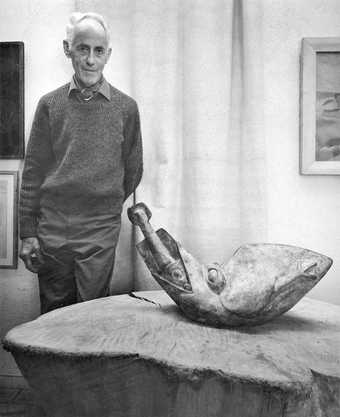

Fig.1

H.S. Ede at Kettle's Yard

Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge

H.S.[Jim] Ede is best remembered as the creator of Kettle’s Yard house and gallery in Cambridge (fig.1). However, before he and his wife Helen bought the house in 1957, Ede had a very active career as a curator and writer. He worked as an Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery (it was officially called the National Gallery of British Art until 1932), resigning in 1936 to relocate to Morocco where he lived until 1952.1 It was through his job at the Tate Gallery that Ede had his first, and by all accounts, inauspicious encounter with Gaudier-Brzeska’s work. He recalled that a ‘great quantity’ of it was

dumped in my office at the Tate: it happened to be the Board room and the only place with a large table … It had become the property of the Treasury, and the enlightened Solicitor General thought that the nation should acquire it, but no, not even as a gift. In the end I got a friend to buy ‘Chanteuse Triste’ [Singer 1913, fig.2] for the Tate, I subsequently gave three to the Contemporary Art Society, and three more to the Tate. It took some doing to persuade them to accept even this, and the rest, for a song, I bought.2

Letters in the Tate Archive between Ede and Norman Reid, director of the Tate Gallery in the 1960s, document how the cast of Wrestlers entered Tate’s collection. In February 1966 Ede wrote to Reid saying that he would be willing to donate a number of the Gaudier-Brzeska works he owned if the ‘Board of Trustees ever consider forming a permanent Gaudier-Brzeska room’.3 He listed the following works:

Seated Woman bronze

Wrestler relief herculite

Maternity bronze

Garden Ornament bronze

Head ‘stone’

Doorknocker bronze (small)

Duck bronze (small)

Monkeys ‘stone’ (small)

Relief Head bronze (small)

Dog bronze

Mermaid bronze

Ede whetted the director’s appetite for this collection, adding ‘they could form a splendid collection, considerably larger than the one set up at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris’ and that he would ‘amplify’ Tate’s collection of Gaudier-Brzeska drawings. Ede was keen – almost to the point of obsession – for Gaudier-Brzeska’s work to always be on display in a national collection in Britain. He cautioned Reid that he did not want to

make these gifts if owing to lack of space these would have to be put into store. The room in Paris is so beautiful & so much appreciated that the Tate might well care to have a similar room – I’m not sure that it must be a room – a large alcove perhaps being more suitable … I consider the value would be about £25000.4

After a meeting of the Board of Trustees, Reid wrote to Ede with bad news. Declining Ede’s ‘handsome’ offer, Reid appealed to Ede’s knowledge of the Tate from his former days as an employee, saying:

You may remember from your own days here how reluctant Trustees are to accept conditions regarding exhibition with any work of art and I am afraid that this proved to be the case with your own projected gift, which was discussed at considerable length by the Trustees at their meeting last Thursday. There are, I believe, only three objects in the whole collection which have conditions of exhibition attached to them and two of these were inherited from the National Gallery. I am sorry if this sounds very ungracious but this was the decision arrived at by the Trustees.5

After several more letters back and forth, Ede decided to offer his gift without any conditions concerning its display. This was accepted by the gallery’s Board of Trustees on 17 March 1966. It was stressed to Ede that the gallery would ‘try to show them as a group whenever possible and … do Gaudier-Brzeska the full justice he deserves’.6

Ede kept a close eye on the display of his gift at Tate. A year later he wrote to Reid, obviously very aware that he might be trying the patience of a busy gallery director:

Yes I know I’m a pest, and I’m sorry – but feel I must write. Is there any near prospect of having more things by H. Gaudier-Brzeska’s work shown in the Tate? I believe that at present there is only Redstone Dancer & Bird Swallowing a Fish & I feel it such a shame when so many students & Directors of Galleries abroad come & express disappointment.7

Ede was one of Gaudier-Brzeska’s most ardent supporters, although they had never met. Ede’s gift to Tate and his gift of his collection at Kettle’s Yard to the University of Cambridge contributed in important ways to the establishment of Gaudier-Brzeska’s reputation as one of the most significant sculptors in Britain at the beginning of the twentieth century. In an accompanying essay to the 2011 republication of Ede’s important book of 1930–1 Savage Messiah: A Biography of the Sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (which Ede compiled from the papers he acquired from Sophie Brzeska’s estate),8 curators Sebastiano Barassi and Jon Wood described Ede’s championing of Gaudier-Brzeska’s work as inspired by his ‘confidence in the value of Gaudier-Brzeska’s work, coupled with a sense of ambition and responsibility for it’ that continued throughout Ede’s life.9 Ede saw Gaudier-Brzeska as an international artist (‘perhaps the most vital of his epoch’ was Ede’s estimation in 1984)10 and he might have envisioned his gift as expanding the nation’s collection to include a more diverse range of foreign artists, as had been recommended as far back as 1917 in the Curzon Report, which made Tate responsible for housing the nation’s collection of modern international art. To promote Gaudier-Brzeska’s reputation as widely as possible, however, Ede made gifts to collections across the world in the 1950s and 1960s, including ones in France, Scotland, the USA and Germany, and to universities in the UK (Essex, Warwick, Manchester and Sheffield).