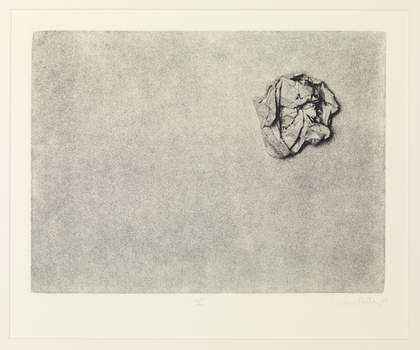

Fig.1

Liliana Porter

Wrinkle 1968

One of ten photo-etchings on paper

Image, each: 216 x 186 mm

Tate P13236

© Liliana Porter

As an Argentine artist based in New York for most of the second half of the twentieth century, Liliana Porter’s work has reflected the dominant artistic languages of the time such as minimalism and conceptualism. Informed both conceptually and formally by these discourses, works such as Wrinkle 1968 (Tate P13236; fig.1) also constitute a critical counterpoint which, while not being overtly feminist, reveals a sensitivity to the question of gender at the core of their materiality. The gesture of crumpling a piece of paper that is employed in Wrinkle bears critical stakes that run beyond the mere recording of an action. As a valueless and mundane object, the piece of paper as it is found in pockets, jackets and overcoats also partakes in a domestic aesthetic that is often associated with the feminine. Casting light on this apparently insignificant, minor object may thus be read as the deployment of a subtle feminist agenda on the part of the artist.

Porter, who was very close to Cuban-born feminist and artist Ana Mendieta during the latter’s lifetime, talked to critic and curator Inés Katzenstein about her own understanding of women’s issues and feminism. Rejecting a blanket adoption of the term, she nevertheless explained: ‘there is an idea of the woman, which is the result of a social construct that operates according to political interests and cultural patterns. The feminist approach that most interests me has to do with revealing and questioning this construction’.1 This sensitivity to the social construction of gender roles might grant a self-reflective dimension to Porter’s artistic practice, leading one to consider Wrinkle as a critical take on the aesthetic canons of the 1960s. This is the central theme of this section, which looks at this alongside the geopolitical and gender ramifications of Porter’s practice in works such as Wrinkle.

Porter’s minimalism and conceptualism

Presented together, the different plates composing Wrinkle could form a grid that would not seem out of place in a discussion of minimalism, which was a dominant aesthetic in late 1960s New York, especially due to the success of artists like Sol Lewitt, Donald Judd and Frank Stella.2 According to art historian Rosalind Krauss, the grid participates in the modernist impulse to distance art from the imperative of storytelling. ‘[T]he grid’, Krauss writes in a 1979 essay, ‘announces, among other things, modern art’s will to silence, its hostility to literature, to narrative, to discourse’.3 This rejection of narrative would initially appear antithetical to Porter’s interest in stories and literature.4 Yet it is not only the potential grid-like structure of the work as a whole that resonates with minimalism. Each plate reveals a restrained spatial arrangement, a standardised white border and the presence of neat angles drawn by the printing press, which repeat themselves from one plate to the next, thus granting to the piece a clean-cut, orderly quality that also resonates with the clinical language of that style. Porter points to the influence that minimalism might have had on her work, but at the same time shows that she was also very aware of the ethical conundrum that the apolitical appearance and modus operandi of minimalism might constitute for Latin American artists: ‘A typical minimalist work of art would have been inconceivable, absurd, and I would even say ethically questionable, if created in a Latin American country. These artworks were very expensive to produce, and made possible by very advanced technologies’.5 If, to an extent, Wrinkle replicates the geometric, repetitive and technologically aided aesthetic of minimalism, Porter also inserts within her clean frames a monochrome narrative of man-made material degradation, in a way that could be read as an effort to undo these languages from within, employing a logic of corrosion whose stakes run much further than is initially apparent.

If minimalism was among the main trends of the art scene at the time, it has also been noted that the visual language it constructed was one of bravado and idealism that was characteristic of male artists.6 Art historian James Meyer, for instance, describes minimalism’s contemporary reception as follows: ‘Minimalist practice is said to reproduce the totalizing logic of a patriarchal capitalist order, which women artists naturally oppose’.7 Indeed, in Wrinkle Porter prefigures the future obsolescence of her work, which, like human skin, creases and loses its elasticity and lustre. It is a celebration of the imperfect and the finite that is so often absent from the works of established minimalist artists. Art historian Florencia Bazzano-Nelson states that in the 1970s ‘Porter embraced the minimalist, experimental and conceptual tendencies emerging on the international art scene as she streamlined her artistic means’, while noting that Porter’s use of a ‘highly reductive aesthetics’ was mobilised to bring ‘to our attention the poetry of the simplest of everyday objects’.8 Applying to her work a veneer of minimalist aesthetics, Porter’s work could be read as an effort to disrupt minimalism’s pretensions to formal perfection and transcendence, bringing the work back to its material properties: as an assemblage of paper and ink whose main ambition is nothing more than an attempt at generating dialogue between the author, the work and the spectator.

Similarly, in her effort to reveal the worthiness of materiality, Porter’s work arguably reflected on the language of conceptual art that was also prevalent in the 1960s. Advocates of conceptualism, such as Art & Language and the artist and theorist Joseph Kosuth, rejected the idea of art as object-based production, reflecting the comments formulated by Lucy Lippard and John Chandler in their 1968 article ‘The Dematerialization of Art’. Lippard and Chandler argued that the 1960s represented a time when ‘a number of artists [were] losing interest in the physical evolution of the work of art’, giving, instead, more weight to the idea or concept that guided it.9 One of the consequences of this move was the so-called ‘linguistic turn’, in which art was conceived as a form of language used to create ‘analytic’ proposals, and artists such as Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner and Mel Bochner often introduced writing as an integral part of their works.

Fig.2

Joseph Kosuth

One and Three Chairs 1965

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© 2017 Joseph Kosuth/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York

One of the most representative illustrations of the conceptual art developed during these years is Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs 1965 (fig.2), produced just a few years before Wrinkle, in which the artist exhibited a wooden chair, a black and white photograph of the same chair and a white panel containing the dictionary entry for the word ‘chair’. By bringing together three ‘versions’ of the same thing – a material object and two representations of it, one visual and one textual – Kosuth’s work sought to question the hierarchies pertaining to aesthetic judgements and, in particular, the idea of the artwork as a physical and ‘auratic’ object. A chair, Kosuth seems to suggest, is as much the manufactured object as its photographic replica or written definition. Similarly, the artistic gesture in the creation of this ‘chair’ proposal lies not in the confection of a unique and precious piece, but rather in the formulation of questions regarding the nature of art as a means of communication.

In this, Kosuth’s work refers to the theses of nineteenth-century linguist Ferdinand de Saussure regarding language and, especially, his understanding of words as signs. A precursor of the science of semiotics, Saussure was the first to examine the ways in which each sign is composed of a signifier (the ‘sound-image’) and a signified (the concept it represents). For Saussure, if the relation uniting the signifier and the signified was the arbitrary product of convention, the existence of such a relation was nevertheless central for meaning to emerge and intelligible communication to take place. By importing the semiotic model into the visual field, Kosuth explored the various relations that might take place between these different materialisations of the chair. In so doing, he also reasserted the idea of art as a communicative tool and analytical proposal so characteristic of conceptual art.

There is, to a certain extent, a similar process at play in Wrinkle. While not quite as explicit, Porter’s work does nevertheless contain three stages of ‘paperness’ that resonate with Kosuth’s works and Saussure’s thesis: the original paper that underwent the wrinkling process, its photographic replica and the etchings produced from the photographs and exhibited in the museum. This raises questions regarding the relational nature of the artist’s practice as the paper intervenes as a form of mute communication flowing between the artist and the viewer. While not saying anything specific – in line with Porter’s arte boludo ethos of minimising the artwork’s apparent meaning – the work opens a space for dialogue pivoting around the multiple levels of existence of the piece of paper.10 As Porter explains: ‘art helps us to think, to structure a possible language for communication amongst ourselves’.11 In this sense it would seem appropriate to situate Wrinkle in line with the kind of conceptual poetics first formulated by Kosuth that gained so much importance around the time of the work’s production.

Globalising the conceptual

At the same time, however, the proposals outlined by North American advocates of conceptual art such as Kosuth were met with some resistance on the part of artists and theoreticians, who perceived their definition of conceptual art as partial and highly reductive. Luis Camnitzer, with whom Porter lived and worked for several years, was one of the most vocal critics of this way of framing conceptual art. In 2001 Camnitzer co-curated, along with Jane Farver and Rachel Weiss, the exhibition Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin (1950s–1980s) at the Queens Museum in New York, as a platform to grant visibility to conceptualist practices from across the globe, not just the United States and Western Europe. The drive behind Camnitzer’s involvement in the exhibition was, in his words, to ‘decenter art history into local histories and put the center in its right place as one more provincial province’, thus situating it as an exercise with decolonial intentions, to use semiotician Walter Mignolo’s term.12 For Mignolo, decoloniality seeks to address and challenge the colonial undercurrents still at play in Western modernity, even in modern times when post-colonial ideas and arguments seem to have been widely accepted, at least in academic and cultural circles. Examining the Latin American context in particular, Mignolo argues that decoloniality constitutes both an intellectual and a political commitment to identify ‘options confronting and delinking from coloniality, or the colonial matrix of power’.13 The Global Conceptualism show, which featured curated sections on conceptual art from East Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, included an important contingent of Latin Americans such as the Brazilian artist Cildo Meireles and the Argentine collective Tucumán Arde.

Fig.3

Cildo Meireles

Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project 1970

Tate T12526

© Cildo Meireles

Meireles’s work in the show, Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project 1970 (fig.3), involved the artist altering Brazilian banknotes, ink-stamping them with the subversive question ‘Quem matou Herzog?’ (‘Who killed Herzog?’), which refers to an investigative journalist who had died while in military police custody in Brazil, and putting the notes back into circulation. Works like this mobilised a similar conceptual language as the one developed by Kosuth, conceiving of art as a communicative tool. Yet the main difference lay in the political commitment inherent to the Brazilian artist’s production: as the title of the series suggests, Meireles conceived of his work as a form of ‘insertion’ or implosive disturbance, using the existing flows of circulating banknotes to convey disturbing questions. Camnitzer argued in his book Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation that Meireles ‘conveyed three messages at once: in asking the question, he was challenging the dictatorship; in defacing the bills, he was altering the meaning of money by changing it from an object of value to a conveyor of information; and in using this material for an art piece, he was demystifying the art object’.14

Camnitzer’s book, which was published first in English in 2007 before being translated into Spanish, constituted an effort to expand on some of the ideas about Latin American conceptualism which the author had begun to formulate in Global Conceptualism. In it Camnitzer criticised what he viewed as the tautological nature of North American and British conceptual art, admonishing them precisely for their lack of political engagement. By contrast, Camnitzer argued, Latin American forms of conceptual art both predated their Northern hemisphere counterparts and maintained ideological – and even utopian – concerns. For Camnitzer and his fellow curators of Global Conceptualism, when Latin American artists ‘broke decisively from the historical dependence of art on physical form and its visual apperception’, it was not to turn to the metaphor of the artist as scientist or philosopher defended by Kosuth.15 Rather, they became what curator Mari Carmen Ramírez calls an ‘active intervener in political and ideological structures’.16 For both Ramírez and Camnitzer, Latin American production from the 1960s onwards constituted a neo-avant-garde that conceived of art as a tool to address questions of political authoritarianism and economic and social injustice, as well as enabling and empowering artistic languages to imagine new forms of utopia specific to the continent. Conceiving of a specifically Latin American form of conceptualism thus constituted for Camnitzer as much a revisionist exercise as a post-colonial, or decolonial, attempt to re-establish the historiographic balance. ‘The center … created the term “conceptual art” to group manifestations that gave primacy to ideas and language, making it an art style, historically speaking’, Camnitzer wrote. ‘The periphery, however, couldn’t have cared less about style and produced conceptualist strategies instead.’17

Bearing in mind the closely collaborative relationship that she had for many years with Camnitzer, it seems important to question the place occupied by Porter in this conceptualist proposal. While it may be said that many of her works harbour political concerns, the artist was never interested in turning them into explicit acts of militancy. As Porter explains, ‘[t]here are artists whose work directly addresses political issues. In my case, politics is not a theme, although it’s manifested in many ways’.18 Having said this, and although Porter does not necessarily like to have the tag of Latin American artist pinned on her work,19 a close reading of Wrinkle reveals some elements that would make the work fit comfortably with the definition of Latin American conceptual art provided by Camnitzer.

The politics of Wrinkle

Describing the rise of increasingly authoritarian military regimes in the Southern Cone starting in the 1960s, the Argentine sociologist Guillermo O’Donnell coined the term ‘bureaucratic authoritarianism’. As O’Donnell defined it in his 1973 book Bureaucratic Authoritarianism: Argentina 1966–1973 in Comparative Perspective, bureaucratic authoritarianism combined highly repressive and isolating regimes inside their national boundaries with the implementation of neoliberal capitalist economies turned to exchanges and economic partnerships with the outside. Moreover, the violence that took place in countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Chile and Uruguay during these years was very real, yet was concealed under a veneer of bureaucratic reasoning, or ‘technical rationality’.20 As an Argentine, O’Donnell specifically had in mind the corrupt military regime of Juan Carlos Onganía, who became the country’s de facto president between 1966 and 1970. In bureaucratic authoritarian states, O’Donnell wrote,

[the] regime – which, while not formalized, is clearly identifiable – involves closing the democratic channels of access to the government … Access is limited to those who stand at the apex of large organizations (both state and private), especially the armed forces, large enterprises, and certain segments of the state’s civil bureaucracy.21

Wrinkle was produced before O’Donnell’s retrospective analysis, yet it was also made two years into the Onganía dictatorship. Although when talking about her work Porter emphasises her technical interests in conceptually expanding the limits of printmaking – the idea of ‘editing a gesture’22 – Wrinkle could also be read through the prism of the bureaucratic type of state violence that was taking place in her home country at the time of its production. In this light, the image of the piece of paper that is first wrinkled, then etched and finally subjected to the flattening duress of the printing press arises as a symbol of the abuses perpetrated towards Argentine civilians during these years. Similarly, while the initially pristine state of Porter’s piece of paper might stand for the victory of the white collar and the paper trail in this new bureaucratic national order, its ultimate transformation into a piece of waste could open a more optimistic trail of interpretation, intervening as a subtle act of rebellion against state control and censorship. The piece of paper in Wrinkle is thus as much the victim as the culprit, performing its own disappearance through a contained, yet terribly determined, violence. Seen in this light, the work might therefore constitute one of the ways in which Porter mobilised a specifically Latin American type of conceptualist language to voice concerns about events affecting her country at the time.

Although there are certainly parallels to be drawn between the destruction of the piece of paper and the crises shaking the south of the continent in the second part of the twentieth century, Wrinkle does not necessarily belong to the engagé tradition of artworks that Camnitzer included in his history of Latin American conceptualism. In Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation, Camnitzer identified two central historical sources that inspired Latin American conceptualism and especially its desire to combine educational and revolutionary ambitions. One of these was the writings of nineteenth-century educator Simón Rodriguez, who was mentor to Simón Bolivar, the Venezuelan leader who contributed to the liberation of Venezuela, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Panama and Peru from the Spanish. The second was the spectacular performances staged by the left-wing guerrilla group Los Tupamaros, who were active in Argentina and Uruguay in the 1960s and 1970s. As relevant as Camnitzer’s ideas might be to understanding the historical backbone of Latin American conceptual art, they are also in discordance with Porter’s interest in recording minor, anti-heroic gestures, returning to them their humble nobility, as she does in Wrinkle. Moreover, if Camnitzer rejected the purely theoretical foundations of conceptual art, his own model equally conceived of art as a possibly dematerialised form of linguistic strategy. While Porter described her work as the act of ‘editing a gesture’, it is certainly not a casual one that the artist chose. Instead, by registering the different steps leading to the material degradation of the paper, it is the act of destruction itself that the artist sought to depict: not through any epic form of narrative but rather through a detailed focus on the stages comprising the journey. In Wrinkle, the fate befalling the piece of paper is therefore not inconsequential and the possibly empathetic response it triggers comes from the heart of the work’s materiality: that very aspect of art that both North American conceptualism and Camnitzer’s expanded definition of it sidelined in their linguistic turn and ideological ambitions.

As with her ambivalent relationship to minimalism, it therefore seems that Porter’s critical take on the kind of conceptualism defended by Camnitzer hails from a gendered – if not feminist – concern. As Cecilia Fajardo-Hill remarks in her essay in the catalogue of the 2017 exhibition Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985, when advocates of Latin American conceptualism such as Camnitzer and Ramírez included women artists in their texts, they tended to make them fit indiscriminately into their decolonial, heroic narrative of Latin American neo-avant-gardes, thus not paying specific attention to the ways in which their own approaches to conceptualism may offer a different narrative. As Fajardo-Hill states: ‘The criteria for conceptualism deployed by these authors are heroic, political, and even militant, leaving little space for those forms of conceptualism and experimental art that embrace more subjective interjections and both broad and more intimate personal and political struggles’.23 Apparently weary of the kind of triumphalist discourses that led to the articulation of colonial and post-colonial rhetoric alike, Porter seems to return to the material quality of her works to ponder what happens to those elements cast aside or marginalised by more mainstream readings of history. The crumpled piece of paper in Wrinkle might therefore come to symbolise this category of the small, the irrelevant or the quotidian that has so often been associated with the realm of the feminine. By casting her eye over the fate of these minor forms of materiality, Porter brings their existence back to the fore in a gesture that seeks to defy and challenge dominant conceptualist discourses.