Recent exhibitions in Britain and the United States have rekindled an interest in Victorian art and aesthetics. However, for many years Victorian sculptures such as Edward Onslow Ford’s The Singer were distinctly out of fashion. This may in part explain the past history and treatment of this sculpture. The Singer is an example of a highly ornate aesthetic, but for years the colour of the surface and fine ornament were hidden under a thick layer of brown wax. Just as the Victorians reacted against the neoclassicism of the eighteenth century, so modern taste reacted against the decorative use of colour and ornament of the Victorians. Many sculptures in Tate’s collection have been treated in the past and in some cases this has altered not only the appearance but also, as a direct consequence, the historical perception of these artworks. These treatments sometimes reveal more about the tastes of the restorers and their contemporaries than the artist’s original intent. Awareness of this has made present conservators much more cautious about changing the appearance of a work unless there is very good evidence that this was how the artist intended the work to look.

Fig.1

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889

Bronze, coloured resin paste and semi-precious stones

902 x 216 x 432 mm

Tate N01753

Fig.2

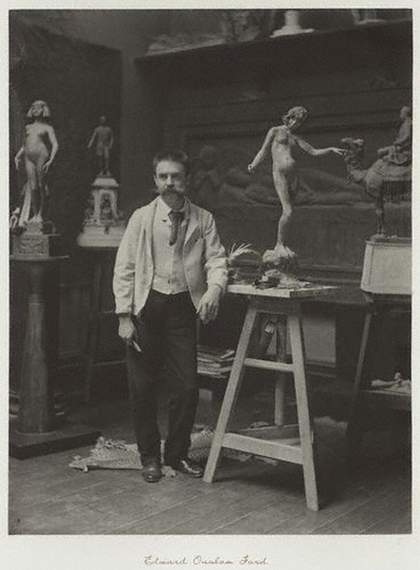

Ralph Robinson

Edward Onslow Ford in his Studio 1892

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Edward Onslow Ford’s The Singer, completed by 1889 and bought by Sir Henry Tate in 1894 for the Tate Gallery’s collection, depicts a girl harpist on a base decorated with Egyptian motifs (fig.1). The sculpture is a fascinating document about the Victorian perception of other cultures subsumed under the notion of ‘orientalism’ and reflects the sculptor’s interest in experimenting with different techniques. Ford, a British sculptor who has received only limited attention from art historians, was a close friend of Sir Alfred Gilbert (1854–1934). Gilbert and Ford occupied neighbouring studios in the mid-1880s and collaborated in reviving lost wax casting (fig.2).1 As a young man Ford had trained as a painter in Munich and therefore probably had a good knowledge of pigments and the use of colour. Ford was also in Germany at a time when debates were raging about the use of colour in sculpture sparked by the discovery of pigment on recently excavated works from antiquity.

A Tate Gallery catalogue entry of 1898 describes The Singer: ‘A girl with an Egyptian head-dress stands on a small bronze base with Egyptian figures at the corners; with her right hand she strikes a chord on a tall enamelled Egyptian harp that stands at her right side. The brass base is decorated with Egyptian symbols in coloured enamels. The whole is supported on a bronze lotus-shaped pedestal inserted in a black marble base.’2 However, in 1994, when the sculpture came to the conservation studio, it was uniformly dark brown, suggesting a darkly patinated bronze (fig.3). Thus early descriptions of the piece, and even a fairly brief examination, indicated that there was more to be discovered about the surface than its superficial appearance suggested.

Fig.3

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer exhibited 1889 (before conservation treatment)

Fig.4

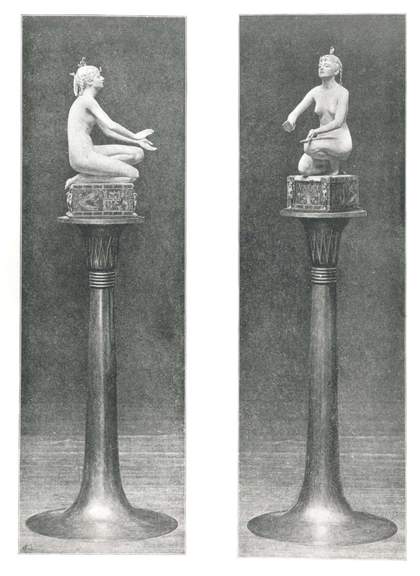

Period photographs showing original pedestal for Applause 1893

It is clear that Ford had not intended his sculpture to be a dark brown and our first task, before treatment could be carried out, was to determine what the sculpture had originally looked like. Unfortunately, there is no archive for Ford, or any existing notebooks or correspondence which might have described how he made this sculpture. There are, however, two clues as to how The Singer had looked when it left Ford’s studio. There is a ‘sister piece’ to The Singer called Applause made slightly later, in 1893. Tantalising images in black and white (fig.4) show significant stylistic similarities especially in relation to the decorative motifs of the base.3 We managed to trace the sculpture through the wills of the family which had originally bought the sculpture from the artist.4 Luckily, the sculpture was found in a private collection. Many Victorian sculptures are cherished family objects unknown to art historians and it was a delight to be able to see this sculpture so well looked after. However, although stylistically very similar, the techniques employed to create Applause proved to be very different from those used in The Singer.5

Fig.5

Wolfram Onslow Ford

My Father Black and white photograph of the oil painting (now untraceable), published in The Studio 1902

The second clue was discovered in a black and white photograph of an oil painting by the sculptor’s son, Wolfram Ford, entitled My Father before 1894, which showed The Singer in the background (fig.5).6 This offered the hope of a rare colour representation of the sculpture, but sadly the painting remains untraced, perhaps destroyed. The best clues to the original appearance of the colourful enamel decoration, therefore, remained those within the early catalogue description.

Such examples illustrate how difficult it can be to find documentation about the appearance of an even relatively recent work, a problem compounded if one is interested in something as elusive as colour. We therefore had to rely on microscopic examination and chemical analysis of the surface to reveal information about the original materials and techniques used.

The casting technique appears to have been lost wax. The harp was cast in two pieces and soldered together. A minute sample of metal taken from the harp identified it as bronze rather than brass as earlier described. The three elements are attached by bolts; the harp and base and bolted to the figure. When the harp was detached, cells of bright blue and pale red were seen in a protected area. It looked like the cloisonné enamel and, initially, was thought to be a badly fired, but conventional, glass enamel. However, when it was analysed, much to our surprise, it was not a true glass enamel at all but a mixture of chalk (calcium carbonate) and pigment bound in an oxidised natural resin.7

The base comprised four panels and the cloisonné-type cells were made from copper or brass strips and soldered to the back plate. With traditional cloisonné the thin strips of metal are soldered to the surface forming the outline of the pattern and creating cells or cloisons into which the powdered glass enamel is laid and fused. In this case, rather than using powdered glass, resin was pushed or poured into the cells, covering the screws and completing the decorative scheme. A blue resin mix filled the whole panel, and the red resin was then added over it in selected areas. Here and there, the red appears to have spilled out of the intended areas, suggesting that the resin paste was not easy to control. The surface was then polished to an even level.

Information on historical precedents for the use of resinous material in making what is essentially a fake enamel remains scant. The Victoria and Albert Museum has several medieval plaques with coloured inlay resembling that found on The Singer. Also, some contracts for medieval brasses specified resin-based inlays, but because this material is less durable than true enamel, few have survived intact.8

Analysis helped identify the constituents of the resin inlay as well as the coatings over it. Edges of the ‘enamel’ that had been chipped or broken also provided useful information since they revealed the inlay beyond the surface structure. The red and blue colours were not simply paint layers which had been applied to the surface but rather pigments that had been mixed into the resin. The pigments were identified as Prussian blue and Mars red. Identifying the pigments was important in this study, as different pigments age in different ways, and may be chemically reactive, limiting the possible materials that might be used in cleaning.

When the conservation record began in 1978, the coating on the sculpture was said to have darkened to a black colour. What had happened to the colourful ‘enamel’ underneath? In fact, there had been no darkening of the coating. Rather, the surface had been coated in a dark brown wax, most probably beeswax; a treatment used on many sculptures from this period. It is unclear whether this treatment was meant to cover a damaged or deteriorated surface or was simply a standard ‘maintenance’ treatment. Removing the wax might leave the sculpture looking worse so cleaning tests were needed. When the wax was removed with a solvent, rather than finding the bright blue and red colours expected, a yellow brown crystalline deposit remained on the surface. This layer was found to be linseed oil, which darkens as it ages. Had the artist applied the linseed oil after the sculpture was made as a type of varnish, which would have enhanced the blues and reds, or had this been applied later by a restorer?

Microscopy provided a possible answer as it revealed remnants of the discoloured oil layer over areas where the coloured enamel had been lost or damaged. That the oil went over these damaged areas suggests that this layer was a later addition, perhaps added to saturate and brighten the colours. However, it is also possible that the sculpture might have originally been coated with an oil and was re-coated when this began to degrade. It is impossible to say exactly when the linseed oil was applied but, in order to reveal the colour of the sculpture, a method was needed to remove this deteriorated and darkened oil layer. This presented a complex cleaning problem.

As the coloured resin was soluble in many of the substances that would dissolve the discoloured oil, it was difficult to remove the oil without damaging the resin. Several different cleaning options were considered; the one most extensively investigated was the use of an enzyme to break down the oil. The lipase enzyme has been used intermittently in the conservation of paintings and objects but is still relatively unexplored. Such enzymes occur naturally in the small intestine in humans as well as in other animals and were chosen because they can break down the oil into fatty acids. This is, of course, the same reason why they work to remove fatty stains from our clothes when they are added to biological washing powders.

In this application, unfortunately, the enzyme was not effective in removing the oil. The surface of most art objects is chemically complex and enzymes are temperamental. The age of the oil and the other materials such as remnants of wax, metal ions from the surrounding brass and oxides from the pigments may have contaminated the oil, preventing the action of the enzymes. It was therefore decided that the safest and most effective way to remove the oil layer was a combination of mechanical and chemical cleaning. Mechanical cleaning was carried out using the fine point of a surgical scalpel under a microscope. Not only was this method slow but using a scalpel was difficult in some areas because the resin was pitted and irregular. Further tests were therefore carried out using an alkaline cleaner. Since the alkaline cleaner could chemically react with the Prussian blue pigment in the blue ‘enamel’ cells and change the colour to a brown/orange, extensive tests were first done. An effective mixture was safely formulated and used to remove the oil layer. Once cleaned the detail of the vibrant blues and reds in the base and harp were revealed and the Egyptian decorative surface could again be seen.

Fig.6 The Singer exhibited 1889 (detail of front of plinth mid-restoration)

The bronze figure was the final part of the sculpture to be cleaned. Initially, we were not intending to remove the dark wax from the bronze as it was not clear how much of the original patina would be found. Decisions about removing previous treatments always involve weighing up the risks and benefits: some restorations can be historically interesting in their own right, while any treatment will put the object at some risk. In this case, however, given the amount of colour revealed on the base and the harp, the dark wax remaining on the bronze disturbed the visual coherence of the sculpture and obscured the detail of the figure. The wax was removed using white spirit solvent revealing a green and brown patina, but the underlying oil was left as it was relatively undegraded and did not distract from the appearance of the sculpture. However, a layer of neutral coloured wax applied to the surface helped unify the sculpture. Although there were areas of wear in the patina, the greens and browns of the original complemented the delicate surface of the harp and base (fig.6).

Since the decorative surface has been revealed there has been renewed interest in this piece, including its recent display in an exhibition about colour in sculpture.9 The Singer can once more be understood in a context of highly decorative nineteenth century sculpture, which is beginning to receive greater scholarly attention and public appreciation.