Fig.1

Edward Onslow Ford

Folly 1886

Bronze

887 x 415 x 330 mm

Tate N01758

1884 represented an annus mirabilis for sculpture in Britain, in particular for full-sized, bronze statues of youthful male nudes, represented at the Royal Academy that year by Ford’s Linus, Alfred Gilbert’s Icarus, Hamo Thornycroft’s Mower, and Auguste Rodin’s The Age of Bronze. In such august company, Linus did not particularly shine, and perhaps as a result of its comparatively poor showing, Ford subsequently turned his attention to a range of adolescent female nude statuettes that came to characterise much of his later practice.

This interest in the adolescent female body was not exclusive to Ford. In 1886 Ford’s Folly (fig.1) was joined at the Royal Academy by Frederic Leighton’s Needless Alarms, and could have been compared with Gilbert’s An Offering to Hymen simultaneously on show at the Grosvenor Gallery a short walk away. Indeed, the ‘concept of adolescence and the passing of childhood’ has recently been presented as a ‘potent source of inspiration’ for the so-called New Sculptors of Ford’s generation.1 However, as the writer Walter Armstrong suggested as early as 1890, Ford’s work represented, among his contemporaries, the most sustained exploration of the theme of female adolescence, while Ford himself possessed a peculiar predilection for models who would grow, during the sittings, from children into women, so that the resultant work would unite ‘some of the characteristics of either age’.2

Late nineteenth-century sculptors were not the only late Victorians interested in the subject of adolescence, and in many ways Ford’s interest in adolescent girls was a hallmark of late-Victorian modernity.3 That was because the adolescent female body was the subject of much contemporary debate following the Labouchere Amendment to the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885, which had raised the age of consent from twelve to sixteen in order to provide adolescents with greater protection from sexual predation. The Labouchere Amendment had been hurried through Parliament in response to the publication, in The Pall Mall Gazette in July 1885, of W.T. Stead’s campaigning series of articles titled ‘The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon’, which inter alia revealed the remarkable ease with which Stead had been able to purchase sex with Eliza Armstrong, the thirteen-year-old daughter of a chimneysweep, as evidence of the scandalous sex trade in British cities.4

The ‘thin but ethereally beautiful adolescent’ female figures in The Singer and Applause, to borrow a phrase from the art historian Mark Stocker, could be said to represent the kind of young women whom the Labouchere Amendment sought to protect.5 From 1885 Ford’s work shows a preoccupation with adolescent female models, but how the sculptor’s contemporaries responded to this, and how these bodies should be interpreted now, are questions that are difficult to answer.

Fig.2

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer 1893

Bronze, silver, enamel and semi-precious stones

902 x 216 x 432 mm

Tate N01753

This is in part because it is not possible to know for sure the age of the model used in The Singer (fig.2). The front of the figure, for example, seems to represent a girl of a more advanced age in comparison to the view of her body from the back. In fact, it is difficult to reconcile the ages of several of the body parts: the thighs and torso are both more elongated than would be expected for a girl with such a childlike face. While the upper torso reveals a pair of small breasts, the lower torso is arched backwards seductively. The overall effect suggests that the various parts of the figure’s body are growing at different rates. The pose in which Ford modelled the girl exaggerates the tension between her probable innocence and possible eroticism. The figure seems to step confidently forward with her right leg and raised right foot, but to be holding back on her left side. From the right-hand side of the figure, the girl’s right shoulder leans towards the viewer, though she pulls her bottom backwards and away. The girl also seems to pull her abdomen in and up to the top left, but looks down to the bottom right, while the harp strings that she plays articulate a similar tension, as they are held back, waiting to spring forward. The dynamics of extension and contraction visible in the figure’s muscles are metaphorically mirrored by the screws on the top of the harp, which can be tightened or slackened like tendons, while the different textures of the harp strings, as well as the girl’s hair and skin, invite the beholder’s touch (fig.3).

Fig.3

Edward Onslow Ford

Detail of harp screws in The Singer

Fig.4

Edward Onslow Ford

The Singer (detail)

If The Singer could be said to be a crude pun on the possibilities of ‘plucking’, given the position of the girl’s hands at crotch height, the statuette does not unequivocally endorse erotic readings, and could even be interpreted as a warning against voyeurism. Viewers who make eye contact with the girl, for example, may feel awkward and self-conscious, unsure of the extent to which their gaze might be warranted or welcomed. Even from the side views, where the figure cannot catch the eyes of the viewer, the predatory, diamond-encrusted gaze of the snakes on the pedestal, as well as the ibis in the headdress and on the harp, disarm voyeuristic looking by returning the voracious gaze, emphasised by the pupil-like shape of the turquoise bosses on the headdress (fig.4).6 It is worth drawing attention to these predatory gazes because, in ‘The Maiden Tribute’ articles Stead expressly described the abducted young girls to be raped and made into prostitutes as ‘prey’, and characterised the lucky ones who escaped as ‘bird[s who] had flown’.7 In addition, from the right-hand side, the girl’s harp bars access to her body; to pass through it would lead to being arrested in its web-like strings. There is also an arachnid-like quality about the combination of lightness, strength and agility in the figure’s tense right hand, recalling a spider traversing its web. There may again be a visual allusion to ‘The Maiden Tribute’ articles which had suggested that individuals might get ‘caught in the coils’ of the London cultures of prostitution, with its ‘secret’, ‘lair-like recesses’.8

Given the proximity of the girl’s hand to her genitalia, The Singer raises the contemporary spectres of the sexual predation of adolescent girls as much as it suggests predation on them.9 Whether the girl’s eroticism is part of her self-conscious performance, or originates in the eyes of voyeuristic beholders remains an open-ended question. Are the girl’s cheeks flushed because she is aroused, or because she is ashamed at being naked in public? Do the girl’s crossed upper thighs suggest an implicitly adult pleasure, or do they resemble a child’s need for the toilet? Does the serpentine curve of the girl’s silhouette, seen from the side, invite identification with Eve, especially since it is echoed by a similarly motile snake on the base (which itself carries a harp-like instrument in its mouth), and by the rising snake-scaled form of the girl’s instrument, which also seems to have been charmed into verticality? And if so, does The Singer self-consciously allude to that staple of Orientalist painting, Jean-Léon Gérôme’s The Snake Charmer c.1870 (Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown), which similarly juxtaposes a rearing snake with a nude, sexually vulnerable child’s body?10 Alternatively, do the Egyptian themes of The Singer allude to that moment in ‘The Maiden Tribute’ articles where a soon-to-be-convicted madame, Mrs Jefferies, complains mournfully to Stead that business had been ‘very bad’ since ‘the Guards went to Egypt’?11

Fig.5

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail)

Fig.6

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause (right-side view) 1893

The figure in Applause has three snakes on her headdress: one on the top of her head and two at her forehead, each weaving among the precious stones of her crown, as a profile view reveals (fig.5). From these side views, the girl’s braids of hair echo the serpentine curves of the snakes, descending from the top of her head to the base of her neck, where they coil, overlap, and rear up, like the ribbons immediately behind them. There is also a snake-like quality about the way in which the profile silhouette of the girl’s hands resembles the rearing open mouth of an attacking snake (fig.6), akin, for example, to the python in Frederic Leighton’s An Athlete Wrestling with a Python 1877 (fig.7).

Fig.7

Frederic, Lord Leighton

An Athlete Wrestling with a Python 1877

Tate N01754

Given the sudden and profound rethinking of adolescent sexuality necessitated in the aftermath of the Labouchere Amendment, Ford and his contemporaries were divided over the nature and extent of his adolescent models’ innocence, while reviewers were unsure what, if anything, Ford’s own preoccupation with such youthful bodies revealed about the artist. Representing one point of view, art critic Edmund Gosse identified the ‘extreme finish of the surface of the flesh’ in Ford’s work with the ‘apex of sanity and health’.12 Folly was also enough of a mainstream figure for the Royal Academy to purchase it under the Chantrey Bequest, and art critic M.H. Spielmann praised the ‘beauty’ of the statuette’s ‘tender, undeveloped forms’.13 Ford himself claimed that he had ‘no sympathy’ with Rodin’s ‘ungoverned and sensuous emotion’, thereby emphasising Ford’s own empathetic relation to his models.14 Representing an opposing perspective, however, was the female art critic Marion Hepworth Dixon, whose encounter with Ford’s work has provided the richest material for analysis in this context. While Dixon thought Ford’s bust of an adolescent girl, A Study 1886, contained the ‘very perfume and essence of the young girl’ in that the figure was ‘fair, rounded, peach-like and yet almost removed and aloof’ in her ‘virginity’,15 she felt it necessary, in 1892, to assert that Ford’s work revealed ‘something individual’, ‘special’ and ‘dual in his nature’, although maintained that the artist’s relation to his adolescent models did not merit reproach.16 Dixon claimed that Ford’s ‘fidelity’ to the truth of the model’s body was ‘loving’ and ‘unwavering’, more marital than exploitative. And while those who, like the playwright Oscar Wilde in 1895, fell foul of the Labouchere Amendment were sentenced to prison with hard labour, Dixon believed that Ford’s statuettes, on the contrary, were already full of ‘labour, hard and unremitting’.17

Writing again in 1898, Dixon was perhaps more willing to acknowledge the ‘daring realism’ of Folly’s ‘lower extremities’, but also sought to differentiate Ford’s ‘tender’ and ‘loving’ realism from John Singer Sargent’s ‘cold, accusing’ version, and Rodin’s ‘ruthless, remorseless fidelity’, and from what she characterised as the ‘pretty subterfuges and compromises’ of more conventional work. But perhaps with the Labouchere Amendment in mind, Dixon would acknowledge that Ford was a ‘man of his time’ and full of its ‘contradictions’, and characterised him as an artist whose realistic depictions of adolescent girls spoke ‘the whole truth and nothing but the truth’.18 In 1900 Dixon returned to these themes when she acknowledged that the sculptor’s work articulated ‘the modern mind’, and she praised Ford’s adolescent types in comparison with the ‘smug and tripping graces’ and ‘fine Olympian bluff’ of more conventional sculptors. Perhaps alluding more directly to The Singer, she also described Ford’s ‘muse’ as ‘shy and captivating rather than noisily self-assertive’, and as a figure who employed no ‘blast of trumpet or clarion’, but ‘rather a harp’. Dixon again described Ford’s ‘devotion to actualities’, as if it were a sort of religious calling, and characterised it as the ‘better sort of naturalism’. Dixon was also at her least phobic around these issues when she described how Ford’s adolescent girls were all figures by whom viewers might be lured into ‘primeval forests’ and to whom we might offer ‘milk, oil, and honey, even the sacrificial goat’.19

Similar anxieties and ambivalences can be detected in the notes about Applause written by the statuette’s first owner, Clinton Dent. For example, was Dent’s evaluation of the figure’s age a little far-fetched when he declared that Ford’s model for Applause was a ‘girl about 18’, whose ‘arms were slight’ and whose ‘hands consequently looked large’; a young woman, therefore, older than the newly agreed age of consent.20 The answer to this question is, perhaps, no, since Dent also praised, as ‘one of the chief attractions of the artist’, the ‘wonderful grace’ to be found in the ‘curving lines’ between the model’s ‘thighs and legs’, and the realism of the girl’s clavicles and the folds of skin at the back of her neck.21 In addition, Dent noted that it was ‘not easy to put a headdress on a naked figure and make it look decent’ but that Ford had achieved this. However, Dent felt that the figure’s bust was ‘less satisfactory’, ‘immature and weak in form’, but noted that this was common for ‘girls of eighteen, young for their years’ at least ‘in this country’.22

In addition, what sense can be made of the meaning, on the one hand, of depicting ancient Egyptas an adolescent girl, and on the other hand, depicting an adolescent girl in neo-Egyptian guise? Did Ford feel the need to displace his artistic investment in adolescent eroticism onto ancient Egypt, rather than late-Victorian culture? Was he seeking a historical alibi for his own ongoing personal, or professional investment in the bodies of adolescent girls? Alternatively, did Ford seek to suggest that ancient Egypt itself represented a ‘cultural adolescence’ that culminated in the maturity of Greco-Roman classicism? (This certainly became a standard characterisation of ancient Egyptian visual culture following the publication of J.J. Winckelmann’s highly influential History of Ancient Art in 1764.) Or did Ford purposefully evoke a sense of the ‘pre-mature’ in response to the mid-to-late Victorian interest in the primordial, exemplified by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood? (Frank Rinder argued in 1902 that Ford’s work partook of the ‘nature of the Pre-Raphaelite movement of an earlier day’.23 ) Perhaps by juxtaposing his adolescent girls with hieroglyphs and iconography derived from ancient funerary contexts, Ford was implying that adolescence was the death of childhood, or that Victorian culture was responsible for the death of acceptable early adolescent eroticism?24 While Ford may have included Egyptian mortuary motifs in The Singer and Applause to suggest the impending death of the culture of eroticised adolescence after 1885, his use of Egyptian motifs paradoxically testify to the longevity of that culture (after all, Ford’s own work showed no signs of abandoning the adolescent female body after 1893).

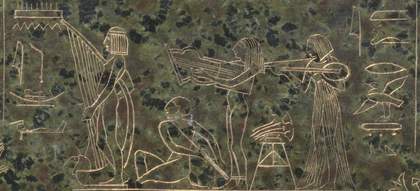

When Applause was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1893, it was accompanied in the catalogue by a quotation from the ancient Egyptian ‘Harpist’s Song’. Known from Middle Kingdom monuments (c.2040–1640 BC), later examples of the text, on which Ford’s copy was based, state that they are copies of an inscription in the tomb of King Intef in western Thebes opposite modern Luxor.25 The translation was an 1876 version by the man who commissioned the statuette, the mountaineer and art collector Clinton Dent, and it derived from the hieroglyphics on the statuette’s pedestal. The song, presented on Applause in hieroglyphs, suggested that viewers surround themselves with ‘song and music’, put behind them ‘all evil cares’, and ‘think … only [of] happiness’, since the ‘day of the departure’ to the ‘land of loving silence’ would come soon enough. Or, as an anonymous contributor to The Country Gentleman put it, ‘Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die’.26 And, as a variety of ancient papyrus manuscripts, wall paintings, relief sculptures and tomb carvings testify, benet or harps played a complex, central and long-standing role in Egyptian sacred and secular culture. This section will now consider both the religious and sexual contexts in which both the main figure in The Singer, and the closely-related hieroglyphic image of the harpist who leads the upper register of figures on the side panels of Applause, should be placed.

Fig.8

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail of plinth)

While there is no unequivocal evidence to demonstrate the extent of Ford’s engagement with the Egyptological evidence potentially available to him in museums, galleries and private collections across Europe, various aspects of the neo-Egyptian statuettes’ ambiguous iconography suggest that he was aware of both the sacred and secular, and the textual and performative significance of his subjects. For example, Ford suggests the sacred contexts of harp music by the way in which he includes, on the side panels of Applause, the two rows of musicians, including The Singer leading the upper register, in the act of worshipping larger divine figures, including a winged figure (fig.8). In addition, the far-reaching gaze of the main figure in The Singer suggests that her thoughts are upon the divine, rather than the secular world. The pointedly open mouth and expanded chest of this figure, along with the elegant modelling of her curved spine, wrists and fingers, not to mention her royal headdress and lavishly decorated instrument, all advance the interpretation that she represents one of the ritual singers and dancers of Amun, one of the most important of the Theban gods.

If the readings outlined so far allude to the sacred understanding of the ‘Harpist’s Song’, the two statuettes, like the song itself, invite secular and sexual readings. In accordance with the song’s permission to surrender to earthly pleasures, the two naked adolescent girls come powerfully into their own as erotic objects. Given her nudity and the inelegant character of her knees and feet, one can easily imagine the main figure in The Singer to represent a naked servant or slave girl, or an artistically trained woman from the royal harem selected to perform at banquets. In addition, while harps were traditionally played to accompany solo singers, as in the case of The Singer, the pair of harpists within the two tiers of walking and standing musicians on the side panels of Applause remind us that harp music also played a part in highly embodied, group activities such as banquet performances and ritual processions, accompanied by clapping and chanting crowds, where they were often joined by naked adolescent and child dancers.

Fig.9

Panel of the Nebamuns Tomb (BM 37981)

British Museum

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.10

Edward Onslow Ford

Applause 1893 (detail of plinth)

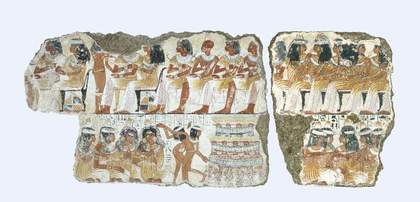

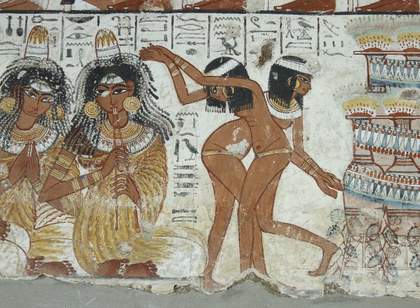

The former of these activities represents exactly the erotically-charged scene depicted in one of the most important primary sources for The Singer and Applause: the eleven painted wall fragments from the eighteenth-dynasty hill-side tomb at Dra Abu-el-Naga, belonging to Nebamun, the Theban accountant in charge of grain at the Temple of Amun. These paintings were excavated in, or shortly before 1820 by the archaeologist and collector Giovanni d’Athanasi, and are now on display at the British Museum.27 Of particular relevance here are the two registers of polychromed banquet scenes, depicting a mixed-gender audience seated together, attended to by naked servant girls, and entertained by four seated musicians and two dancers (fig.9). These fragmentary scenes need to be highlighted for two reasons: firstly, because the seated tibia player has a loose family resemblance to the three wind players (two seated and one standing) in the side relief of Applause (fig.10); and secondly, though most representations of Egyptian antiquity feature women in long, tight white dresses, the dancers here, like Ford’s two neo-Egyptian figures, are more or less naked, wearing only girdles, ear-rings, bracelets and armlets. Indeed, the nudity, eroticism and sexual availability of the dancing and serving girls – some of whom, like Ford’s adolescent girls, are depicted full-face – is rendered explicit in the surviving fragments by the juxtaposition of naked flesh with various items of jewellery, and by the visible pubis of one of the serving girls in contrast to the obliterated pubis of another (which a seated male diner immediately to the right seems to be reaching for, only to be restrained by his female dining companion, although the iconography in fact depicts the man with his arm on his lap, while his dining companion holds his arm affectionately; fig.11).28 In addition, two of the depicted dancing girls, both of whom pointedly make eye contact with the viewer, are clapping, one with her hands above her head, and the other, like Applause, with her hands at thigh level in left profile (fig.12).

Fig.11

Detail of panel of the Nebamun's Tomb

British Museum

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.12

Detail of panel of the Nebamun's Tomb

British Museum

Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum

The archaeological evidence that can be used to support interpretations regarding the nature of Ford’s adolescent nudes, then, fails to provide unambiguous conclusions. On the one hand, the statuettes can be seen as quasi-sacral objects depicting religious figures, while on the other, they can be enjoyed in light of their erotic appeal. Given the raising of the age of consent brought about by the Labouchere Amendment in 1885, it is unclear whether The Singer and Applause testify to Ford’s nostalgic admiration for ancient Egyptian culture, or emphasise its cultural, geographical and historical distance from his London studio.