Among the many conversations shared by William Rothenstein, William Orpen, Augustus John, Charles Conder and Albert Rutherston during their summer together at Vattetot-sur-Mer in France in 1899, the relative merits of the old masters must have been a common theme. Far from dry and distant figures of the past, artists such as Diego Velázquez, Titian and Rembrandt van Rijn were, at the turn of the century, regarded as highly relevant touchstones for young artists. There was about them an air of excitement and discovery, fuelled by major publications, exhibitions and the discovery of new works. The foundation of art magazines such as the Studio and the Burlington Magazine, allied to a rapidly expanding art market and widespread insecurity over the direction of contemporary art, created an environment in which the artist and connoisseur were closely aligned – as Rothenstein’s early career bears out.1

Fig.1

Title page to William Rothenstein’s Goya (1900)

Published by At the Sign of the Unicorn, London, as part of the series The Artist’s Library edited by Laurence Binyon

Rothenstein did not like to think of himself as a scholar and would claim in the memoirs he wrote in the early 1930s that ‘I was never a real student of the arts, and preferred pottering about the streets in my spare time looking for bargains, to studying seriously in overcrowded museums’.2 In 1899, however, his fellow artists may have been forgiven for thinking otherwise. He was, after all, in the final stages of producing the first ever English monograph on the Spanish artist Francisco Goya (1746–1828; fig.1) which would be published the following year as part of Laurence Binyon’s series The Artist’s Library: one of many beneficiaries of the significant boom in arts publishing in the 1890s.3 Rothenstein’s book was an expansion of two essays he had written on Goya for the Saturday Review in 1896 following a trip to Spain with Robert Cunninghame-Graham the previous year.4 Although the books in Binyon’s series were short and aimed at a wide audience, there is no doubting that Rothenstein took his role seriously. His interest in art history was not that of the amateur: he read widely, studied material first-hand, and moved in circles in which a firm grasp of the old masters was almost expected.

Rothenstein’s interest in art history had begun at the Slade School of Art in London, under the tutelage of the French artist Alphonse Legros. Rothenstein described Legros as ‘a disciple of Mantegna, Raphael and Rembrandt, of Ingres and Delacroix, of Poussin and Claude’, who actively encouraged his students to copy works from the National Gallery and the Prints and Drawings Room at the British Museum.5 Keen to follow this advice, the young Rothenstein ‘filled more than one book with drawings after Michael Angelo, Raphael, Durer, Leonardo, Holbein, Signorelli and others’.6 He also copied Rembrandt’s etchings and the ‘head of an old man with a turban’ at the National Gallery in London.7

It was also at the Slade that Rothenstein started collecting works of art, just before prices began to rise precipitously. As he noted: ‘In the print shops [in London c.1890] one might find precious studies by old masters among the heaps of miscellaneous drawings in portfolios; drawings by Blake, Gainsborough and Rowlandson were by no means uncommon and could be purchased for a few shillings.’8 Rothenstein would go on to own work by Goya, Rembrandt, Hokusai and Thomas Gainsborough, among others, a collection that would impress young artists such as Augustus John, not simply because of its quality, but because it revealed Rothenstein’s skill in buying such well-regarded work for so little.9

Fig.2

Rembrandt van Rijn

The Slaughtered Ox 1655

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Fig.3

Rembrandt van Rijn

Philosopher in Meditation (Old Man in an Interior with Winding Staircase) 1632

Musée du Louvre, Paris

That which he started in London, he clearly continued in Paris. The presence of a copy after Velázquez’s Pablo de Valladolid 1636–7 in the artist’s Paris sketchbook – taken, most likely, from a reproduction, as the picture was in Madrid – is typical of the period.10 Velázquez’s reputation, bolstered by Édouard Manet and James McNeill Whistler, was reaching new heights which would come to something of a climax in R.A.M. Stevenson’s influential study The Art of Velasquez (1895), which made a distinct case for the artist’s modernity. Other works that made a great impression on Rothenstein in Paris were Fra Angelico’s The Coronation of the Virgin 1430–2 (Musée du Louvre, Paris) and two works by Rembrandt: The Slaughtered Ox 1655 (fig.2) and The Good Samaritan c.1650 (now attributed to a ‘follower of Rembrandt’; Musée du Louvre, Paris).11 One wonders whether Rembrandt’s ox carcass lay behind his decision to paint the Vattetot painting The Butcher’s Shop under the Trees (Tate N05946), despite the relative smallness (and tameness) of the butchered meat in Rothenstein’s canvas. Not mentioned in his memoirs, but surely exerting a similarly powerful influence, was Rembrandt’s Philosopher in Meditation 1632 (fig.3), which must have also been in Rothenstein’s mind when he started painting The Doll’s House.

Later in life John would write that ‘the aspiring student who thinks he may best find himself by pursuing the Old Masters is in grave danger of losing sight of his guides as well as his goal. He must take his directions, as did his distinguished predecessors, from life itself’.12 It is very likely that John was thinking of his own training, if not that of many of his contemporaries who, like Rothenstein, were steeped in the culture of the old masters. Rothenstein would no doubt have agreed with John that it was important not to be overly influenced by any one artist: a fault he attributed to artists such as Charles Ricketts.13 Indeed, a review by D.S. MacColl, written in 1900, suggests that Rothenstein was perceived by many to have struggled to overcome his influences. ‘I see that the critics, when they have not described Mr. Rothenstein’s painting as a slavish imitation of the Old Masters … have dismissed it as “clever work in the latest manner of the Parisian studios”’, wrote MacColl.14 Despite this accusation – with which MacColl disagreed – it is clear that Rothenstein strongly encouraged John and others to pursue the old masters at the turn of the century.

Not only was Rothenstein actively involved in art criticism via the Goya project, but he was also busy setting up a small commercial gallery in London, Carfax and Co, which would show the work of contemporary artists including Orpen, John, Rutherston and Rothenstein alongside the old masters. The financial advisor and later director of the gallery, Arthur Clifton, was present at Vattetot, but its co-founder John Fothergill was not: he was in Italy, buying up ‘old master drawings’ while recovering from an illness.15 Small though it was, the Carfax was representative of the conspicuous expansion of the art market in London in the final few decades of the nineteenth century, mirroring the ever-burgeoning art press and the rise of celebrated connoisseurs such as Bernard Berenson and Herbert Horne.16 The third exhibition ever held at Carfax, in the summer of 1899, contained ‘drawings by Titian, Goya, Alfred Stevens, Hokusai, Gainsborough, also by Legros, Conder, Strang, Rothenstein, John and others’.17 This pairing of contemporary artists with deceased masters must have prompted comparisons between the two, inviting viewers to see both the modern in the old and the old in the modern. These artists were, in a sense, piggy-backing on the successful trade in old masters, not only by sharing their exhibition space, but also by adopting elements of their style.18 There can be no doubt, in retrospect, that all of the artists who featured in this early exhibition were heavily indebted to the old masters, often in imaginative ways (as opposed to slavish imitations). Their influences were wide-ranging, as works by William Strang, Charles Shannon, Charles Conder and Augustus John suggest (see, for instance, Strang’s The Temptation 1899, Tate T07518, and Shannon’s The Bath of Venus 1898–1904, Tate N05160).19 One figure, however, rose above them all. This was Rembrandt.20

In letters sent to his parents in 1898 Albert Rutherston wrote of how William was keen for him to copy from works at the National Gallery, as he had done previously.21 Albert duly obliged, returning with the obligatory copy of a Rembrandt head. Only months later Albert reported back from a whole exhibition of work by the Dutch master: ‘I went to the Rembrandt show which almost takes one’s breath away it is so marvellous. Of course I shall go again’.22 The show in question was the retrospective at the Royal Academy, which opened in January 1899 followed in March by an exhibition of works on paper at the British Museum. These two shows came in the wake of the major 1898 Rembrandt exhibition in Amsterdam, which attracted over forty-three thousand visitors during its two-month run, and has been described as the birth of the modern ‘block-buster’ exhibition.23 The impact of these three exhibitions and their associated publications was huge, ensuring that the subject of Rembrandt was an unavoidable one in artistic circles c.1900.

In a study of Rembrandt’s reputation Catherine Scallen refers to the 1890s as the ‘Rembrandt Decade’.24 The first of eight volumes of the first fully illustrated catalogue raisonné was published by Wilhelm von Bode and Cornelius Hofstede de Groot in 1897, while new works flooded into the market, achieving increasingly high prices. Although the arrival of American collectors was a key factor, signalling something of a power shift in the international art market, a significant number of works by Rembrandt were in British hands at this point, as British critics were keen to point out in their reviews of the Amsterdam exhibition. ‘It is satisfactory to British people to know that by far the finest pictures in private hands were contributed by collectors in England and Scotland’ noted one proud critic in the Art Journal in December 1898: a factor which explains why London was able to host two independently organised Rembrandt exhibitions the following year.25 London asserted its right to be seen as the centre of Rembrandt appreciation, treating the artist as if he had been one of their own.

The Royal Academy show represented not only the pinnacle of Rembrandt’s reputation, but highlighted the importance of the Academy as the home of the old masters. Indeed, the very phrase had come into popular usage on account of their tradition, instigated in 1870, of holding a winter exhibition dedicated to the work of ‘old’ and ‘deceased’ masters. Such shows helped turn the attention of critics away from contemporary art and allowed people to compare and contrast artists whose work had rarely been seen in large numbers before. According to the critic Walter Armstrong, ‘No man profited more by this revival than Rembrandt. The more he was seen the greater he became, until at last he attracted a little court of critics of his own, a school, as it were, in which each member’s chief title to respect is that he knows his Rembrandt.’26 Despite the Royal Academy’s central role in promoting Rembrandt he was, interestingly, seen by younger artists as a natural enemy of academies: a rebel figure.27

There is no question that William Rothenstein was caught up in this wave of enthusiasm. Writing to the critic and painter Roger Fry in 1909, he noted: ‘I believe at the time [c.1899] I was perhaps more under the influence of Rembrandt than of Goya – you remember there was a great exhibition of his work at Amsterdam a little time before’.28 In fact, Rothenstein’s fondness for Rembrandt is made very clear in his book Goya, where the Dutch artist merits several mentions, as if Rothenstein would much rather be writing about him instead. It is also made very clear in paintings of the period, The Doll’s House in particular. The red ground that Rothenstein used for this work may have been taken from Goya, but the predominantly brown tone and dramatic lighting is much more reminiscent of Rembrandt.29

Rothenstein’s appreciation of Rembrandt, however, goes much further than simple visual comparisons, whether it be the detection of chiaroscuro or the nod to the gloomy staircase in The Philosopher in Meditation. What attracted Rothenstein to Rembrandt, ultimately, were the ideals he perceived to lie behind his art, that which Rothenstein would refer to in Goya as Rembrandt’s ‘serene and serious outlook on life, that profound interpretation of nature and Christlike sympathy for men and women, which he shows in his compositions.’30

A claim frequently made by critics during this period was that Rembrandt was neither realist nor fantasist, but a purveyor of ‘reality’. The critic Frances Low described him in 1898 as:

at once the most poetic of painters and the real, so that he is not wholly governed by mysticism like our own Blake, and still less is he wholly naturalistic … He takes an old, careworn, and even ugly face, throws it with a few inspired touches upon his canvas, and it becomes, not only a palpable reality, but a spiritual fact.31

Fig.4

Luke Fildes

The Doctor c.1891

Tate

Photography © Tate

Fig.5

George Frederic Watts

Hope 1886

Tate

Photography © Tate

These paradoxical expressions – palpable reality and spiritual fact – are evocative of a phrase Oscar Wilde used in 1889 to describe the work of the writer Honoré de Balzac, ‘imaginative reality’, a phrase Rothenstein adapted in turn to define the temperament of Goya: ‘an imagination for reality’.32 They suggest that Rembrandt was perceived as something of a cross between the realist and the symbolist: an artist whose visual compromises were at the service of a greater human ideal – to uncover reality itself.33 In Rembrandt lay the key to what Rothenstein would refer to as life’s ‘hidden forces’ or ‘eternal verities’.34 In this sense, he was the perfect model for an artist at the turn of the century, trying on the one hand to escape the intricate, cluttered realism of artists such as Luke Fildes (see, for instance, The Doctor exhibited 1891, Tate N01522; fig.4) and on the other the rich and hazy symbolism of George Frederic Watts (see Hope 1886, Tate N01640; fig.5) or Edward Burne-Jones.

Rembrandt pointed the way to a constructive middle-ground, in which the formal qualities of a painting became more important, but not yet at the total expense of a realist narrative. The simplification of form was not pursued in and of itself, but in the service of a higher reality. Paintings were still ‘about’ something – it was simply less clear what the subject was, beyond that of ‘the poetry of human life and human endeavour’ (a phrase later used by J.B. Manson to describe the central theme of Rothenstein’s work).35 The trick – which Rembrandt was perceived to have pulled off again and again – was to represent everyday life in such a way as to represent humanity in general. As Rothenstein would write of his later interiors: ‘I was painting wife and child, and wished to suggest every-wife and every-child’, a passage that is reminiscent of the French critic Champfleury’s comments on Gustave Courbet’s famous painting The Burial at Ornans 1849–50 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris) as being ‘the representation of a burial in a small town, which nonetheless stands for burials in all towns’.36 The downside of the approach was that it demanded a lot from the viewer: what if they didn’t see every-child in the specific child? This thorny question lingers behind comments Max Beerbohm made concerning Rothenstein’s art in 1926: ‘Even if he be painting a barn or a tree, a cart or a hedgerow, [Rothenstein] seems to be saying: “What is this object? Just what part does it play among the eternal verities? And just how can I best pluck the heart out of it?” I cannot pretend to answer such questions.’37 Later criticism has shown less reluctance to shy away from the issue, with Ysanne Holt suggesting that old master allusions in the art of Rothenstein and his friends serve to obfuscate the social realities of the period: that by claiming to pursue reality, they were in fact leading their viewers down a blind art historical alley.38 The Rembrandt-like mood of The Doll’s House could therefore be seen as a means of legitimising potentially disturbing subject matter or making it more palatable to a collector.

Rothenstein’s pursuit of ‘reality’ was certainly a complex one, which would lead him, in time, to look beyond Rembrandt and into the world of Indian art, where the difference between ‘realism and reality’ was, he believed, much better understood.39 Along the way, however, it received much positive criticism, not least from Roger Fry, who wrote the following in 1910:

His work shows a fierce – an almost exasperatingly high – faith in reality. He is no realist, it is true, in the sense of one who thinks that art is a matter of mere representation; but he does think that not only must his inspiration be found in contemporary life, but that every particle of his expression of the idea must be forcibly distilled from the refractory material of the thing seen.40

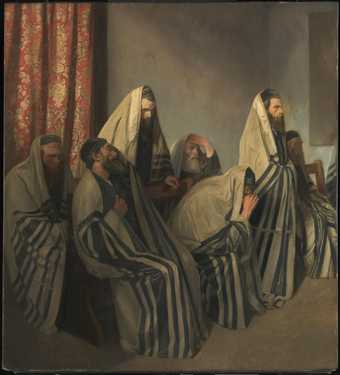

Fig.6

William Rothenstein

Jews Mourning in a Synagogue 1906

Tate

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

The same could have been written of Rembrandt. Indeed, the works to which Fry was probably referring in this passage – a series of paintings Rothenstein made of the Jewish East End of London between 1903 and 1908 – directly evoked the Dutch master. Although Rothenstein’s own Jewish identity and the political debates surrounding Jewish immigrants (culminating in The Aliens Act of 1905) form an important context for such works as Jews Mourning in a Synagogue 1906 (Tate N02116; fig.6), Rothenstein’s lingering interest in Rembrandt was crucial, as he himself admitted. ‘Here were subjects Rembrandt would have painted,’ he wrote, recalling his first visit to an East End synagogue, describing the ‘old gray-bearded men’ he saw there as having the ‘pathetic look of Rembrandt’s Rabbis’.41 It is as if it was the connection to Rembrandt and not the personal exploration of Jewish culture that provided the real spur to paint in Whitechapel. Finally Rothenstein had the opportunity to concentrate on images of old men: a subject he had long coveted and which he had always associated, again, with Rembrandt.42 Rothenstein was perhaps being wily here: he knew that his paintings would probably reach a wider audience if seen as Rembrandt-style studies of humanity as seen through praying Jews, rather than esoteric, quasi-documentary studies of a specific community in London.43 However, it is also a reminder of the extent to which the Dutch artist – whose influence was first felt, and self-consciously celebrated, in The Doll’s House – continued to steer the artist’s thoughts.