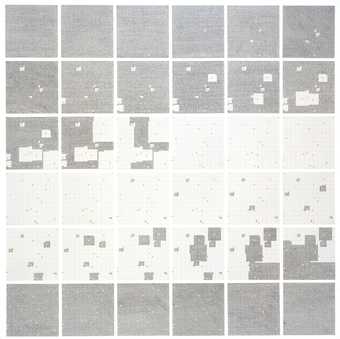

Fig.1

Jennifer Bartlett

Surface Substitution on 36 Plates 1972

Tate T06637

Jennifer Bartlett’s Surface Substitution on 36 Plates 1972 (Tate T06637; fig.1) comprises thirty-six one-foot (30 cm) square steel plates. The front of each plate is coated with white baked enamel, upon which a medium-grey grid has been silkscreened with mechanical precision. In each case the grid consists of one-inch (2.54 cm) squares marked with a thicker grey line; these modules are in turn subdivided into sixteen quarter-inch (0.6 cm) squares marked with a thinner grey line. The plates therefore each have a grid of 48 by 48 squares, which gives a total of 2304 squares per plate. Within many of the quarter-inch squares Bartlett has applied a single dot of enamel paint by hand, in black, red or yellow, while others are left blank.

The plates are designed to be read from left to right, as Bartlett explained in 1987: ‘Left is always one. Right is always two, three, four, five, six, even more than that. In the plates it was left to right, then you drop down and you go back to left. It’s like reading … the most straightforward way of doing it for a Western culture.’1 On the upper left plate, each of the 2304 squares in the grid is filled with a single black dot. Moving from left to right across the rows of plates comprising Surface Substitution, red and yellow dots are introduced with increasing frequency, the black dots become less frequent, and some areas of the grid are left blank. Most squares are empty in the centre portion of the composition. As the eye progresses further along the plates they begin to fill up again, and the grid on the final plate, in the lower right corner, is completely populated with black dots. Like frames of a filmstrip or panels of a comic, the sequential plates of Surface Substitution relay an idea in thirty-six parts.

Fig.2

Jennifer Bartlett

Artist’s notes on Surface Substitution on 36 Plates

Tate Conservation file

© Jennifer Bartlett

At first look Bartlett’s placement of black, red and yellow dots within the graph paper-style grid might seem random. However, the location and number of dots was generated using the Fibonacci sequence, in which each number is determined by the sum of the preceding two, and by the numerical series that this sequence produces.2 A sheet of graph paper containing Bartlett’s notes and signed by the artist accompanies Surface Substitution (fig.2); Tate acquired this with the painted steel plates in 1992. The graph paper ‘key’ decodes the content of the plates, naming and explaining the organising device – the Fibonacci series. This key suggests the central importance of concepts and ideas to the formation of Bartlett’s plate works, and she often included such brief descriptions of the generative schemes behind her plate pieces in the lists of works that accompanied her exhibitions in the 1970s.3 One part of the key for Surface Substitution reads:

Plate # 1 All black point

2 -1 red dot 26/46

3 1, 2 29/47

4 1, 2, 3 30/24

5 1, 2, 3, 5 23/24

As Bartlett jotted on the graph paper key: ‘Black surface [disappears] thru point selection fibonacci series #’ and, finally, is ‘reconstructed’.4 Hence the operation of Surface Substitution is reflected in its title: the work enacts the substitution of a surface from the first to the last plates, with iterative stages represented on the intermediate plates. The painting subtracts and reconstitutes its primary ‘image’ – 2304 squares each filled with a dot of black enamel – according to points indicated by the Fibonacci series.

‘Hard paper’

The thirty-six plates that comprise Surface Substitution are made of sixteen-gauge steel, which has a thickness of 0.0598 inches (1.52 mm), creating minimal volume when the plates are hung flush with the wall. Bartlett has referred to the plates as ‘hard paper’; they require no frame or stretcher.5 They are exceptionally portable since they can easily be packed in boxes for shipping and storage. Small holes perforate each corner of every plate so that thin carpenter nails can be used in mounting the plates to the wall. This was a variation on the ‘pushpin art’ of the period: ‘everyone put their art on the wall with pushpins, no frames, no glass. Many featured graph paper’, Bartlett has recounted.6 She allows for a one-inch interval between the plates when they are installed, giving compositional prominence to the wall itself, which becomes a linear, usually white grid around the plates. The white enamel of the plates is visually integrated with the white wall, while differing in tone and finish; the wall is not negative space so much as a component of the work itself.

When installed Surface Substitution forms a 1925 mm square, exceeding the height and lateral reach of most human bodies. The tens of thousands of diminutive, hand-painted dots across the thirty-six plates create a dramatic telescoping of scale. Each dot, contained in its gridded square, draws attention to details that are nearly imperceptible to the naked eye. The bristles of Bartlett’s 2.4 mm round sable brush have raked the liquid enamel paint into a subtle whorl that reveals the white surface beneath. Each dot is a unique and miniature record of the artist’s touch – painterly marks, however tiny, that contrast with the mechanised grids of both the silkscreened graph paper and the machined steel plates. As Bartlett commented in 2011, ‘you could organize anything with a grid … a pile of vomit, whatever, you could organize it’.7 The grid was pervasive in art of the mid-1960s, from the hand-drawn grids of Agnes Martin to the use of graph paper for drawings that was seen in the work of innumerable artists including Eva Hesse.8 Bartlett’s plates reference the grid’s prevalence on both canvas and paper, while possessing very different qualities of surface and functionality. As the artist noted, her plates were ‘hard grid paper that was impervious’ to the coffee rings and dust and grime of studio life. It was a surface ‘that you could wipe down and clean off every day if you were so inclined’.9

Ownership and acquisition

According to the date on the graph paper key that accompanies the plates of Surface Substitution, Bartlett made the piece in March 1972, the month following her first solo exhibition in a commercial gallery, held at Reese Palley in New York. Records suggest that prominent British architect Max Gordon acquired Surface Substitution from the dealer Paula Cooper, who had begun representing Bartlett in 1973.10 Gordon was known for designing exhibition spaces in major museums and galleries, and was well connected in the New York art world; he was a member of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art in the 1970s and a close associate of Cooper and many artists, including Richard Serra and Jasper Johns, whose living spaces he designed. (In the 1980s Gordon designed two flats for Bartlett, one in Paris and another in New York.) Gordon’s interest in Bartlett’s work in the 1970s therefore suggests her growing prominence within an influential circle of collectors, dealers and artists.

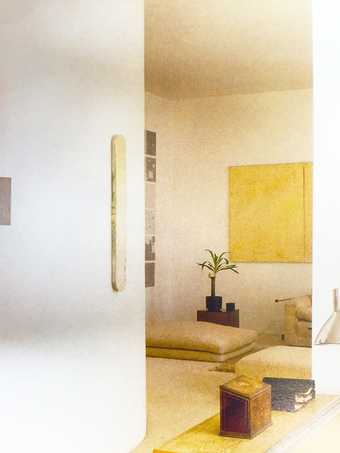

Fig.3

Interior view of Max Gordon’s flat at 120 Mount Street, Mayfair, London, c.1980, with a section of Surface Substitution on 36 Plates seen hanging on the far wall

Unidentified photographer

© reserved

It is not clear when or even if Surface Substitution was exhibited prior to its acquisition by Gordon, but it is known that once he had purchased the work he installed it in his London flat at 120 Mount Street, Mayfair. It appears in a photograph of Gordon’s living area from around 1980, a strip of its rightmost plates visible beyond a curved wall (fig.3). A beeswax and pigment relief by Lynda Benglis from the early 1970s hangs in the foreground, and Stephen Buckley’s Fresh End 1971 (Tate T06465), a four-panel work of rope-sewn canvas covered in primer and resin, appears on the adjacent wall to that on which Surface Substitution hangs. Following Gordon’s death in 1990, his family donated both Surface Substitution on 36 Plates and Fresh End to Tate in his memory. As Fresh End is described in a Tate condition report, written with Buckley’s input: ‘Studio dirt, including hairs and Gauloise cigarette ash have … been encapsulated in the resin. The resin was intentionally selected by the artist for its pinkish tint to create a flesh colour in appearance.’11 The photograph of Surface Substitution in Gordon’s home allows an in situ glimpse of the dialogue between Bartlett and the contemporary painting milieu to which Gordon was attuned. Works by Benglis and Buckley represent experimental approaches to painting that, like Bartlett’s methods, pushed the limits of the medium and introduced concerns about the body, site, temporality and process.

Specifically, Surface Substitution reflects the questioning of and scepticism toward painting that was prevalent in the New York art world of the 1970s. Conceptual art, minimal art, land art, process art and installation were dominant forms of American artistic practice in the late 1960s and 1970s. Such artists rejected the image and even the object of art, as well as its history, in favour of a focus on context: the environment in which an artwork was encountered and the social, economic and political situation from which it emerged. While painting was central to pop art from the 1960s onwards, pop artists such as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein mechanised their processes through silkscreen printing, stencils and the outsourcing of labour, in order to draw parallels between their paintings and mass-produced consumer goods, from comic books to Campbell’s soup cans. As is shown in the following discussion of Bartlett’s education and career, her plate pieces of the 1970s summarise, contest and expand upon such dominant artistic strategies. They are mechanistic, factory-made modules, but are also experiential, embodied proposals: handmade ‘systems’ in which abstract thought is communicated autographically and laboriously.

Artistic education

Bartlett was raised in Long Beach, California, a small city at the heart of an industrial region to the south of Los Angeles that prospered during and after the Second World War. Born in 1941, Bartlett belongs to a generation whose outlook was shaped by the post-war environment. As American industry flourished and the economy boomed, cold war anxiety bred conformity and consensus, to which the Beat artists and poets responded with expressions of social alienation, from Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl (1956) to Robert Frank’s 1958 series of photographs The Americans. Racial segregation persisted; Bartlett’s experience in Long Beach was ‘insular’, according to her recollection. ‘There were no blacks. There were two Jews’ and ‘very, very few poor kids’ who attended her high school. Bartlett recalled being drawn to the racial and economic diversity of surrounding communities and having boyfriends at other schools.12

The artist attended Mills College in Oakland, California, from 1960 to 1963. It was, in critic Calvin Tomkins’s characterisation, ‘“the Vassar [College] of the West”, a place for young women of the best families’.13 Bartlett established a serious focus on art at Mills. The art programme was vibrant and oriented toward painting, with a distinguished faculty during and after the war that included Fernand Léger, Max Beckmann and Clyfford Still.14 She became immersed in abstract expressionism and emulated Arshile Gorky in her painting. Bartlett formed a lifelong friendship with the painter Elizabeth Murray, a fellow Mills student. As she recalled to Murray in a 2005 interview, she pursued ‘Anything that had nothing to do with Long Beach, California … At Mills I picked up [the 1942 novel] L’Etranger by Camus, and my course was determined: art had to be dark, spare and serious’.15

In 1963 Bartlett left Mills for the Yale School of Art, where she earned a BFA in 1964 and an MFA in 1965. As Murray recalled to Bartlett in the 2005 interview, ‘The next time I saw you, you were a different person … this teenybopper girl in a miniskirt, a little Beatles hat tilted on your head’.16 Bartlett left the conformism of Long Beach behind as the 1960s progressed. Yet the suburban way of life of her 1950s childhood – the sunny idealism of Southern California’s burgeoning middle class – was exactly the lifestyle that fascinated pop artists in the 1960s. Of her time at Yale, Bartlett singled out pop artists James Rosenquist and Jim Dine as visiting instructors who made a particular impact.17 Pop sensibilities are intrinsic to her plate pieces, which employ the commercial enamels and the cold rolled steel used to make domestic appliances, along with a deliberately residual painterly association that recalls the importance of the hand – the artist’s autographic touch – for figures like Gorky.18 As such, Bartlett’s plates are nuanced reflections on twentieth-century painting, while also entrenched in the ideas of the minimal, conceptual and process art movements that took hold in New York after Bartlett left Yale in 1965.

Towards conceptual painting

The Yale School of Art offered what was arguably the most significant American studio art programme of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Bartlett lists Richard Serra, Brice Marden, Nancy Graves, Jonathan Borofsky, Silvia Plimack Mangold, Robert Mangold and Joel Shapiro among those who were her classmates or were recent graduates still involved in the programme as instructors while she matriculated. As Bartlett recalled, ‘Yale was such a community. All ambition, all the time.’19 It was an intense environment, with many major figures from the New York art world passing through as visiting artists. Bartlett took Josef Albers’s influential experimental colour class and studied painting with Jack Tworkov and Bernard Chaet. Tworkov, an advocate of pop even though his own painting style was rooted in abstract expressionism, become a lasting friend and supporter of Bartlett until his death in 1982. In addition to Rosenquist and Dine, Tworkov brought Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, Alex Katz and Al Held to Yale as visitors, figures whose approaches to painting and sculpture represent the varied expressions of pop in New York in the early 1960s.

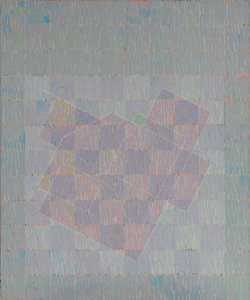

Fig.4

Josef Albers

Study for Homage to the Square: Departing in Yellow 1964

Tate T00783

© The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn and DACS, London, 2017

Beyond the prevalence of pop at Yale during Bartlett’s studies, is hard to overstate the lasting influence of Albers’s methods, within both the generation of students who worked with him at Yale and within the New York art world more broadly, where pivotal figures including Sol LeWitt absorbed his writings on process and colour. Artists as diverse as Rauschenberg and LeWitt credited Albers’s emphasis on hands-on experimentation and economy of means, through found colour and existing forms, as critical to the formation of their art practices. Form was largely predetermined in Albers’s paintings of nested squares, such as his Study for Homage to the Square: Departing in Yellow 1964 (fig.4). As critic Hilton Kramer summarised his approach:

Albers’s method is designed to remove the act of painting as far as possible from the hazards of personal touch, and thus to place its whole expressive energy – or as much as can survive the astringencies of the method – at the disposal of a pictorial conception already fully arrived at before a single application of pigment is made to the surface.20

Albers’s approach to painting as a conceptual medium helped LeWitt, for instance, develop a system-based approach in his own work, which progressed from painting to structures (see, for instance, LeWitt’s Wall Structure Blue 1962, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, and Floor Structure 1963, Museum of Modern Art, New York). Embracing predetermined forms and unmixed commercial paints was an implicit rejection of what LeWitt referred to as the ‘expectation of an emotional kick’ with which many viewers, critics and historians seemed to approach expressionist painting.21 Albers’s broader impact was seen in the adoption by artists of Bartlett’s generation of his belief that the viewer’s perceptual experience of form and colour was the root of painting’s significance, over and above painting’s status as a record of the artist’s subjective expression.

Bartlett started her studies at Yale the year that Albers’s famous book Interaction of Color (1963) was released. He was teaching there part time as a professor emeritus when Bartlett enrolled in his colour class. Albers’s pedagogical technique involved rapidly executed collages made using coloured paper, or free studies (collages of found materials, such as leaves), which Bartlett preferred.22 He promoted the use of found materials for ease and simplicity, and discouraged students from focusing too intently on academic methods. Mixing paint was ‘difficult, time consuming, and tiring’, Albers maintained in both his teaching and writing.23 Instead, paint taken straight from the tube was ideal, particular for the study of colour, and this approach was adopted by many painters of the period, including Held and Mangold. Albers himself used unmixed acrylic and oil paints for his long-running series Homage to the Square (see, for instance, Homage to the Square: Study for Nocturne 1951, Tate T12215), to focus on the effects of colour rather than the subjective or emotional judgments of the painter.

In 1968 Bartlett chose to restrict herself to Testors enamel paints that came in twenty-five colours. She started with just four colours – yellow, red, blue and green, along with black and white – but by the mid-1970s she was using the entire Testors palette for her plate pieces. This pre-set palette, along with predetermined forms or patterns such as dots placed according to the Fibonacci series, was chosen by Bartlett hand in hand with her turn to steel plates in 1968, which was also a matter of economising: ‘I thought that if I could just eliminate everything I hated doing, like stretching canvas, then I’d be able to work a lot more’.24 Bartlett’s attitude was influenced by the conceptual approaches to art that were circulating in 1968, particularly LeWitt’s expression of process laid forth in his influential 1967 essay ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art’: ‘In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair’.25 With Testors enamels and steel plates, Bartlett streamlined the painting process, which became further systematised through the adoption of mathematical schema in works like Surface Substitution. In Bartlett’s words, ‘if you make everything standardized … the content of the work would change’.26 What, then, was the new content of an artwork? This question became a sort of riddle in the practice of conceptual art.

Fig.5

Jack Tworkov

Knight Series OC#1 (Q3-75-#2) 1975

Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland

© Jack Tworkov/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Bartlett and Jack Tworkov had a joint exhibition in 1973 at the Jacob’s Ladder Gallery in Washington, D.C. Two years later Tworkov described his approach to painting in terms of the paradox between the control of numeric systems and the idea of accident or chance (see, for instance, his Knight Series OC#1 (Q3-75-#2) 1975; fig.5), stating that:

It is a very strange thing that I am on the one hand very much interested in some kind of geometric order or number system but on the other hand I am also very much interested in incorporating certain random, almost accidental qualities into a picture, or I would say non-intellectual – something I cannot control.27

Tworkov credited Bartlett for introducing him to the use of Fibonacci numbers. The tensions between a system and accident or chance – that which the artist cannot control (or does not seek to control) – was a guiding principle for Bartlett, too; systems were the subject of her paintings, such as Surface Substitution, although not the content. This was an important distinction for Bartlett, and is discussed further elsewhere in this In Focus in relation to her artistic process.28

From canvas to steel

Bartlett taught at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, from 1965 to 1967 and moved to New York in 1968. As she described her work in the years between leaving Yale in 1965 and adopting metal plates as her exclusive support in 1968: ‘I had been painting on canvas huge paintings, ten feet by thirty feet, and I spent almost all of my time making these stretchers … it was my most macho period, in which I felt like I had to build everything myself’.29 She agonised about what to paint, and later recalled a frustrating process in which she would present forty or so drawings to artist friends for opinions on which was ‘best’.30 A large oil painting was a major commitment: a single composition would become the focus of weeks of work. Yet Bartlett never felt invested in the content of the compositions she was painting.31

The decision to paint on the plates was based on a list of ‘negatives’ recounted by Bartlett in a 1978 documentary in which she was interviewed at length about her painting process:

I never wanted to have to decide one thing for sure again in painting. I never wanted to build a stretcher. I never wanted to sew canvas again to make it big enough for the stretchers I would build. I never wanted to unstretch a canvas to get it out of a space or doorway that was much too small to accommodate it. I didn’t want to stand up anymore when I painted because basically I just like to lie down. I wanted to work on a small unit that would be flexible that you could make an enormous surface out of.32

When she adopted the steel plates, Bartlett committed herself to painting on this support for a five-year period as ‘a way of making a space of five years to work’, regardless of the critical reception.33 It was a matter of economising the painting process, to allow a new approach to content to emerge through a radical method that discarded the conventions of painting that had previously defined her practice.

Bartlett’s decision to work on steel plates turned out to be a definitive move. Her five-year commitment was key: Bartlett’s consistent use of a distinctive, easily recognisable format allowed her to gain critical recognition and establish a market among collectors for her plate pieces by the early 1970s. By this time, she was gaining a reputation within the New York art scene. Her first exhibition of plate pieces was in 1970 in the Soho loft of her friend and neighbour, the artist Alan Saret, who hosted informal shows by artists whose work interested him. Saret was closely identified with process art, and the repetitive ‘dotting’ technique that Bartlett had established was, by 1970, in dialogue with new conceptions of drawing and mark making practiced by Saret and others.34 In 1972 she exhibited plate works at the Reese Palley Gallery, and in 1974 had a show at Paula Cooper Gallery. These solo exhibitions at important galleries furthered Bartlett’s reputation as a serious artist, attracting the attention of collectors like Max Gordon.

After Surface Substitution

Fig.6

Jennifer Bartlett

Rhapsody 1975–6, detail

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Cooper would remain Bartlett’s primary New York dealer through to the 1990s, hosting numerous solo exhibitions as well as readings by Bartlett of her autobiography History of the Universe, begun in the late 1960s and published in 1985. Bartlett’s Rhapsody (fig.6), her 1975–6 magnum opus comprising 987 one-foot square enamelled steel plates, was exhibited at Cooper’s Soho gallery in 1976. It was scaled to fill the entire space, moving definitively into the realm of installation art. Rhapsody is an icon of postmodernist pastiche, combining dozens of painting styles and referencing multiple historic and contemporary genres, from abstract painting to kitsch advertising images. It received widespread attention for its scale and ambition, making Bartlett ‘an instant celeb in the New York art world’, in the words of critic Grace Glueck.35

Fig.7

Jennifer Bartlett

At Sea Japan 1980

Woodcut and screenprint on paper

571 x 2545 mm

Tate T07443

After Rhapsody Bartlett experimented freely with medium and style. Swimmers Atlanta 1979, a large-scale public commission for the Atlanta Courthouse, combined oil on canvas with enamelled steel plates. She also worked expansively with drawing and printing techniques, including woodcuts, such as At Sea Japan 1980 (fig.7), in which an impressionist and quasi-abstract aquatic theme is extended across six frames. Bartlett began living in Paris part time in 1983 with her second husband, the actor Mathieu Carrière. She had gained an international reputation after Rhapsody, and a Paris base allowed a broader perspective on the neo-expressionist style of painting that was dominant in both New York and continental Europe in the 1980s. Her paintings began to involve sculptural components that expanded painted images into real space, as can be seen in works such as Sunset and Concrete Dock 1984 (fig.8). Nonetheless, the plates persisted in her work. As she observed in 2006: ‘I work on these plates I kind of invented 30 years ago, and they keep coming in and out of my work’.36 Bartlett continued to make works involving ‘epic systems’, such as Rhapsody: Song 2007 (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland), a grey-scale abstract sequence spanning 180 dotted steel plates, and Recitative 2009–10 (private collection), which employs coloured dots on 372 plates installed in column formations on multiple walls. Bartlett’s more recent work includes oil paintings on canvas that are responses to a hospital stay: diaristic, rapidly painted glimpses of hallways and out of windows, rendered in large scale for her series Hospital 2015.37

Fig.8

Jennifer Bartlett

Sunset and Concrete Dock 1984

Oil on canvas, painted wood, concrete slabs

Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland

While Bartlett’s work from the 1970s onward has been ambitious, her vacillations with regard to style and medium have problematised her reception, as has her status as a woman artist whose work refuses easy associations with her gender (as her friend and fellow artist Joe Zucker noted in a 2005 interview, ‘Jennifer [Bartlett] wanted to make art that had no gender’).38 What were Bartlett’s artistic investments, particularly in relation to her mathematically based compositions of the early 1970s? What ideas did she seek to develop through an approach to art that managed to simultaneously occupy the terrains of conceptual, painterly, pop, minimal, systemic and process-based painting and installation practices? Rather than assuming a secondary position for Bartlett among the dominant figures of such trends (a common hierarchy based on gender or market success), this In Focus places Surface Substitution on 36 Plates at the centre of discourses on these ideas and movements.

Surface Substitution on 36 Plates falls within an early but critically formative stage of Bartlett’s wide-ranging career in installation-based painting, in which she experimented with and synthesised many of the concerns about painting that preoccupied artists at the time. The choice of support, paint and process used for Surface Substitution, as well as its modular format and use of the wall itself as a frame, are aligned with a critical questioning of the medium of painting that coincided with a period of social upheaval in the United States, from the women’s movement to the Vietnam War (1955–75). As curator Kynaston McShine wrote in the 1970 catalogue for the exhibition Information held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York: ‘It may seem too inappropriate, if not absurd, to get up in the morning, walk into a room, and apply dabs of paint from a little tube to a square of canvas. What can you as a young artist do that seems relevant and meaningful?’39 For Bartlett, the choice to paint was a highly self-aware act. Her materials and process allude both subtly and broadly to mass culture, the history of painting and to conceptual and embodied, durational approaches to art. With Surface Substitution, Bartlett was making painting relevant and meaningful within the complex concerns of her milieu.