news coming out of Vietnam – on the page and through the screen – had a remarkable and negative impact on public support for the war.25 As the journalist Robert Elegant famously stated, ‘For the first time in modern history, the outcome of a war was determined not on the battlefield, but on the printed page and, above all, on the television screen’.26

Although there has been much debate about whether or not the circulation of photographs and footage from the war zone instigated the change in public support for the war effort or simply confirmed it, the photographic representation of violence in the mainstream media altered the future of photojournalism. Iconic images ruled, but that was not all: with the first Gulf War (1990–1), US policy was to keep photographers as far as possible from the battlefields. This ‘screen war’, to borrow the term used by media theorists Paul Virilio and Jean Baudrillard, in turn, ‘never happened’.27 By the second Gulf War (2003–11), photographers were embedded with troops and signed contracts stipulating what photographs could be published.28 Television was merely the scapegoat, not the means to a so-called end of photojournalism.

Unlike many on the left and working in new media, Sekula did not negate the myths about photojournalism or protest. He did not seek to provide new truths – to set the record straight about what actually happened in the streets of Seattle. That is, with his sequences of eighty-one slides, he did not tell another or other stories, the task of the citizen journalist and the independent media organisations that multiplied online in the wake of the Arab Spring (2010–12) and of the emergence of the Occupy movement in 2011. He re-told the same story – the myth – differently. He looped the media.

Fig.10

Allan Sekula

Two, three, many…(terrorism) 1972

© Estate of Allan Sekula

Evocative here is another photo-essay Sekula finished the year Life stopped printing: Two, three, many…(terrorism) 1972 (fig.10). Made up of six photographs of an Asian-looking man dressed in then stereotypical Vietnamese garb – he is wearing a conical hat and toting a toy machine gun – this essay is Sekula’s response to the war’s mediation.29 Its title is derived from the famous line in Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevera’s 1967 ‘Message to the Tricontinental’, in which the Argentine Marxist and key figure in the Cuban Revolution calls for ‘more’ Vietnams.30 Speaking to members of the Organization for the Solidarity of the Peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America about the dramatic rise of US imperialism around the world, Che ‘brushed history against the grain’. Instead of calling for an end to the violence, he called for more fighting and more collective action. More revolution was necessary, Che argued; more struggle against imperialism needed to be enacted, supported and recorded. If in Waiting For Tear Gas Sekula simultaneously gave us the stereotype of protest and dissolved that stereotype in a sea of bodies, in Two, three, many…(terrorism) he comically exaggerated the stereotype of the guerrilla fighter in order to remind us vis-à-vis Che that the war in Vietnam still went on unseen. The young man dressed up enacting war manoeuvres in La Jolla, California, around suburban golf courses and swimming pools, is hidden in plain sight.31 He disrupts nothing, and no one in Sekula’s photographs seems to notice him. As Martha Rosler argued in her seminal study of the way in which war is mediated, Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful 1967–72, war takes place at home and without much disturbance (fig.11). This is not simply because it is beamed into the home through the television screen or flipped through in the pages of the glossy magazines. It was because, as Rosler’s photomontages of photographs from the field and of suburban homes animates, the military–industrial complex produces, simultaneously and necessarily, the private home and more Vietnams. Sekula does not disrupt or correct the blindness; he re-enacts and reproduces it. As in Waiting for Tear Gas, in much of his work Sekula examines, meta-critically, the way media works. This is a form of photojournalism.

Fig.11

Martha Rosler

Tract House Soldier from the series House Beautiful: Bringing Home the War c.1967–72

© Martha Rosler, Mitchell-Innes & Nash

The subject of Sekula’s critique is not photojournalism, but rather the histories we have narrated about photojournalism. More precisely, Waiting for Tear Gas reminds us that not thinking and working historically, not working against the grain, may just account for the triumph of photojournalism’s sensationalism. Sekula’s appeal to the essay, like his appeal to the slide and analogue technologies, is not nostalgic: by taking up these outmoded forms of display and distribution, he drives home the point that like the stories we tell ourselves about the end of photojournalism, the stories we tell ourselves about globalisation fetishise technology. We hear that television trumps the page, and the internet outdoes, even undoes, televisual news. Yet neither story gets us to the core of the matter – namely that technology does nothing and that left-wing politics does not have a single form. For Sekula, as for Benjamin, brushing history against the grain required taking stock of the exhilarating as well as the destructive uses of media. Forms of representation do not die or disappear, but are killed off, co-opted and sold as yesterday’s news. Likewise, they are – or can be – re-imagined and re-used. The politics from below driving Waiting for Tear Gas, in short, is embedded in a grasp of history, not a photographic form or technology.