Following her move to New York in 1964, Liliana Porter studied printmaking at the Pratt Graphic Arts Center in Manhattan. It was while attending the Pratt that she first met Uruguayan artist Luis Camnitzer and his friend, the Argentine painter Luis Felipe Noé. The atmosphere stirring this group of expatriate and exiled artists living in New York at the time was a particularly exciting one for Porter, who recalled ‘the sensation of being in the twentieth century, of living in the present moment’.1 Despite – or perhaps because of – this electric atmosphere, both Camnitzer and Porter quickly felt limited by the rules and norms traditionally determining the practice of printmaking. The New York Graphic Workshop (NYGW), which they co-founded along with the Venezuelan artist José Guillermo Castillo in 1964, was born out of an ambition to break away from this conservative mind-set. A labour-intensive and skill-centred process, printmaking had lingered for centuries on the border between art and craftsmanship, leading to the printmaker often being considered nothing more than ‘just an excellent technician’, as Porter has noted.2 By contrast, the NYGW aimed to emphasise the conceptual nature of the medium and downplay its manual nature by insisting on its ‘status as a multiple’, as Porter notes.3

Porter, Camnitzer and Castillo were certainly not isolated in their reformist endeavour. As Porter points out, this period saw the rise of pop art in New York, a movement that encouraged declassifying gestures and the opening up of artistic iconography to imagery from mass culture. The NYGW set out to embark on a similar journey with regard to technique, bringing to the fore a more accessible iconography and the formulation of ‘democratic techniques of printmaking’.4 In practice, Porter explains, this entailed developing a more conceptual and analytical approach to the printing process, ‘[e]mphasizing the concept rather than the technique, or, in other words, putting the technique at the service of the idea [in order to] to transcend the simple, singular category of “printmaker”’.5 Wrinkle 1968 (Tate P13236), a work produced during the years of Porter’s involvement with the workshop, reveals some of the concerns animating the artist during this period of her life. This essay shows how Wrinkle reflects the historical, aesthetic and conceptual context of the NYGW.

The workshop’s ethos

As a collective endeavour, the NYGW sought to redefine the practice of printmaking, setting it free from what the workshop’s founders perceived to be the stifling conservatism that constrained the medium. Experimenting materially and formally with the limits of both the printing press and paper, the workshop’s ethos also voiced a form of institutional critique, creating works that were resistant both to contemporary art market values and to the established politics of exhibition. While the NYGW now features as an important episode in the history of conceptual art in New York, it initially emerged out of the diverse origins – and, to an extent, the outsider status – of its founders.6 As Camnitzer recalls, ‘We were sensitive to the pressures of New York and ready to do anything to join a good gallery, but we had also brought the periphery with us and we maintained our Latin American perspectives and commitments’.7

In their inaugural action in 1964, the NYGW published a manifesto that outlined some of their ambitions, including their goal to be ‘conditioned but not destroyed by our techniques’.8 The collective also theorised the conceptual backbone of their project by coining the notion of the ‘FANDSO’: the ‘Free Assemblable Non-Functional Disposable Serial Object’. For the members of the workshop, FANDSO constituted a rallying cry for printmakers to adopt new approaches to their own materials and techniques; Camnitzer has described this as an effort ‘to transcend a craft’.9 The manifesto that the artists issued was sent to various recipients – ‘members from the art world, friends and public in general’10 – accompanied with a cookie that the artists had baked especially for that purpose, which accounts for why this inaugural statement became known as the ‘Cookie Manifesto’. This humorous approach would constitute a characteristic trait of the collective and also resonates with the witty tone palpable in Wrinkle itself. At the same time, the principles outlined in the text accompanying the cookie reflected a serious ambition to inject new blood into the fine art branch of printmaking. ‘The printing industry prints on bottles, boxes, electronic circuits, etc. Printmakers, however, continue to make prints with the same elements used by [Albrecht] Dürer [1471–1528]. The act of printing in editions, the act of publishing, is more important than the work carried out on a printing plate’, they wrote.11

In the workshop’s collaborative space, the application of these foundational principles led to the production of works that experimented materially with the printing press by printing on a ream of paper, for instance, or by incorporating heterogeneous materials such as textile, wood or glass. At the same time, their practice expanded beyond strictly technical experiments and towards the formulation of new types of artistic language, such as mail art. By exploring the existing channels – and constraints – inherent to the postal system, mail art offered the possibility of a trans-border circulation of artworks, and it is thus certainly not coincidental that this appealed to artists hailing from or active in countries ruled by authoritarian regimes.12 In practice, it also carved out a space of personal artistic freedom, since in its material paucity and humble economy of display it represented the opposite of Porter’s view of the United States as ‘the epitome of waste and excess’.13

‘To be wrinkled and thrown away’

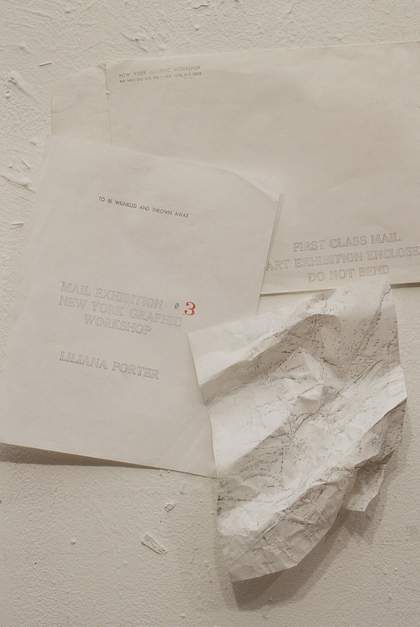

Fig.1

Liliana Porter

To Be Wrinkled and Thrown Away 1969

© Liliana Porter. Courtesy the artist

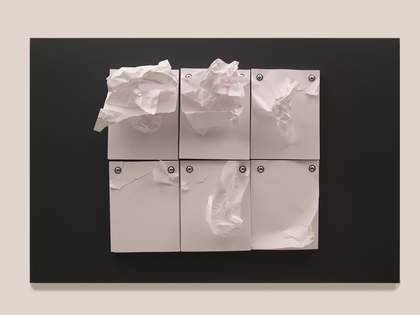

In 1969 Porter produced a mail art intervention that entailed sending a piece of blank paper in an envelope to random recipients (fig.1). Along with the paper came the written instruction ‘To be wrinkled and thrown away’, situating the work in relation to a Fluxus conception of the art object as a potential action ‘in kit’ – a set of instructions to be read and performed.14 Although it is not entirely clear whether Porter’s mail art piece was made before or after Wrinkle, the former could nonetheless be read as prefiguring the latter: To Be Wrinkled and Thrown Away makes a conceptual proposal that could have led to the production of Wrinkle had one of the recipients decided to follow the instructions step by step and record them through printmaking. Both works were produced in a period of two years (1968–9) during which the artist experimented extensively with the gesture of the crumpled piece of paper, exploring it in different media. As well as being the year in which Porter’s wrinkled environments were installed at the Museo de Bellas Artes, Santiago, and the Museo de Bellas Artes, Caracas, 1969 was also when Porter and Camnitzer exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, as part of their artistic fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania.15 At the Institute of Contemporary Art Porter returned to the display format she had previously explored in Santiago, exhibiting small, wall-mounted pads of paper from which visitors were invited to tear away and crumple full sheets or portions of them (fig.2).

Fig.2

Liliana Porter

To Be Wrinkled and Thrown Away 1969

Installation view at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, Philadelphia, 1969

Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zürich

© Liliana Porter. Courtesy the artist

Bearing in mind the theoretical principles that led to the establishment of the NYGW, it could be argued that Wrinkle combined two of the central elements animating the workshop: an ambition to use printmaking in a more conceptual way – ‘editing a gesture’, as Porter puts it16 – and a critique of the economy of excessive consumption that characterised the culture of the United States in Porter’s view. The mail art piece and its instruction to discard it also carried an implicit criticism of the art market and its speculative interest in art as investment. Rather than admiring, cherishing, framing and profiting from the artwork, Porter’s work instructed the recipient to proceed in the exact opposite way: to wrap both aesthetic and market values into one crumpled ball and get rid of it, at once.

There seems to be an inherent contradiction between the 1969 mail art piece and Wrinkle, however. Indeed, if one were to conceive of the former as a precedent for and a prefiguring of the latter, then Wrinkle could be seen as a blatant transgression of the artist’s initial injunction to discard the piece of paper. While To Be Wrinkled and Thrown Away hailed from a desire to disrupt the mechanism of aesthetic pleasure upon which the economic and institutional circulation of the artwork thrives, Wrinkle does not shy away from visual seduction; on the contrary, it is attractive as both a conceptual proposal and a beautiful object, one that has returned to the comfort of the two-dimensional format.

This apparent paradox reflects the way in which the FANDSO agenda that guided the production of the NYGW evolved and took on different meanings throughout the years. As Camnitzer remarks, although FANDSO started as an appeal to artists to produce works that rejected material longevity in order to resist institutionalisation, it became progressively more inclusive, embracing the possibilities offered by works whose material existence was not explicitly antagonistic towards the institution but could be autonomous enough to do away with those institutions’ frameworks.17 Paraphrasing Castillo, Camnitzer explained how ‘Castillo came up with the notion of a “super-object”, a product that would be able “to function in the daily context without the need of a traditional frame or reference (museum-book) and that would affect the context by its own and absolute presence”’.18 This idea triggered such enthusiasm on the part of the collective at the time that they even toyed with the idea of renaming themselves the New York FANDSO Super-Object Workshop.19 Although Porter’s Wrinkle was produced one year prior to this, the way in which the work foregrounds the poetic potential of the material object certainly appears to prefigure this new orientation in the collective’s ethos.

Fake exhibitions and fictional identities

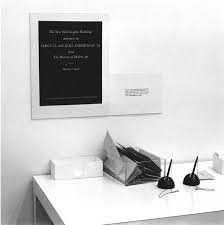

Fig.3

New York Graphic Workshop

Untitled 1970

Mail art installation at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1970

© Liliana Porter. Courtesy the artist

The NYGW’s best-known work might be the one they produced for the now-iconic show Information, held in 1970 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York. For their contribution to the exhibition the artists assembled a display that advertised a fake show of mail art (fig.3). Putting pens and envelopes at the disposal of the audience, they invited them to leave their names and addresses should they wish to receive a copy of the displayed poster that stated ‘The New York Graphic Workshop announces its First Class Mail Exhibition ’14 from The Museum of Modern Art’. Visitors who left their contact information later received a copy of a poster that was the same as the exhibited version in all respects except that the word ‘announces’ had been replaced by ‘announced’. The work not only introduced the notion of time and duration, central to Porter’s own production; it also summarised the attitude adopted by the collective with regard to art institutions. By advertising a fake exhibition, and making that exhibition the advertisement itself, the NYGW poked fun at the sacrosanct status of art shows taking place in established venues such as MoMA. At the same time, by making the museum bear the postage cost of sending all of the posters to the interested parties, they also plotted a minor, yet symbolically loaded, campaign to impact the museum’s finances.

This mixture of humour and political critique can also be found in the NYGW’s take on the art market and the artificial value assigned to artworks. One way in which they communicated this was through the production of works whose technical properties (as outlined at the beginning of this section) made them resistant to the speculative logic of art collecting that relied on material, collectable objects. Another entailed the denial of creative authorship by inventing a fictional artist whom they called Juan Trepadori. The artists imagined a colourful life for Trepadori, painting him as a disabled autodidact from Latin America whose whereabouts were unknown. Trepadori would create artworks that suited the dominant tastes of the time and the artists would sell his productions to collectors, never revealing the fictitious nature of the artist’s identity.20 Started as a joke, Trepadori also became an alternative source of income for some artist friends of the workshop in need of instant cash: ‘any friend who came by and needed money would make a Trepadori. The work would sell and the artist would win their little Trepadori grant’.21 The benefits of the invention of this creative avatar were therefore double: not only did it play a trick on the art market by interfering with its cherished reliance on provenance, but it also allowed artists to earn money without having to adapt their own production to the requirements of dominant taste. At the same time, the Trepadori project became a sort of stylistic exercise for artists who found in it an unsuspected pleasure, as Porter observes:

He [Trepadori] was a basically derivative, not at all brilliant, artist who, curiously, gave the artists who participated in the enterprise the freedom to create without pressure and to experience an unprecedented, almost unspeakable kind of pleasure.22

Taken as a whole, these works – whether produced individually or collectively – sought to attack the very foundations of institutions and their self-granted authority in validating or rejecting what can qualify as art. This was particularly visible in the works of Camnitzer, whose output – as an artist, writer and educator – has always maintained a strong element of institutional critique. As Porter summarises, ‘José [Castillo] was marvellous but totally skeptical: he believed that the thing was meaningless; for me, the issue was not to determine if it had meaning but to invent the meaning; and Luis [Camnitzer], of course, believed that it did have meaning, and so he theorized and wrote about it’.23

These differences might also point to the root of the issue that led to the disbanding of the NYGW, shortly after their participation in the MoMA show. Castillo, who had maintained a professional career on the side, accepted employment in the literature office of the Center for Inter-American Relations (now the Americas Society). Porter and especially Camnitzer had always been particularly critical of the Center’s passivity in the face of the democratic crisis affecting the southern part of the continent at the time, and in 1970 they joined a group of Latin American artists who arranged a boycott of the organisation. Their friend and partner’s acceptance of this job therefore led to a distancing between the artists and brought the NYGW to a close.24

Poetry and process

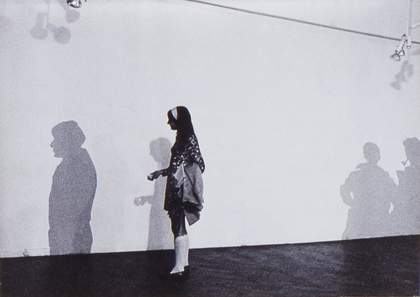

Fig.4

Liliana Porter

Untitled Shadows 1969

Installation view at Instituto Torcuato di Tella, Buenos Aires, 1969

© Liliana Porter. Courtesy the artist

Returning to Porter’s individual production during her time as a member of the NYGW, it is important to point out that if a work like Wrinkle does illustrate, as argued previously, some of the technical and conceptual concerns animating the collective in those years, it also bears witness to a poetic sensitivity that comes through in the subtle beauty emerging from the material’s self-declared precariousness and its multiple nature. Through its ambition of ‘editing a gesture’, as Porter puts it, Wrinkle emphasises the manual quality of the intervention in a way that goes beyond the conceptual.25 Indeed, the fragmentation of the wrinkling gesture into individual printing plates slows down time, allowing specific attention to be paid to the process itself.

This poetic concern also came through in a series of works that Porter produced around the same time as Wrinkle. Invited to participate in the 1969 group show Experiences 69 I at Buenos Aires’s Instituto Torcuato di Tella, an important venue for avant-garde and experimental art in Latin America at the time, Porter decided to adorn the gallery walls with human shadows in the form of her Untitled Shadows series, made that same year (fig.4). Produced as silkscreen prints, the grey shadows looked very realistic, triggering what the artist describes as a ‘wonderful perceptual confusion’ among the visitors, especially on the opening day when, through a clever lighting setup, the ghostly forms appeared to mingle and communicate with the shadows that the ‘real’ visitors cast on the walls.26 Porter’s interest here lay in representing absence or, as she puts it, ‘to create absences, because those painted shadows were perceived as real shadows of people that were not there’.27

Fig.5

Liliana Porter/New York Graphic Workshop

Shadow for Two Olives, from Mail Exhibitions 1969

Prints and envelopes posted out from Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, Buenos Aires, June 1969

© Liliana Porter

As part of her participation in the Torcuato di Tella exhibition, Porter also produced a mail art intervention under the name of the New York Graphic Workshop. Drawing from the host venue’s mailing list and her own contacts, Porter sent an envelope to various recipients that contained four printed cards. Each card featured a reproduction of the shadow of an object that, as with the human silhouettes, was not materially present nor represented on the paper: the silhouettes of a glass, a bus ticket, the bent corner of the paper itself and a pair of olives (Shadow for a Glass; Shadow for a Bus Ticket; Shadow for a Bent Corner; Shadow for Two Olives, all 1969; fig.5). As the artist explains: ‘the first thing that existed was the printed shadow that you received by mail, and then the person who received the postcard, if they wanted, might place the olive, the glass, or the bus ticket on top of, or next to, the shadow’.28 As well as playing with presences and absences, this work therefore also involved the inversion of time, producing a work that offered the trace of the object without the object itself, and leaving open to the recipient the possibility of ‘completing’ the piece.

This conception of the work as a still-provisional action that requires the intervention of the recipient or audience in order to reach completion resonates with Porter’s To Be Wrinkled and Thrown Away, while remaining open to the possibility of its material existence as an artwork, as Wrinkle also does. Meanwhile, these pieces also testify to the artist’s reluctance to have her works assigned to a specific genre or category, placing them at the threshold between the print, the conceptual action conducted by the artist and the performance by the recipient of the piece, following the artist’s instructions.