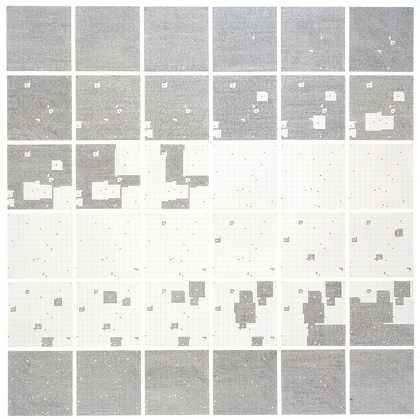

Fig.1

Jennifer Bartlett

Surface Substitution on 36 Plates 1972

Tate T06637

Jennifer Bartlett’s time at the Yale School of Art from 1963 to 1965 gave her a close awareness of the ideas and strategies of major trends in contemporary art, particularly the tensions between modernist abstraction – the abstract expressionist approaches that had dominated the New York scene throughout the 1950s – and pop art, which was dominant by the mid-1960s. Pop artists Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Jim Dine, Roy Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist were visiting artists during Bartlett’s years at Yale. In interviews she has acknowledged the significance of each of these major figures as she developed directions for her own painting practice in the mid- to late 1960s, singling out Rosenquist’s impact ‘In terms of really actively putting to use a kind of vocabulary in my work’.1 The enamelled steel plates and enamel paints that Bartlett used to make Surface Substitution on 36 Plates 1972 (Tate T06637; fig.1) are arguably a direct reference to American post-war consumerism, and this section will make the case for the relevance and importance of pop art for Bartlett, in particular the influence of street and subway signage and mass-produced appliances that populated the American home.

Fig.2

James Rosenquist

F-111 1964–5

Installation view

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© James Rosenquist

Fig.3

James Rosenquist

Capillary Action II 1963

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

© James Rosenquist

Rosenquist’s F-111 1964–5 (fig.2), a painting with 23 sections that stretches to over 26 metres in width, lined three walls of the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York in 1965. It depicts a to-scale fighter-bomber aeroplane montaged with images of American mass consumerism: a Firestone tyre, a tangle of orange Franco-American canned spaghetti, and a young blonde girl under a salon hairdryer that also looks like a missile or a helmet. It is an epic commentary on the military–industrial complex – the interdependent relationship of the spending power of the American middle class and the defence industry, with its insatiable demand for new war machines. Rosenquist combined oil on canvas with aluminium panels to communicate both the gleaming surface of the bomber and the shine of consumer objects. As Bartlett recalled in 1987, his paintings ‘were big … at the Greene Gallery where he got canvas on the wall and then there’d be a kind of dead tree standing in front of it and then something with a light. He had a very cool sensibility that was erratic.’2 She was referring to the assemblage Capillary Action II 1963 (fig.3), for which Rosenquist positioned a small dead tree in front of a framed plastic sheet that hung on the wall like a canvas, the surface of which was streaked with capillary rivulets of red, yellow and blue oil paint. The immersive scale and theatricality of Rosenquist’s work in the 1960s transcended painting to become installation. This is a strategy Bartlett seem to have emulated, filling the walls of galleries with hundreds of plates in her first New York exhibitions of the early 1970s, and later with works like Rhapsody 1975–6 (Museum of Modern Art, New York). The plate pieces, installed collectively, were huge in scale; they went around corners and formed backdrops for readings of her poems and autobiography in the early 1970s.

As Bartlett noted, ‘I liked James Rosenquist’s idea of an impersonal style’.3 The imagery of Bartlett’s plate works from the late 1960s and early 1970s was devoid of the overt political commentary of Rosenquist’s paintings: her early plates depicted mathematical formulae or utilised graphics such as maps or the simplified motif of a house. Yet Bartlett was similarly intent on approaching painting as a distanced, non-emotive recording process that registered the contemporary world. Rosenquist’s ‘impersonal’ painting style that Bartlett admired related to his background as commercial painter of signs and billboards, and her plate works shared the status of public signage: in seeking a new support in place of canvas, she noticed the enamelled steel plates used for New York subway signs that ‘looked like hard paper’, and chose to make her paintings on this material.4

As with Rosenquist and other pop artists, Bartlett’s plate works are objectively readable paintings, containing information that can be widely understood. Yet if the signifier, whether Fibonacci series or house, is transparently obvious, like the directive on a subway sign, the meaning or content of a plate piece as an object is unresolved. How the viewer understands the significance of works such as Bartlett’s Surface Substitution on 36 Plates, taking into account the materials, installation and the experience of ‘reading’ the plates and their arrangements, is left wide open.

An industrial aesthetic

When Bartlett chose her new support in 1968, she took a loan from a friend, the artist Joel Shapiro, and commissioned a batch of around one hundred enamelled ‘cold rolled’ steel plates from P. Feiner and Sons, a manufacturer in New Jersey.5 According to Bartlett, the company ‘made the plates with deburred edges and sub-contracted the enamel surfaces to someone who did home appliances’.6 Cold rolled steel is an industrial fabrication process that produces a smooth, dent-resistant surface for consumer goods. When enamelled, it is commonly used for home appliances (from food mixers to washing machines), bathroom fixtures or signage, among myriad commercial and industrial applications. In Bartlett’s words, the baked enamel surface of these plates was ‘like a refrigerator’.7 This choice of a fixed, industrially fabricated unit was common among minimalist artists such as Carl Andre, Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt in the late 1960s.

Bartlett’s choice relates as much to the influence of pop as to minimalism – both movements that commented on American industry and consumerism by utilising uniform repetition and evoking the standardisation of the built environment and objects within it.8 Bartlett’s plates are diverted from familiar consumer and public usage, and exist in her work as fragments of those things – the signs, bathtubs or refrigerators that fulfil a function in modern industrialised society. While Bartlett’s plates are not images of refrigerators, they operate metonymically, as parts suggesting a whole. The same point applies to Bartlett’s decision to use Testors enamel paints in her work. Adopting the enamelled steel plates meant abandoning oil paint, and Bartlett opted for the vibrant, unmixed commercial hues of craft enamels not commonly associated with fine art, but primarily used by hobbyists to paint models, ornaments and toys.

Bartlett’s highly specific and repeated use of the same materials – enamelled steel plates and Testors enamel paint – gives clues to the significance of works such as Surface Substitution: their logic and content. In Bartlett’s analogy, ‘Each painting has a particular kind of logic … If you were writing music, I wouldn’t use a bassoon to communicate the same information as I would a triangle.’9 The plates and enamel paints in Surface Substitution therefore contain ideas and meanings relating to their ubiquity in mass culture and their centrality to American consumerism, yet without insisting on a specific message or meaning that would undermine the work’s simultaneous abstraction.