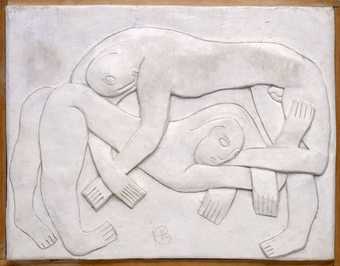

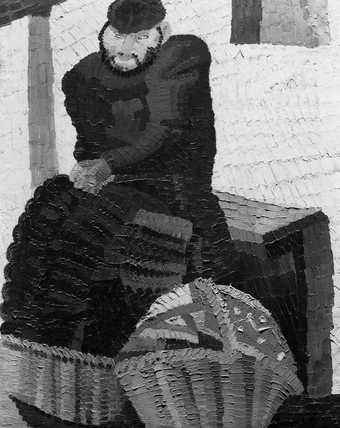

Fig.1

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Wrestlers 1914, cast 1965

Tate

Henri Gaudier left his native France in 1911 in search of work as an artist and to avoid military service, then compulsory for young men. He arrived in London with his Polish partner, Zofia – or in anglicised form, Sophie – Brzeska. They did not marry but lived together, often describing themselves as brother and sister to others, and unusually combined their names to form the surname ‘Gaudier-Brzeska’. It was under this name that the sculptor exhibited and signed his work, and his friends, patrons and colleagues generally referred to him by this name, or sometimes simply Brzeska.

Gaudier-Brzeska had a precocious talent but he did not attend art school and was largely self-taught as an artist, aside from some evening classes in drawing. He led an impoverished existence but was in contact with leading avant-garde figures including the poet Ezra Pound, the sculptor Jacob Epstein (both of whom were American), the painter and writer Wyndham Lewis and the art critic and painter Roger Fry. He lived in London until he returned to France in 1914, aged twenty-three, to enlist in the French army. An infantry sergeant, he was killed fighting in the trenches in northern Franceon 5 June 1915. Many friends, especially his close ally Ezra Pound, mourned the brevity of his career, observing shortly after the sculptor’s death, ‘we have lost the best of our young sculptors and the most promising. The arts will incur no worse loss in the war than this is.’1

Pound directed the posthumous critical reputation of Gaudier-Brzeska as a sculptor at the vanguard of European modernism, killed before reaching the prime of his career. He published his Memoir of the sculptor in 1916 and organised the Gaudier-Brzeska Memorial Exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in London in 1918. Other memoirs and biographies were released in the 1920s and 1930s, most notably Jim Ede’s book Savage Messiah (1930 and 1931), blurring the realities of Gaudier-Brzeska’s career with myths and legends and creating from his life something of a ‘bohemian melodrama’, according to the art historian Evelyn Silber.2 These accounts coincided with a wave of interest in Gaudier-Brzeska’s work by a new generation of sculptors such as Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Frank Dobson, who were drawn to Gaudier-Brzeska’s technique of carving directly into stone, wood, plaster and other materials. While the Frenchman’s reputation has rested largely on his stone carvings, in recent years art historians and curators have returned to Gaudier-Brzeska’s small but impressive output of sculptural works in a range of materials including plaster, wood, bronze and brass, as well as his drawings and a handful of paintings and texts written for the leading avant-garde journals of the time. The focus of this project, the carved plaster relief Wrestlers (fig.1), throws new light onto the innovative ways in which he experimented with sculptural materials at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Uncertainty surrounds the dating of Wrestlers. Some experts believe on formal grounds that the carving must have been made in 1913, but Gaudier-Brzeska included the work in his handwritten ‘List of Works’ under 1914 as ‘lutteurs, bas relief, modelage directe en plâtre’ (‘wrestlers, bas relief, modelled directly in plaster’).3 Pound also recalled seeing the finished version of the relief on one of his visits to the artist’s studio in Putney, west London, in 1914 while he was having his portrait bust carved (figs.2–3):

An infant Hercules in grey stone had been broken in moving to this studio. The head rolled about the floor, a round object about half the size of a fist, it was one of the kitten’s playthings. There was the large bas-relief of the wrestlers, some old work in one corner, the small forge, a representational bust, clay, in the manner of Rodin which he had, thank Heaven, discarded.4

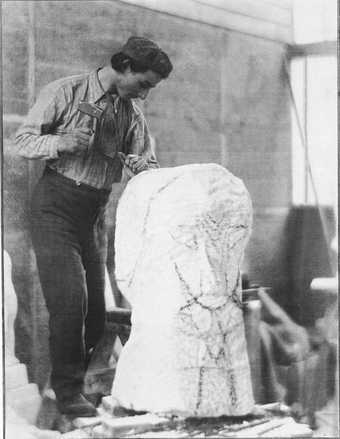

Fig.2

Walter Benington

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska carving Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound c.1914

Photo: Benington archive

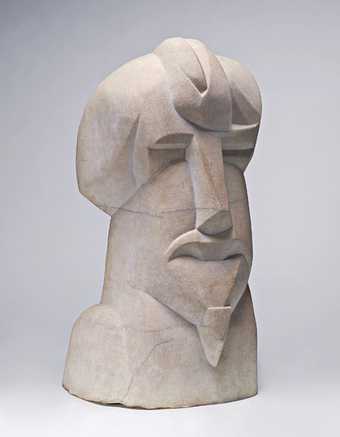

Fig.3

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound 1914

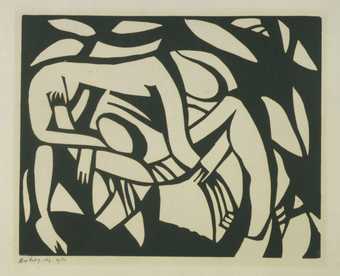

Fig.4

Fig.5

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

The Wrestlers 1913

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Although offering no precise information about the work’s date, another friend of Gaudier-Brzeska, the artist Horace Brodzky, also wrote about Wrestlers. In his memoir of Gaudier-Brzeska, published in 1933, Brodzky described its genesis and early construction:

At the beginning of our friendship, in addition to carving and modelling, he was also painting in oils, and making pastels, drawings and etchings. At this time he showed me a painting of a Whitechapel Jewish fruit-seller. It was painted with anything but an economy of paint. In fact he must have had Van Gogh in mind, and he applied the paint in an extravagant manner. The painting displeased him and one evening at his studio I was asked to scrape it down. I then reversed the canvas on the stretcher. On my next visit I noticed that he has commenced to paint an imaginative tropical landscape, hot in colour, with a dull red sky and exotic trees, all very Gauguinesque. This also displeased him and was later abandoned, and the canvas was covered with a thin coat of plaster. On this Brzeska carved two wrestling figures … This subject was one that he used more than once. He made drawings of the subject, also a lino-cut [fig.4].5

Conventionally, plaster is used in the preliminary stages of making a sculpture, for example, the construction of plaster moulds used in the bronze-casting process or the fashioning of maquettes. Gaudier-Brzeska, however, frequently used plaster for finished pieces of work, even ones on a large scale.6 His reasons were largely economic: household plaster was cheap and easily available. Gaudier-Brzeska’s poverty was frequently remarked upon by his contemporaries: he lacked money not only for materials but also for daily necessities. For a sculptor who often resorted to stealing bits of stone from cemeteries or waiting for off-cuts from his studio-neighbour Aristide Fabrucci, sourcing a flat piece of stone for Wrestlers was out of the question. However, plaster also possesses qualities that are ideal for the untrained sculptor. Until this point Gaudier-Brzeska had predominantly modelled in clay but wanted to learn how to carve in the manner of sculptors he admired such as Jacob Epstein in London and Constantin Brancusi in Paris. Under the sharp edge of the chisel, plaster came away easily. This allowed Gaudier-Brzeska, who had not been to art school or served an apprenticeship with another sculptor, to experiment with the skills and processes needed to carve directly into the material in a way that the resistant surfaces of stone did not.

Fig.5

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

Portrait of a Whitechapel Jew c.1913

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Using the canvas with the painting Whitechapel Jew on one side (fig.5), Gaudier-Brzeska built up a plaster slab and then carved into it, cutting, chipping and chiselling away at the dried plaster to create his fighting figures in relief. He was in good company: the sculptor who had provoked Gaudier-Brzeska into first taking up the chisel, Jacob Epstein, had also created a relief sculpture when he first carved directly with the chisel, as had the letter-cutter-turned-sculptor Eric Gill.7 Shortly after coming to London, Gaudier-Brzeska had sought out Epstein and met with him in his studio. In his Memoir Ezra Pound recounted an anecdote of this important, career-making moment. Epstein, who mustered ‘the thunders of god and the scowlings of Assyrian sculpture into his tone and eyebrows’, demanded of the young sculptor, ‘UMMHH! Do … you cut … direct … in stone?’ ‘Most certainly!’ replied Gaudier, who had never carved into stone before but could not bring himself to admit this to Epstein, especially in a studio dominated by a huge block on Portand stone that Epstein was shaping into the tomb for the poet Oscar Wilde in the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.8 Gaudier-Brzeska may not have met Eric Gill in person but saw carvings by Gill exhibited at the Chenil Gallery in London in 1914.

Once satisfied with the result of his labours, Gaudier-Brzeska carved his monogram in the centre of the empty ground underneath the fighting wrestlers. There was no more scraping down or layers, and no need to reverse the support in order to add other materials. The work was, for the time being, finished. Wrestlers remained in the studio after it was completed. In Gaudier-Brzeska’s ‘List of Works’ the columns where he added the price the work was sold for and the name of the buyer remain empty in the case of this piece. But it might be that the work was not made to be sold and that it was a work done for personal interest, to test out an idea. Wrestlers left Gaudier-Brzeska’s studio for the first time in 1918 when it was exhibited at the memorial exhibition of his work held at the Leicester Galleries in central London.9