Although this was his first visit to Vattetot-sur-Mer, Rothenstein’s reputation as an artist had long been connected to France, for it was here that he had received his primary training. Leaving Bradford Grammar School to join the Slade School of Art in London in 1888, the young artist lasted only a year in London before making the move to Paris. Studying initially at the Académie Julian (1889–93), Rothenstein gradually integrated himself within networks of contemporary French artists including Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, Louis Anquetin, Jean-Louis Forain and Paul-Albert Besnard.1 The work of graphic artists including Théophile Steinlen and Charles Leandré also proved important, as the young artist sought to find a subject matter and style that suited him.2

A Parisian education was not an especially surprising move for an English artist in the closing decades of the nineteenth century.3 The range of contacts Rothenstein made, however, and the wide interest his work provoked, was rare. In 1891, still only nineteen years old, he shared an exhibition with Charles Conder at Père Thomas’s gallery on the Boulevard Malesherbes, receiving favourable press attention and encouragement from Edgar Degas and Camille Pissarro.4

William Rothenstein

Parting at Morning 1891

Chalk, pastel and bronze paint on paper

1295 x 508 mm

Tate

Although Rothenstein claimed to have destroyed much of the work he made in Paris, some major pieces still exist. These include two bold figure studies, an early landscape, a small group of drawings and pastels and a large sketchbook of 1889–93, now in the Tate archives.5 Of the two figure studies, Parting at Morning 1891 (Tate T07283; fig.1) is perhaps the most impressive.6 Standing over a metre high, it depicts an emaciated female figure (‘cadaverous’ was the word Rothenstein used to describe the model) against a plain bronze background.7 The outline of the figure is strong, recalling the work of the French artist Puvis de Chavannes: a heroic figure among young British artists during this period.8 The choice of subject – ostensibly inspired by Robert Browning’s 1845 poem of the same name – is a brave one, confirming the sympathy Rothenstein claimed to feel for realist painting.9 The use of bronze paint nonetheless suggests the competing claims of symbolism and the decorative arts.

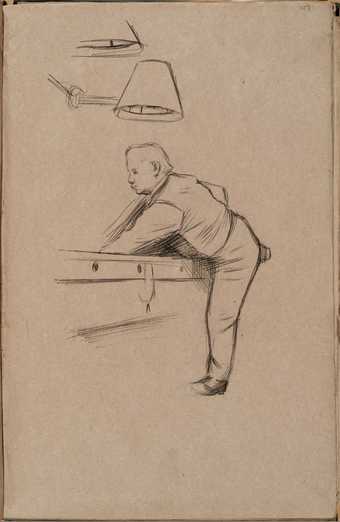

Rothenstein’s Parisian sketchbook runs to well over a hundred pages and contains work made both in Paris and on periodic returns home to Yorkshire. It shows the full range of Rothenstein’s interests during this period, including copies after Diego Velázquez and Japanese prints (figs.2 and 3), contemporary street scenes (fig.4) and hazy landscapes, vibrant self-portraits (fig.5) and meditative portraits of unnamed figures (fig.6). A series of portraits of men and women playing pool (fig.7) suggest an artist eager to experiment with unexpected subjects and challenging compositions. All of these sketches show that Rothenstein was alive to a large and varied group of interests, many of which – such as Spanish painting and Japanese prints – would remain important to him for many years. A keen admirer of Velázquez’s work, Rothenstein would also go on to write the first English monograph on Goya and to collect work by Hokusai.10

Fig.2

William Rothenstein

Copy after Velázquez c.1890

Chalk and ink on paper

370 x 238 mm

Tate Archive TGA 806/5/2

Photography © Tate 2016

Fig.3

William Rothenstein

Copy after Japanese Prints c.1890

Ink on paper

370 x 238 mm

Tate Archive TGA 806/5/2

Photography © Tate 2016

Fig.4

William Rothenstein

Parisian Street Scene c.1890

Graphite and chalk on paper

238 x 370 mm

Tate Archive TGA 806/5/2

Photography © Tate 2016

Fig.5

William Rothenstein

Self-Portrait c.1890

Graphite and coloured chalk on paper

370 x 238 mm

Tate Archive TGA 806/5/2

Photography © Tate 2016

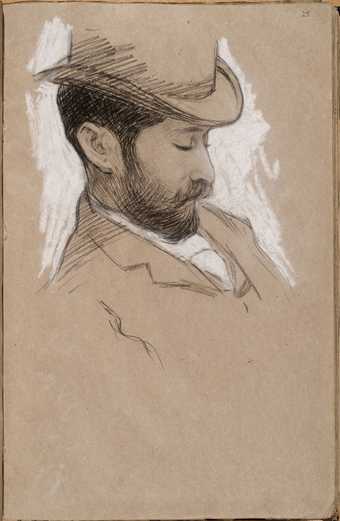

Fig.6

William Rothenstein

Portrait of a Man c.1890

Graphite and chalk on paper

370 x 238 mm

Tate Archive TGA 806/5/2

Photography © Tate 2016

Fig.7

William Rothenstein

Man Playing Pool c.1890

Graphite on paper

370 x 238 mm

Tate Archive TGA 806/5/2

Photography © Tate 2016

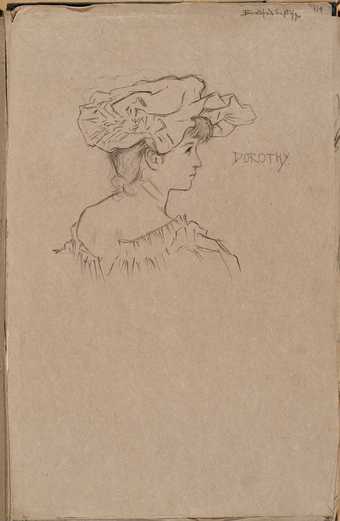

Fig.8

William Rothenstein

Dorothy c.1890

Graphite on paper

238 x 370 mm

Tate Archive TGA 806/5/2

Photography © Tate 2016

Certain themes reoccur throughout the sketchbook, not least images of young women in fashionable outfits, often seen from behind (fig.8), or posed in interiors (fig.9), the latter recalling not only Whistler’s Symphony in White, No.2: The Little White Girl (Tate N03418) but many of Rothenstein’s later paintings, such as Alice by the Fireside, an unfinished portrait of his wife (fig.10), probably painted in the early 1900s. Just as The Doll’s House uses the staircase as a prop around which to stage the human figure, many of Rothenstein’s paintings including Alice by the Fireside utilise the fireplace as a dramatic device.11

Fig.9

William Rothenstein

Female Figure in Interior c.1890

Graphite on paper

370 x 238 mm

Tate Archive TGA 806/5/2

Photography © Tate 2016

Fig.10

William Rothenstein

Alice by the Fireside c.1905

Manchester City Galleries, Manchester

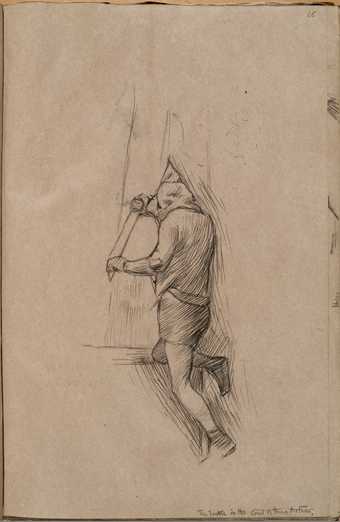

Another reoccurring theme in the sketchbook – with implications for The Doll’s House – is that of the literary subject. At least two drawings have literary connections. One sketch of a man in medieval costume brandishing a sword is given the title The Yankee at the Court of King Arthur, referring to Mark Twain’s recently released novel (published 1889) (fig.11).12 The title raises immediate questions: is the drawing a copy of an illustration, an original illustration, or does it have a more tangential relationship with the text? The latter option seems the most likely, anticipating the confusion surrounding the relationship between The Doll’s House and Henrik Ibsen’s play of an almost identical name.13 Meanwhile, another drawing showing a couple of young tennis players is titled, wryly, A Lawn – Tennysonian Idyll (fig.12). Although it would be difficult to describe this study as psychologically tense, it nonetheless represents an early exploration of a relationship between a male and female figure, posed in close proximity, but evidently struggling to communicate. The tennis net, it could be argued, functions in a similar way to the balusters in The Doll’s House, or the striped sofa in Porphyria 1894 (also known as Porphyria’s Lover; private collection): a physical barrier that suggests emotional distance. For now, however, the idea seems to have gone no further than a rough sketch.

Fig.11

William Rothenstein

Yankee at the Court of King Arthur c.1890

Graphite on paper

370 x 238 mm

Tate Archive TGA 806/5/2

Photography © Tate 2016

Fig.12

William Rothenstein

A Lawn – Tennysonian Idyll c.1890

Graphite on paper

370 x 238 mm

Tate Archive TGA 806/5/2

Photography © Tate 2016

Despite Rothenstein’s success in Paris, he returned to England in 1893, following a commission to make a series of lithographic portraits of famous Oxford figures, later published as Oxford Characters (1896).14 Upon his return, Rothenstein was regarded as something of an ambassador for French culture. Establishing himself in Francophile circles in Chelsea and exhibiting with the New English Art Club, many of whose members had also studied in Paris, Rothenstein made good use of his connections, encouraging the poet Paul Verlaine to give a lecture in London in November 1893, reviewing Paris exhibitions for the Studio magazine and producing portraits of such figures as Edmund de Goncourt, Emile Zola and Auguste Rodin.15 A key figure in the promotion of Rodin’s work in England, Rothenstein was subsequently instrumental in the organisation of the 1900 exhibition of Rodin’s work at Carfax and Co.

In April 1894 Rothenstein exhibited two paintings at the New English Art Club with French titles: Le Homme Qui Sort, a portrait of his friend Charles Conder (Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo), and Jeune Paysanne Assise, a nude study, now at the Musée D’Orsay in Paris. The use of French titles in a London exhibition made it quite clear where the artist’s influences lay and it annoyed at least one critic. Writing for the Speaker, George Moore (whose own Parisian education had been described in his 1888 memoir, The Confessions of a Young Man) saw evidence of ‘natural talent and future fruition of artistic taste and power’ in Rothenstein’s work, but felt that the titles were ‘a little comic’.16 The image of Rothenstein perpetuated by the press in the 1890s is one, duly, of the young cosmopolitan, a parody of which would later be published by his friend Max Beerbohm:

In the summer of ’93 a bolt from the blue flashed down on Oxford … Its name? Will Rothenstein … He wore spectacles that flashed more than any other pair ever seen. He was a wit. He was brimful of ideas. He knew Whistler. He knew Edmund de Goncourt. He knew everyone in Paris … He was Paris in Oxford.17

In this passage, Rothenstein’s Bradford roots are neatly overlooked: he might as well have been a native Frenchmen, Beerbohm argues, underlining the importance (for better or worse) of Rothenstein’s Parisian education in the early years of his career.

Although Rothenstein’s relationship with his Parisian past would start to shift at the turn of the century as he attempted to disassociate himself from the passing decade and establish himself as a leading English artist, he would continue to visit France regularly over the course of his career, with a particular fondness for the landscapes of Burgundy and Normandy.18 His work continued to be informed by his close knowledge of French art, and there can be no doubting that he formed a vital link between the practices of Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec and British art in the early twentieth century. The fact that The Doll’s House, perhaps his most famous painting, was created in France and owed much of its success to its exhibition in the 1900 Paris Exposition Universalle, could therefore be considered wholly appropriate.